Hypnotic close-ups of a mouth, then an eye: desire and scrutiny. Saul Bass’s opening title sequence—his first for Hitchcock

Hypnotic close-ups of a mouth, then an eye: desire and scrutiny. Saul Bass’s opening title sequence—his first for Hitchcock

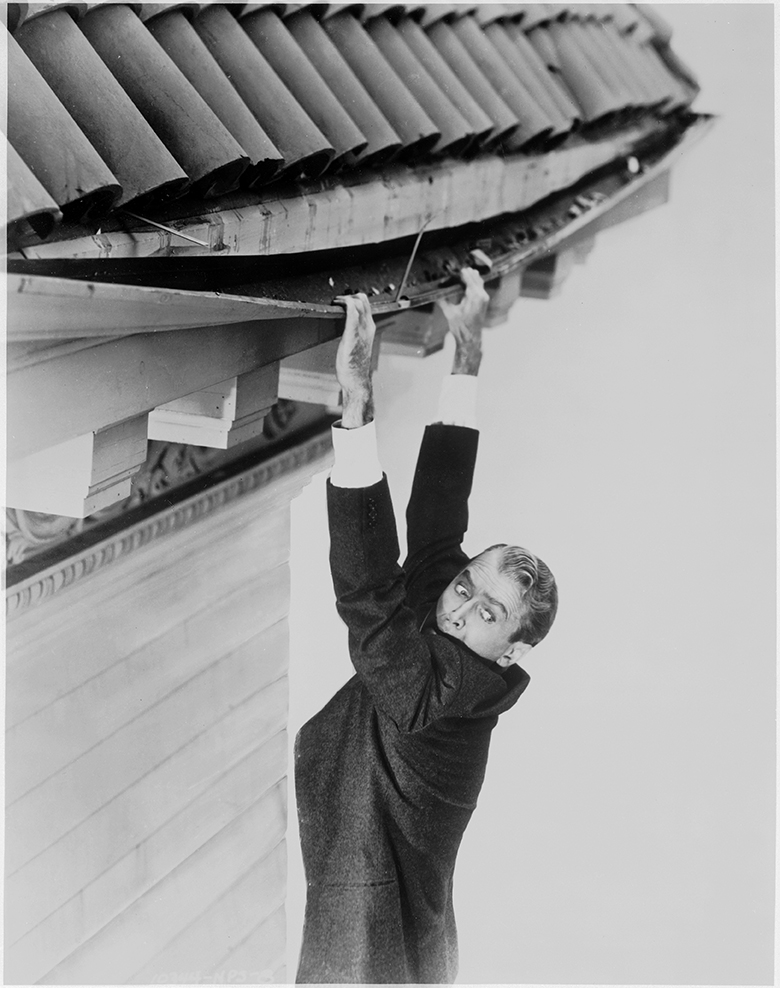

—hooks you in while Bernard Herrmann’s unrelentingly gorgeous score, both alarming and romantic, envelops you. The dreamscape of dark California, with its towering bridges, pathless forests and oppressively oneiric neo-classical landmarks, is about to unfurl. Soon, Scottie, the acrophobic detective played by James Stewart, will be dangling precariously from a gutter, paralyzed by vertigo. Then we remember that there will be a Spanish mission, a bell tower, a woman and her doubles; alive, dead, painted.

French film-maker François Truffaut

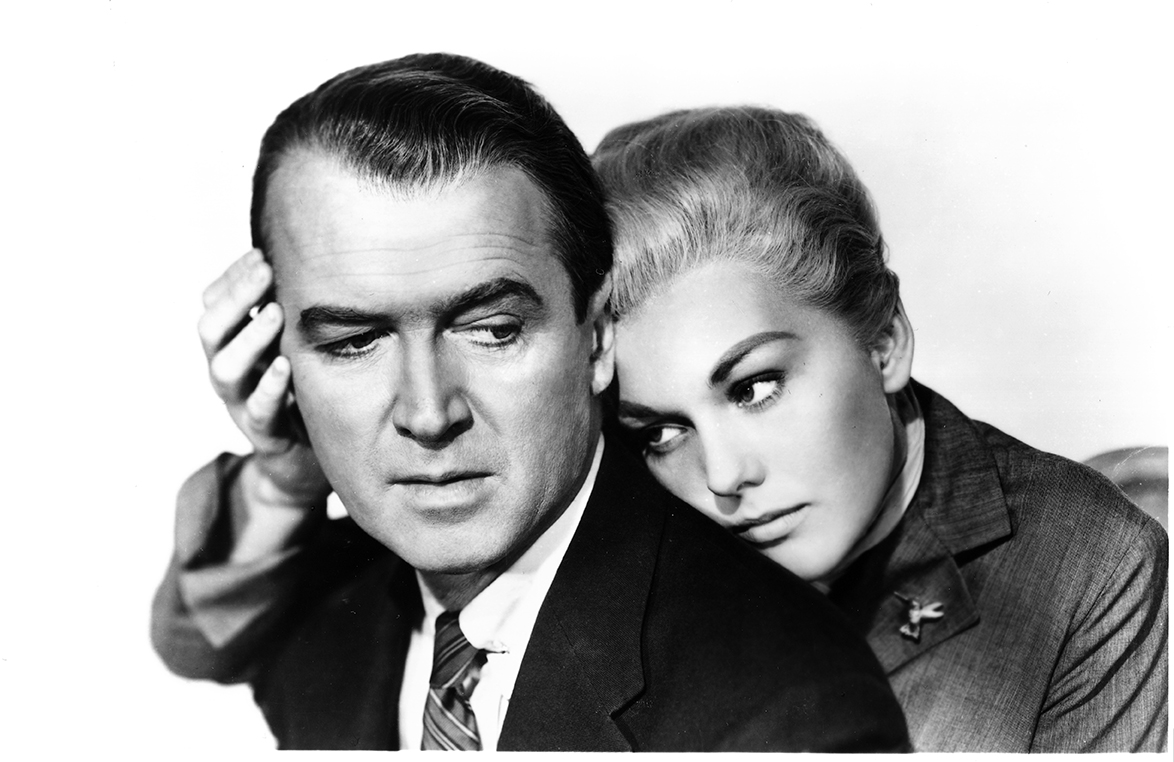

described Vertigo as a “bedside film”, meaning that it is a work we can store in our psyche and turn to whenever we want, so powerfully is it wired into us. Its world is dense and crystallized, compressing within itself Hitchcock’s Catholicism; his interest in Freudianism, Symbolism and Surrealism; and ancient, medieval and modern myths. Scottie’s attempts to remodel the earthy Judy (Kim Novak) and bring his dead love, the otherwordly Madeleine, back to life (also Kim Novak, though her dual performance is so good that some 1958 critics did not realize that she played both parts) are reminiscent of Pygmalion and Galatea, Orpheus and Eurydice, or Jekyll and Hyde. Bernard Herrmann’s score is steeped in Wagnerian music, in particular the Liebestod theme from Tristan and Isolde.

Vertigo is being re-released in honour of its sixtieth anniversary, but its status as a masterpiece was only recognized fairly recently. It came out in 1958 with a whimper—neither a critical nor a commercial success. Hitchcock was a director with strong commercial sense, who participated in the financing of his films, so his future output was dependent on doing well at the box office.

“Vertigo, now lauded as a suspense classic, is an oddity, and anything but straightforward.”

The picture receded, was buried (Hitchcock withheld the rights for financial reasons) and became extremely difficult to see, unless you knew a collector who owned a copy. When it was eventually re-released in the 1980s it was hailed as a remarkable work (by Martin Scorsese among others), and since then has gradually risen into the pantheon of masterpieces, even managing (in 2012) to displace Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane from the top spot of Sight and Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time poll, after fifty years of undisputed rule.

Yet Vertigo, now lauded as a suspense classic, is an oddity, and anything but straightforward. The female love interest is killed after seventy minutes, for one thing. And where, in the original story (the novel D’entre les morts, by French writing duo Boileau-Narcejac), the revelation of the machination came at the very end, here it is given away much earlier. It was a daring move that even Hitchcock himself was unsure about. In short, Vertigo illuminates the degree to which the commercially-minded director was also an experimental artist.

Surprising twists are employed in the film’s use of suspense—Hitchcock’s specialty. There is a state of tension, where the spectator knows no more than the protagonist, and is waiting helplessly for the sword of Damocles to fall. When Scottie is tailing Madeleine’s car, following her along the turns of the San Francisco labyrinth in lengthy, undetermined, floating sequences that are the polar opposite of a dramatic car chase, we do not know any more than he does. Later “sightings” of Madeleine after her death are also expressive of a blurred uncertainty, teetering on the brink of hallucination. Nor does the film provide any catharsis, even when all is accomplished at the swift, implacable end. Scottie is left hanging over the abyss, devastated, and we share his sense of unrelenting angst.

This is suspense as suspension, irresolution, ache. There is no release, no nervous laughter when that pleasurable thrill of relief comes at last. We’re stuck, hovering anxiously. Is this perhaps why Hitchcock’s work has been appropriated so many times by contemporary artists? Because it taps into an obscure nagging; an inability to settle and relax? This year’s Art Basel included a short film programme, bringing together Lynn Hershman Leeson

’s film Vertighost (exploring the figure of the doppelgänger through the museum scene in which we see Madeleine from the back, as she looks at the portrait of Carlotta) and Feature Film by Douglas Gordon (author of the 1993 video work 24 Hour Psycho), which consists of close-up shots of the face and hands of a conductor, filmed while interpreting Bernard Herrmann’s Vertigo soundtrack.

Beyond direct reference, there is a kinship between Vertigo (which is all about tension and the gaze) and the unease created in such disparate works as Steve McQueen’s Static (2009), where the Statue of Liberty is filmed from a helicopter, the constant motion suggests a stuttering, anxious scrutiny of freedom, and the performance The Other: Rest Energy (1980), in which Ulay aims a taut bow and arrow at Marina Abramovic’s heart for several minutes, against the soundtrack of their anxious breathing and heartbeats. This is perhaps where Vertigo’s fertile inheritance lies, in time-based art media that capture the essence of Hitchcockian angst to their own end.

“The brilliant and perverse Vertigo expresses Hitchcock’s own obsessions in a succession of mise-en-scène and seduction manoeuvres.”

Of course, the director’s art has been a source of fascination and inspiration to film makers too, with Brian de Palma (Obsession 1976, and Body Double 1984) and Chris Marker (La Jetée, 1962 and Sans Soleil, 1983) positioned at either end of a spectrum, running from the commercial to the experimental. Vertigo arguably nourished those films that deliberately sabotage expectations of release from suspense and angst, such as Christopher Nolan’s 2000 Memento, where the amnesiac protagonist’s story is told backwards; David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001), with its dreamlike inextricable doubling; and Michael Haneke’s two versions of the terrifying Funny Games (1997 and 2007).

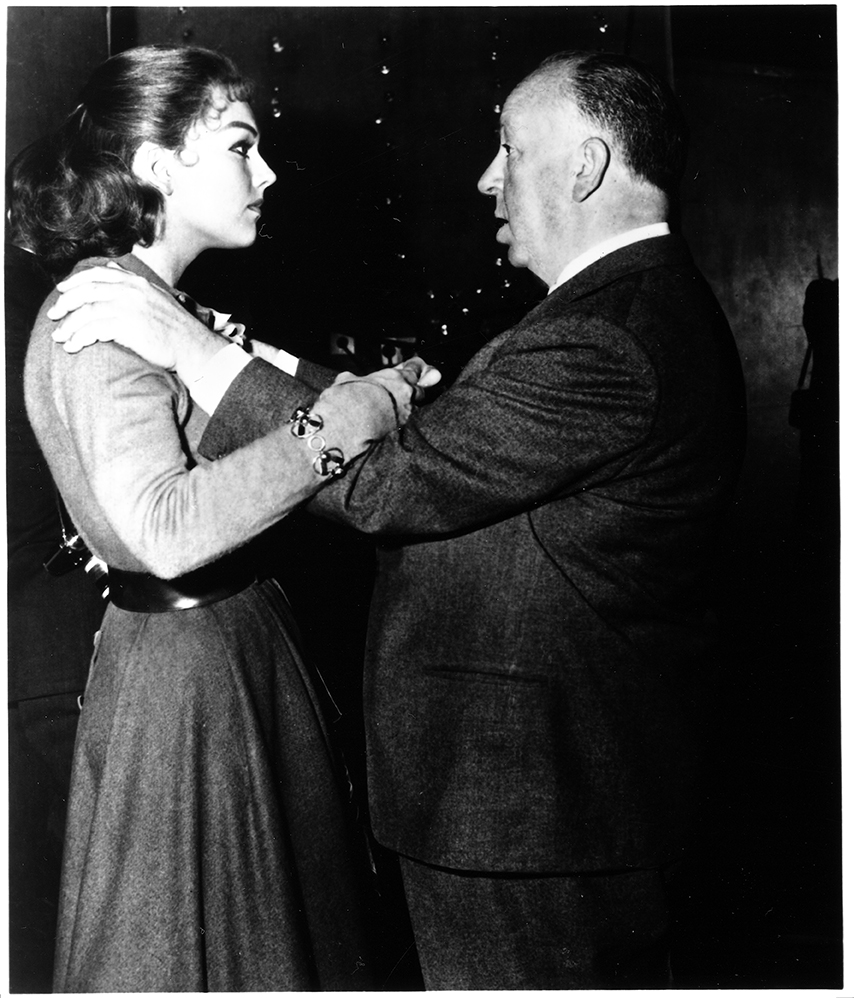

The brilliant and perverse Vertigo expresses Hitchcock’s own obsessions in a succession of mise-en-scène and seduction manoeuvres. Its unhinged story of love and possession is also about film-making, something that Kim Novak understood very well. She had been subjected to something akin to the obsessive make-over staged by Scottie, at the hands of the Hollywood studios that made her a star. Vertigo is about cajoling an illusion into existence—a process from which there is no way out.