Of all the mediums, painting is perhaps the one that has most doggedly remained associated with tradition. Say “painting” to someone on the street, and it’s likely they’ll think of representational images—portraits, perhaps; still lifes; landscapes. Because it’s been around for so long, and because some of the world’s most widely recognised artworks (the Mona Lisa, for instance; or the Girl with a Pearl Earring) are painting, it’s easy to slip into seeing painting as a stylistic shorthand for the “traditional” in form and process. Especially in 2019, where we’re so used to things that move, speak, “perform” or even reflect our own faces back to us in sculptural shiny baubles; painting will (for the most part) always be resolutely static. It is passive, if you want it to be: there to be looked at, not played with, eschewing the already-tired “interactivity” that much art has strived for in the digital era.

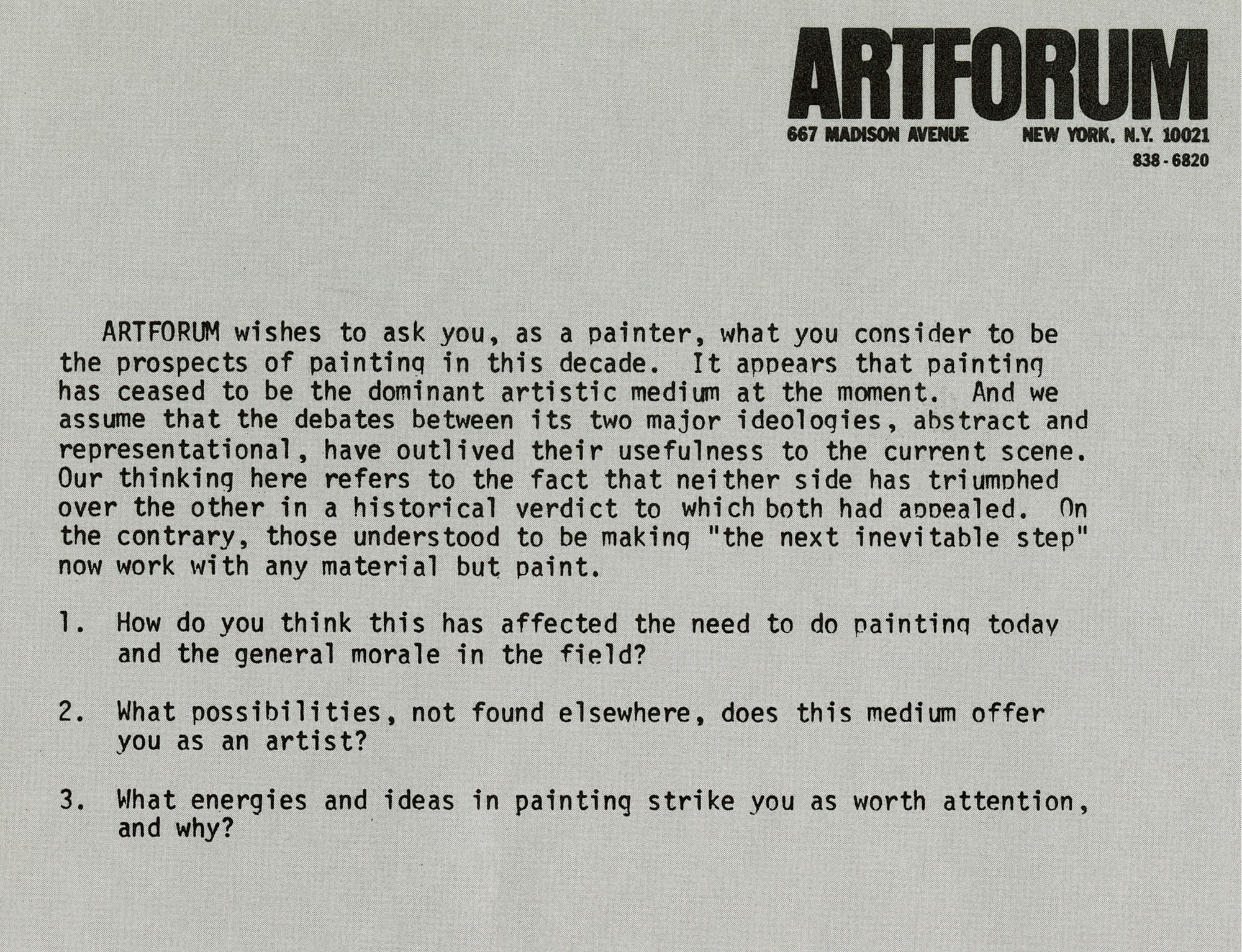

But does that mean painting can’t be exciting, radical? Not to mention, of course, that almost “dirty” word in art-appreciation—“beautiful”? Of course it doesn’t. In 1975, Artforum magazine published a plea in simple typewriter lettering that addressed painters directly, asking them what they “consider to be the prospects of painting in this decade”; one it said had seen it “cease to be the dominant artistic medium”. The ideologies of “abstract and representational”, it continued, had “outlived their usefulness”. What, it asked, was the next step? What possibilities can painting offer than no other medium can? Finally, it asked, “what energies and ideas in painting strike you as worth attention and why?”

They’re thought-provoking questions, when you consider painting then, and now. There’s certainly no suggestion whatsoever that “abstract and representational” have died a death—it could indeed be argued that we’re seeing more (great) representational work than ever, such as in the work of Sofia Mitsola, Nina Chanel Abney, and Chantal Joffe—albeit addressing themes that place them firmly in the now.

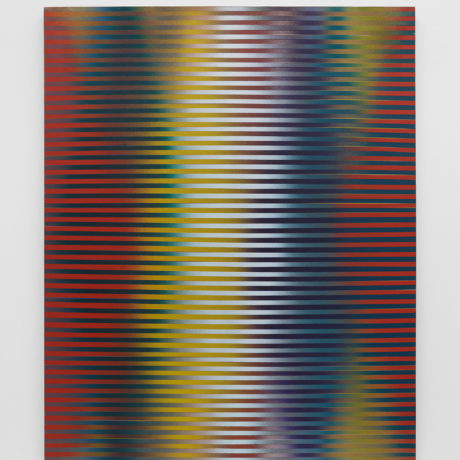

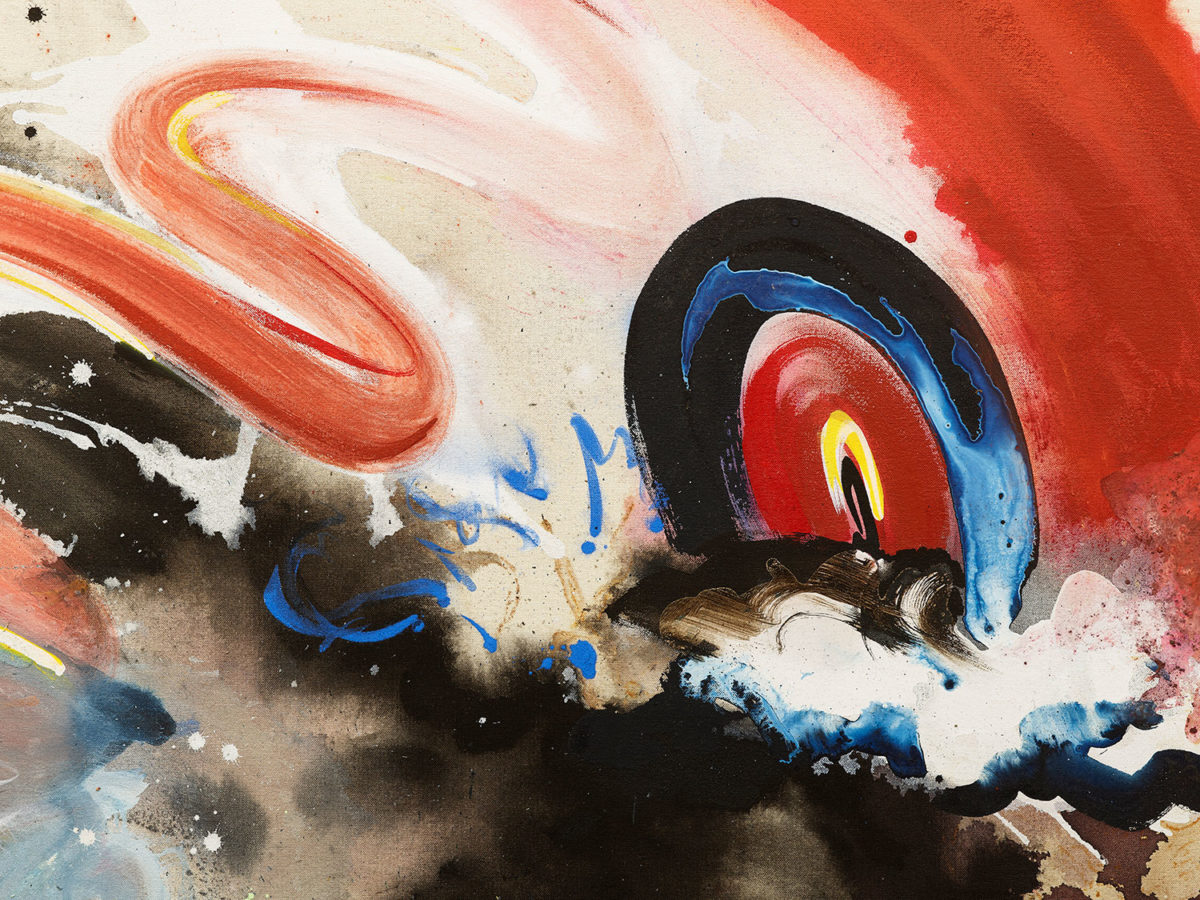

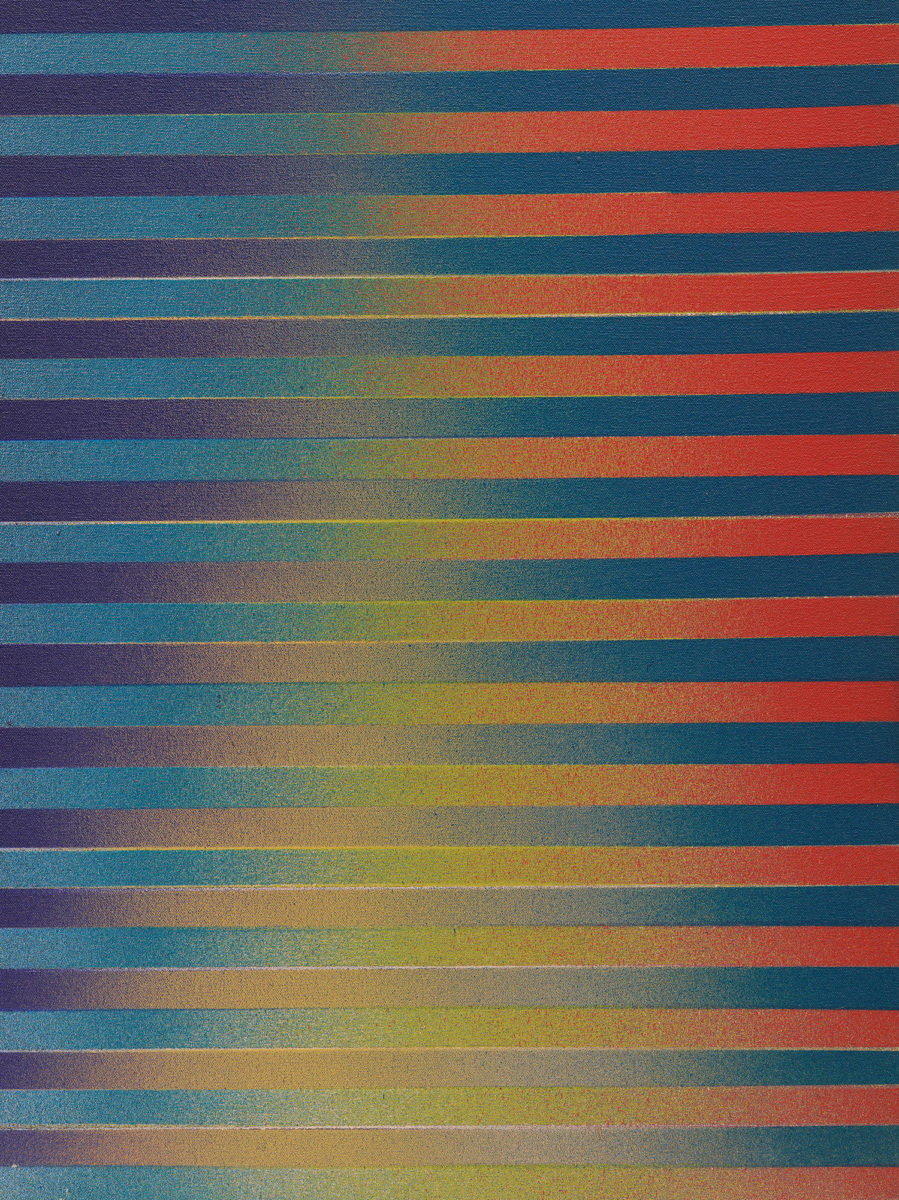

A current show, titled Painters Reply: Experimental Painting in the 1970s and Now at Lisson’s New York gallery, surmises that the Artforum “questionnaire” was less a provocation, and more “an obituary… an indictment of futility”; suggesting that emergent terms of the 1970s such as “Lyrical Abstraction” and “New Informalism” effectively stilted things, and “failed to capture the breadth and dynamism of the medium, leaving many to simply condemn it.” The Lisson show turns this obituary from a wake to a big, colourful, celebratory party; showcasing work that was being made that proved painting and painters were far from done.

“Painting has not just longevity, but boundless artistic freedom”

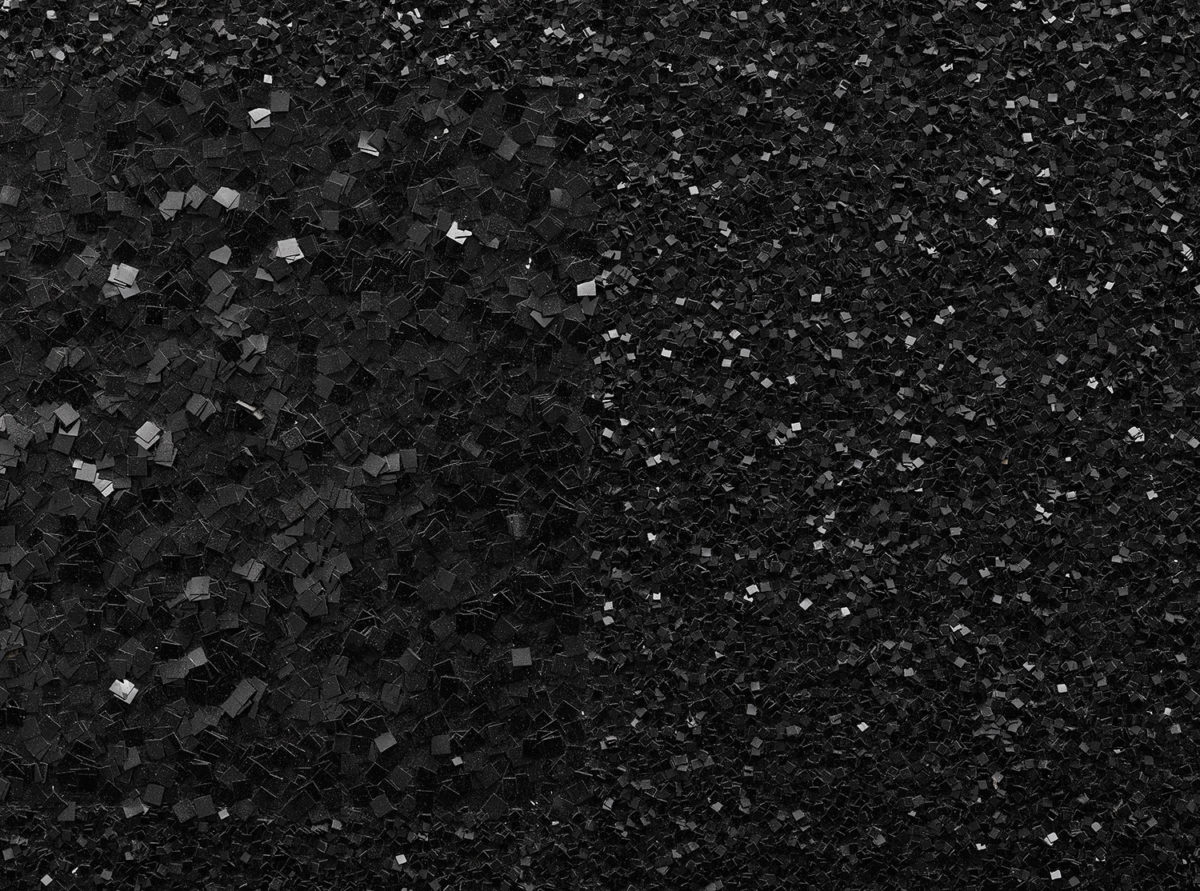

Things were, in fact, dynamic; and what’s interesting about the work that curators Alex Glauber and Alex Logsdail have selected to prove this are notable in the fact that they frequently shift painting from tubes, brushes and canvases into almost sculptural forms (such as in the glorious work of Lynda Benglis). Many of the works subtly draw from newer mediums, such as performance, in the way they were created: the impulses behind them are frequently playful, personal and dynamic; and many pieces look at how incorporating other materials (velvet, wood, metal and even quid ink make cameos); new modes of application; ways of adding dynamism to static pieces; and reconfiguring how painting is viewed and displayed mean the medium has not just longevity, but boundless artistic freedom.

The list of artists is refreshingly balanced in terms of gender, if not nationality. But what does it say about painting? We see a lot of it here at Elephant, and we’re certainly excited by it on a daily basis. So, thanks for the warning Artforum, but no need for another obituary just yet.

Painters Reply: Experimental Painting in the 1970s and Now

Until 9 August 2019 at Lisson Gallery, New York

VISIT WEBSITE