I have to tell you about my encounter with Powerless Structures, Fig. 11 [Elmgreen and Dragset’s diving board installation from 1997] at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark three years ago. My friend and I were monkeying around in the gallery and we climbed on to it without realizing that it was one of the displays, and we took lots of photographs of ourselves until security came and threatened to kick us out.

Ingar Dragset: That’s a great story, I love it. I hope you still have photographs of you guys!

Michael Elmgreen: Actually, the diving board installation is getting a second life now because we’ve created a new version of it (with a slightly different colour and design) to be installed in Venice, at the Punta della Dogana. It’s funny because we’ve always wanted it to be in that particular place, above the canal. Quite appropriate, no?

I’ve been told that this year is your twentieth anniversary of collaboration, and you were expecting questions that are a little more fun and out of left field…

ME: No, we’re perfectly happy to be interviewed, but over the years people sometimes keep asking us the same questions, and it’s getting a bit routine-like.

So what’s one thing about your practice that you’ve always wished people would ask you but don’t, and that you really always wanted to talk about?

ID: Oh god, now you’ve thrown the ball back at us! That’s a good one, I’ll have to think about it.

ME: I don’t know if I can answer that question specifically, but I do wish that people would ask us fewer questions about formal issues, and about anything linked to the art market, for sure. Because that’s what our art is about—not to fulfil any specific purpose, not aiming to be “efficient” in any sense, and removing the focus from the mainstream idea of exaction, materialistic valuation and functionality. Failure is such an underestimated virtue. No one wants to show their failures in our Facebook-profile-driven society. Most of our works are dysfunctional, and they might not even look like sculptures in a traditional sense when you first see them—like our diving board, for example.

“It’s the depiction of the struggle between emotional strife and dependency that really speaks to us”

ID: We’re also always asked, “How do you work together?”, which is of course a very relevant question to ask any artist duo, but it’s one that’s impossible to answer. It’s such a symbiotic process that has changed over the years in ways we can’t describe. It’s like asking someone, “How does your relationship function? How do you live together?”

ME: I think it’s also tricky because our roles have alternated so seamlessly and without us noticing throughout the course of working together. We don’t always perform the same tasks, and I don’t just mean with regard to our art. In our working process and in our way of interacting we are constantly changing.

ID: But people tend to think that you’re the bad cop and I’m the good cop because I’m always smiling.

What kind of challenges have you had to overcome from working together over two decades?

ME: If you’re working alone, you can just say, “Ah, fuck this, this is shit,” and drop a project. Of course you have a different responsibility when you are two. But being two also makes everything more meaningful. It is so much easier to withstand any pressure, and sharing our experiences is what makes it worth it.

Your collaborative work began at a point when the two of you were immersed in very different disciplines. How have your thoughts and artistic direction evolved over the years?

ID: In the beginning it was a lot cleaner, conceptual and minimalist, I’d even say we were quite dry and the works were mostly rooted in direct references to the art world.

ME: I think that our fascination with the “art world” came from the fact that we never had any formal training in art, and so we began by approaching it from an outsider’s perspective. We were enchanted by the classic notion of minimal art: how to subvert the institutional power structures and the language surrounding these. It was all a mystery to us.

ID: But then after a while we got fed up with all of this because we thought our work was becoming too self-referential. So we started thinking about how to expand our practice to include ideas and concepts, still surrounding institutions, but perhaps in a more intimate and personal way. During the past few years we have allowed ourselves to work with narratives—some of our installations have even been inspired by filmmaking and nineteenth-century interior painting. In these installations and exhibitions, we have developed various characters that we use as a means to speak about certain existential topics.

Is there any one character that really resonates with you and that you continually use as a point of reference?

ID: For me it would definitely be a character from a film. We’re kind of obsessed with Ingmar Bergman and Michael Haneke. The characters in Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage, for example—they’re quite messed up in many ways. We draw from them and have included elements of these fictional relationships in our work. Mainly, it’s the depiction of the struggle between emotional strife and dependency that really speaks to us. There’s actually a sequel to that film called Saraband, which is not as well known, where the protagonists Johan and Marianne meet again when they are very old, despite their obvious irreconcilable differences. I like that element of masochism in both films.

ME: There is an incredible humanity surrounding these two characters.

When you look at a space and begin planning for your works, how do you decide to blur the boundaries between truth and fiction?

ID: When we paint a room over and over again for twelve hours, we’re testing the reality of the act of painting in a way. We exhaust this act. The repetitive motion becomes a type of fiction that collapses logic around us. Is the painting then about its formal qualities, or is it about the gesture of painting? In the same way, we ask these questions when we make our installations—when we transform an art space into, say, a domestic-looking interior.

ME: The diving board example you raised is actually quite a good one. It’s fun because people can certainly recognize the design of a diving board, but they aren’t quite sure what it is any more when you take it out of its familiar context and place it in a museum. Museums are such odd architectural entities. They are meant to be public spaces, but they seem incredibly private. Visitors constantly feel like they’re intruding into somebody’s private collection. At the same time, the museum is also presented as a space in which people should openly socialize. There’s no need to look very far to scrutinize the paradox of “public space”. It is in itself the embodiment of both truth and fiction.

That’s what Tomorrow at the V&A was about as well—turning this very personal institution into something that looked even more private—someone’s home—with its own unspoken rules and strange narratives. But at the same time visitors felt much more relaxed and welcome in this domestic setting.

Tell me more about exhibitions this year.

ME: Well, Tomorrow is getting its sequel in New York, called Past Tomorrow, at Galerie Perrotin. Norman Swann, the fictional architect from the original installation, has moved into a much smaller apartment on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, where he has to fit everything from his grand South Kensington apartment into a one-room flat. It’s been fun to develop this character further: Norman has already been to New York before, in the eighties during the height of the AIDS crisis, so he’s familiar with it, and he has ambivalent emotions about moving back there. It sort of liberates him and depresses him at the same time. It’s very different from the stiff, upper-class environment of West London that he’s become accustomed to.

ID: I think Norman finds himself a freer man in America than he does in England, and to a huge extent the exhibition is a reflection on how the concept of “Europe” has changed over the years. Imperialism has long become outdated and Eurocentric ideas are universally condemned. Europe is now a Disneyland of classic ideas, and he’s happy to be free from all that falsehood. We also have an exhibition at Plateau, Samsung Museum of Art in Seoul that will run from mid-July to October. We are transforming the main gallery space so that it resembles an airport. The part of the museum that has temporary exhibitions is called Plateau and so we have titled our show Aéroport Mille Plateaux, after the book A Thousand Plateaus by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari. We’re interested in the way that Deleuze analyses transitory spaces; airports are sort of non-spaces.

ME: Places you pass through in order to get to another destination. We like to create spatial set-ups without any real function. Like Prada Marfa, for example, which showcases handbags and shoes from the 2005 Prada fall/winter collection, but the door is closed forever, so you can only window-shop.

ID: Obviously this doesn’t stop some people from trying to get in, though. That’s what’s so fantastic about observing how people’s interactions with our art changes over the years. Like how you climbed on to our diving board.

ME: I love that, honestly. Disrespect for artworks is such an underrated value.

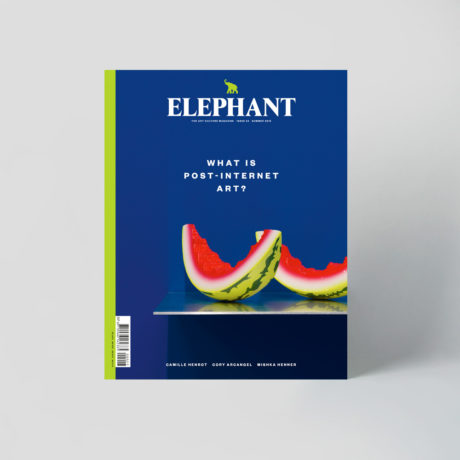

This feature originally appeared in issue 23

BUY ISSUE 23