Thriving in Adversity

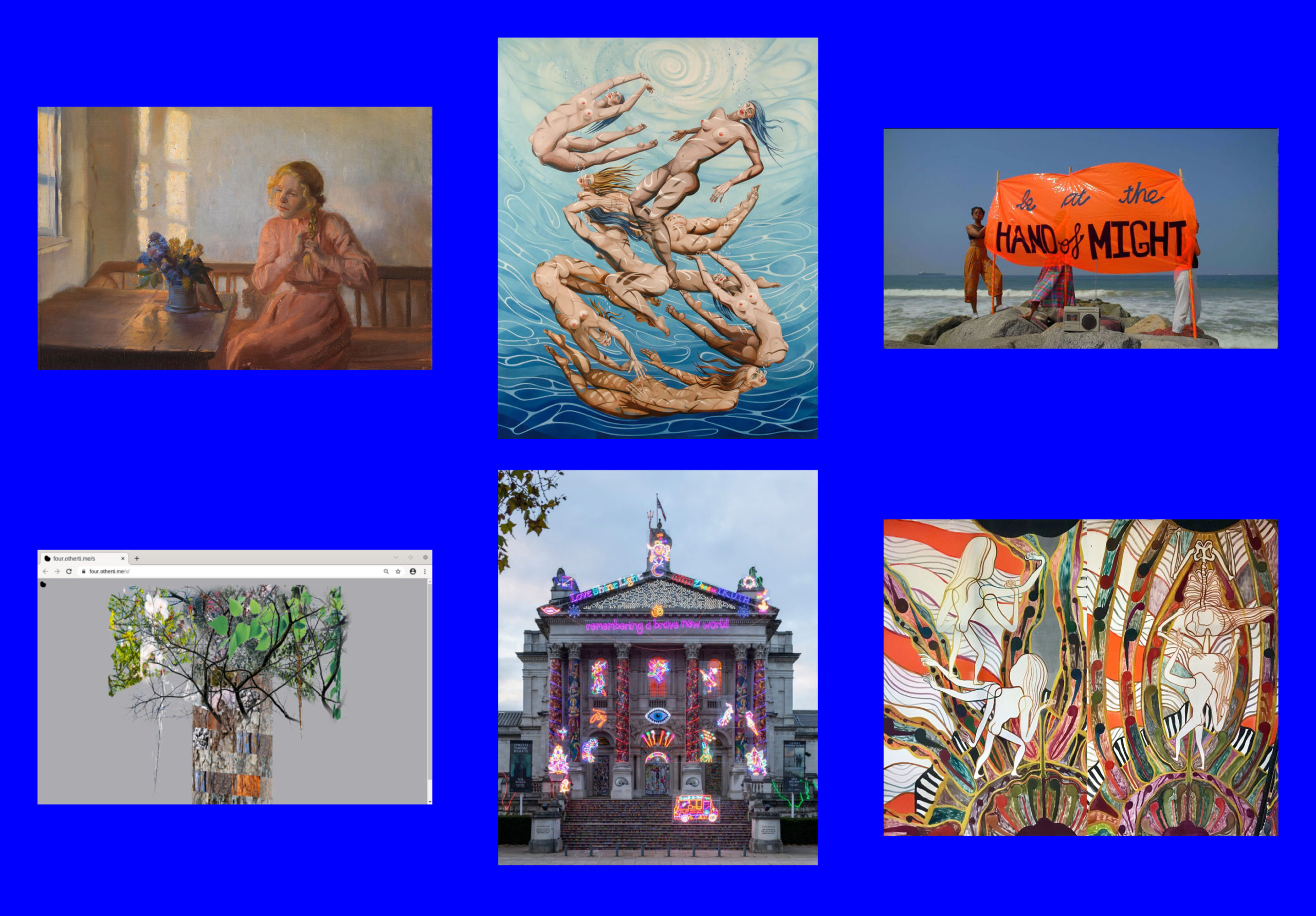

Emma Talbot

Talbot had some massive shows this year: the Max Mara Art prize; Ghost Call at DCA Dundee and When Screens Break at Eastside Projects, all while keeping calm and present despite this year’s many disruptions. She self-taught during the lockdown, developing drawings into beautiful, moving, dystopian animations. They rank as one of the most exciting artistic responses to this strange year. Her new work embodies this year’s themes, too: grounding, re-rooting, grieving, singing, community, environment, yoga, spirituality, mobility and an uncertain future. Lastly, she has continued to be supportive, involved and generous to fellow artists, giving time to podcasts, new ventures and online shows. —Chosen by Emma Cousin, multi-disciplinary artist with a focus on figurative painting

Bastide is a true web artist. During the lockdowns he released pages on two sites. Every day was a surprise, visually and technically; and every day it went deeper and deeper into what you can do with code and with the world wide web. I think his recent work showed people that there’s more you can do online than complaining about being online. —Olia Lialina, film and new media critic; pioneer of net art

Anna Ancher

In the long dark grey isolation that has been this year, Ancher can capture a sunbeam on a window sill and make me feel that “maybe it’s not time to kick the bucket just yet”. She was part of the Danish artist group Skagenmalerne and active at the turn of the century. Her domestic scenes brought me through the everyday struggles of 2020, capturing female subjects and labour in beautiful colours. I keep a special folder on my phone with close-up details of her paintings that were on show at SMK here in Copenhagen just before lockdown, and the colours are just…the shit that gets you through this shit… —Emilia Bergmark, visual artist living and working in Malmö and Copenhagen

Caroline Coon

It’s mad to think that the paintings I saw stacked three deep in Coon’s house turned out to be the most vital art of 2020. Some of those paintings are ten, twenty, thirty years old, but every single one is fresh and brave and relevant. All her life, it’s been: “You can’t paint that”; “you can’t show here”. Caroline has been vilified and rejected. You can go two ways when that happens: either cave in and find something else to do, or stick two fingers up and crack on. Thank fuck, she’s not the sort to comply. I admire how she’s fixated on the future—how it’s always the next painting that really matters. She says she won’t stop until she’s made the perfect painting. And I believe her. —Justin Hammond, co-founder of independent exhibition space J Hammond Projects

“Raphael Bastide’s recent work showed people that there’s more you can do online than complaining about being online” —Olia Lialina

Adam Farah

Farah is a storyteller, time collector and historian who weaves magic—whether the medium be moving image, Instagram stories, permanent posts, installation, sculpture or drawing. I’ve been a long-time admirer of their work but this year, whilst holed up in my flat or studio feeling restless and lonely, I found myself increasingly drawn into their world. Unlike most contemporary art which is fitted for the gallery, Farah’s practice happily exists outside the confines of indoor space and, luckily for us, lives in real time. A particularly wonderful element of their work, especially if you’re at home stuck, is the fact that Farah takes you outside. Using a mini action camera and or mobile phone to document their journeys, viewers are generously taken on meditative, essayistic observations of London and depending on the trip, audiences are sometimes treated to commentary and insight by Farah and their accompanying irl guest about the locations they move through. —Zadie Xa, Canadian artist exploring identity, desire, Korean mythology and personal fantasy

Cauleen Smith

Smith is an LA-based interdisciplinary artist whose experimental practice and vision for radical utopias inspire us to disrupt our everyday. Her COVID MANIFESTO—a project curated by The Showroom in collaboration with CIRCA on the Piccadilly Lights this November—offered us a timely insight into an individual’s intimate experience as shared through social media. The work is a powerful, politically charged reminder of the aesthetic significance of transient items in our daily routine; a storytelling that holds a mirror up to society, one daily pronouncement at a time. —Elvira Dyangani Ose, director and chief curator, The Showroom, London

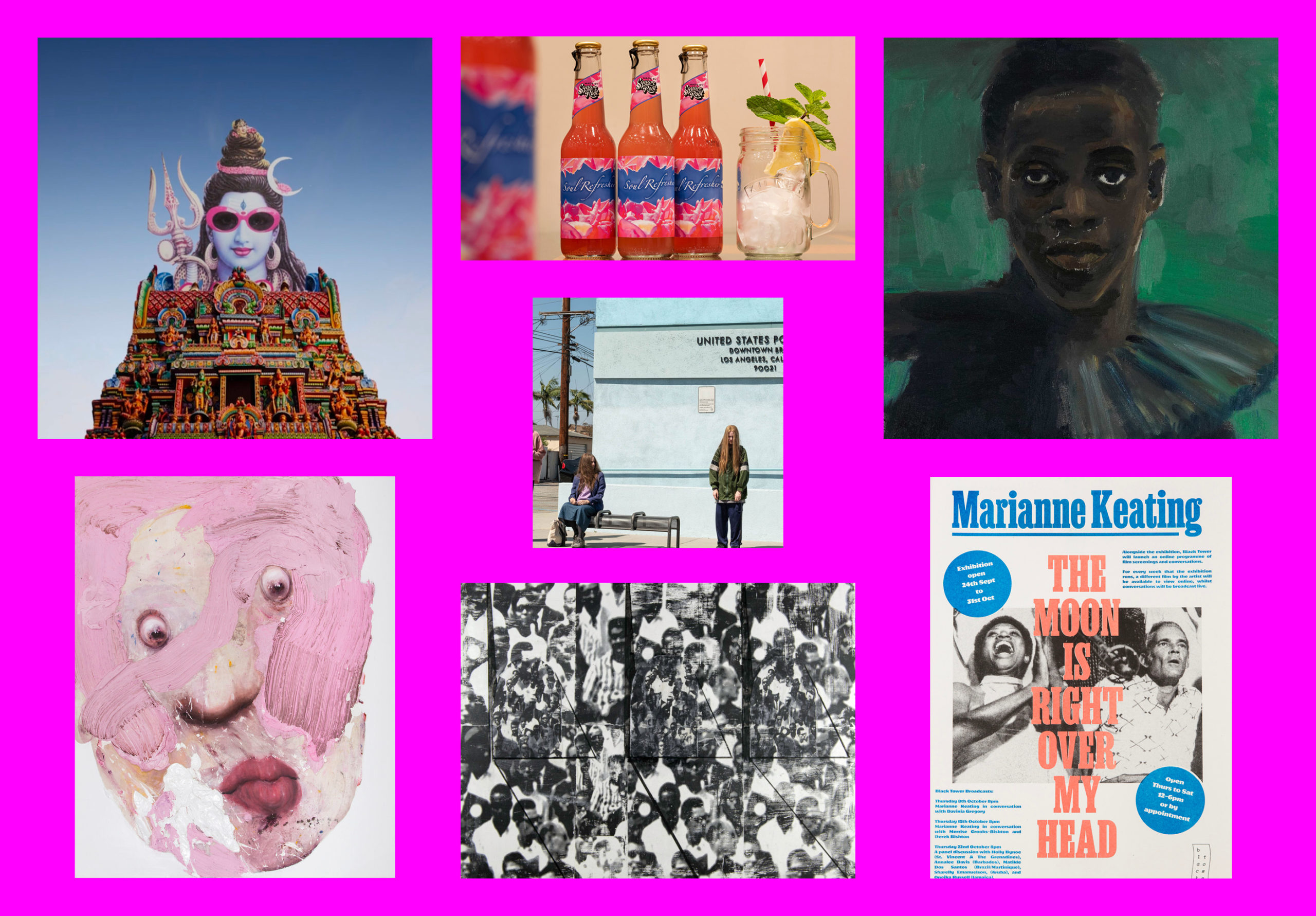

Chila Kumari Singh Burman

I think this was the work that we all needed at the end of this year! And that’s what I love about it. In a year when access to art has been so restricted and virtual, Burman’s phantasmagoria of light, that coincided with Diwali, was so generous and uplifting. It’s stunning. It is wonderful to see an artist that is able to convey the complexity and multilayered-ness of their inspirations (Hindu mythology, Bollywood, autobiography and colonial histories) and is still able to create a work that is a magical celebration of her culture. I’m totally in awe of her scope, vision and glittering boldness. —Lindsey Mendick, British artist working with sculpture and ceramics

Art as Activism

Lauren Halsey

On top of a beautiful blockbuster show earlier this year celebrating the aesthetics of her native South Central LA, Halsey has been tirelessly spearheading her Summaeverythang Community Center project—dedicated to “the empowerment and transcendence of Black and brown folks socio-politically and economically, intellectually and artistically.” Since the outbreak of Covid-19, the project has focused on packing and distributing hundreds of boxes of organic produce to residents of South LA and Watts at no cost. Halsey leads by example, showing what it means to truly serve one’s community—and inspiring us all to use direct action to bridge the gaps between art and values. —Gray Wielebinski, American artist working in print, video, performance, sound, sculpture, and installation

Cian Dayrit

Dayrit’s practice is one that we find compelling: he charts an emancipatory approach through collaborative textile-based works and counter-mapping workshops, as well as sculpture and painting. He is currently producing a large scale project for the 13th Gwangju Biennale which is part of his continued commitment to addressing colonial violence, resource extraction and military repression in the Philippines, and anti-imperial struggles toward self-determination.” —Defne Ayas and Natasha Ginwala, co-artistic directors of the Gwangju Biennale

Gabrielle Goliath

Goliath is an artist I’ve discovered only recently, but I find her series of work This song is for…deeply impactful. Harrowing, beautiful, and formally complicated the videos centre around incredible musical performances, that speak to all sorts of trauma, repetition, stasis and grief. It has been made over many years with a group of women who have survived rape—experiences of violence and living with trauma that are so relevant in this year, with the rise in domestic abuse being called the “shadow pandemic” by the WHO. —Tessa Giblin, director of Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh

“Halsey leads by example, inspiring us all to use direct action to bridge the gaps between art and values” —Gray Wielebinski

Arthur Jafa

Jafa’s Love is the Message, The Message is Death is a seven-minute video work I encountered two years ago. I sat riveted with swelling emotion as the film looped. This year, 2020, at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests, I immediately returned to this work in my mind. I began to long for a way it could be shared more widely while we all sheltered in place. To my delight, a host of museums around the world streamed the film simultaneously on loop. It was a rare moment when the activisitic potential of a work of art materialised in a moment of great urgency. —Derek Fordjour, interdisciplinary artist of Ghanaian heritage exploring race and inequality within American identity

Steve McQueen

I nominate McQueen for his powerful approach to humanity and politics, as seen in his Year 3 project at Tate Britain and Small Axe series of films. Through his lens we see crucially important issues and we are altered and bettered. Through each decision in his direction he leads the viewer to understand through compassion and observation. 76,000 Year 3 pupils are our future but what are we teaching them? Through deft handling McQueen shines a light on injustice and systemic issues that can no longer be ignored without us confronting our complicity. —Stacie McCormick artist and founder of Unit 1 Gallery-Workshop

My first urge was towards artists like Frida Orupabo or Kandis Williams, but I think Steve McQueen’s Small Axe films are the most important artworks to emerge from 2020. His constant awareness when depicting violence towards people of colour in Britain made them so visceral that I regularly had to take breaks from watching because it was so upsetting. Growing up in London, All Saints Road was a notoriously ‘dangerous’ street. McQueen’s films made me realise that this ‘knowledge’—and assumptions like it—were utterly racist and driven by a white supremacist system. He demonstrates how the Windrush scandal was brewing from day one. However, I feel the sympathy, humanity and beauty of McQueen’s films are truly having an effect on Britain. Relatives of mine in their seventies and nineties, who I would never, ever describe as woke, were recommending the first episode. For me, that alone is a sign of the truly significant change of understanding that culture can catalyse. —Francesca Gavin, London-based art writer and curator

Grace Ndiritu

“My art is an attempt to give back what has been taken from those who lack power: their dignity”, Ndiritu says. We must consider the context of her early work especially, for its brave use of the body, political rhetoric and the (lack of) space still occupied by Black women artists in Britain and elsewhere. Ndiritu’s work continues to propose non-rational and atypical methodologies such as shamanism as she reinvigorates notions of representation, shared and imagined histories, atmospheres of eroticism and cultural fetish. At a time where violence, conflict and social injustice have expanded across the world, Ndiritu is committed to collective healing—starting from the ultimate arena of outward reflection: the museum and exhibition space. —Emmanuel Balogun, London-based writer and researcher

Breaking New Ground

Rottingdean Bazaar

The duo’s work is humorous, meticulous, clever, beautiful, arresting, silly, inspiring and, above all, crashes through the hierarchies and boundaries of art, fashion, styling, photography and advertising. And they use some of my favourite media in their works: socks, pubes and themselves! In a year where most of our art came through the screen, it’s great to be stopped in your scrolling tracks by arresting and memorable images. —Paul Kindersley, queer performance and video artist represented by Belmacz

Fabrice Monteiro

I just discovered Monteiro’s Prophecy series of photographs this year. So powerful. A beautiful blend of African and global. Right up my visual alley! —Billie Zangewa, Malawi-born artist using embroidery to explore the political dimensions of everyday life

Jewyo Rhii

At the Korean Cultural Centre UK, we have celebrated Rhii as our own artist of the year. Her installations challenge the idea of what an exhibition can be—whether it’s a studio space, performance setting, and/or archive. Perhaps most significantly, Jewyo’s practice asserts the importance of collaboration, and despite the challenges posed by the pandemic this year, she has continued to extend her own opportunities to involve younger, emerging artists. This kind of support certainly warrants a nomination! —Jaemin Cha, curator of visual arts at the Korean Cultural Centre UK

Nick Paton

Paton’s work is very different to mine. He makes curious, thoughtful sculptures from clay, bronze, rope and wood. His mischievous titles are very honest and often make me laugh; Tic Tac Foe, Slick Servant Appears, Elephant Weighting. He is a great example of someone who adds without describing when titling. —Jessie Makinson, London-based artist known for her surreal depictions of the female figure

“Rottingdean Bazaar’s work is humorous, meticulous, clever, beautiful, arresting, silly, inspiring” —Paul Kindersley

Leena Similu, aka Yaya Situation

British born, Similu works from Silverlake, Los Angeles, making ceramics inspired by her Cameroonian heritage. She is something of a Renaissance woman: spending the first part of her adult life as a successful fashion designer before moving seamlessly into ceramics five years ago, with 2020 shows in LA and Portland. Pre-Covid she co-curated The Chronicles of LA with her husband James Mountford. It’s an immersive pop-up experience, featuring artists, designers, performers and musicians. She is always at the vanguard of everything she does and has been a great inspiration to me. —Polly Morgan, self-taught artist working with taxidermy, concrete and polyurethane

Haroon Mirza

A young artist whose work is getting more impressive year on year. He was a bright star at the Lahore Biennial in February. Seemingly endlessly inventive and experimental, he is confident in his collaborations as well as in his own work. —Jonathan Watkins, Director of Ikon Gallery, Birmingham

Issy Wood

Wood’s work continues to captivate and excite me. Depicting, often with humour, various objects and people we somehow recognise but yet feel strange and absurd. Wood’s painting technique is just so good, as well as her tasteful, intelligent way of choosing elements and organising them in an image. I’ve mentioned her name quite a few times this year in conversations, as her work has left an imprint on my mind, something I can’t fully figure out. Also, check out her music! —Oda Iselin Sønderland, Norwegian watercolour painter

Ronan McKenzie

Ronan’s skills as a photographer are evident in the rich tonal palette of her images, which appear in contexts as diverse as brand campaigns, high end fashion magazines, billboard art projects and international photography festivals. Evident, too, in her images is her sensitive connection with her subjects and her collaborative, multidisciplinary spirit. Combined with the work ethic that saw her launch Selasi, a collection of handmade clothing during lockdown, it is no surprise that she has rounded off this dispiriting year by opening her own project space in North London. HOME includes affordable studios, beautifully designed and lit exhibition spaces, and a library rich with literary and creative material honouring the Black experience. Proudly artist-led, HOME aims to present work by talented artists from underrepresented communities as well as affording opportunities for learning and growth. —Lillian Wilkie, London-based artist, publisher and teacher; founder of book fair Hypertext

Andrea Long Chu

I think everyone should read Females by Andrea Long Chu. I was out of breath after finishing this book. Punchy, extremely funny and serious, Chu lays out an incredible framework that scrutinises femaleness and gender performance. Drawing from Valerie Solanas’ SCUM Manifesto, Chu revisits Solanas’ claim that men are women and women are men in order to critique the sexual landscape today. From performance art to incels and porn, Chu cuts through them with fire and wisdom. I think this text and writer are revolutionary. It should be mandatory reading and can’t wait for what Chu does, says, thinks next. —Bruno Zhu, Portuguese artist working across photography, installation and sculpture; founder of art space A Maior

“From performance art to incels and porn, Chu cuts through them with fire and wisdom. I think this text and writer are revolutionary” —Bruno Zhu

Michael Armitage

The historical and cultural issues Armitage approaches find an interesting balance in his choice of material: Lubugo Barkcloth. His paintings communicate not only via the visual iconography of certain locations in Africa, but also from the process and materials themselves, where memory plays an important role. His work is a document of sorts, collecting stories and myths unbeknownst to many of us who have no ties to Africa. It is in the particularity of his chosen geographies where I find the greatest connection with my own work. —Jhonatan Pulido, Colombian painter exploring memory, place and escapism

Clara Ursitti

I love the subtlety of Ursitti’s work—so much that it often goes unnoticed. I once went to a screening where she was scheduled to perform, though, at the time, I didn’t even realise it was happening. The only thing that struck me as unusual about the situation were the 25 elderly women who attended the event, arriving at the last moment before the screening began to sit in the front row. I assumed they were someone’s aunts, but still couldn’t understand why there were so many of them. There was also the occasional strong waft of Dior Poison. After the event, I learned that these women were performing as part of one of Ursitti’s “scent interventions”, a work titled Poison is My Potion (2013). The work involves a great deal of research—Ursitti often develops her own “scents”—but also has a strong underlying sense of humour. —Erica Eyres, Canadian artist known for her comedic films, drawings and ceramics

Showstoppers

Chila Kumari Singh Burman

I visited Tate Britain after the second lockdown, a chance to see some art in person after what has felt like an eternity. When Burman’s Tate commission launched (coinciding with Diwali), I had seen so much of the installation on Instagram, but being based in the North I’d not had the chance to see it in the flesh. I reached the gallery on a gloomy afternoon; it really was something else to be able to witness the spectacle in-person. Multifaceted, meaningful, and also fun and accessible, it was overwhelming (in a good way). Burman’s Remembering a Brave New World is the celebratory and hopeful work we all need during these tough times. —Lydia Blakeley, artist featured on the cover of Elephant Issue 41; winner of the FBA Futures Art Prize 2020

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s powerful portraits are not only painted with so much skill but I also love the emotional atmosphere they give off. She has a beautiful sensibility and an incredible use of colour and light in her work. Her current solo exhibition at Tate Britain is well deserved, I feel lucky to have had the privilege to view it first hand. —Seana Gavin, London-based artist working with vintage photographic material

Kandis Williams

Her Instagram stories got me through lockdown unlike any other and the Cassandra Course programme is a real sign of community/artist-run teaching that can benefit all. She has her first institutional solo show currently up at ICA VCU and her new large-scale collage works as part of the Hammer’s Made in LA show are phenomenal. It was a privilege to see them from draft to completion and I can’t wait to visit in person (Covid permitting)—and hopefully hang one in my home one day! —Rhea Dillon, artist and writer

Miranda July

I feel the need to give artist and writer Miranda July a shout out for her terrific new film Kajillionare. With an expert script, subtle direction and a great cast, July put together a film I immediately wanted to watch for a second time the moment it ended. —Hernan Bas, American painter known for his figurative work inspired by nineteenth-century culture

“Zahedi’s latest project wove together the infrastructural legacy of the site with the spiritual journey of grief, and left a lasting impact on me” —Paul Purgas

Farrokh Mhadavi

Earlier this year, Mhadavi had a show at V-Gallery in Iran which blew my mind. The work discusses the human condition when people are forced into different situations. In his recent portraits, eyes are prominent—gazing at you with fear and dread. He believes eyes can represent anyone’s sensations or feelings. He uses his own particular shade of pink and utilises this shade based on his own understanding of colour. He shapes the works by destroying them several times until he finds out what it is he’s been looking for. If some parts of the painting are not adding to the work, he cuts them out and leaves the cutouts on his studio floor. He sometimes then uses them for his installations, as he did at Palais de Tokyo last year. —Orkideh Torabi, Iranian painter living in Chicago; her work resituates the dynamics of Iran’s patriarchy

Marianne Keating

I’ve chosen Keating for her exhibition The Moon is Right Over My Head at Black Tower Projects. Marianne is an amazing artist and researcher, and I have seen this project grow and develop over the last few years. The exhibition brought three films together which examine the legacy of the Irish diaspora’s migration to Jamaica, and faced the viewer with important questions about which histories form a part of the dominant narrative. The show was timely, and demonstrated what rigorous artist-led research can do. —Felicity Hammond, British artist working across photography and installation, with a focus on the political contradictions of the urban landscape

Abbas Zahedi

Over the last year I have been grateful to encounter three projects by Zahedi: a sensitive and powerful performance at Spike Island featuring animation, dense sonics and spoken word; his socially centred Soul Refresher commission for the Brent Biennial; and a solo exhibition at South London Gallery’s fire station this summer. The latter wove together the infrastructural legacy of the site with the spiritual journey of grief through a poetic assembly of utilities and ritual artefacts. All three have left a lasting impact on me. I continue to return to them mentally as if still subconsciously unravelling their message, drawing threads and connections between them. —Paul Purgas, artist and musician working with sound, performance and installation

This year, it’s as if I’ve felt everything through both ends of a telescope simultaneously. My emotional response to art has been heightened. I don’t have a favourite artist, but the work that resonated with me the most at a very particular moment in August, when we could go to galleries again, was Abbas Zahedi’s How to Make a How from a Why? at South London Gallery. The show focused on lamentation rites and other moments of literal and metaphysical exit, with ideas articulated through a series of unusually and delicately interconnected objects. It was an intense balancing act between personal and social histories, revealing how people come together within modes of resistance and release. To me, at that moment, it felt like walking into a poem that was happening all at once. —Rosie Cooper, Head of Exhibitions at the De La Warr Pavilion, an arts centre in an iconic modernist building by the sea

In Memoriam

Emma Amos

In May, the artist Emma Amos died. I find it hard to say anything summing her up, so I won’t. Her work has been at the back of my mind throughout the year: it has slipped about like a new calf, always wet, rangy, and unexpected. In particular I think of her work Josephine and the Ostrich (1984), a diptych of monotype, scribbled pastels, collage, and smeared ink, and the very different Dream Girl with Woven Camisole (1978), and etching and silkscreen print. I love the difference in her work. —Jamie Crewe, British multidisciplinary artist, and recipient of one of the ten Turner Prize bursaries from Tate Britain in 2020

Siah Armajani

Armajani, who passed away this year, was an artist whose work was resolutely civic-minded and ravishing in equal measure, who defied the identity politics of his time (and ours) and was as influenced by American transcendentalism as he was Twelver Shi’ism. Thankfully, he lived to see a major retrospective of his work presented at the Walker in Minneapolis in 2018 and The Met in NY in 2019. —Slavs and Tatars, art collective with a practice based on three activities: exhibitions, books and lecture-performances