“God knows inventing a universe is a complicated business,” science-fiction and fantasy writer Ursula Le Guin quips in the introduction to her Hainish Cycle series. In the tentatively post-pandemic world, speculative world-building has arguably never been more urgent. How can we begin to imagine the future? What kind of universe do we want to build?

These questions are central to New Worlds, an experimental series of talks, screenings and performances at Somerset House, which, as curator Alice Bucknell puts it, “speculates on what it means to create new and alternative worlds as a collaborative antidote to an apocalyptic present.” These worlds are not necessarily utopian. Roaming and polyphonic, they are, like Le Guin’s fictions, systems of entanglement.

New Worlds revels in different perspectives and media, from ecological consciousness to sound as a world-making tool, non-human mythologies to new language structures to ritual environments, and that’s just for starters. Bucknell proposes that magic and technology are not fundamentally opposed, but instead can and should be generatively intertwined.

The series spins around nine artists and writers whose practices, as Bucknell says, “are situated within that threshold.” Let’s take a look at their work and worlds…

Alice Bucknell

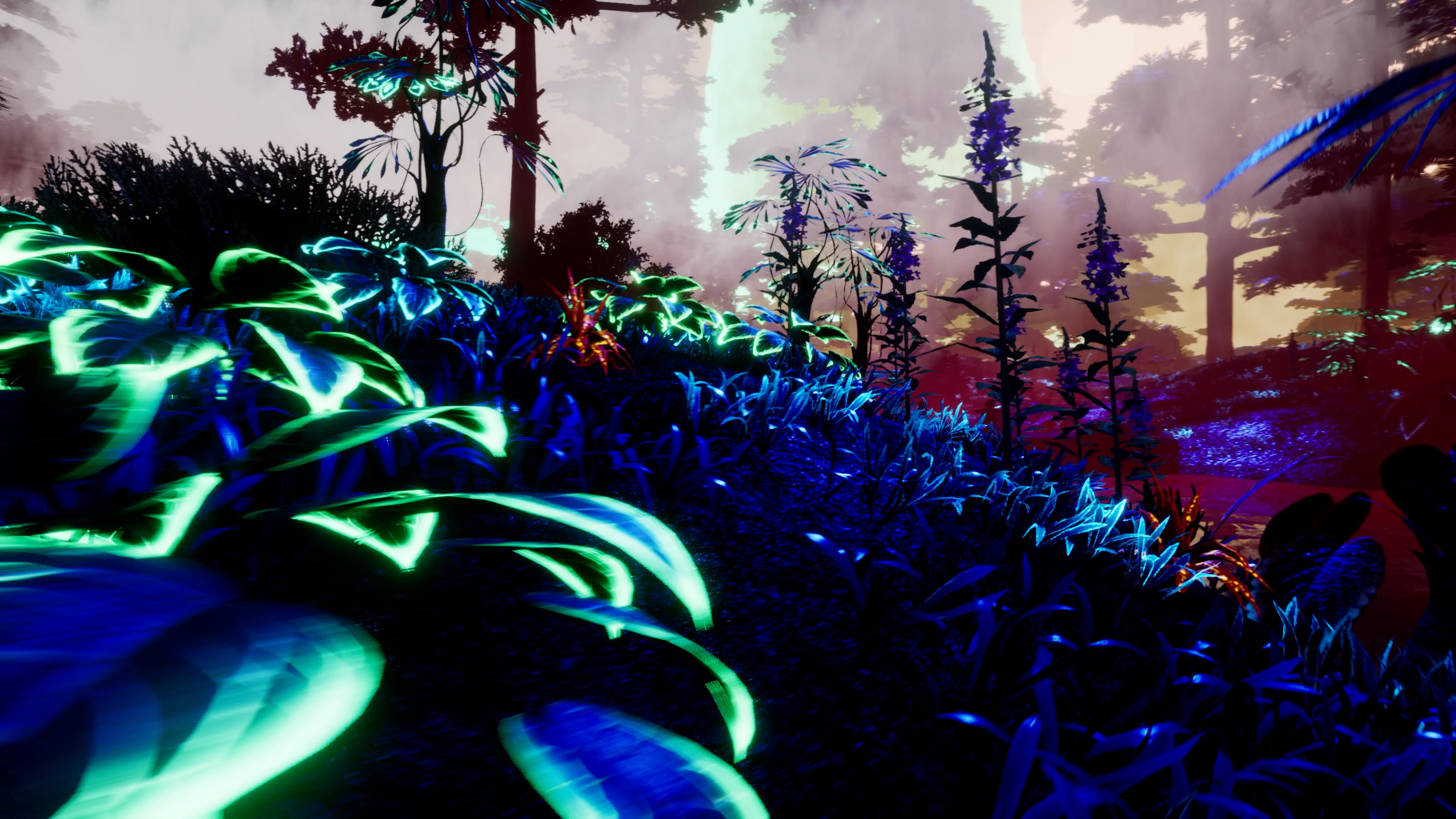

“The technological has always been mythical, and vice versa,” Bucknell says. An American artist and writer based in London, her own practice sees her operate primarily through game engines, exploring interconnections between architecture, ecology, magic, and machine intelligence.

New Worlds draws directly from Bucknell’s work with New Mystics, a digital platform exploring the work of artists who merge magic and myth with various technologies. It features both human and non-human voices, with texts co-authored by GPT-3, an AI system that can mimic human language, which Bucknell describes as “a kind of digital oracle.”

“Bucknell proposes that magic and technology are not fundamentally opposed, but instead can and should be generatively intertwined”

Joey Holder

When asked how she sees mythology and magic merging with new technologies, Joey Holder quotes science fiction writer Arthur C Clarke: “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” A visual artist, producer, and director of gallery and creative research space Chaos Magic in Nottingham, Holder suggests that “magic and technology are entangled concepts, suggesting that it might be easier to think of them both as tools and extensions for our limited human capacities. Both have the power to change the way in which we see and interact with the world.”

“It might be easier to think of magic and technology both as tools and extensions for our limited human capacities”

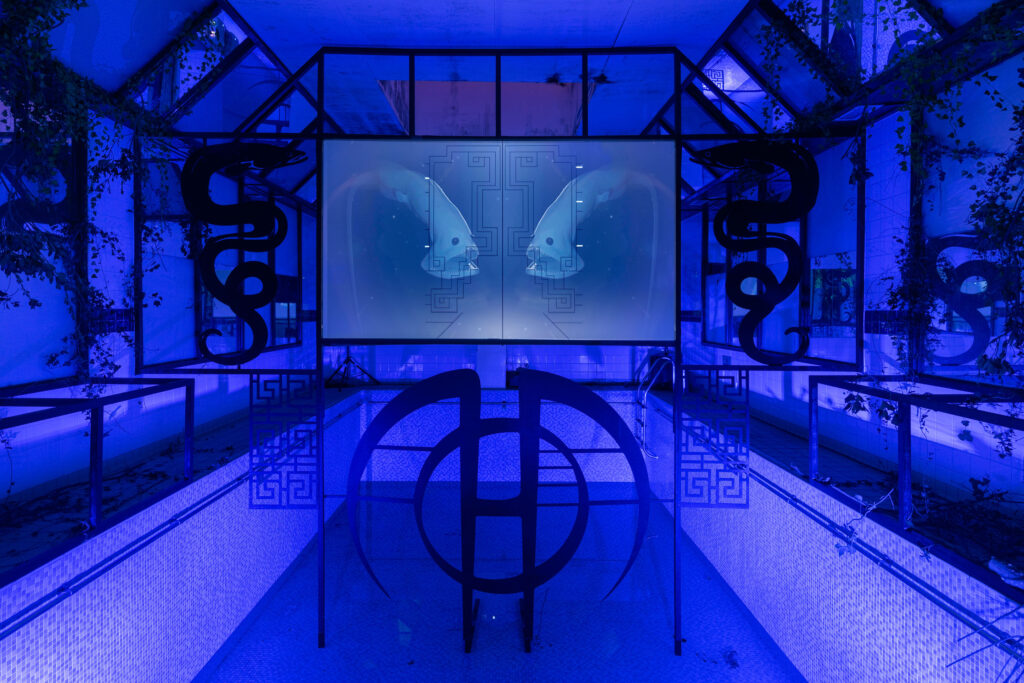

In her own work, Holder creates fictional worlds and constructed environments that respond directly to real world events. Each artwork is conceived as a ‘set’ with unique filmic, narrative, architectural, visual and sound elements. “I’m attempting to address these big questions,” Holder says, “confronting things yet unknown, regarding the future of science, medicine, biology and human-machine interactions and how these affect our beliefs.”

Alex Quicho

As an associate lecturer in foresight and speculative futures at Central Saint Martins, Alex Quicho works from the belief that “from the predictive qualities of ancient oracles to the deep dreams of artificial intelligence, technology has long contained magic, and vice versa”. Quicho is also the author of Small Gods (2021), which deconstructs the mythology of the drone in all its terror and transcendence.

She acknowledges that “mythology and enchantment can be instrumentalised for nefarious ends: think vast corporate fictions and evasive, overzealous PR”. Yet she suggests that “ancient or alternative myths can also help us recover a sense of agency over our collective fate, even if only through total surrender to the uninstrumentalisable, the uncontrollable and unknown.”

Lawrence Lek

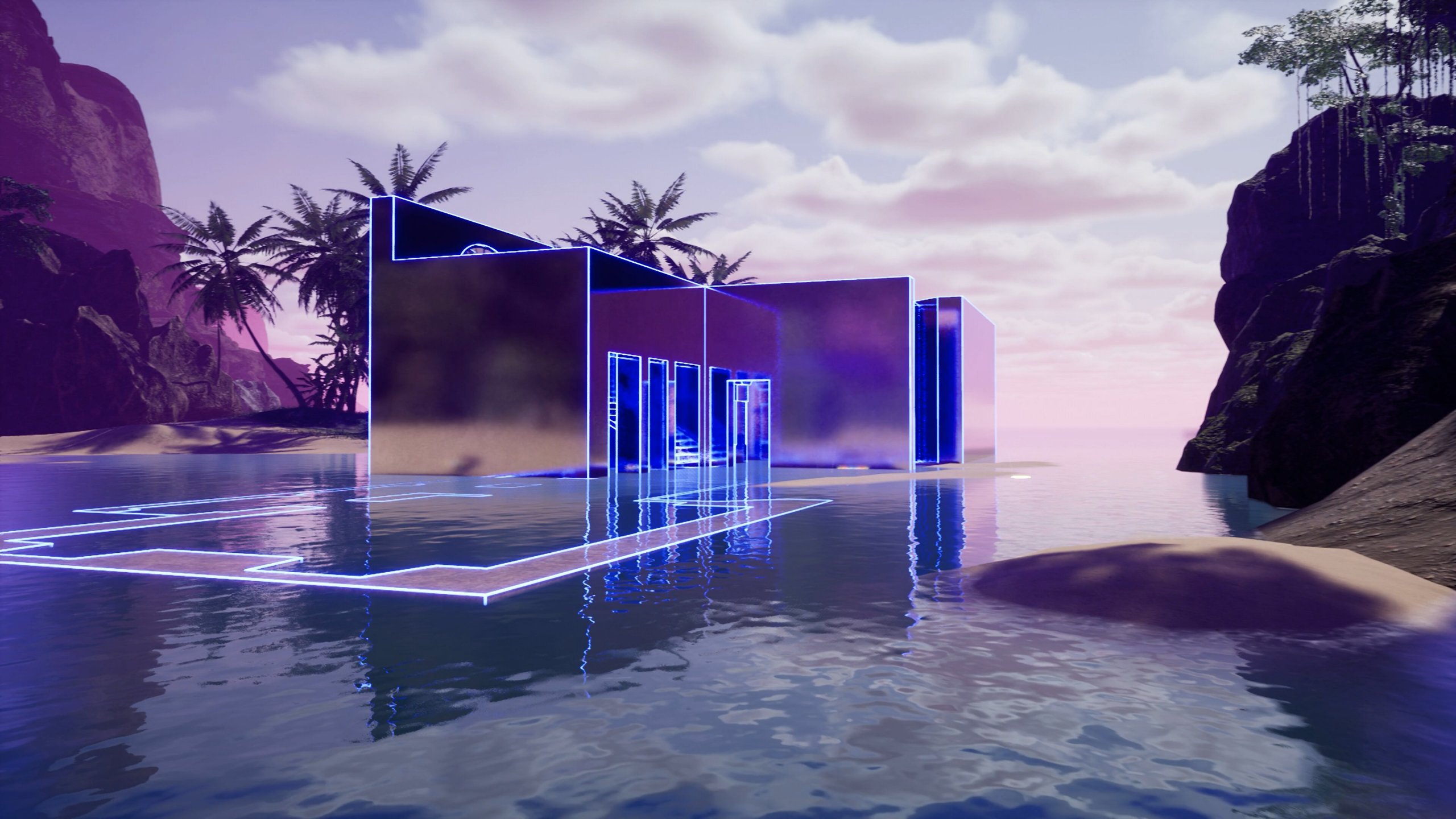

This sense of surrendering to the unknown pervades the work of Lawrence Lek, a multimedia artist, filmmaker and musician based in London. “I’m interested in mythology because it’s a form of storytelling that is largely anonymous and symbolic,” Lek says.

His VR renderings, which are often set within a Sinofuturist universe, explore the intersection between real and imagined worlds. They layer and repeat, drawing the viewer into a lush, hypnotic and increasingly-disorienting matrix. For Lek, this is one of the essential appeals of mythology, which, he suggests, “operates like a matrix of memories and narratives which can never be attributed to an individual author or creator, but rather to a collective”.

Evan Ifekoya

A multidisciplinary artist and energy worker, Evan Ifekoya’s practice challenges existing systems and hierarchies of power to recentre and prioritise the experience of the marginalised. Like Lek, their work draws on the affective and existential dimensions of sound, and begins by asking what it would mean to start from a place of abundance. How can listening be understood as a kind of healing?

“My concern is with technologies, whether new or ancestral, that connect us to deeper levels of our (self) awareness, embodiment and consciousness,” Ifekoya says. Their recent moving image and audio works “touch on how healing frequencies… resonate in harmony with the cells of our body, and how the drum, a primordial technology, is a mechanism of consciousness reversal.” Listeners are encouraged to attune to their own resonant frequency or natural vibration.

Himali Singh Soin

An artist and poet based between London and Delhi, Himali Singh Soin uses metaphors from outer space and the natural environment to construct imaginary cosmologies of “interferences, entanglements, deep voids, debris, delays, alienation, distance and intimacy”. Using found footage of obsolete communication technologies, ruptured with static and glitches, her 2017 video work, Silicontology, exposes the “geology of media”, its permanent imprint on the world.

Ultimately, her work prompts the viewer to think of machines, not as distinct technological entities, but “as hauntings, as weavings, as code, as poems that could bridge our many worlds rather than separate them.”

Sammy Lee

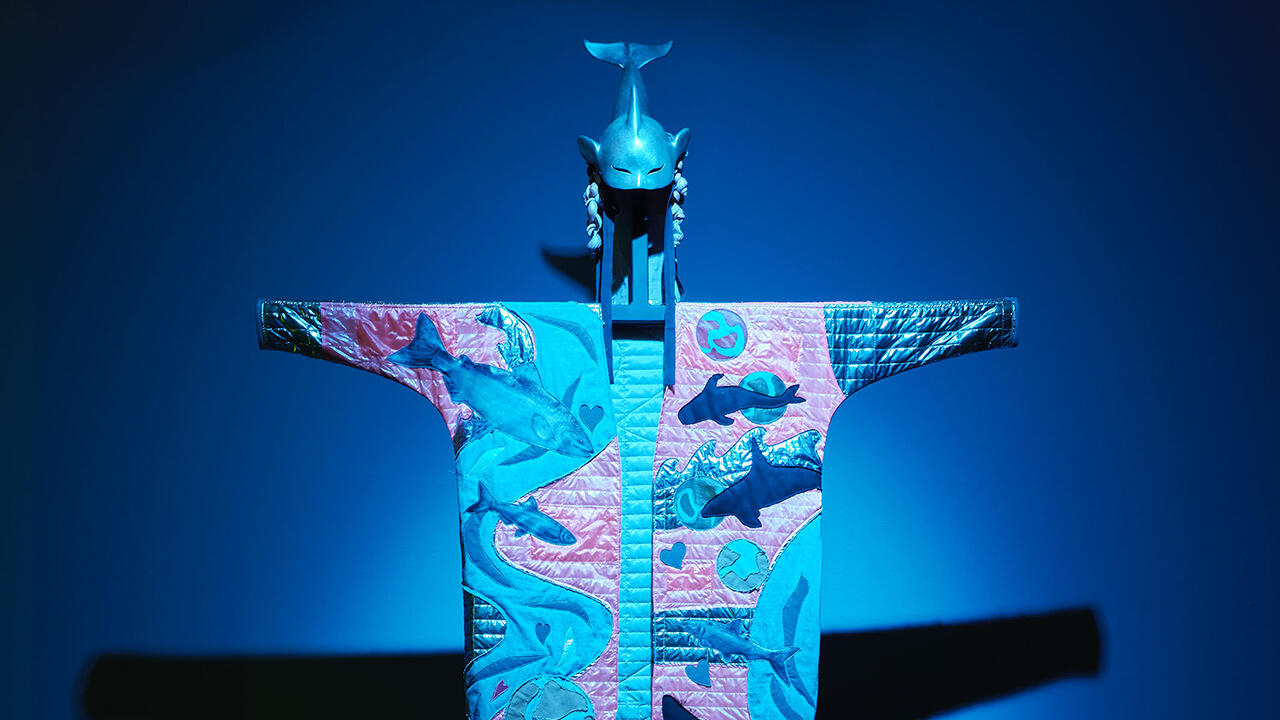

“I’m particularly interested in the reincarnation of traditional mythic forms through new technologies,” Canadian-born Korean artist Sammy Lee says.

Her work spans audiovisual artworks, CGI film, real-time simulation and light installation, creating complex visceral worlds, which often propose a way through an apocalyptic present by thinking and feeling with other species. Yet despite working to unearth new forms of knowledge, Lee stresses that, “in my animated and simulated worlds, magic is ordinary”.

“I’m particularly interested in the reincarnation of traditional mythic forms through new technologies”

Zadie Xa

Influenced by science and speculative fiction writers, from Octavia Butler to Audre Lorde, Korean-Canadian visual artist Zadie Xa thinks of storytelling as a project of critical distance. It becomes a way to interrogate cultural or environmental challenges that may be too difficult to confront head-on. Yet that distance can also be a kind of magic. “I choose to continue the tradition of sharing stories as a methodology for magic making and technological advancement,” Xa says.

Her practice is also resolutely practical: “Whether it’s through creating pictures or objects, I feel most rooted in storytelling when I am constructing in the studio.”

“I choose to continue the tradition of sharing stories as a methodology for magic making and technological advancement”

Bones Tan Jones

“I think it’s exciting and terrible how new technologies are replicating some of the world’s magical mysteries,” Bones Tan Jones says. “I am unsure how magical it becomes when the Earth is sacrificed for the sake of new technology,” Bones says. They explore this tension in their expansive, spiritual practice which traverses pop music, sculpture, ritual and video work in order to propose visions for an alternative future.

“Through envisioning dystopian futures full of optimism and tragedy, mysticism and destruction,” Bones hopes their work can help us to envision how we might “shift into more sustainable relationships with the world around us”.

OMSK Social Club

Unlike many art collectives, OMSK is run on the principles of anonymity and impermanence: the names and even number of members in the group remain unknown. Their works are ephemeral experiences, formed of hybrids of Real Game Play (RGP) and Live Action Role Play (LARP). Their work sets out to “open up parallel worlds through the methodology of role play, with the aim to eavesdrop on a potentially not yet lived reality to use it as a test site for this one.”

For OMSK, “technology is a material extension of magic and mythology.” They argue that it was mythology that “animated the mind into building technological codes and devices that we can access daily”.

Eloise Hendy is a writer and poet living in London

New Worlds is at Somerset House Studios, London, until 21 July 2022