In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void: and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, let there be light and there was light.

No, I haven’t gone all religious. But as a metaphor for knowledge over dark ignorance, for intellectual enlightenment over a lack of curiosity, for the development of language out of silence, you can’t beat this old quote from Genesis. It also symbolizes the spirit of Liliane Lijn’s eclectic work which, for more than forty years, has explored our phenomenological relationship with the world we inhabit and our sense of being and becoming. From the microcosmic to the macrocosmic, from the human body to the physical properties of light, she investigates, through her far-reaching visual language, what it means to be sentient and alive.

- Liliane Lijn, Get Rid of Government Time, 1962 © the artist

I first came across her work more than twenty years ago when I was writing for Time Out and discovered her kinetic Poem Machines (1962-8) that pioneered the use of rotating poetic texts, initially cut from newspapers and Letraset. I can’t remember, now, where I first saw them. Simply the sense of excitement that I felt as a young female poet discovering a woman artist working at the intersection of the visual arts and language, myth and philosophy and the hitherto largely male world of technology and science. Since then I’ve got to know her and her diverse body of work. The early expressive paintings and explorations of the body, the kinetic sculptures and projects that involve complex physics, often undertaken in collaboration with top scientists.

Today I’ve come to her large elegant studio in north London. It’s a lovely space. Full of books and sculptures and, this afternoon, flooded with balmy late September light. Her assistant works away quietly in a far corner, filing and doing essential paperwork, while we talk. Well-read and with a wide-ranging intellect, Liliane Lijn was born in the US in 1939, four months after her mother and grandmother, of Russian Jewish descent, arrived from Antwerp.

“My feelings about science—in particular the physics of light and matter—are that they are pure poetry”

Her parents’ early divorce lead to school in Switzerland where she became fluent in both French and Italian, leading her to study archaeology at the Sorbonne and art history at the École du Louvre. But these academic subjects were soon given up in order to pursue the life of an artist. In Paris she met André Breton, the French poet and surrealist, and later, back in early sixties New York

, she moved in the same hip circles as beat poets such as William Burroughs and Gregory Corso.

She has, she says, always been interested in language and writing but that changing languages from English to Italian interrupted the flow somewhat. This, she suggests, might be why she chose to express herself primarily visually. Though she sees the disciplines of writing, visual art and science as permeable. Moving between them creates a dialogue, a way of asking questions and investigating the world. “My feelings about science—in particular the physics of light

and matter—are that they are pure poetry,” she tells me.

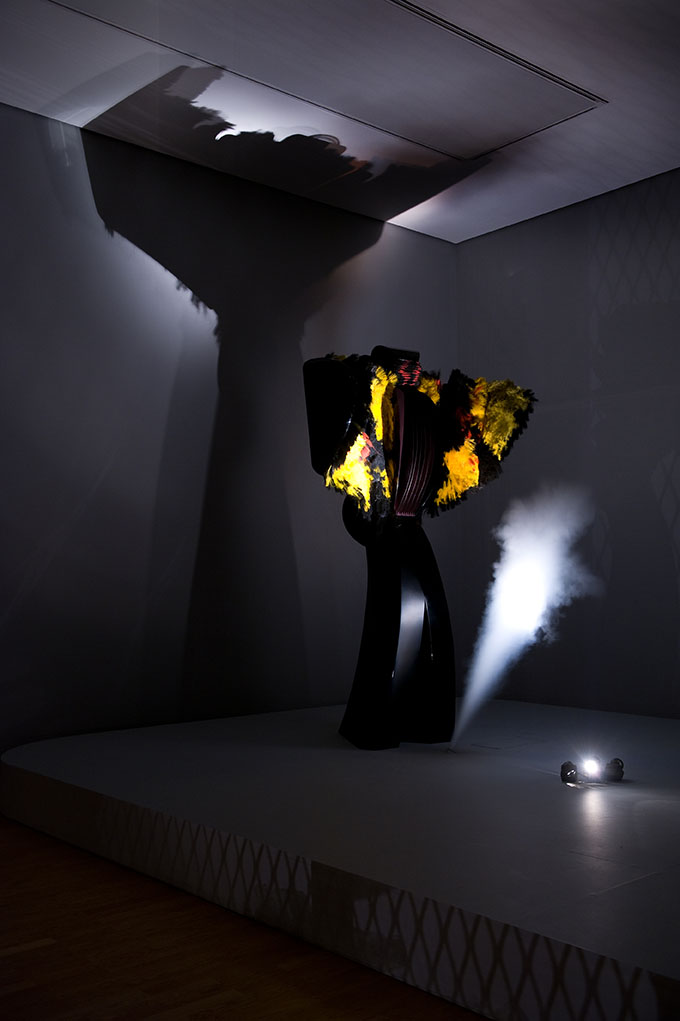

As we sit in the autumn sun at a glass table held up by legs made from her multi-coloured cones, she describes her work as “a constant dialogue between opposites. My sculptures use light and motion to transform themselves from solid to void, opaque to transparent, formal to organic.” She’s just come back from Athens, she tells me, where she’s been installing Cosmic Dramas at Rodeo Gallery. It’s an interesting and timely revisiting of her early work. The bold choreography of the Conjunctions of the Opposites: The Woman of War (1985) and The Lady of Wild Things (1983)—two looming kinetic “figures” that stand more than three meters high and use LED light, smoke, lasers and brushes—touch on ancient ideas of the female goddess, though constructed with modern industrial materials. Although made at different times, she doesn’t think of them as set in opposition.

They are, she explains, neither male nor female, but cosmogenic gods. Hermaphrodites that are bisexual in nature and through whom we experience the strongest and most striking opposites. When set side by side they create a seductive psychic drama. “They’re spiritual archetypes. Powerful, angry sexual pieces. The Woman of War sings a bold, audacious song. A song, that when I wrote it, seemed to come into my mouth straight from the earth. The idea came to me when I was a young student in Paris and living on the sixth floor in an empty apartment which I was using as a studio. Standing on the balcony one evening I had a vision. The sky was lit by an extraordinary sunset and I saw the image of a goddess in the clouds. Woman of War grew from an attempt to reconstruct that experience.”

I ask if she thinks feminism has changed since the works were made, at a time when women were looking for new narrative models to describe their lives. Did she think that they could be easily understood by the #MeToo generation? Populism, she says, concerns her. There’s a sense of dumbing down. A need to jump on bandwagons. She feels people are afraid of complexity and ambiguity. But, she adds, it was interesting that so many of those who came to the opening in Athens were young. “They were excited. They seemed to get it. And it wasn’t just young women but also men.”

Anyway, she insists, she was never a typical feminist. What interested her was the intellectual pursuit of subjects seen as predominantly male. Her work in the late 1970s to the 1990s was largely based around the body and feminine archetypes: The Wife, The Medusa, The Lady as Bird, The Darkness. But then there was a pivotal moment when she decided to stop making art that was autobiographical and expressive, to move outside and dematerialize the body. That’s when she began working with light. Her approach to the use of light is, she suggests, less architectural, less mechanistic than that of many male artists. For her light is liquid and has an almost anthropomorphic quality.

This summer she’s been busy working on Sunstar, a large-scale daytime “spectroheliostat” art installation sited on the top of the historic 150-Foot Solar Tower on Mount Wilson in Pasadena. The work is a collaboration with the astrophysicist John Vallerga. A beam of diffracted sunlight is projected onto the Los Angeles

landscape, making the solar spectrum visible at specific locations. “The spectrum is broken down. It creates a single incredibly bright point of light. It’s very small, very brilliant like a star or a jewel that can be seen in the day.

“What interests me is scientific discovery. What it means to be alive, to live in this world”

Normally we can’t really look at the sun. But this allows us to look at a tiny fragment of it. Would she have liked to study physics? “No, I don’t think so. I like what I am. I have a lot of freedom. But I’ve read up about it over the years. You can only get to the kernel of things through physics and chemistry.” They help her, she continues, explore the issues that really interest her such as: what is essence, what is something’s essential character. “I’m not really interested in finance or politics. That’s all such a mess, anyway, and there’s little as individuals that we can do to influence them. What interests me is scientific discovery. What it means to be alive, to live in this world.”

Recently she was commissioned by Leeds University

to create a nine-metre high revolving drum of transforming words, Converse Column, which will be sited next to the university’s new design centre, Nexus, that opens this autumn. Words and phrases were suggested by students around the concepts of knowledge and interconnection. These were then cut up so that the text and light used becomes fluid in these spinning drums. The aim is to create a work that provokes questions and encourages debate. She was inspired by the concept of Nexus. “So much of my work is about just that: connections relation, conjunction, invention and research.”

As we talk I can detect no signs that Liliane Lijn is slowing down in her eighth decade. There’s a youthful, restless intellectual hunger about her that continues to spur her on to make original eclectic work—work that challenges the very paradigms of what constitutes art.