Sometimes they speak of the many faces of the country: its geography, history and people, but sometimes they only suggest an atmosphere, unconnected to the place they were made. Angola might be distant to me for now, but Luanda—Angola’s notoriously expensive capital—will come to London in October, in the form of Kiluanji Kia Henda’s multimedia Frieze Artist Award commission.

“How can we talk about “African Contemporary Art”, or even “Angolan Contemporary Art”, when it has not been defined or developed on the continent?” Says Dominik Tanner, director of ELA, (Espaço Luanda Arte), in the heart of the old part of the Angolan capital, in an area where many of Angola’s most prominent artists used to have their ateliers—Antonio Ole, Paulo Jazz, Kapela Paulo.

“We were and remain particularly keen in nurturing Angolan artists not only from Luanda but also the Provinces, and also holding pan-African collaborations so that non-Angolan artists can come and work with their colleagues in Luanda, and Angolan artists can go the other way.”

“First we must address that there are few galleries, and maybe too many artists not really doing ‘art’ but, instead, maybe doing Arts & Crafts.” Tanner asserts.

“Angola has a lot to offer; on every street corner, there are people telling stories about their life and the country…”

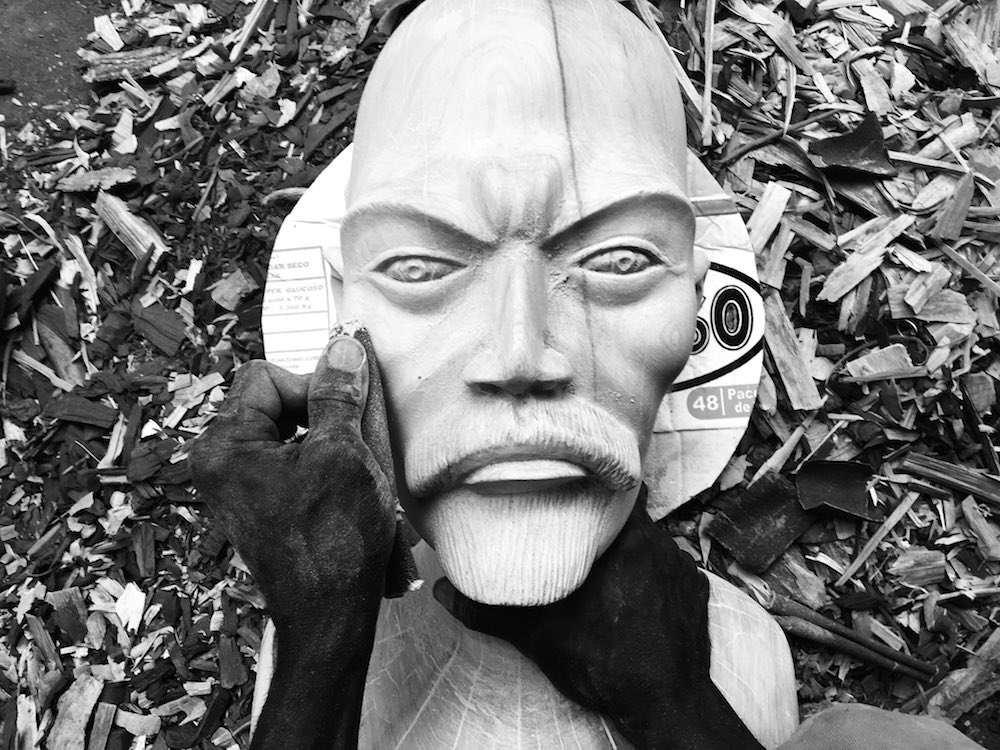

In Kia Henda’s Frieze project, titled Under the Silent Eye of Lenin there are certainly elements of both Angolan art and craft: the artist, who worked on the installation between Lisbon, Luanda and New York, has collaborated with local artisans to create wooden sculptural pieces, including a replica bust of Lenin—that stood in Angola’s main square during the nation’s Marxist-Leninist era.

“Angola has a lot to offer; on every street corner, there are people telling stories about their life and the country. I love the educational stories told by the elders that daily remember our independence and the fight they had to go through to be where we are today. Angolans have become my greatest source of information and education about our history.” Says KEYEZUA, who lives and works in Luanda, and is at the forefront of a burgeoning feminist art movement in Angola.

“On the streets, we have female vendors that we call zungueiras and they walk miles through the city to sell food and other products, but unfortunately it’s considered illegal. Although they are taking a risk, these women are consistent, their resistance is such a fundamental act of what is being an Angolan woman today.These interactions have changed my way of viewing my own challenges, it feels as if each Angolan woman is fighting a battle in their own way but we are all fighting for the freedom of the female body and its rights.”

“We don’t have enough female artists in Angola, some still need to give birth to the artist in them. I feel that I contribute to it by working to become a great female artist.” She adds.

In 2015, KEYEZUA, Kia Henda and other Angolan artists such as Edson Chagas established an artist-run project in an abandoned hotel, “FUCKIN’ GLOBO”. Each artist takes a room and self-funds it as a space for exhibitions, projects, talks and other activities. “Since my arrival in 2015, I have followed different groups of young people demanding change, politically, economically and socially by using art as a communication weapon. Internationally, Angola is well known for its oil and diamonds. Through art, as an artist we can explore these topics in Angola but when exhibited internationally we become ambassadors, we invite viewers of our art to explore Angolan stories not as “African artists” creating “typical African art,” but as Angolan artists creating to explore and exhibit Angola ́s development and its interaction with the rest of the world.”

Portuguese artist RitaGT relocated to Luanda in 2009, where in 2013 she set up e-studio Luanda, an artist collective, project space and studio complex, with the patronage of ACCA by CL (Angola’s Collection of Contemporary Art). E-studio has played a fundamental role in Luanda’s visual arts scene, through exhibition and an educational programme, but also by making links with the international community, arranging exchanges with Tiwani Contemporary in London, but also forging links closer to home. “I feel that is essential to build up a more closely-knit network on the continent, in between the countries.” Being in Angola has also shaped Rita’s own practice. “The city inspires me a lot, as there is so much creativity going on all day. Luanda makes me feel useful, and I always wanted to conduct my art practice with social preoccupations, which are all combined here.”

Délio Jasse, from Luanda and currently living in Milan, says that his city is constantly changing—so much so that it’s hard to keep track. Though he left when he was 18, he returns frequently, to work on new projects there. In his work, Jasse plucks found pictures from found family photo albums, introducing them to various photographic analogue printing techniques, such as platinum and cyanotype, as well as a few printing methods he’s developed himself, dissembling the complexities of post-colonialism through photography, as collective memory—and his own personal experiences, as an Angolan living in Portugal and Italy. Jasse has solo exhibitions coming up at Spazio 1929, Switzerland, in October, and at the Bamako Biennale in Mali, in November.

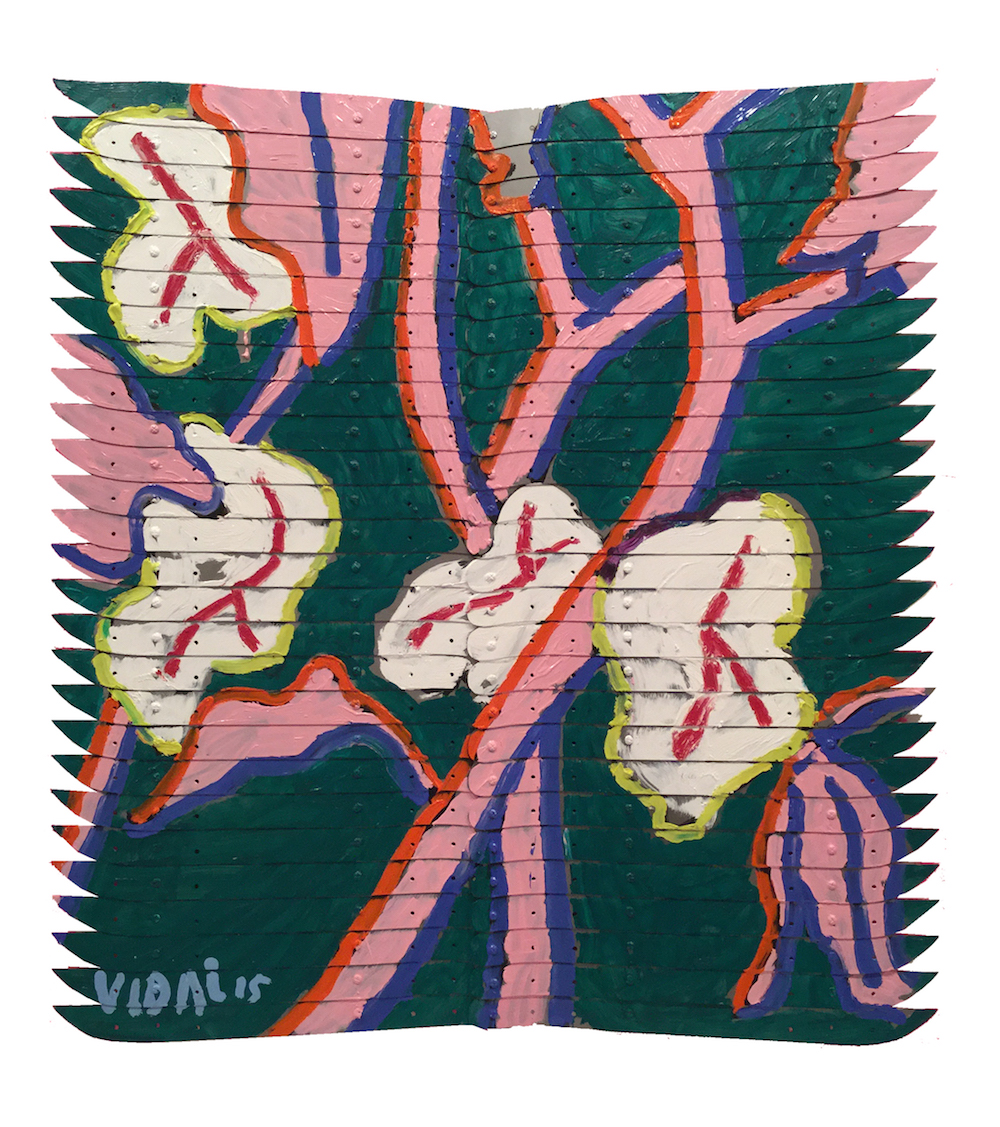

Born in Lisbon to Angolan and Cape Verdean parents, Francisco Vidal—who now lives between Luanda and Lisbon—is another artist whose inside-outside perspective on Angola’s colonial past has lead to an interest in how it is retold. The flowers often featured in his paintings reference an uprising of agricultural workers at a cotton plantation owned by Portuguese and Belgian colonisers in 1961—considered the first fight in the bitter Angolan War of Independence, that culminated in 1974, but did not bring an end to conflict in the country.

Meanwhile, Adalberto Ferreira, or as he’s more widely known, “Toy Boy”, a self-trained artist involved for many years with Luanda’s historic Elinga Theatre, represents the spirit of the capital city’s present: dynamic, shifting, adaptable. Figures and motifs in Ferreira’s paintings explore the socio-cultural reality of Angola’s cities and rural areas, their customs, people and architecture, as they are today.

“In the spirit of Wangari Maathai, I would think that African Contemporary Art ought to be part and take part of a much larger process by which African nationals and non-nationals, but residents on the continent actively discuss what they “owe themselves”, rather than what the outside world owes Africa,” Tanner adds. “For this reason, it is not only important for African galleries to represent African artists, but also for Africans to take a more active part in defining and developing exactly what African Contemporary Art is.” Angola’s artists are proving they’re more than capable of doing that.