How and why we define something as “feminist” is multi-faceted quandary. For starters, the very word caused many to balk until relatively recently, with the reductive image of man-hating militant activists being used and abused by many. Nowadays the term has been firmly etched in pop culture, with everything from start-up CEO mantras to cosmetics brands rushing to align themselves with female empowerment. This co-opting of the term has left plenty of us asking exactly what being a feminist means (for surely there is more than one reading) and speculating on an unending list of questions: Can feminism exist without intersectionality? Are “women only” spaces and groupings empowering or problematic? Is an act or practice defined as feminist simply because a woman is doing it?

This last question was at the forefront of my mind while visiting Charlotte Perriand: Inventing A New World at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. This enormous exhibition, which commemorates twenty years since her death, is the first to take over the entire Frank Gehry-conceived space and seeks to reassess the legacy of an exceptional architect and designer whose work has too-often been eclipsed by her relationship to famous modernist men—from Le Corbusier

to Jean Prouvé.

“Her commitment to conceiving a more egalitarian world has contributed to our ongoing quest for equality of the sexes”

Perriand has been subject to many of the traps that often befall successful creative women. For example, she is better known for her furniture design than her architecture, which is undeniably due to the historical association between women, domesticity and the applied arts, while architecture, which is so often defined by grand gestures and utopian ideologies, still remain predominantly the purview of men. She is also lumped in with two other innovators, Eileen Gray and Ray Eames, largely due to gender as opposed to actual professional affiliation, which can seem pretty eye-rollingly reductive in this day and age.

What is more, the issue of Perriand’s feminist credentials are often discussed when considering her legacy. For plenty of female innovators, this is an inescapable form of scrutiny. It has been regularly noted, for instance, that she did not align herself with the movement of the period and hated to be labelled as a “woman designer”—something that plenty of people take issue with today, as mentioning gender belittles a particular profession or practice, as if it is somehow a departure from the norm.

People have also asked whether she “lifted other women up” (there was no direct answer from the curators during my visit to the show), as the idea of aiding and supporting other women is one of the primary pillars of feminism, but when you break it down it can be a divisive statement. You have to ask: Can someone be a feminist if they are only out for themselves? Or is it in fact a problematic symptom of the patriarchy that women are expected to shoulder the burden; to nurture and support, while men are not generally held to the same standard? More questions follow: can something only be feminist if the creator declares it? Is the trend of “performing” feminist actions dangerously reductive?

Charlotte Perriand, René Herbst, Louis Sognot – Maison du Jeune Homme, Exposition universelle de Bruxelles, 1935. Reconstitution 2019 avec la participation de Cassina &Sice Previt ainsi que le conseil scientifique de Arthur Ruegg – Vue de l’installation, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris – 2 Octobre 2019 – 20 Février 2020. Crédits artistes : © F.L.C. / Adagp, Paris, 2019 ; © Adagp, Paris, 2019 Crédit photo : © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage

Of course, when viewing an exhibition about Perriand, who died in 1999, you also have to be mindful of the historical lens, where carving out a successful career as a woman was radical within itself. She might not have used the F-word, but to my mind her vision for contemporary living certainly contributed to a recalibration of the private sphere, which went some way to emancipate the modern woman.

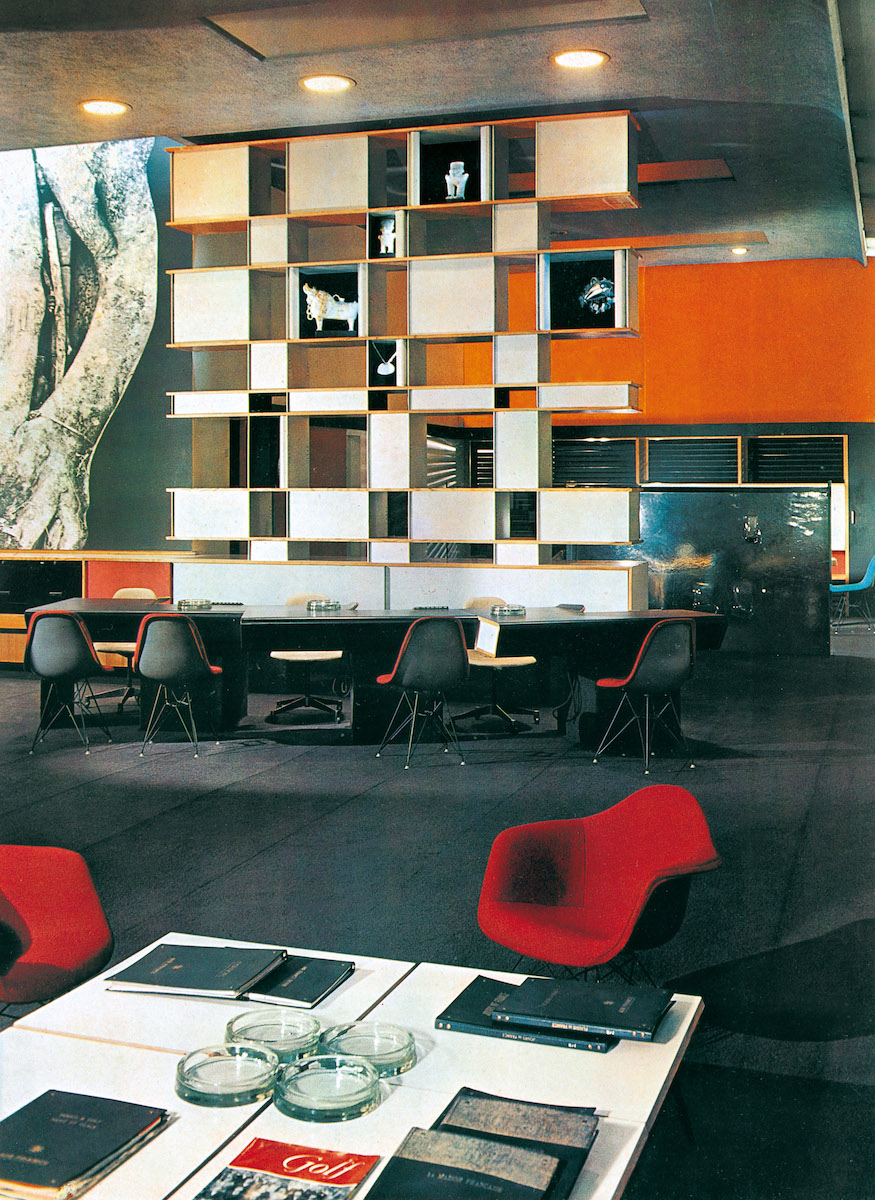

Her radical designs were ultimately holistic, all-encompassing blueprints that combined art, nature and an active lifestyle within a single dwelling. She brought down walls and demanded freedom of movement, meaning that women were no longer shut off in a kitchen and behind other closed doors, but could remain part of the action (even if they were still doing all the leg work). She always emphasized collective working; sought out new cultural insight and influence in Japan and Vietnam; and considered that the hierarchy of applied arts, fine art and design should be dismantled.

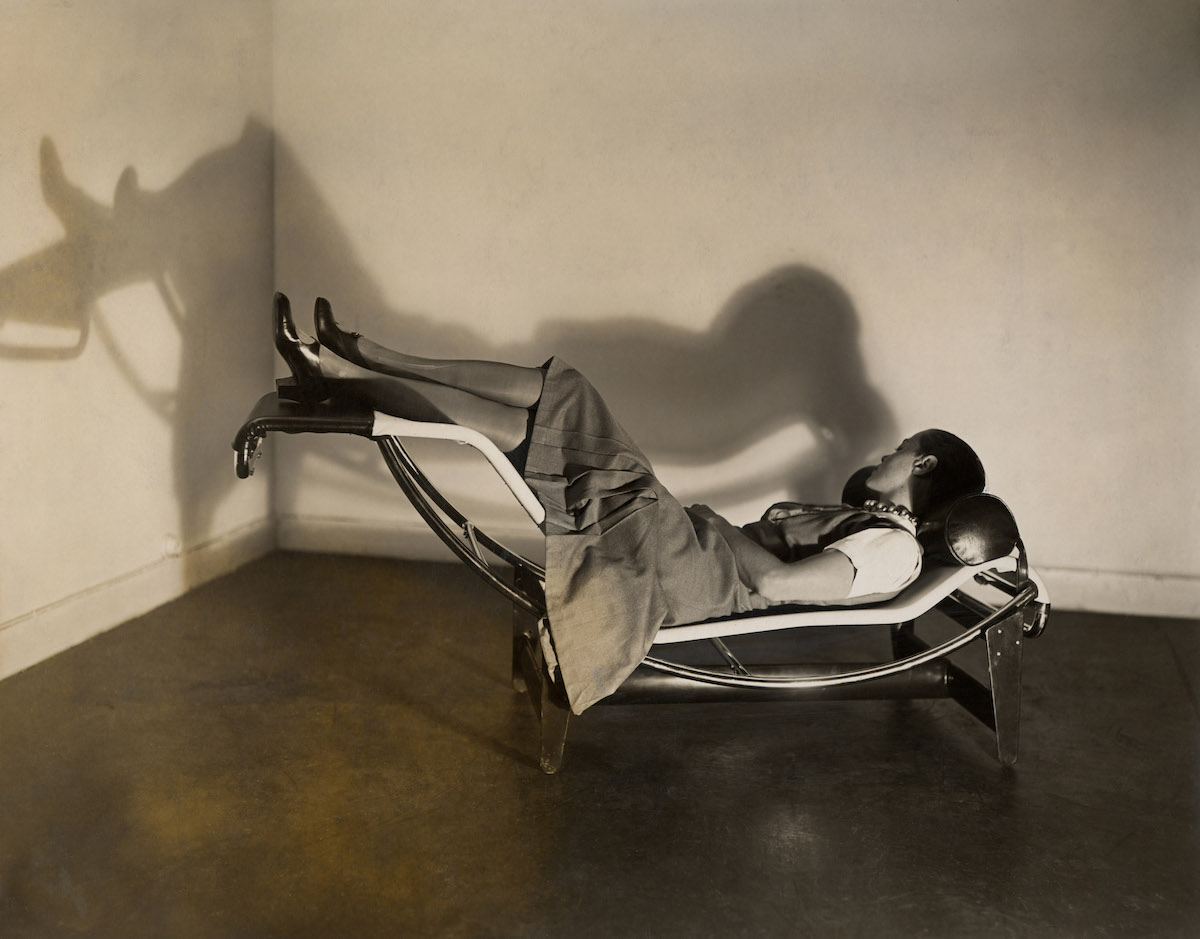

The LVF show brings together entire reimaginings of homes, an impressive archive of furniture and general ephemera to paint a portrait of a practice that still seems cutting-edge now. She designed a chaise longue that would have seemed pretty damn racy for women who were still confined to skirts; a ski lodge that looks like a space ship; and an entire resort in Les Arcs, which was imagined to be sympathetic to the surrounding mountains and used innovative modular architecture. Apparently, Perriand was so convinced that residents would love her new open-plan lifestyle that she was on call to personally convince any sceptical buyers.

“It is far too easy to try and put a label on Perriand, but she was always loath to define herself”

One of the most fascinating things about the exhibition is witnessing the sheer scope of her practice. Not only did she design things that upended traditional living standards, but she had the foresight and tenacity to demand a job from Le Corbusier (who had more than a mild chauvinist streak) and commission established artists like Fernand Léger to produce work for the homes she conceived.

This steadfast belief in her own worth is equal to any contemporary feminist trailblazer, and her commitment to conceiving a more egalitarian world has contributed to our ongoing quest for equality of the sexes, particularly in the domestic setting. It is far too easy to try and put a label on Perriand, but she was always loath to define herself, according to her daughter and exhibition co-curator Pernette Perriand-Barsac—finding any single occupation or premise rather reductive. She once stated, “The key thing for a woman is her freedom, her independence. Being at the top of what she is doing.” She made her own rules, and whether or not you impart the F-word, that is inspirational.

Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World

Until 24 February at Fondation Louis Vuitton

VISIT WEBSITE