Your new show at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London is your first solo exhibition at the gallery, following your presentation at Frieze Masters last year. Does this feel like an exciting opportunity to introduce your work to new audiences?

My paintings appeared at Frieze Masters last year as part of a dazzling collection of other works of art, the existence of which I had been aware of, but I had never before had the opportunity to observe them in a common physical space and time. Seeing my paintings there, in this new environment, compelled me to reacquaint myself with them. Now, as my solo show opens, I am hoping that there will be viewers who will find the reality of my paintings capable of filling in a hitherto empty gap or space in their imagination.

You trained in various forms of painting as a student, alongside abstract principles. How did this balance inform your practice?

Interestingly enough I first got into close contact with abstract painting at the very beginning of my professional studies in Pécs, Hungary in 1946 at the age of thirteen, when painter Ferenc Martyn took me on as a pupil. He had lived in Paris before for fifteen years and he was a member of the Abstraction-Creation artists’ group there. He issued me pencil drawings tasks which were mostly studies of nature.

Meanwhile I had the chance to see his abstract paintings and colourful spatial objects in his studio, works that I acknowledged as the art of the present moment, at the time. I understood and accepted that studying real-life spectacles and depicting them with lines, colours and forms is itself the road that leads to abstract creative work.

I considered myself a dedicated artist-to-be already at a very young age. Alongside secondary school I attended afternoon art classes together with other young people. In 1958, having completed my academic studies, I started making my first abstract paintings and India ink drawings. I tried and applied almost every mode of presentation that I felt like, or that I liked in other works of art, by continuously alternating styles and tools. To make a living I worked for book publishing houses and newspaper editorial offices, making illustrations for literary pieces.

“Ever since I was a child, I had known painters and sculptors who were creating abstract pieces of art”

On my first trip abroad to Poland in 1959, I saw, for the first time, original contemporary paintings at exhibitions and museums in Warsaw and it had a powerful effect on me. It was around the same time in Prague that I first saw original paintings by Braque and Picasso. In 1961 I saw many icons in the mountain monasteries of Bulgaria.

What was it like producing challenging, abstract work under the Hungarian socialist regime?

Ever since I was a child, I had known painters and sculptors who were creating abstract pieces of art, and I was also familiar with their works. Therefore I naturally regarded this movement as a potential for new artistic behaviour. However, I soon had to realise that in Hungary these kinds of works were not allowed to be publicly exhibited, nor were they on display in state museums. Nevertheless, it was possible for young artists to see such works in artists’ studios or in apartments of art collectors.

My first journey across the Iron Curtain took me to Italy in the autumn of 1962. Following a brief stay in Venice I spent one year living in Rome as a beneficiary of an Italian state scholarship. I had the opportunity to see the works of my contemporaries in studios, art galleries and museums of modern art. The powerful initiatives of young European and American artists, as well as the abundant use of materials and colours and the sense of form so characteristic of Italians, all had a powerful effect on me. Not to mention the landscapes, townscapes and the old Roman and baroque architecture, which were all a constant inspiration for me.

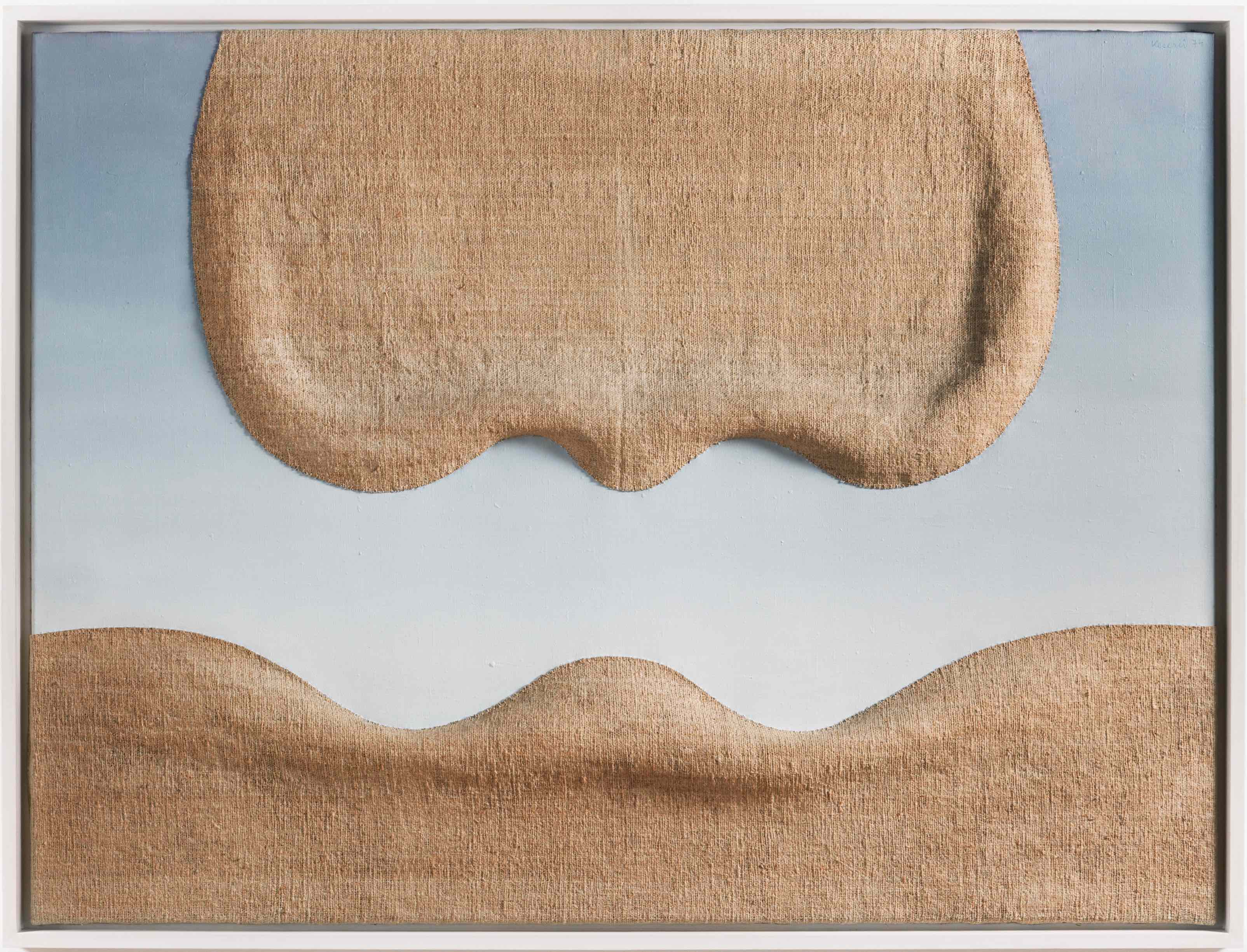

My first solo exhibition opened in Rome at the Galleria Bars in June 1963, where I presented the works I had made in Italy: mostly sketches, drawings of journeys and buildings. Over the six months following the exhibition a striking process unfolded within my work: I found myself. It was time to return home. I drew and painted pebble shapes, masses, curves and baroque fragments.

Can you tell me about the inspiration and influence of the headstones at the cemetery in Balatonudvari?

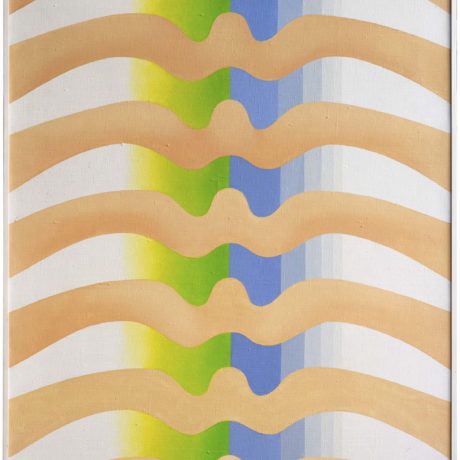

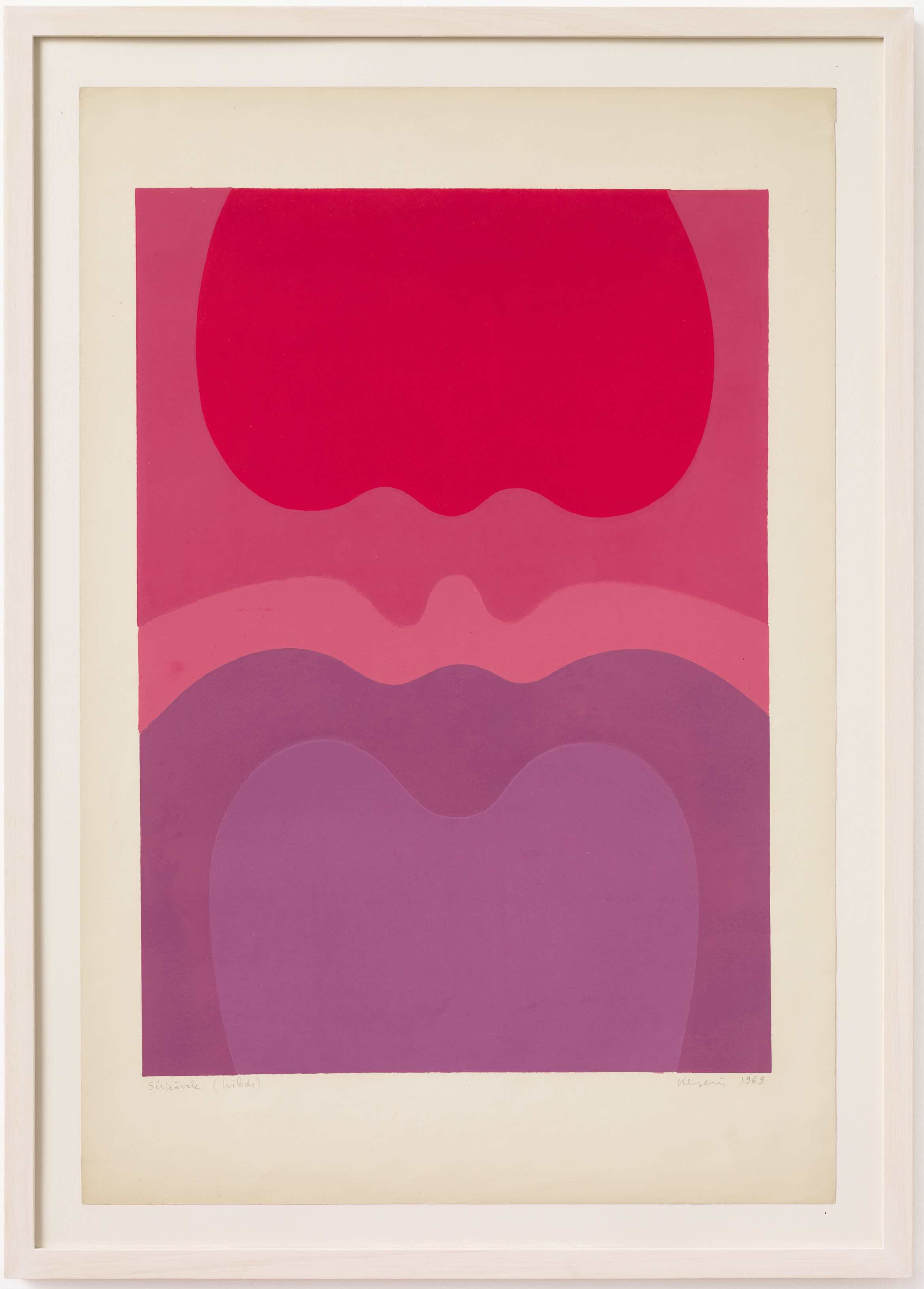

I had seen the heart-shaped tombstones in the cemetery on many occasions but I was first touched by them in some indescribable and powerful way in 1967. The next day I started to make a series of paintings and this shape has been making a regular appearance in my pictures ever since. It related to the undulating forms of my earlier paintings and drawings that were inspired by Italian baroque architecture.

Your use of colour is fascinating. Tell me about your quest to capture the “afterimage”.

I have been much occupied with the pure colours of light refraction and with the greatest colour intensities that can be mixed from paint. It was during this research that I discovered afterimages, which are the most powerful of all my colour experiences. They are the transposed, coloured images of a dark-bright or light-shadow phenomenon we have previously stared at, which appear behind our closed eyelids.

One of the reasons why it has been so fascinating for me is the fact that we all have afterimage experiences, it is common human knowledge. If we look into the sun or any other strong source of light and then close our eyes, we see one or several glowing patches, which are always different depending on the external image and they keep changing even after you close your eyes.

The colours that appear are spectral colours surrounded by a black space. This is a different colour scale to that which we are aware of in nature. It can be compared to gothic stained glass windows viewed in backlight or the bright, radiant colours of the television screen. The afterimages cannot be accurately recreated by using pigments. They are moving, teeming, illusive and luminous processes that are constantly happening. They exist, but I’m not sure that they can be captured or objectified.

All images courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery and Kisterem, © Ilona Keserü