Is gaming ready to take its place among painting, sculpture, photography, moving-image and installation as a key medium in the contemporary art world? After all, in revenue terms, the games industry is now larger than that of film and music combined.

Is gaming ready to take its place among painting, sculpture, photography, moving-image and installation as a key medium in the contemporary art world? After all, in revenue terms, the games industry is now larger than that of film and music combined.

But to position gaming merely as an artistic format when it comes to the leap into the visual arts sphere might be restrictive. Both inspiration and departure point, it is not confined by scale, place, duration, nor by the laws of physics or reality. Its founding characteristic is the defiance of traditional limits, and its potential stretches beyond the confines of tool, medium or practice.

When selected to participate in Worldbuilding: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age, a major new group exhibition curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist at the Julia Stoschek Collection in Düsseldorf, the 34 participating artists were each asked: ‘What are the qualities of a good video game?’ Their responses differ wildly, from “mind-expansion” (new media pioneer Suzanne Treister) to “solid gameplay, a narrative score, attitude and also heart” (Afrofuturist Jacolby Satterwhite).

By reframing known identities and scenarios in fictitious landscapes, the works in Worldbuilding draw new attention to how our own societies are organised, and how obstacles to its improvement or revolution might be removed. Here are our highlights from the show.

Rindon Johnson, May the moon meet us apart, may the sun meet us together, 2021

Rindon Johnson’s virtual-reality world is populated with ‘Bists’, limbless, ocean-dwelling creatures which resemble giant blood cells or jellyfish. Inspired by the movements of the octopus, the Bists are part of Johnson’s environmental commentary: they filter plastic from the oceans, “absorbing our detritus to give the sea a chance.” Moving among them, the feeling is one of complete disconnection from reality, a journey to an amniotic world of suspended movement and strange animalism.

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, SHE KEEPS ME DAMN ALIVE; DECISION MAKER, 2021

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley politicises the game space by creating a first-person point-and-shoot arcade game structured around the need to protect Black Trans Lives. The participant uses a pink 3D printed gun as the joystick to navigate multiple levels of carefully chosen foes, from White Supremacy Workers to Electric Nerves (a composite creature of transphobia and electricity). The narrator examines the player’s own agency within social, political and digital spaces. “Why does it feel good to be holding a controller that is a gun?” they ask the viewer.

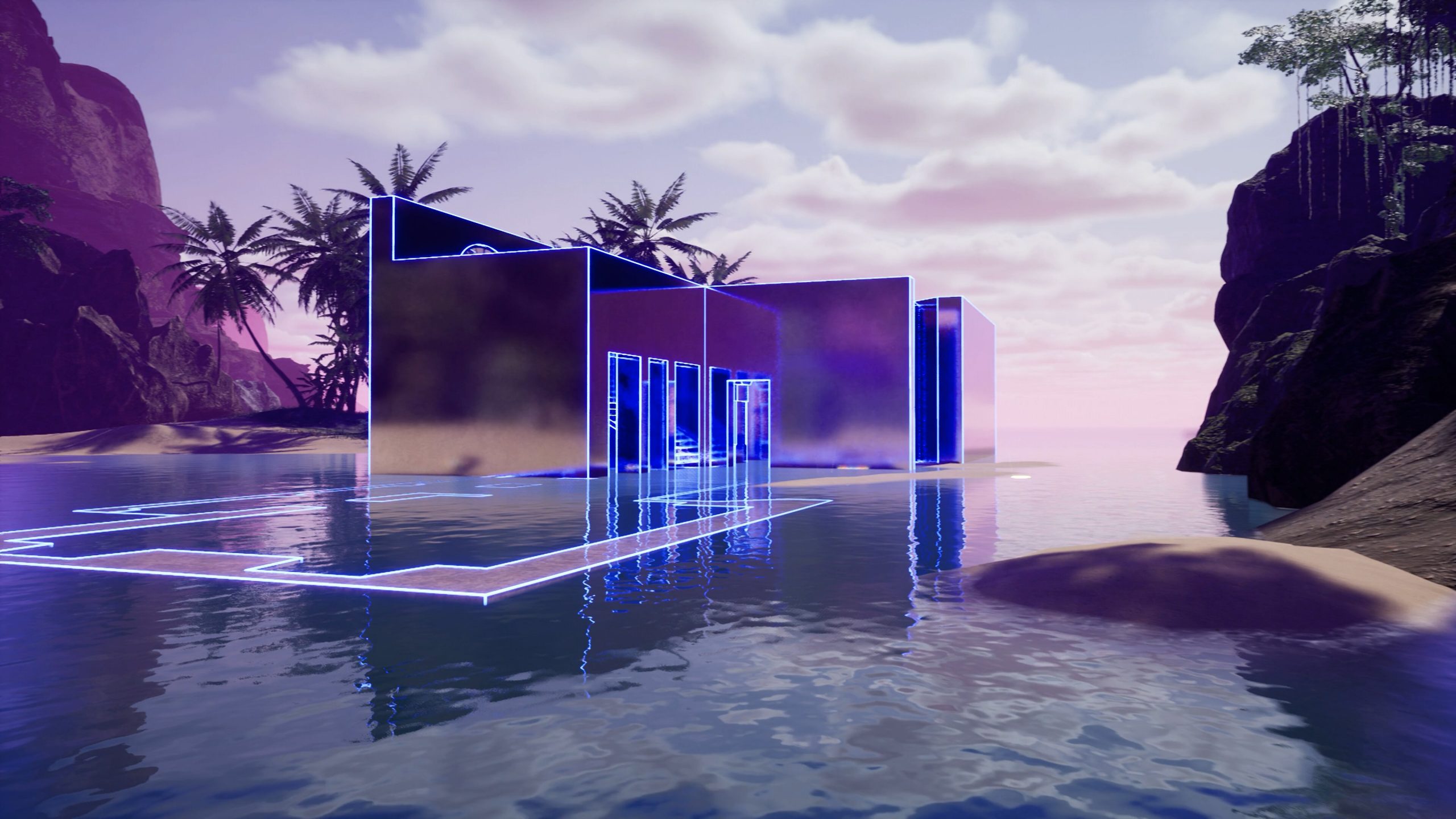

Lawrence Lek, Nepenthe Zone, 2022

London-based artist and musician Lawrence Lek continues his use of first-person exploratory gameplay in Nepenthe Zone,

set on a tropical island where the player’s mental space is mirrored by the iridescent building walls. This sense of place is complicated by references to “the doorway effect”, which describes the experience of entering a room and forgetting why you did so. The island is an adapted version of the setting of Lek’s 2065 and Geomancer, and poses probing questions about the nature of memory and consciousness. “You came here to forget,” a narrator says. “Don’t you remember?”

View this post on Instagram

Transmoderna, Terraforming—Terraforming, 2021

Hybrid collective Transmoderna presents an interplanetary virtual-reality experience as part of their ongoing Terraforming project, creating three cinematic scenes for the participant to navigate. The laws of physics are suspended, allowing the player to vault into the air and explore the interplanetary landscape in multiple directions. Sea levels rise and fall in the distance, while coral-like forms surround the viewer’s dwarfed perspective.

Jacolby Satterwhite, We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other, 2020

Jacolby Satterwhite uses the fictional potential of the gamespace to explore idealised versions of contemporary reality, especially relating to Black life and oppression. We Are in Hell When We Hurt Each Other is a “virtual pastoral concert space” where Black female robots (intentionally designed to resemble Grace Jones) dance and parade in unison. Footage from Black Lives Matter protests root the digital world in today’s conflicts, bringing a social impulse to the playful escapism. “Unrest has gone haywire, with paranoia and the elite gaining more control over the masses,” Satterwhite says. “I had to pare down my feelings and build up a utopia for Black survival.”

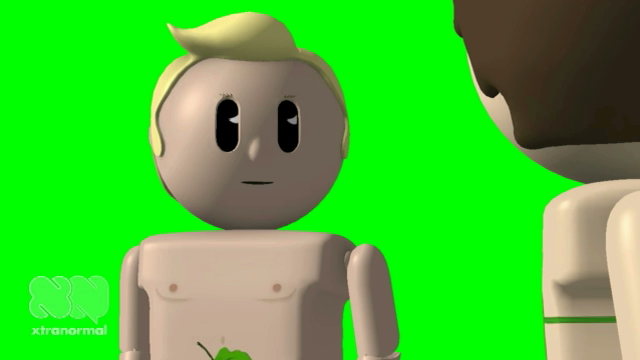

Frances Stark, My Best Thing, 2011

Humour and self-conscious parody are key components in the way artists use gaming technologies. In My Best Thing, artist and writer Frances Stark recreates her online sex chat with two young Italian men, here represented by computer-generated 3D Playmobil dolls. First presented at the 54th Venice Biennale, the ten-episode work becomes increasingly intimate and intellectually expansive, with Stark leaving the viewer with pressing questions about the nature of knowledge, language, loneliness, and the possibility of digital integration into social life.

Larry Achiampong and David Blandy, A Lament for Power, 2020

Artist duo Larry Achiampong and David Blandy’s A Lament for Power unpacks the cultural and medical legacy of colonialism by critiquing existing games and crafting a visual and audio response. Dedicating their work to Henrietta Lacks, whose cell line was used and immortalised without her consent in 1951, the pair craft a response to the racist treatment of Black characters in Resident Evil Five. The work serves as a dedication to exploited Black women, inviting us to consider our own desires against those whose autonomy has been violated, whether in the physical or the digital world.

Ravi Ghosh is Elephant’s editorial assistant

Worldbuilding: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age is at the Julia Stoschek Collection, Dusseldorf, until 10 December 2023