Pop culture increasingly infiltrates formal museums and galleries—in recent years, it feels like there’s been a frothy boom in exhibitions devoted to video games, nightlife or music scenes. On one hand, this is a joyously bold statement, that fun forms and rituals aren’t merely throwaway; they’re locked into our history. On the other, it’s savvy future-proofing by serious institutions, which need to seize the hearts and minds of broader audiences, and younger generations. The British Museum’s much-anticipated manga exhibition goes “pop” on a massive scale—it’s the largest exhibition of the comic phenomenon outside its native Japan—and it’s exhilaratingly exhaustive in its scope.

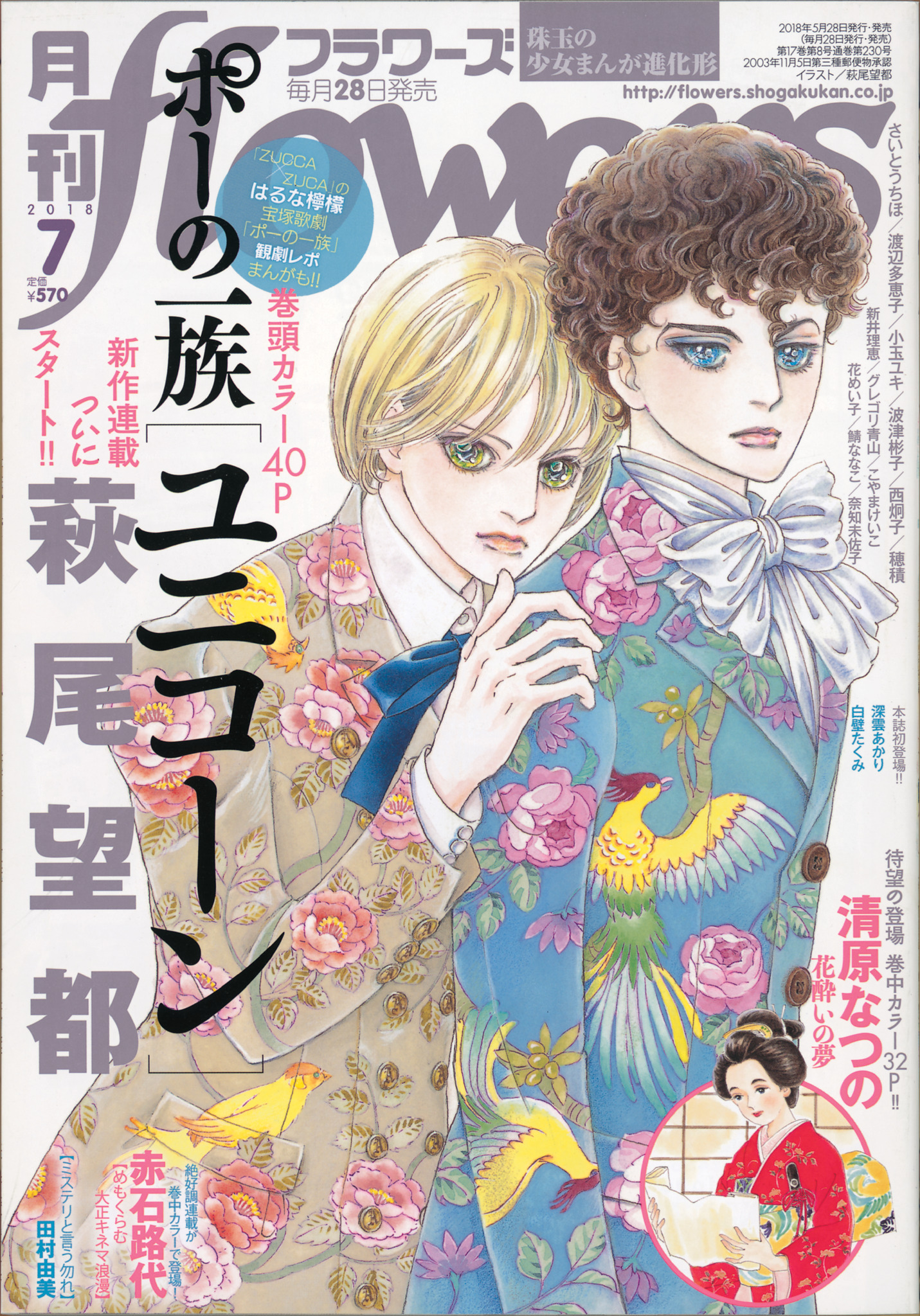

As one of the show’s curators, Dr Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, points out, the Chinese characters that make up the term manga translates as “pictures run riot”. Manga’s contemporary influence, from global multi-media art to mainstream entertainment, definitely feels unconstrained; its dynamic style resonates from high fashion to the high street (where you might buy “manga”-branded hair gel to cultivate that spiky-locked look, spot Pokemon trainers, or browse translated manga serials at your local library). Its legacy is also well considered at the British Museum, which has apparently been collecting manga over the last century; for this exhibition, the roots of manga are traced back to late-nineteenth-century Japan, but its reach feels unusually timeless.

“Manga’s contemporary influence, from global multi-media art to mainstream entertainment, definitely feels unconstrained”

Manga awakens the wide-eyed fangirl/boy in masses of us, regardless of gender or generation—perhaps it’s due to its boundless fantasy and variety of themes (sci-fi; sport; horror; music; gender fluidity; historical epic, such as Noda Satoru’s modern hit Golden Kamuy, which provides the exhibition’s main poster artwork; “boys’ love”—the range is endless), the beauty of its form, or what Rousmaniere describes as “the power of the line”: in manga comics, we engage with the ink itself.

That sense of excitement is key to this exhibition; it’s immediate yet also richly layered and sleekly streamlined. There’s a breathtaking quality to the large-scale original genga (manga illustration) works, with Japanese artists’ blood types (believed to signify their creative tendencies) included on the accompanying bios. Part of the exhibition’s challenge was that manga is a form you’d ordinarily hold in your hands, not display on a wall—but it commands the cavernous space here. There’s also a genuine thrill when you encounter a favourite character—in my case, the hyper-cute android Astro Boy (one of the most famous mid-twentieth-century creations of Osamu Tezuka, aka “the godfather of manga”, who was both influenced by, and a major influence on, Disney).

Rousmaniere’s own passion for manga was sparked during her time spent studying archaeology and teaching in Japan; in 2015, she curated the British Museum’s relatively bijou (but widely acclaimed) Manga Now, and her academic background (in ceramics and three-dimensional objects) also brings a refreshing perspective to an exhibition that attempts to consider manga “in the round”: historically, societally, materially.

“I view comics very much like the ceramics industry,” she says. “It’s about mass production of artistic material that serves almost a higher purpose of industrial design. It’s a very democratic medium.”

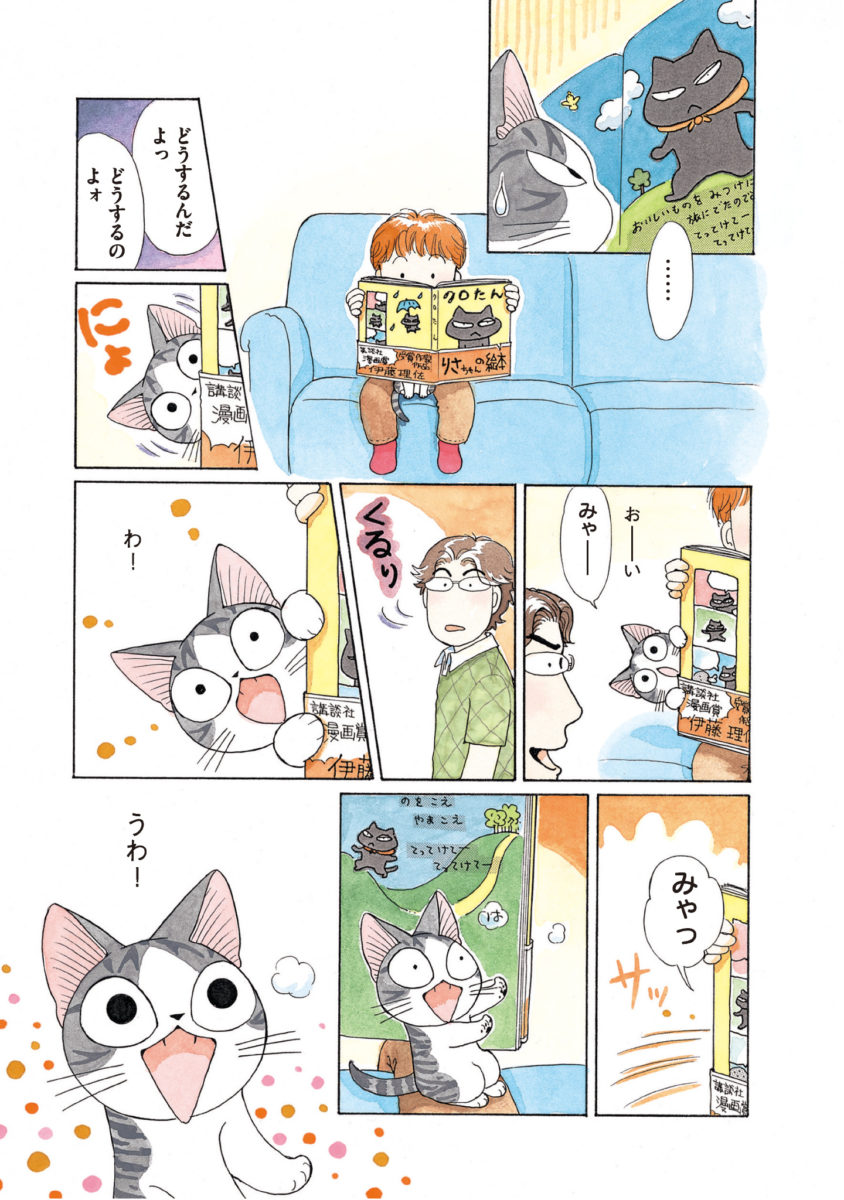

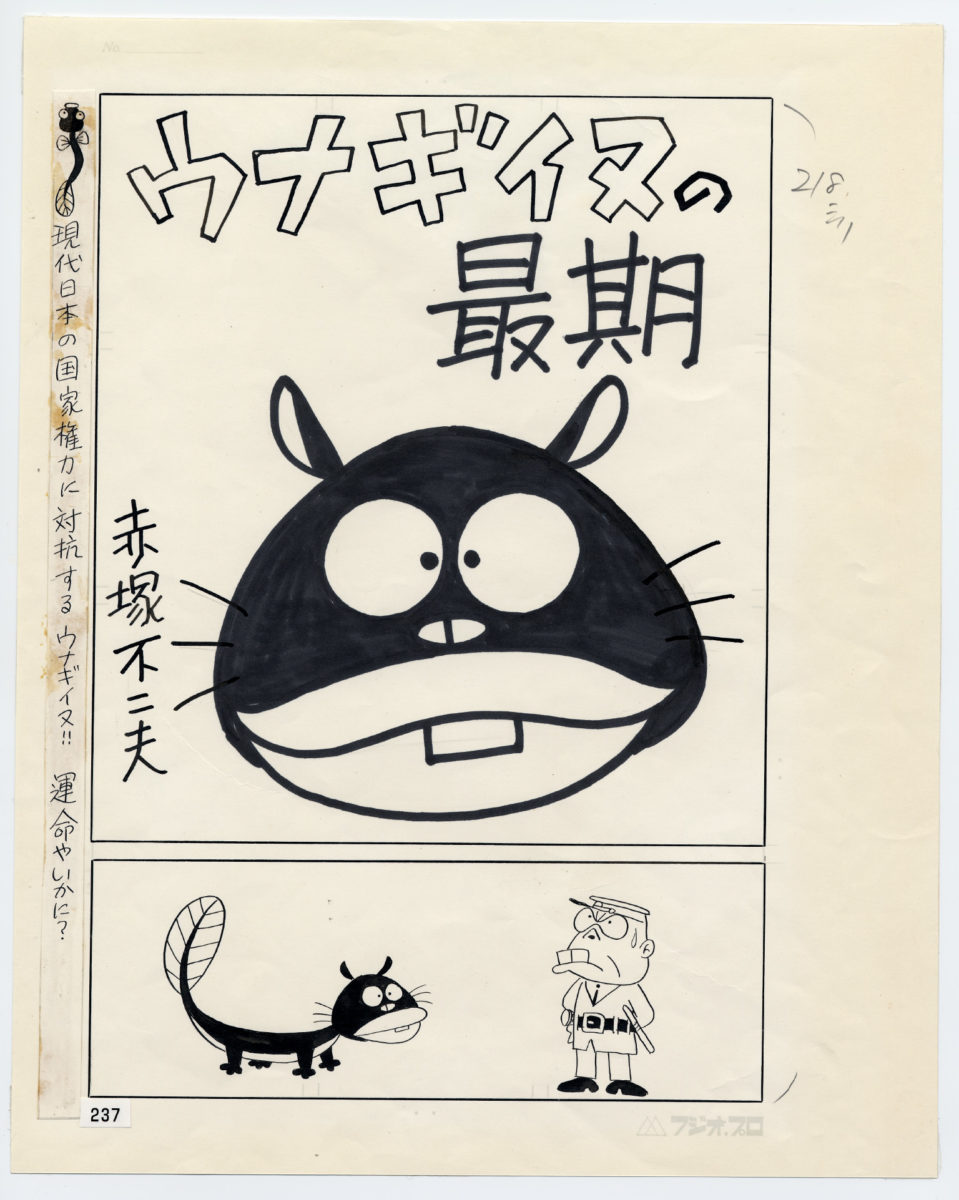

- Left: Komani Kanata (b.1958), Chi’s Sweet Home, 2004-2015 © Konami Kanata / Kodansha Ltd; Right: Akatsuka Fujio, The End of Unagi-inu (Eel-dog), 1973 © Fujio Akatsuka

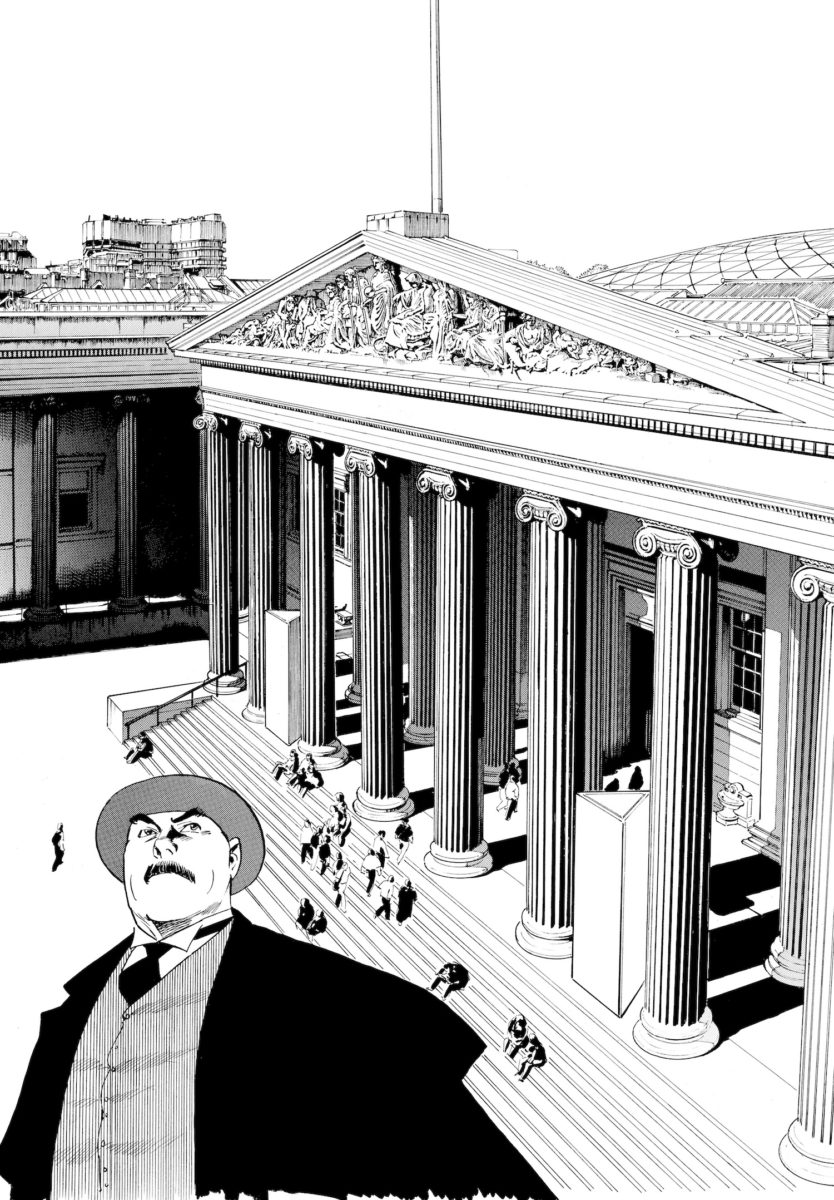

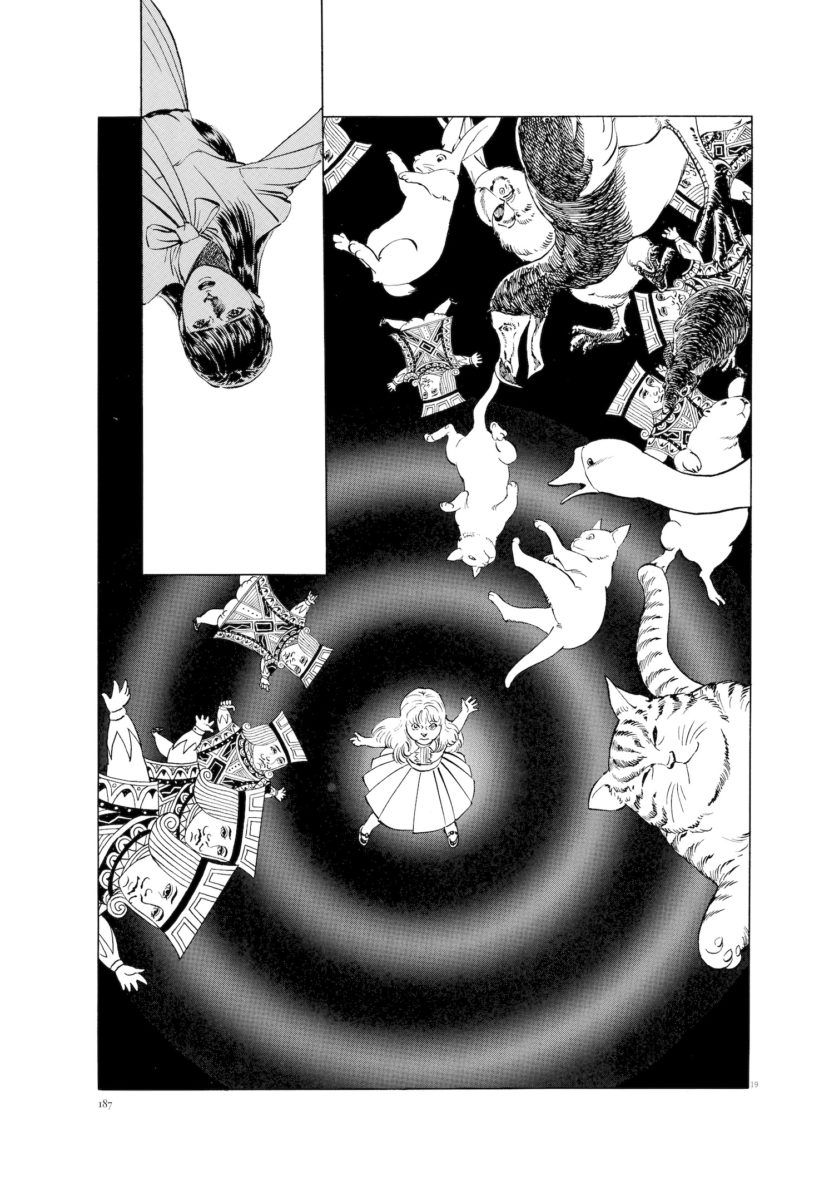

Manga’s international connections are reflected throughout; we’re guided through the exhibition zones by an Alice in Wonderland-style white rabbit, Mimi-chan (with an additional nod to Japanese takes on Lewis Carroll’s nineteenth-century novel, including one by Katsuhiro Otomo, creator of the seminal smash Akira); its publications include the late-nineteenth century satire of Japan Punch, published by Japan-based English artist Charles Wirgman; we see international translations of manga, including Arabic for Syrian children displaced by war: comic art becomes escapism and empowerment.

“Manga began as a disposable, ‘pulp’ medium. It was discarded in bins at train stations”

My love of manga was an extension of a childhood fascination with comics and cartoons (European, American, Asian), and an early desire to become a comic artist. The anime feature film of Akira—Katsuhiro Otomo’s electrifying post-apocalyptic vision set in “Neo-Tokyo”, 2019—was released when I was at school, and it led me back to the comic store, manga… and eventually, writing a twenty-something fangirl letter to British publication Manga Max, which was intercepted by its editor, Jonathan Clements: a translator of Japanese, Mandarin and Cantonese and expert commentator, who has published more incisive, entertaining insights about manga than any other writer in the UK. Clements’s Manga Snapshot column in NEO magazine has been going strong for fourteen years; his Schoolgirl Milky Crisis essays explore the behind-the-scenes drama of the manga/anime industry, and his latest book, Attack of the Red Panda, will be out this year.

“Manga began as a disposable, ‘pulp’ medium. It was discarded in bins at train stations,” says Clements. “So much of it was ephemeral, only valued in hindsight. Even today, there are huge swathes of the manga business that only exist as electrons in e-books. So part of the problem with manga is how to mount it as an exhibit. The International Manga Museum in Kyoto, for example, is a wonderful, Tardis-like library experience for Japanese visitors, but I’ve seen many a sad foreigner mooching around there, who sees nothing but shelf after shelf of books they can’t read.”

“A lot of fandom organizers got out in the mid-noughties when the Pokemon generation got old enough to drink!”

The digital age has definitely extended manga’s reach, changing the way that it is designed and distributed. Rousmaniere notes that its visual power works well with Instagram and mobile format—and I think that Snapchat-style filters transform us all into manga-fied caricatures. The increasing range of global expos and “cosplay” options is also an indication that manga has come of age, without losing its love of fantasy.

“A lot of fandom organizers got out in the mid-noughties when the Pokemon generation got old enough to drink!” says Clements. “These days, we’re actually looking at gender parity in UK anime and manga fandom, which is not something that even the Japanese can really boast of. It significantly changes the kind of titles that are popular, and the kind of demographics you see at conventions.”

- Left: Hoshino Yukinobu (b. 1954), Professor Munakata’s British Museum Adventure, 2011; Right: Hoshino Yukinobu, Alice, 1985 © Hoshino Yukinobu/Shogakuka inc

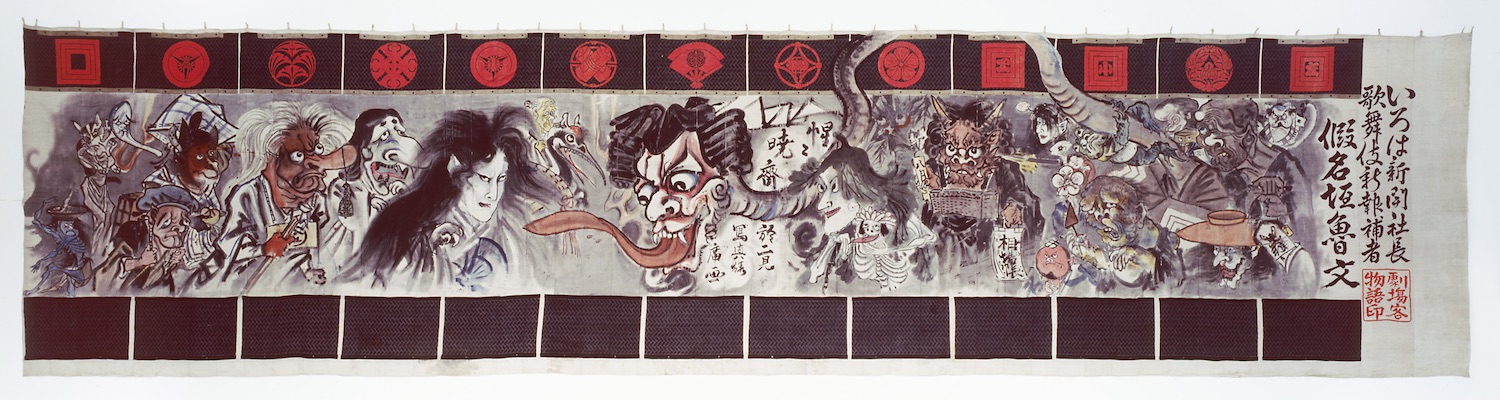

The emotional impact of manga also shouldn’t be underestimated. The British Museum exhibition is packed with moments of heart-swelling joy (the clips of much-loved Studio Ghibli anime, say), devastating narratives (including prolific artist Fumiyo Kono’s Hiroshima-set Town of Evening Calm, Country of Cherry Blossoms, 2004), and eerie wonder—particularly in the expansive kabuki theatre curtain, hand-painted by Kawanabe Kyōsai in 1880. Amid the curtain’s florid-shape-shifting figures, we can make out the nineteenth-century artist’s own footprints, and we feel as though we are mingling with ghosts. Manga is also three-dimensional here—in the explosive sculptural work of Akatsuka Reiko (daughter of legendary “gag manga” artist Fujio), and Hosono Hitomi’s playful yet poignant ceramic series Food Heaven Seven Sisters Rd (2018).

It would be impossible to fully contain these “pictures run riot”, with their dizzying array of genres (Clements mentions that Japanese publishers continue to experiment with manga for senior generations; his upcoming Manga Snapshots columns will include “a manga gossip mag for the Tokyo curtain-twitcher, manga for the game-card collector, and manga for gays about town”). But it feels absolutely right to consider and celebrate their art in this way—vast and infinite.