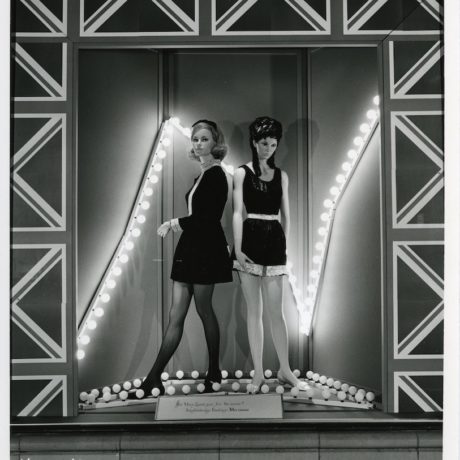

The Swinging Sixties remain a powerful, nostalgic vision of British life. The era is remembered as the moment when London fleetingly became the centre of the universe, thanks to a swathe of youth-centric creativity, from fashion and music to art and photography (for indeed they were considered separate entities back then). Images of waifish models populating Carnaby Street boutiques, and cool young musicians performing on Ready Steady Go!, endure over half a century later.

Of course, the realities are always more complex than the sanitised (not to mention rose-tinted) idea of a countercultural scene, and Lisa Tickner attempts to break down the somewhat homogenous narrative that surrounds the art and culture of the sixties in her book London’s New Scene. Rather than attempting an exhaustive survey, Tickner formulates a collection of focused, individual studies in the form of a film, a gallery, an exhibition, a book and a protest.

These touchstones underpin the transformational moments that allowed avant-garde to flourish, but Tickner doesn’t shy away from the grit and grime of the city. Her book is foregrounded by the rubble strewn streets that were still commonplace in post-war London, and further contextualised by the vice grip of slum landlords, who offered dilapidated bedsits to young artists in areas like Notting Hill in order to drive out longstanding tenants.

“The very idea of a ‘scene’ is flawed, where artists are shoehorned into a particular category to make their work seem more digestible”

The very idea of a “scene” is of course flawed. It is similar to the idea of artistic “movements” where artists are shoehorned into a particular category to make their work seem more digestible and marketable. Tickner reminds us of this fact throughout, particularly in her chapter discussing the relative merits and pitfalls of Ken Russell

’s Pop Goes The Easel, a production for the BBC’s Monitor.

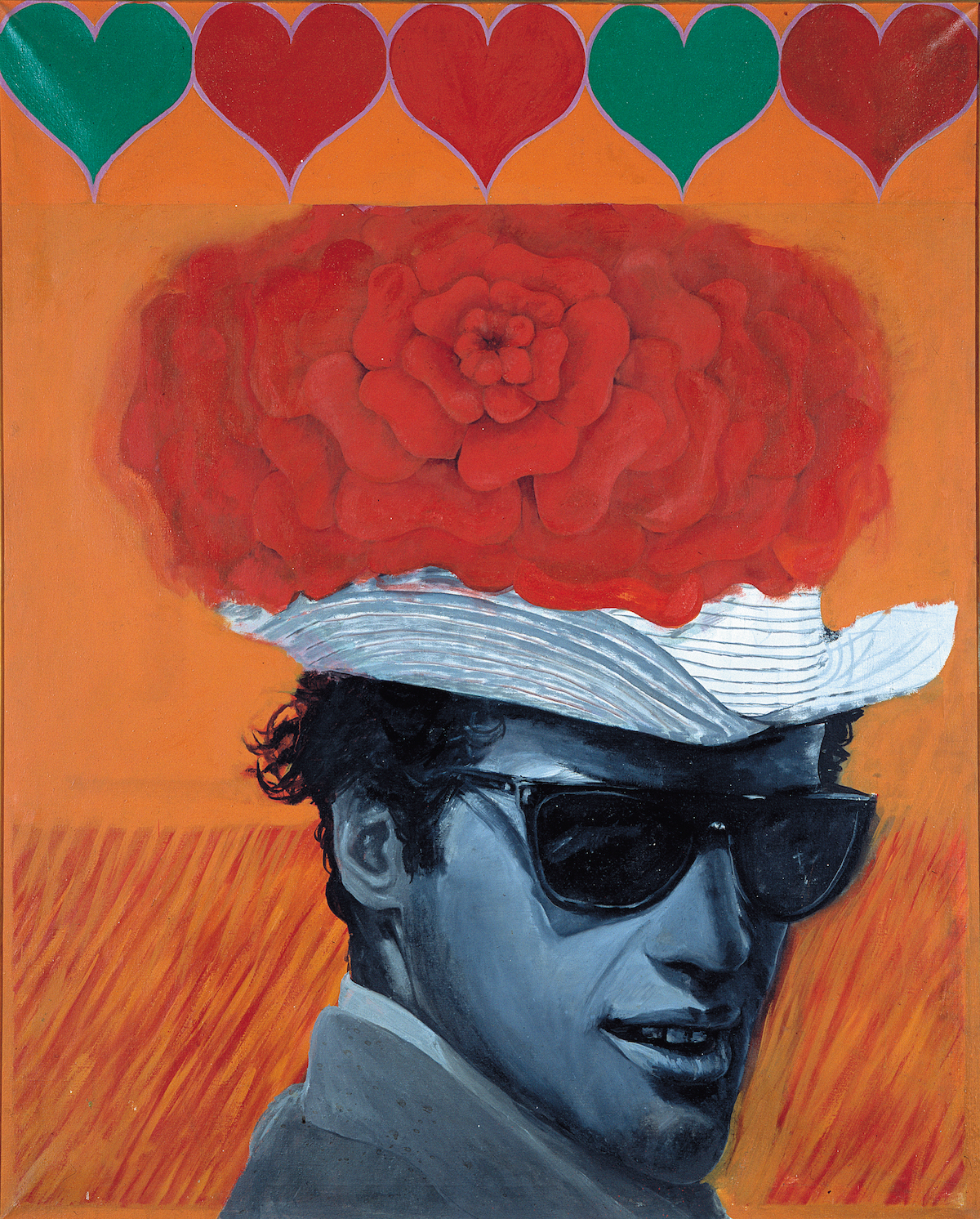

Using Peter Blake, Peter Phillips, Derek Boshier and Pauline Boty as his subjects, Russell created an art piece cum documentary that attempted to capture the essence of the British Pop Art movement. He used unconventional cuts, focus points and dream sequences in a manner that aped the artists’ work, while also succumbing to the appeal of personalities as opposed to exploring the art itself.

Tickner explains that this was particularly the case for Pauline Boty, a hugely talented artist who remains largely overlooked not only because she died tragically young, but because of the fact she was a woman. While Tickner grapples with the many ways that Boty was fetishized and infantalized in the film, she also refers to the absence of David Hockney, who was originally approached. Ultimately neither he or his work fitted into the flirtatious, heterosexual narrative Russell was gunning for, or the prescriptive definition of Pop Art, which Hockney himself eschewed.

Tickner continues to go into forensic detail in each of her chosen studies, reflecting on not only the direct art-world context, but the wider creative cross-overs that elevated artists and photographers to a state of celebrity. These included Antony Armstrong‑Jones (aka Lord Snowdon) and David Bailey’s candid snaps of artists at work, but more importantly hanging out at parties and private views at places like Kasmin Gallery, where the stuffy image of commercial galleries was upended.

She also explores the country’s wider socio-political climate and how it interrelated with the relatively small art scene, from irate audiences who complained about the BBC’s renewed interest in art that embraced American pop culture, to the Hornsey Art School Occupation. On 28 May 1968, students and staff led a six-week sit-in protesting the conditions of the school and its curriculum, which changed the face of arts education on a national level.

All of these threads are not woven into a single tapestry, but remain frayed and loosely held, intersecting and looping back on themselves. Tickner shows just how complicated the idea of a definitive “scene” remains. In quoting the curator Alan Solomon she points to the galleries, clubs, parties and friendships that form a nucleus from which creativity can be fostered, but she also alludes to a more purist view, that underpins the very concept of art production. It comes from Barnett Newman, the influential American artist and educator, who states, “There is no scene. The scene is the artist working in his studio; everything else depends on this.”

London’s New Scene, Art and Culture in the 1960s, by Lisa Tickner

Published by Yale Books, out 9 June

BUY NOW