A woman holds two pale pink semicircles on a silver platter. She holds them as if she were serving them at a feast, as if these tokens were delicacies on which to dine. The woman is St. Agatha, and she is holding her own breasts. A Christian virgin who refused to give in to the demands of a rich suitor, she underwent a number of tortures. She was stretched on the rack, burned, whipped and—as her iconography resplendently depicts—her breasts were cut off with pincers.

A female castration of sorts, the surreal scene of Agatha and her severed breasts can be spotted throughout Italy and indeed the world. In Italy however, the connection in pointed. At the start of February when celebrations for her feast day begin, colliding with the frenzy in the lead up to Valentine’s day, little breast cakes emerge, red cherries placed onto domes of soft sponge and sweet ricotta. There is a beauty in this culinary transformation, a means of remoulding violence into nourishment, but there is also a sinister undertone.

When one learns the story, the contrast is jarring. Yet the consumption of women—even when literal—hardly comes as a surprise in contemporary culture (dare I mention the recent Armie Hammer scandal?). How often have men broken down the bodies of women in the world, both literally and metaphorically? On billboards women’s bodies are segregated, their features cut up; in magazines their legs, lips and breasts speak. Breasts in particular have always appeared as a site of twinned tension, coming as a pair it’s perhaps appropriate that they remain sites which bridge the gap between sexuality and sustenance, the comfort of maternal affection and the thrill of titillating eroticism.

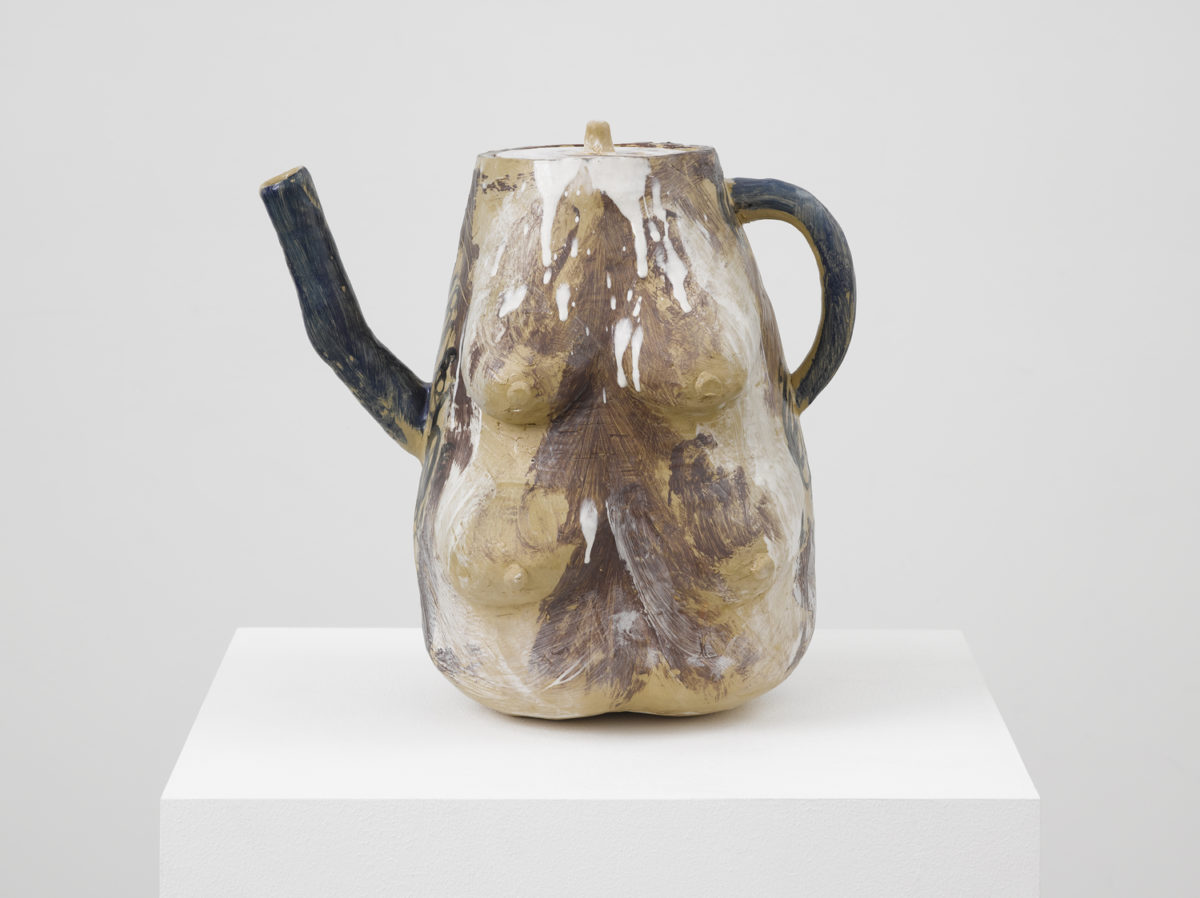

Maria Roosen, Borsten Bessen, 2009

Agatha would have found an ally in today’s women artists, for whom breasts have become a powerful site for reclamation and satire. Polish artist Alina Szapocznikow‘s Dessert series (1970–71) involves a silver platter, with thin slivers of breasts cast in candy-shop coloured polystyrene and piled high. Concave and incomplete, these luminous shavings of skin are a stark reminder of the transformation of St. Agatha’s torture from violence to edible delight.

Dutch sculptor Maria Roosen presents ‘breast berries’ in which glass sculptures are clumped together, gathered like grapes on a vine: lush, bounteous and fertile. Other series see the metonymic breasts become, in Roosen’s words her “tools for feelings”. The variety of colours and finishes (clear, coloured, doodled, marked) reflect the diversity to be found within the vast spectrum of women’s bodies. The semi-spherical forms are reminiscent of the globe itself, with isolated objects set up as independent worlds.

“Domes, spheres, cylinders, eggs, ovals, containers: how do we define the shape of a woman?”

“I wanted to hang the reflecting breasts on the wall at eye level so that the viewer is mirrored in them,” Roosen explains. “It’s funny that you are drawn toward the teat by the reflecting breast and that at the same moment the whole surroundings are absorbed in that breast. A normal mirror simply throws your reflection at you, but this one imprisons you.” Roosen’s breasts encompass the viewer, they present a new kind of appetite, in which the breast moves from its position as a passive object to an active seeking element.

In 1984, two severed breasts sat inside a plastic box. Viewers were invited to place their hands inside the Perspex container and fondle the isolated body parts. There was just one catch: the serrated edge of sharp knife-blades emerging from the sculpted nipples. These breasts were not idle, they were protected. Those who dared to enter, who dared to touch, would receive a just reward. Renate Bertlmann‘s Breast Incubator inadvertently recast the story of Agatha, presenting her severed breasts as protagonists in their own right, autonomous objects able to defend themselves, owning their own kind of reflective violence.

In an interview in 2015 with Gabriele Schor, Bertlmann noted how “The object Messerbrüste [Knifebreasts]… caused strong reactions in men, but above all in women. Men felt threatened, and women described the piece as anti-feminist because of its perceived connotations of masochism and self-mutilation. They couldn’t see that the aesthetic construction demanded a knife inserted in the breast as a means of rejecting its designated role as a fetish and object of desire.” The blade was not penetrating the breast, it was rising from within it. It did not harm, it weaponised the previously passive site and gave it protection.

Linda Nochlin’s famous assertion that women should “destroy false consciousness” in her pioneering essay ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ speaks to the destruction of false physicality. Just as women have been built and broken by the male gaze over the years so too can we see how they desire to break these perceptions apart themselves, and through this violent rupture gain control over how their physicality comes to be. Domes, spheres, cylinders, eggs, ovals, containers: how do we define the shape of a woman? More importantly, should we want to?

For French artist Laure Prouvost, the image of the isolated breast grows larger in her work as the years pass. In the French Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale, the aqueous world of her Deep Blue See Surrounding You was filled with ‘cooling systems’ fountains ‘for global warming’ which saw glass breasts spouting water out into the air, held aloft by performers like elegant parasols.

“Agatha would have found an ally in today’s women artists, for whom breasts have become a powerful site for reclamation and satire”

- Laure Prouvost, Cooling System 4 (For Global Warming), 2018 (left); We Will Feed You, Cooling Fountain (For Global Warming), 2018 (right) © Laure Prouvost, courtesy Lisson Gallery

At Palais de Tokyo in 2018, her central sculptural installation Ring, Sing and Drink for Trespassing took the work of her fountains further. Of these giant sculptures spouting water, the gallery’s website states: “a large fountain of breasts is waiting to feed you”. Prouvost’s mammary dislocation comes as a form of nourishment, a hyperbolic play in which the nourishment of art allows the body to resist classical connotations. The isolation of the breast is not pained but empowered, enhancing its potential as a symbolic metonymic object: “I think of the woman’s body as a generous thing,” says Prouvost, “in its feeding, in everything it does.”

In her film Objectify Me and Last Supper performance, German artist Annique Delphine makes the conflation of different appetites literal: round red nipples bulge from scoops of melting ice cream adorned with multicoloured sprinkles, or protrude from the circular hollow of a doughnut. For Delphine, the collusion of the female body and edible objects provided a new language. “Objectify Me was the only way I knew how to express my pain and confusion about how women are regarded as things rather than people,” she says. “How our nudity is used to normalise this and also to justify violence against us.” The process of creation was a liberation, while also a means of reproducing trauma, addressing “the very narrow ways in which women are allowed exist without censure. And how exclusive these ways are. How many of us don’t fit the stereotypical expectations of what society defines as ‘woman’?”

Breasts are weighted with expectations of gender. Their form and their function, which itself changes over the years, acts as a point of conflation wherein the arduous triptych of virgin, wife, mother is rounded into one. Is it any surprise that artists wish to explore and interrogate these signifiers? Artists have found myriad ways of untethering the societal expectations these body parts carry with them, using their reconfigurations of the body as a means of expanding the possibilities of what people can be. By deconstructing women, they’ve reinvented them.