Satire has a long and complicated history, with writers using wit and parody to draw attention to cracks and flaws in society from Ancient Egypt all the way through to contemporary life—The Onion and Private Eye are prime examples. It’s integral to Thomas More’s Utopia; James Gillray and William Hogarth’s paintings and political cartoons; Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator and Stanley Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove; and TV shows including Spitting Image and Have I Got News for You. Unlike sarcasm, and its reputation for being the lowest form of humour, satire manages to criss-cross through society, aiming both high and low, and occasionally toppling those in power.

At the Ljubljana Biennial of Graphic Arts, curated by Slavs and Tatars—whose practice takes the form of exhibitions, books and lecture-performances, rooted in themes and ideas concerning “an area east of the former Berlin Wall and west of the Great Wall of China known as Eurasia”—the radical potential of satire today is being considered via a mix of works, from furniture and market stalls, through to magazine archives and itinerant voting booths. Now in it’s thirty-third edition, it has also provided an opportunity for Slavs and Tatars to consider the biennial’s heritage in graphic arts, and how that ties in with the history of satirical periodicals; the affordability of print and potential of distribution in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, and the increased access we have to hardware and software today.

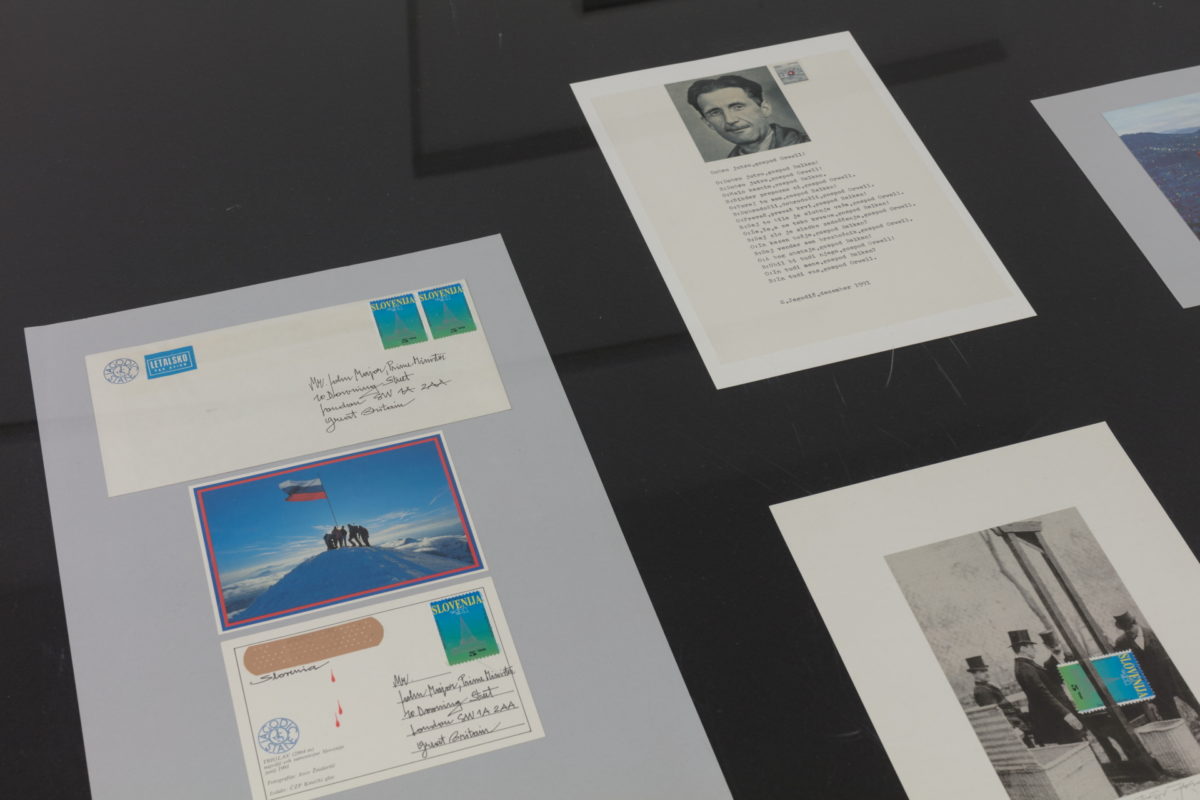

A selection of Slovenian satire periodicals from the International Centre of Graphic Arts’ (MGLC) archive are displayed among the exhibition, chronicling responses to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Kingdom and the Socialist Federation of Yugoslavia. The use of illustration and caricature in satire periodicals is effective in its potential to create archetypes and popular characters, in its immediacy in communication, and the fact it can cross language barriers—both as a sort-of visual Esperanto, and as a form of communication that could negate issues of literacy. Many of the publications are named after animals or plants known for being prickly, including Jež, or “hedgehog”; Kača, or “snake”; and Bodeča neža, or “silver thistle”; and Pavliha, the longest-running journal, had a repeat character, Martin Krpan, who was known for being a trickster, and has since become a sort of folk hero “drafted to bolster claims of self-determination”.

Another example of popular culture displayed as part of the biennial, is Top Lista Nadrealista, or “The Surrealists’ Top Chart”, a TV sketch comedy that aired in Sarajevo in the 1980s. For its first season Nadrealista focused on themes including Yugoslavia’s preparation for Euro 1984, lampooning Star Trek, and an ongoing parody of Romeo and Juliet that told the story of star-crossed lovers separated by a cross-town football rivalry. By its second season, which aired in the period leading up to the Yugoslav Wars, it dealt more directly with politics, thanks to the willingness of its network-assigned executive producer to trick his TV Sarajevo superiors by airing sketches that directly mocked those in power.

In line with the approach of Nadrealista, in their introduction to the biennial, Slavs and Tatars suggest that living in “sour times” requires “sweet-and-sour methods”. They frame satire as something that has the potential to “tease, stunt or terrorize”, and raise the question: “Is each joke, as George Orwell maintained, really a tiny revolution? Or do laughter and satire release the pressure that would otherwise lead to political upheaval?”

In America, TV shows such as Saturday Night Live and Veep, and commentators Samantha Bee and Stephen Colbert, among others, have gone from being enjoyed as light-hearted fun, to being considered as essential political devices. Political cartoons throughout the world are becoming ever more meaningful and potentially divisive, and as the news becomes increasingly absurd, The Onion somehow manages to stay ahead of the daily cycle—but could it be going further? Even when European and American politics seem to be hitting new heights of stupidity and new ethical lows, when writers, comedians and artists take shots at politicians, policy and the news of the day, the stakes are often low. Of contemporary, Western satire, Slavs and Tatars’ Payam Sharifi says: “Satire has the potential to be quite conservative, suggest[ing] it was better as it was before—a true progressive agenda would be bringing down those norms full stop,” he says. Considering the freedoms we enjoy, and the lack of real pressure or force on those who speak or act out against government, are we achieving the revolutionary potential of satire, or as Slavs and Tatars suggest, just “releasing pressure” that may otherwise create change.

In their selection of work for the biennial, Slavs and Tatars focus on practices that make use of the “slipperiness” of definitions, in terms of both context and meaning. A lot of the work sits between art and design, between so-called high and low culture, and rather than reflecting directly on present-day politics, offers ideas that could inform the future. They engaged with the history of the biennial, which is rooted in graphic arts, not through showing graphic design practice, or showing the work of graphic artists, but by considering the “democratic potential” of its heritage, and the ideas of satire and publishing as a form of “popular philosophy”. Showing work by historical and contemporary artists—including Fluxus artist Endre Tot, and contemporary artists Martine Gutierrez, Zhanna Kadyrova, Kriwet, Ella Kruglyanskaya and Lawrence Abu Hamdan—as well as interventions by activists, new media polemicists, scholars and stand-up comedians, what pulls it all together is a sense of humour “with a level of sophistication behind stupid or simple gestures, a thickness behind the facade”.

Uninterested in work “where the discourse is clearly available”, they focus on pieces that draw you in without giving everything away. Kriwet’s text signs, a series of circular, badge-like layouts of letters that “slip” between forming various words—including “YOUTHIRSTY”, “SUBURBANDIT” and “SODOMESTICK”—interrupt conventions of reading and the structures of language. Artist Dozie Kanu’s work sits somewhere between sculpture and furniture, bringing together what’s perceived as incompatible ideas, in regards to form and function, and the potential for objects to carry multi-layered narratives—of dreams of mobility, car parts, hip hop and the performance of blackness. In Martine Part I-IX, Martine Gutierrez explores the complexity, fluidity and nuances of both personal and collective identity in a video filmed in a variety of locations—including Providence, Central America and the Caribbean—which symbolize her character’s process of self-discovery, and how they negotiate various perceptions of gender identity. A trans, Latinx artist of indigenous descent, Gutierrez asserts control of her own image by taking control of the entire creative process, in a characteristically subversive look at how society seeks to control “unruly” bodies, and how deeply embedded sexism, racism, transphobia and other biases are within our culture.

One of the more direct engagements with the theme of satire is No More Fuchs Left to Give—a collaboration between book dealer Arthur Fournier and scholar Raphael Koenig. The installation of books, editions and periodicals considers the work of German book collector, art historian and Marxist activist Eduard Fuchs; who, through his publishing programme, was key to the development of ideas around the role of mechanically reproduced satirical images in the production of political discourses in the early twentieth century. In a great twist, prints from his out of copyright books are now available to buy from walmart.com, as “canvas wall art for your home or office”, and Fournier and Koenig ordered a few for the exhibition, which draws on Koenig’s recent work as a scholar in comparative literature at Harvard University. Aware of the potential for satire to both talk back to power and reinforce existing mechanisms of discrimination and oppression, Fuchs’s research and collection is a rich resource for clues about how we might grapple with authoritarianism, nationalism and neoliberalism today.

Of the value of satire, Sharifi suggested it’s in the balance of “sophisticated, deep research with stupid gestures”; “too often, people who do one, don’t take the risk of the other”. Artists engaging with satire often do so with the intention of taking on political and economic systems and tropes, but they also almost self-satirize, or parody the smaller world in which they move (as do films like The Square and Velvet Buzzsaw). Marcel Duchamp satirized the art establishment, Andrea Fraser’s institutional critique parodied museums and their various hierarchies, Elmgreen and Dragset satirize via theatrical installations, and Jeff Koons thinks he’s a satirist.

- The Square, 2018. Still. Courtesy of Curzon Artificial Eye

In Crack Up – Crack Down, the potential of humour—balancing sophistication with stupidity—and work that is “slippery” in regards to its implications, is presented with confidence; but the study of satire, from its roots in journals to the present day, has left Sharifi with mixed feelings about how we employ it. “As things become more common, they lose a certain power, and I think I’ve come to the conclusion that [satire] isn’t as effective as it was before,” he says. “But I still have a lot of hope. I believe that words are powerful—the way that stand-up comedy puts pressure on language, poetry, new terminologies for gender and sexuality. Language has a lot of power and always will; it’s a good antidote to the glut of visuals we’ve had recently.”