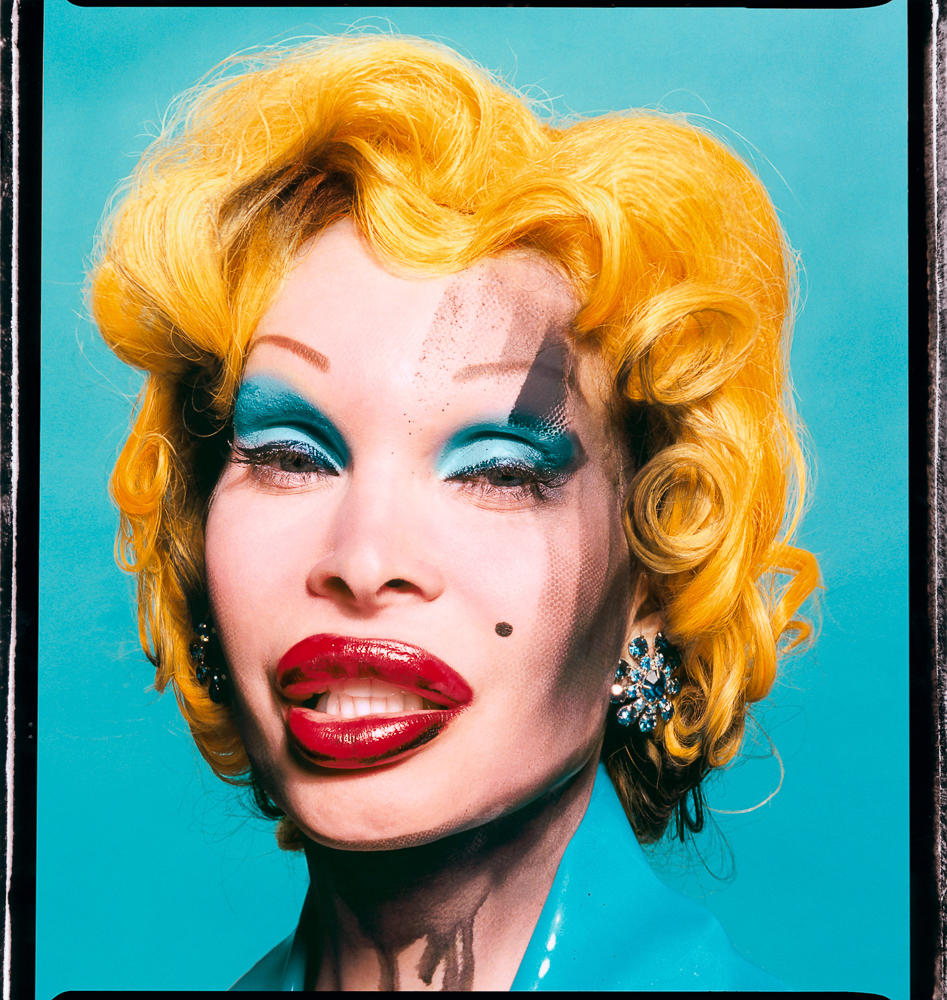

David LaChapelle understands the art of excess. The photographer’s resplendent images, ripe with saturated colour and a huge dose of high-concept camp, have seen Pamela Anderson emerging from a giant eggshell, Lil’ Kim’s body adorned with the Louis Vuitton logo, and Amanda Lepore reimagined as Andy Warhol’s screenprint of Marilyn Monroe. His shoots for Interview, Rolling Stone and The Face

set the tone for 1980s and 1990s abundance and are something of a touchstone for contemporary pop culture.

Yet LaChapelle is far more than a celebrity photographer. Through an adept fusion of glossy illusion and raw sensuality, he has created epic odes to history paintings, religious icons and even formal still lifes, all of which are on show at a major new exhibition at Fotografiska in New York.

“It’s like a group show,” LaChapelle jokes, over a sketchy line from Maui in Hawaii, where he has lived for over 15 years. “I’ve wanted to have a big exhibition in New York for ages. One that represents all the facets of my work. It is happening just a block from where my first show took place back in 1984, at what is now 303 Gallery. I convinced Lisa Spellman to turn her loft space into a gallery back when she worked in fashion, and now she’s a major dealer. It’s a full-circle moment.”

“I took jobs to pay for my fine-art practice and that was a blessing. Working under different conditions and pressure made me a better photographer”

This kind of hustle is characteristic of a man who turned truant at 16, running away from Connecticut to New York to immerse himself in the grit and grime of the city. While others might have dropped creative pursuits in favour or partying, he kept up an artistic portfolio that led to a fully paid spot at art school.

It was here that he discovered photography, though he’s keen to point out that the idea of the medium as an art form was still in its infancy. “People weren’t collecting photography in the 1980s, and if they were it certainly wasn’t mine,” he says. “Black and white was all anyone cared about: Bruce Weber, Herb Ritts and Robert Mapplethorpe.”

Nevertheless, LaChapelle was determined to make it work, traversing the accepted delineation between ‘fine’ and ‘commercial’ practice to pay the bills, and landing a job with Interview magazine when he was still a teenager, thanks to Andy Warhol. “I took a lot of shit for doing commercial work, but I didn’t have a sugar daddy: I didn’t want one!” he says. “I took jobs to pay for my fine-art practice and that was a blessing. Working under different conditions and pressure outside of my personal interests made me a better photographer.”

“Young audiences’ minds aren’t made up. They come to see Doja Cat or Dua Lipa, and might be introduced to something entirely different”

He explains that artists will always have money concerns if they want to make it on their own, which is important to remember when the grind gets you down. “There are letters from Diane Arbus begging magazine editors for jobs,” he says. “People are put on these pedestals, but they could be grovelling for $400. I feel very blessed that I’ve been able to work in the field that I love. I used to separate the two [commercial and personal] but now I see it all as part of a wider picture.”

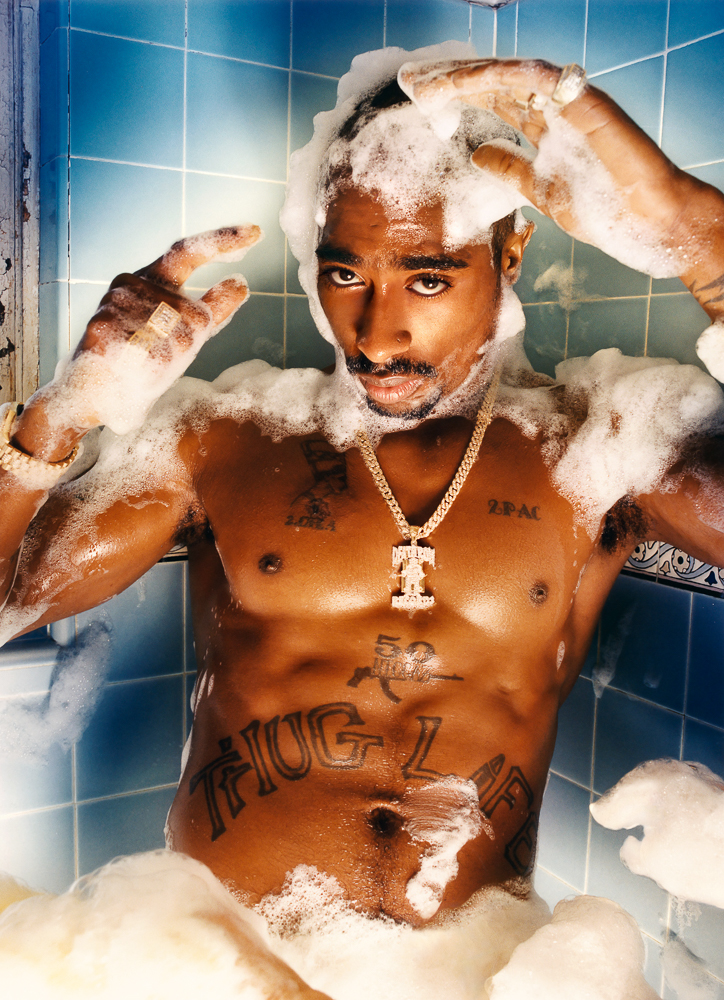

That fact is clear. While other slick fashion or portrait shoots might employ the same ambitious scene-building LaChapelle is known for, the results can often appear sterile and bloodless. Conversely, his images are always bursting with life. Each project is treated with the same dedication to a concept, whether it be an intimate snap of Tupac Shakur in the shower, a forensic reimagining of Georgia O’Keeffe paintings, or a post-modern iteration of Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus.

Tupac: Becoming Clean, 1996, Los Angeles

While his shots often include incredible assemblages, the process of creating them is a very calculated affair, although he always maintains a sense of spontaneity and humour. “I’m not a reportage photographer,” he says. “I go out and create tableaus, documenting what I create theatrically.”

“I never got into photography for the getting part, it was always for the giving. A photo is not finished until a viewer connects with it”

He is driven by a need for connection too. The idea of being a famous photographer who has shot some of the most recognisable names on the planet was never the end goal. “I always want to create pictures that will touch people,” he assures me. “I never got into photography for the getting part, it was always for the giving. A photo is not finished until a viewer connects with it.”

This mentality is clear in projects such as Angels, Saints and Martyrs (1984), where he painted directly onto negatives to create ethereal images that tried to visualise what the human soul might look like. It came out of a need for a purpose during the Aids crisis, when so many of LaChapelle’s friends were dying. “I was questioning what it meant to be alive, because I didn’t expect to be around very long,” he says.

Nowadays, he is delighted to see that his work resonates with a younger crowd, who might find him through shoots with contemporary stars via Instagram. “It’s really great to have a young audience because their minds aren’t made up.” He adds. “They might come to see Doja Cat or Dua Lipa and be introduced to something entirely different, because it’s not just the art world that I’m speaking to.”

“I’m not a reportage photographer. I go out and create tableaus, documenting what I create theatrically”

I tell him that his cross-generational appeal is something I am intimately familiar with. In my house growing up, my dad’s copy of the 1996 book LaChapelle Land was a prized possession. I was allowed to read it under careful supervision, where the photographer’s mastery of colour composition and staging was relayed to me, and made a lasting impression.

“I’ve often had people tell me that their son or daughter has a copy of my book, but this is the first time I’ve been told ‘my father’ has it!” he laughs. “Talk about perspective. I’ll take that.”

Holly Black is Elephant’s managing editor

David LaChapelle, Make Believe, is at Fotografiska, New York, until 8 January 2023

Images: © David LaChapelle. Courtesy Fotografiska New York