When news went viral about Michael Jackson’s sudden death on 25 June, 2009, there had been such a pile-up of outlandish press stories throughout his existence, that I’d initially assumed that the “scoop” was some sick internet hoax. The next day, glimpsing newspaper headlines as I walked to my office, I was startled to find myself crying. Jackson’s music had always been in my life, but I don’t think I’d fully realized until then how attached I felt, or how epic, emotive and tragic his whole legacy was. Too late—yet somehow more vital than ever.

Michael Jackson was always something else: more than an astoundingly prodigious talent, more than Peter Pan or the King of Pop, more than a vilified demon, more than a cultural muse. Nobody looked, sounded or danced exactly like him, although generations of people around the world obviously tried to. If MJ appeared hyper-real in his lifetime, then he represents something stratospheric in an age where we use “iconic” to describe a five-second GIF of Britney Spears flicking her hair. And he yields genuinely rich material for On the Wall: the National Portrait Gallery’s new exhibition of artworks inspired by MJ, which apparently took around a decade to develop.

“If MJ appeared hyper-real in his lifetime, then he represents something stratospheric in an age where we use ‘iconic’ to describe a five-second GIF of Britney Spears flicking her hair”

There have been numerous tributes to MJ in recent years, and these have generally felt pretty hollow, whether it’s touring stage shows like Thriller or Cirque du Soleil’s One, or the ghostly collection of costumes and scenery posthumously presented at London’s O2 Arena (where he was due to begin his extensive This Is It live residency in July 2009). On the Wall is an exceptionally rare thrill, from the instant you walk in and see a Keith Haring painting of MJ that hasn’t been on show for thirty years. It doesn’t attempt to summon his spirit through mimicry or memorabilia; it brings everything vividly to life through the artists’ personal experiences and interpretations.

“Michael Jackson is the most depicted cultural figure of the twentieth century,” says assistant curator Lucy Dahlsen. “His impact is really an untold story, and what’s amazing about this exhibition is that it features ninety works from more than forty-five artists, in a huge range of media. Many of these artists grew up in the seventies, eighties and nineties, so he was the soundtrack to their lives.”

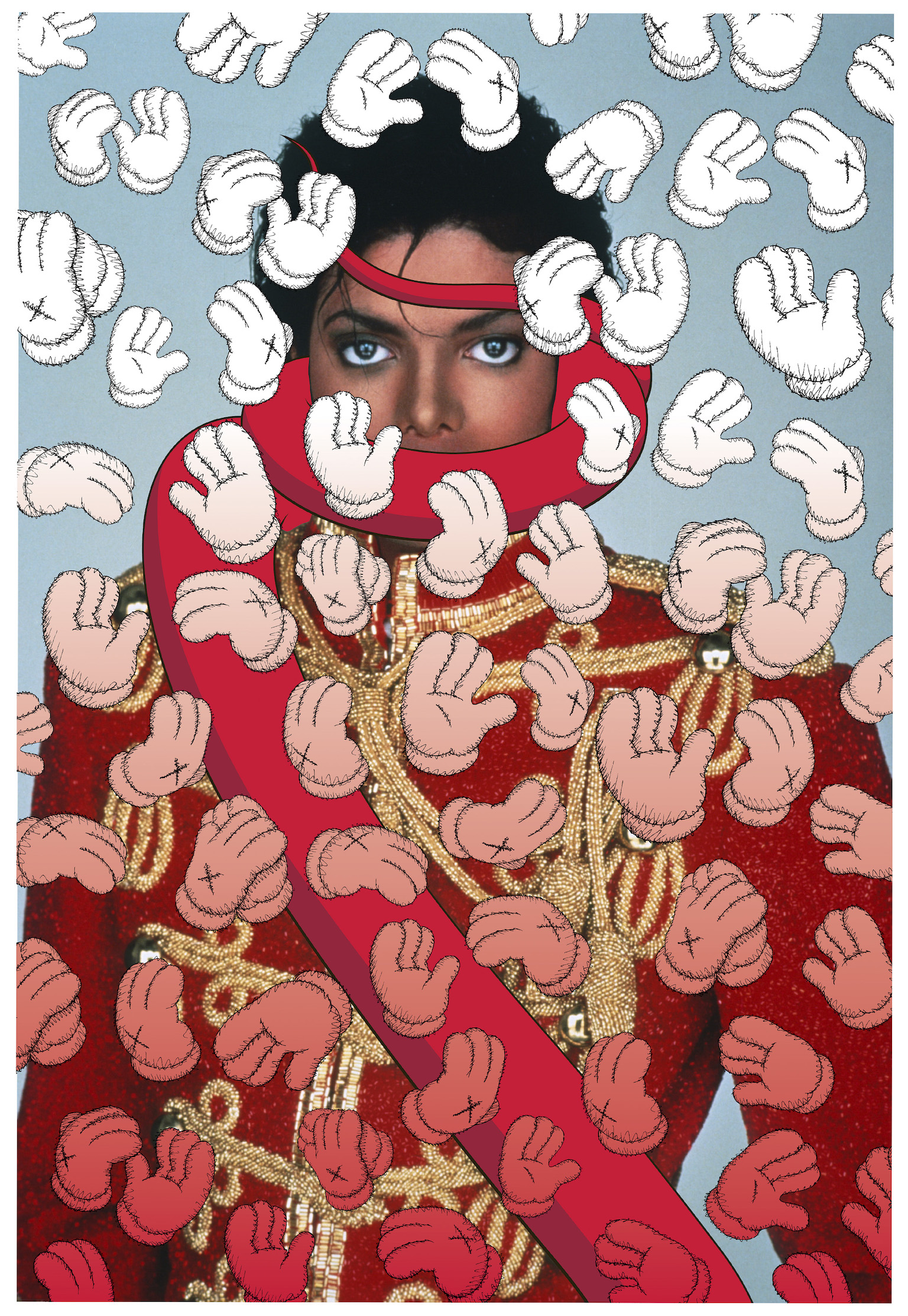

Many of On the Wall’s works illustrate how immediately recognizable MJ remains, even in manipulated portraits or silhouette (Dara Birnbaum’s 1987 images The Way You Make Me Feel are based on Polaroids taken of MJ’s MTV clips); it just takes a pair of shoes on pointed toe; a tilted hat; a bejewelled glove; a squeal; a zombie lurch or a funky thrust, and we know exactly who this is. Sometimes, it’s simply his piercing eyes, stripped of their shape-shifting surroundings in Jordan Wolfson’s Neverland (2001)—this video is taken from Jackson’s 1993 denial of the child abuse allegations instigated by Jordan Chandler’s father. On the Wall is at different turns unsettling, poignant, funny and revelatory; crucially, it never feels like a hagiography.

“We are trying to be objective,” says Dahlsen. “A lot of the works are celebratory; others consider the more difficult sides of what Jackson represented. It’s more an exploration of what he meant.”

The global scale of what MJ meant still seems extraordinary; to label him an “international brand” negates the degree of genuine human connection here. In Todd Gray’s Cosmic Speakers (2015), the LA-born, West Africa-based artist took photographs of MJ to a remote Ghanaian village and created layered images of his subjects. “Everyone in Ghana claimed this star as theirs, as African,” says Gray.

I found myself thinking of the MJ devotees I’ve encountered in everyday life around the world, from rural Lancashire to coastal Italy, and also of Amr Salama’s 2017 Egyptian comedy-drama Sheikh Jackson, which depicts a young man torn between religious dogma and pop devotion. Back at the NPG, the exhibit reflects how MJ has resonated across black American artists to white working-class queer youth (in Dawn Mellor’s teen sketches) and way beyond.

MJ gave few media interviews in his life—hardly surprising, given the endless grotesque tabloid splashes he endured; one Brit newspaper clipping, taken from Isaac Julien’s 1984 collage The Other Look, slavers over MJ’s childhood traumas, before continuing: “Tomorrow: I’m not gay”. Elsewhere, I recall a disappointingly bland feature in early-eighties pop magazine Smash Hits, which contrasts sharply with his incisive, witty soundbites displayed at the NPG, whether he’s quoting Michaelangelo, reflecting on human nature or discussing Rubens’s brushworks with Kehinde Wiley, whose 2010 Equestrian Portrait of King Philip II (Michael Jackson) looms majestically over the main hall. Beyoncé and Jay-Z may now strike a stylish pose at the Louvre (and there’s no denying that Bey packs a cross-cultural punch), but these megastars linger in MJ’s shadow.

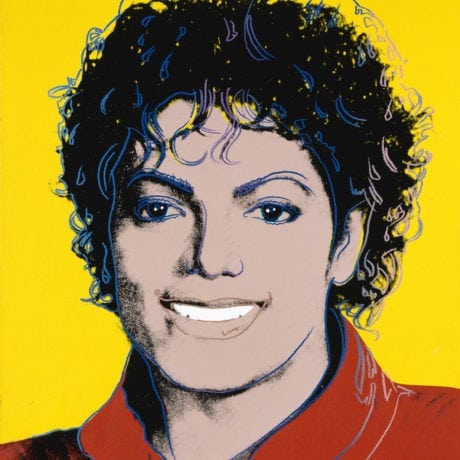

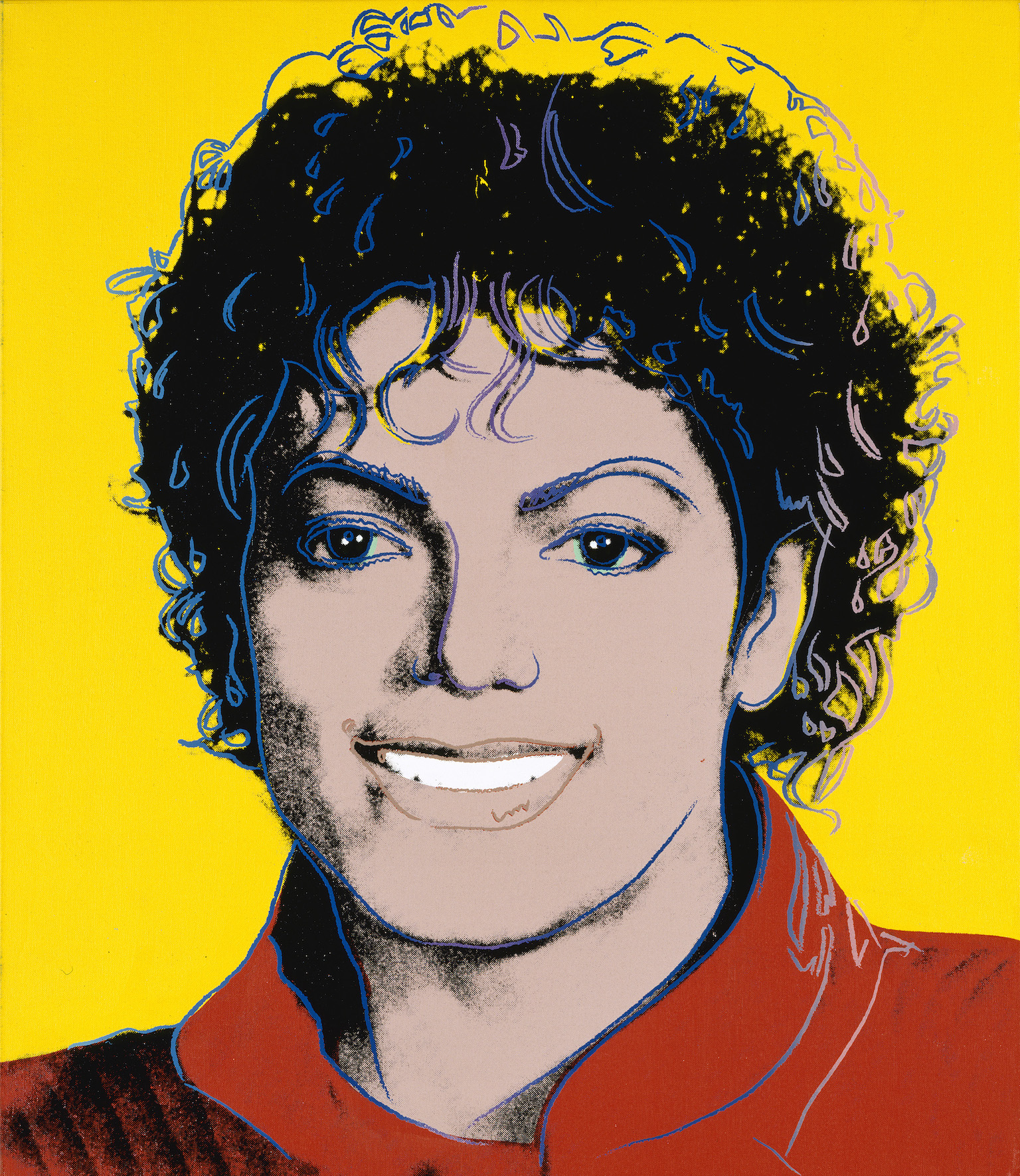

There are some choice souvenirs amid the formal artworks in On the Wall. These include an avant-garde dinner jacket designed by MJ, adorned with dainty cutlery (“because it’s the one thing that every man, woman and child in the world knows”, he explained). In the King of Pop Art room, Warhol’s legendary 1984 silkscreen portraits of MJ are accompanied by his own “time capsule” collections— here, the “Superstar of the eighties” appears as a poseable doll in “Grammys” attire, marked down to $2.99.

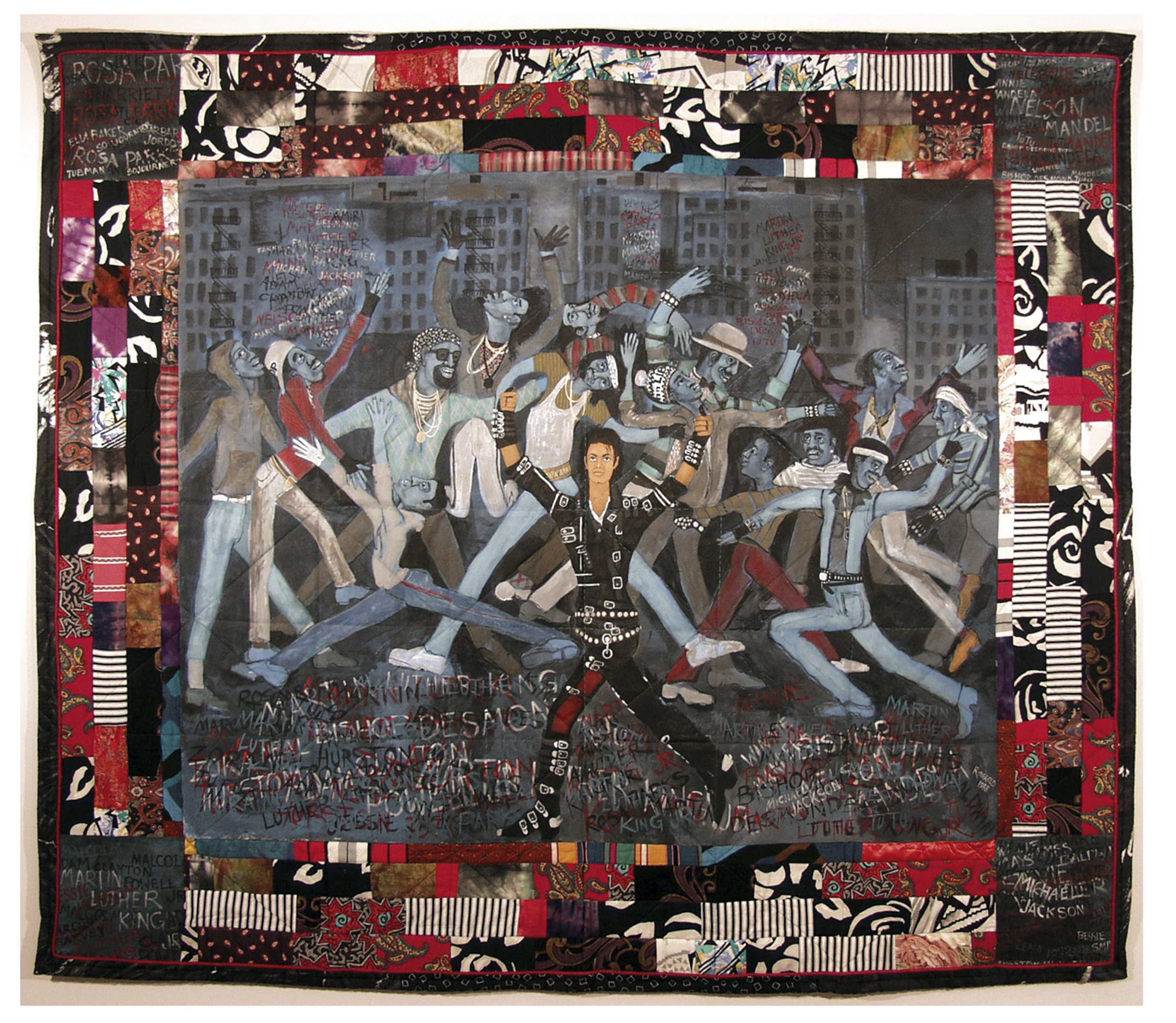

When I originally became a music journalist in mid-1990s London, “Wacko Jacko” was a widely derided figure, lambasted for his bombast (a 30ft statue of the King of Pop, designed by Diana Walczak, was sailed down the Thames to promote his 1995 HIStory album), shunned for his scandals and ridiculed for his optimism. He was also often slated as a traitor to his race, and there are intriguing shades of this variety at NPG; David LaChapelle’s 2009 triptych American Jesus portrays the pale-skinned, surgery-sculpted legend in messiah mode, while Lyle Ashton Harris’s oil painting Black Ebony II (2010) memorializes him on vintage Ashanti funeral fabric. Collectively, these disparate perspectives actually transcend conflict, and form an unusual unity: melding stardust fantasy, heartfelt empathy and reality. The credit given to MJ by civil rights activists also demands attention here, whether it’s an eloquent (and prescient) quote from James Baldwin, or Faith Ringgold’s beautiful painted quilt, Who’s Bad? (1988), displayed for the first time here, and depicting MJ alongside Mandela, Rosa Parks, Tutu, MLK. At MJ’s funeral, Queen Latifah read a poem specially composed by Maya Angelou, beginning: “Beloveds, now we know that we know nothing, now that our bright and shining star can slip away from our fingertips like a puff of summer wind.”

Every room in On the Wall holds fascination, though I found myself most haunted by a Rolling Stone magazine from 1971, featuring an eleven-year-old MJ as its youngest-ever cover star. His side-eye expression evokes a multitude of things: intelligence, sensitivity, beauty, potential, wariness… and his talent and torment now feel liberated across endless lifetimes.

Arwa Haider’s On the Wall Playlist for Elephant

A disclaimer from Arwa: Surely you’d need at least one hundred songs to create an “essential” MJ playlist, considering the King of Pop’s vast solo catalogue, his childhood sibling group The Jackson 5, his soundtrack work and other riches. So this is no way a definitive playlist—but it aims to accompany the NPG’s On the Wall artworks, and to offer a soundbite of the fantastically varied soundworlds that MJ created…

- Off the Wall

The title track from MJ’s sublime 1979 album (co-produced with Quincy Jones) never loses its spirit-soaring vitality. The NPG’s On the Wall exhibition draws from this theme, and also reflects the music’s visuals (and the spirit of fandom) in Graham Dolphin’s 2017 artworks, arranging MJ’s classic record sleeves with meticulously handwritten lyrics. - Workin’ Day and Night

This irrepressibly funky number is also taken from Off The Wall. In DC-based artist Susan Smith-Pinelo’s video installation Sometimes (2000), multiple screens display a close-up of the artist’s bosom, as she shimmies to this track; the effect is hypnotic, funny, fierce—and makes you want to dance, too. - Ease on down the Road #1 (with Diana Ross)

A giddy-sounding young MJ (as Scarecrow) and Ross (as Dorothy) duet on this feel-good groove from The Wiz soundtrack: a 1978 film adaptation of The Wizard Of Oz, featuring an all-black cast, songs by Charlie Smalls and production by Jones. The hit musical led to MJ’s first coverage in Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine. - Honey Chile

MJ leads The Jackson 5’s cover of this Martha and the Vandellas soul track, taken from the sibling group’s 1971 album Maybe Tomorrow—in a year when MJ became Rolling Stone magazine’s youngest cover star. - The Way You Make Me Feel

This snappy 1987 pop/R&B smash hit proved influential both for its sound and visuals; in On the Wall, it also inspires shadow portraits of MJ by Dara Birnbaum. - Billie Jean

An unmistakeable 1983 intro, a groundbreaking (and sidewalk-illuminating) video—and part of the inspiration for David LaChapelle’s 2009 portraits of MJ, entitled American Jesus. - Thriller

The title track from the best-selling album in the world (1982), the ultimate Halloween theme—and the inspiration for several artworks in On the Wall, including a choral video installation from South African artist Candice Breitz. - Bad

The title track from MJ’s 1987 “comeback” album had a tough act to follow, but it still packed plenty of guts, and a refrain that inspired Harlem artist/activist Faith Ringgold’s beautiful embroidered portrait, Who’s Bad? - Black or White

This upbeat celebration of unity was the lead single from MJ’s 1991 album Dangerous, and boasted hi-tech, shape-shifting video portraits. Mark Ryden’s intricate painted artwork for Dangerous is also transformed into a vast walk-through gateway in On the Wall. - Stranger in Moscow

A 1995 anthem about intense isolation, reflecting the much darker moods (and personal experience) of MJ’s HIStory album and world tour. - Remember the Time

This slinky 1992 R&B pop groove (co-written with Teddy Riley) presented another cinematic video (this time, transporting MJ to ancient Egypt, with an all-black cast including Eddie Murphy and Iman). Michael Robinson’s These Hammers Don’t Hurt Us (2010) dreamily melds footage from this video with the 1963 film Cleopatra, uniting MJ with his close friend Liz Taylor. - Scream (with Janet Jackson)

This fabulously spiky 1995 duet with sister Janet was accompanied by reportedly the most expensive music video ever made ($7million), which features MJ browsing a digital gallery of art, from Magritte to Warhol. You can watch clips in On the Wall’s King Of Pop Art room. - We Are Here to Change the World

This 1986 number forms the climax of MJ’s ground-breaking 3D Disney film Captain EO (directed by Francis Ford Coppola): the musical legend becomes an otherworldly superhero. - Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough

This swirling 1979 disco odyssey was the first single that gave MJ full creative control—and it feels genuinely timeless. - I’ll Be There

On the Wall reflects the incredible range of creative impact that MJ’s legacy has achieved, and this 1970 boyhood number (with The Jackson 5) remains sweetly resonant: it’s beautiful enough to break your heart.