Snapshot is a weekly series that zooms in on a single photograph to explore the context of an image, the conditions it is created within and its wider cultural impact.

It is often easy to forget that the medium of photography is little over 200 years old. In that time, a labour-intensive and somewhat volatile process of exposure, development and fixing has become an instantaneous action enjoyed by the masses, with millions of megapixel image files being produced and transmitted every day.

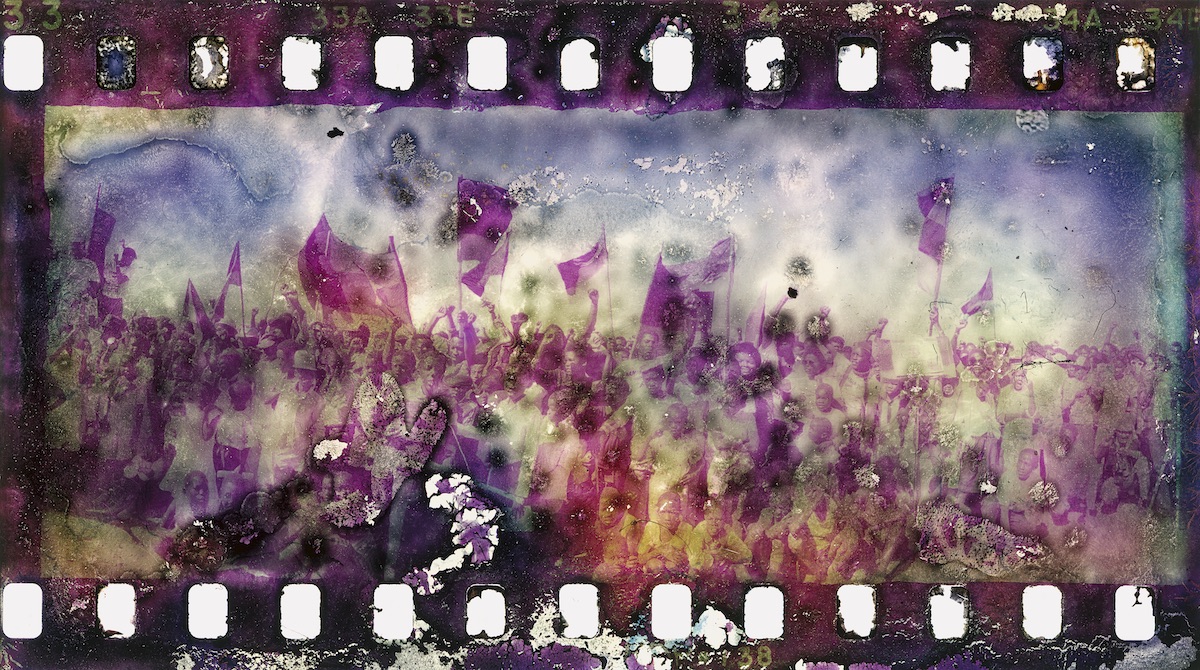

While examining photojournalist Gideon Mendel’s rescanned, corroded negative of a celebratory rally in Namibia, some might not equate the punched-out notches and slippery, bleeding pigments with the very physical act of taking a photograph. It is fair to say that at least one generation has now grown up without an inherent familiarity with “analogue” camera technologies, where even physical prints are usually the result of digital production methods.

This was not the case for Mendel, who, during the 1980s, was documenting the realities of the fight against apartheid. He was present on day that Sam Nujoma

returned after thirty years in exile, to roaring crowds. The leader of the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO

) went on to become the newly independent nation’s first president, sworn in on 21 March 1990.

“The images still carry the power of those remarkable scenes, yet their corruption and damage seem to magnify that energy”

That same year Mendel left a box of his outtakes chronicling not only Nujoma’s return, but other events of activism and protest, in storage in Johannesburg. He promptly forgot about them, only to rediscover the water-damaged and mouldy negatives two decades later. “I was struck by the fact that the interventions that overlay my original photographs are happenstance, completely random impacts of time and water,” Mendel explains in his statement for the subsequent project Damage: A Testament to Faded Memory, which was nominated for the Prix Pictet in 2019. He continues, “The images still carry the power of those remarkable scenes I documented all those years ago, yet their corruption and damage seem to magnify that energy.”

Through the passage of time and its effects, Mendel’s photo now holds the fluidity of a memory, where once crystal-clear outlines of faces and raised flags have become somewhat clouded and obscured. The new, blemished image could also point to the inevitable complexities that follow a moment of jubilation. Mendel recalls this revolutionary period as a time of “hope and tragedy”, and has begun to grapple with the conceptual ideas surrounding the word “process”.

He has come to understand that he experienced many intense and traumatic events at this point in his career, but chose not to take the time to process them psychologically: “Like these negatives, I left them packed away.” Until recently, the act of taking your as-yet unseen reel of images to “be processed” (or indeed doing it yourself) was an act of time and labour. In the new digital era this period of preliminary reflection has been arguably eradicated, for better or worse.

In this particular case, a new iteration of a 30-year-old photo offers Mendel the chance to reckon with his own practice and the legacy of these events, while allowing viewers the space and time to consider what an image really means. He shows that it is not merely the record of a subject, but an ever-changing vision of history, experience and memory.

Damage: A Testament to Faded Memory

On show as part of Hope, a virtual exhibition mounted by Prix Pictet and the V&A

VISIT WEBSITE