Space is political. Whether it’s the virtual, the physical, or the metaphorical, the power of obtaining and retaining space should never be underestimated. Within the art world, this rings particularly true. Securing a studio, getting work into a gallery, or simply gaining visibility within a field ring-fenced by nepotism has long plagued artists, especially those of colour.

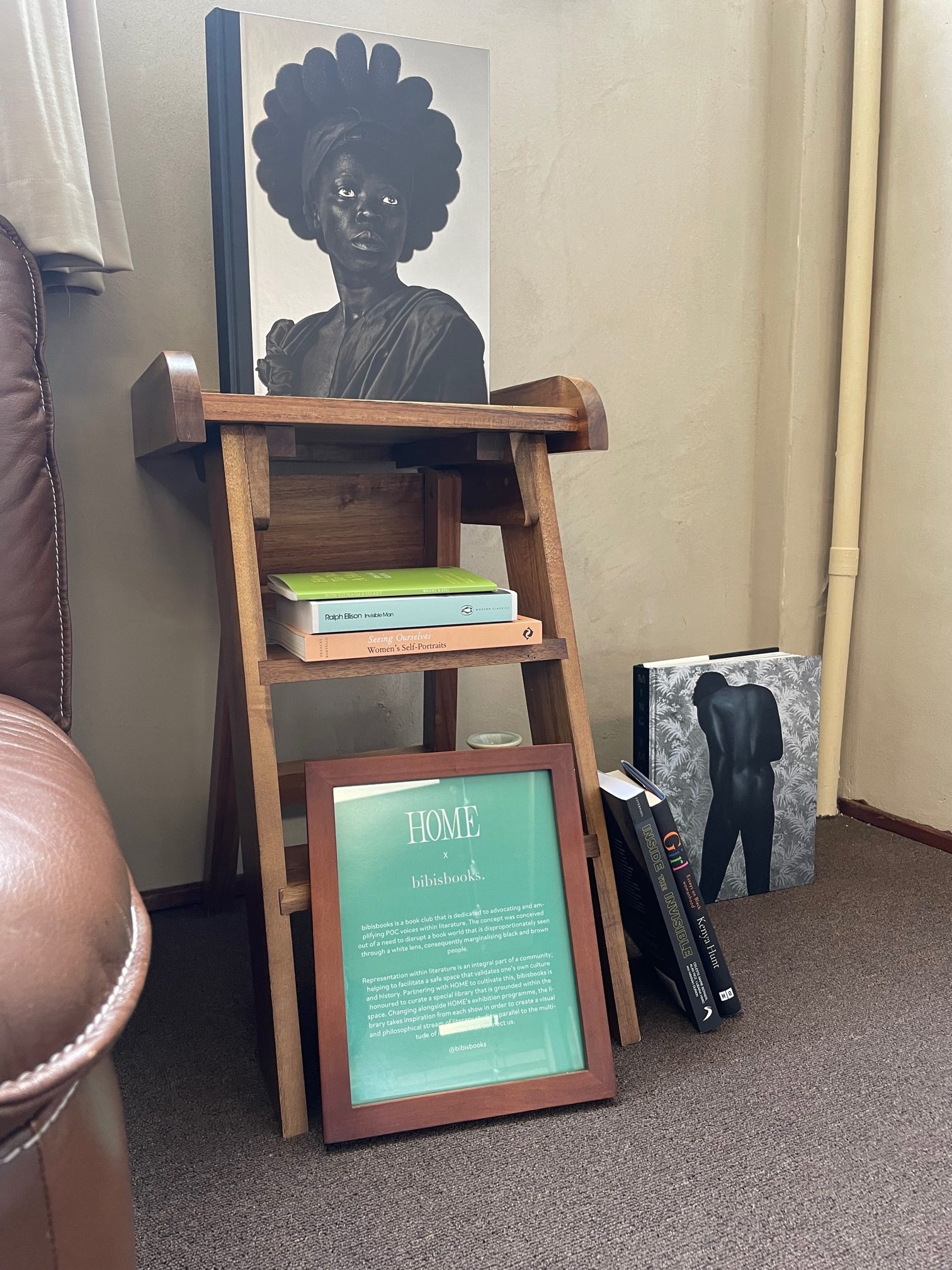

One of the newest examples is HOME, a multifunctional, artist-led creative space in Hornsey, North London, founded by Ronan Mckenzie. “Everything was intended to make people feel warm,” Mckenzie explains. “We have a beautiful clay plaster that is porous… so you feel an element of nature within the space.”

Light cascades through the windows, while notes of cinnamon and honey fill the air. Each design choice is deliberate, from the Aya Aromas candles, to the low hanging lights, intended to make visitors “feel held”. It is at once nostalgic, yet full of new possibilities.

Mckenzie wanted to create a place which could display more art from BIPOC people, particularly women. On seeing the Zanele Muholi exhibition at Tate Modern, she loved the work, but was critical of the space it inhabited. “It’s not enough for work to just be on the wall,” she argues. “Being in the Tate with all these white people looking at this very intimate work: how much of it are they taking in? To engage with a work is so different from viewing a work.”

She felt differently on seeing the artist’s work at Autograph, a publicly funded organisation based in Shoreditch, which has championed photography that explores issues of race, identity, representation, human rights and social justice since 1988.

“It felt more one-on-one,” she explains. “It feels different when a space is ten acres and you’re wandering around as one of a thousand. As one of ten, I can engage with something on a more personal level and take my time with it without being shifted around. Autograph is still a traditional gallery, but because I know there are Black people behind it, I feel more comfortable.”

“Being in the Tate with all these white people looking at this very intimate work: how much of it are they taking in?”

So how did she start her own gallery? Mckenzie explains that her commercial photography practice funded the creation of HOME. She believes money is the biggest obstacle to there being more Black-owned arts spaces in London.

“I have a job that pays for this, I don’t have any family I need to take care of,” she says. “I have freedom in some ways other people might not. I won’t even tell you how much money I put into this, but I could have bought houses. I don’t know many BIPOC people who have that money to spend.”

US institutions such as the Studio Museum Harlem, or the Underground Museum in LA were big inspirations for Mckenzie. That American lineage of Black-owned spaces isn’t mirrored in Britain. “It’s key to remember that there are five, six generations of Black people in America. Our story mainly begins with Windrush, so we have about 60 years. We haven’t had time to build that legacy.”

“A student could go through their whole three-year experience in an art school and never be taught by a person of colour”

Despite this deficit, Mckenzie recalls the Finsbury Park based Black-Art Gallery created in the 1980s. Started by former Black Panther Shakka Dedi and the Organisation for Black Art Advancement and Leisure Activities (OBAALA), The Black-Art Gallery was set up to spotlight the work of artists of African ancestry. Despite council funding and a huge audience footfall, the space shuttered after ten years, and is now part of Finsbury Park Trust.

The precarious nature of private and public funding means that longevity will always be a concern, but there are success stories. Gilane Tawadros, the founding director of the Institute of International Visual Arts (Iniva), explains that its creation was spearheaded by artists and intellectuals in 1994. The plan had been to build a ‘white-cube’ gallery space, but Tawadros quickly realised that fundraising for that would not be politically viable at the time: “We had to make an impact really quickly and think about survival from the beginning.”

When no gallery would show Yinka Shonibare’s Diary of a Victorian Dandy, it took over billboards at Oxford Circus. The work was seen by a million people. “My board meetings were Stuart Hall, Sarat Maharaj, Steve McQueen, Zarina Bhimji…” says Tawadros. “Artists were the driving force of the organisation”.

“We had to make an impact really quickly and think about survival from the beginning”

It was towards the end of Tawadros’ tenure that Iniva bought a plot of land at Rivington Place, and built what is now Autograph ABP (Iniva and Autograph shared the building until 2018, when Iniva relocated to Chelsea School of Arts). She explains that it was only once they had a physical space that they were able to secure the largest donation they had ever received.

Tawadros’ advice for those starting their own creative spaces is to be clear about the project’s intention. “Expect to be challenged and meet obstacles but to be agile and creative about finding solutions,” she advises. “One thing that came out of the punk/DIY movement is that you don’t have to wait for everything to be in place to make those interventions.”

This is what Bolanle Tajudeen did in conceiving her online platform Black Blossoms in 2015, while at University of the Arts London. “I never went to university to become an advocate for diversity and inclusion,” she says. “But you’re hit with the reality of racism having a long-term effect on your career, on your friends’ careers.”

“Autograph is still a traditional gallery, but because I know there are Black people behind it, I feel more comfortable”

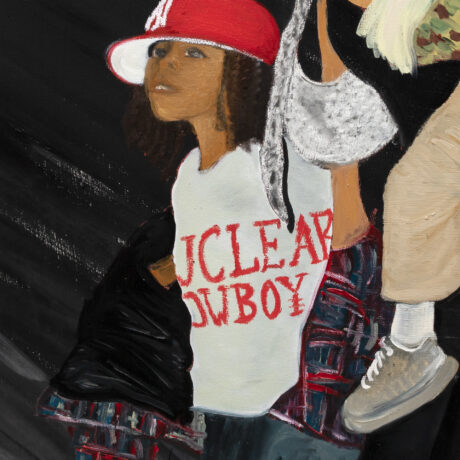

Tajudeen decided to create a space for people of colour, particularly women of colour, to share their creative visions. The platform grew from a deep respect for the BLK art movement of the 1980s, and Tajudeen wanted to create something similar. Black Blossoms incorporates an interactive public programme of panels, exhibitions and screenings, aiming to highlight artists who identify as Black women or non-binary people.

In 2020, she expanded the platform into Black Blossoms School of Art and Culture, which offers short courses that “decolonise, deconstruct and democratise” students’ creative learning. “All the lectures are from people of colour or of marginalised identities,” says Tajudeen. “It’s very likely that a student could go through their whole three-year experience in an art school and never be taught by a person of colour.”

Tajudeen stresses the importance of a democratic learning environment: “I’m always thinking, how do we make sure that all participants are heard equally and [that] they’re valued?” She encourages participants to share social-media handles and foster independent relationships. “We can have a senior curator from a really elite institution, and an art student,” she says. “They both have equal cultural capital.”

Anoushka Khandwala is a graphic designer, illustrator and writer practicing in London