1976. A year of drought and disintegration—strikes, swarming ladybirds and a war (of sorts) between the UK and Iceland over cod. Inflation hit twenty-four per cent, and in June the pound plunged to a record low against the dollar. Britain’s financial crisis prompted first the resignation of prime minister Harold Wilson, then the decision by his successor James Callaghan to borrow £2.3 billion from the International Monetary Fund. At the Labour Party conference that autumn, Callaghan caused shock by declaring that the “cosy world is gone”.

As political fixers predicted imminent national collapse, kaftan-wearing balladeer Demis Roussos rode high in the album charts. The year’s best-selling single was the Eurovision winner, Brotherhood of Man’s Save Your Kisses for Me, and the most watched TV broadcast was an episode of police drama The Sweeney, which reached 20.68 million viewers.

Meanwhile London’s Tate was being vilified for its decision to spend £2,297 acquiring Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII, a rectangular display of 120 fire bricks. “What a Load of Rubbish,” pronounced the front page of the Daily Mirror. Just over a mile away at the ICA, an exhibition with the title Prostitution seemed, to conservative observers, an even grosser example of moral breakdown. One MP denounced its creators, art collective COUM, as the “wreckers of civilization”.

“Listen to the Sex Pistols now and you can’t fail to hear what made them, more than forty years ago, seem fresh and unsettling”

It was amid these economic anxieties and art world wranglings, and in defiance of a music scene enamoured of Demis Roussos’s pleading falsetto, that punk burst into life. From the doldrums came a howl of dissent. It would develop into a movement, or at least a memorably angry stance, but before that it was a mixture of protest song and punch-up, led by young people who had a look—bored, moody, skinny, spiky—and a sound to match.

In February, the Sex Pistols played at the Marquee Club on Wardour Street in Soho, London. Storming the stage, they seemed like gatecrashers, enlivening a tired party before ripping it apart. Their keynote was antagonism, born of a disgust at what they perceived as a safe, insipid and unequal status quo. Their tone was raucous and declamatory, and though it was influenced by glam rock’s nihilism as well as the no-frills assertiveness of English pub rock and the predatory aggression of American acts such as the Stooges, it had an air of threatening bluntness that was very much its own.

Skint, Vulnerable and Alienated

At the time the band comprised guitarist Steve Jones, bassist Glen Matlock, drummer Paul Cook and singer John Lydon, whom Jones gave the unwelcome nickname Johnny Rotten on account of his green teeth. Jones and Cook came from Shepherd’s Bush, then notorious as the stomping ground of TV’s Steptoe and Son, while Matlock’s family had gravitated from Kensal Green to what he called the “horrible suburbia” of Greenford, and Lydon, the child of Irish immigrants, had grown up in a grim part of Holloway, where, by his own account, he contracted meningitis from rat-infested water in the backyard.

The four of them were skint and to varying degrees vulnerable, alienated from the affluence of inner London. Melody Maker magazine would in due course quote Jones: “Ordinary life is so dull that I get out of it as much as possible.” Getting out of it meant avoiding or evading the drabness of routine, and it meant milking whatever opportunities came their way. Jones and his bandmates were chafing against received notions of good looks and good taste. They were kicking, too, against the idea of the rock millionaire, most visibly embodied at that time by the Rolling Stones.

The gig at the Marquee wasn’t the Sex Pistols’ first. That had been the previous year, in a fifth-floor common room at St Martin’s College of Art, where Matlock was doing a foundation course. There they’d supported Bazooka Joe (whose bassist was Stuart Goddard, later Adam Ant) and played for twenty minutes before Jeremy Diggle, the president of the student union, terminated the performance by cutting the power to their amps.

In England’s Dreaming, his hefty history of punk, Jon Savage suggests that the initial reaction to the band was “fifty per cent indifference, twenty-five per cent hostility, twenty per cent hilarity and five per cent immediate empathy”. Over the next few months, “to most of their small audiences, their music was just scraping and gnawing sounds”. But for the five per cent, to see and hear them was to become part of their oppositional energy. If one feature of this was a rebellion against suburban greyness, another was a refusal to explain the nature of that rebellion.

Young Sexy Assassins, Programmed for Confrontation

By the time they appeared at the Marquee, the Sex Pistols had performed on eight or nine occasions—in Chelsea and Kensington as well as Watford and Chislehurst—and the King’s Road boutique owner Malcolm McLaren had been nurturing them for six months. McLaren, a one-man ideas factory, had previously managed the New York Dolls, who combined flamboyant androgyny with a preening self-destructiveness. The experience had alerted him to something that was missing from British music. In Manhattan, he’d encountered an arty proto-punk scene: at the East Village club CBGB he’d seen Richard Hell (real name Richard Meyers), a spiky-haired musician whose torn clothes were sometimes held together with safety pins. Hell’s style owed something to the dishevelment of the city’s rent boys, and his air of numbness had more than a little to do with his drug use, but McLaren immediately recognized the potential of an attempt to replicate his blank look and choppy style.

According to one school of thought, John Lydon’s look was modelled on Hell’s. Others, among them Glen Matlock, have argued that Lydon arrived at his image independently. What’s for sure is that the Pistols, seen by McLaren as “young, sexy assassins”, became a vehicle for his dreams of an explosive mixture of music and fashion. Later accounts, often excitable in tone, would represent them as his Dada experiment. According to Jon Savage, they were a means for McLaren to “act out his fantasies of conflict and revenge on a decaying culture”. He had “programmed” them for confrontation.

Kamikaze Exhibitionism

The Marquee was hardly an obvious choice for either Dadaist brouhaha or musical revolution. As Savage notes, this was “the heart of enemy territory”; the venue was associated with the operatic heavy metal of Judas Priest and with acts such as blues guitarist Stan Webb and Mancunian comedy rockers Alberto y Lost Trios Paranoias. The Pistols found themselves supporting Eddie and the Hot Rods, a pub rock act from Essex known for their fast, loud, sweaty style. Serving up a brief but indelible lesson in kamikaze exhibitionism, they smashed up the Hot Rods’ equipment, ensuring they’d never be asked to return. According to Glen Matlock, “It was the first time we’d had proper monitors on stage—which meant it was the first time John [Lydon] heard his own voice. And he didn’t like what he heard. So he trashed the monitors.”

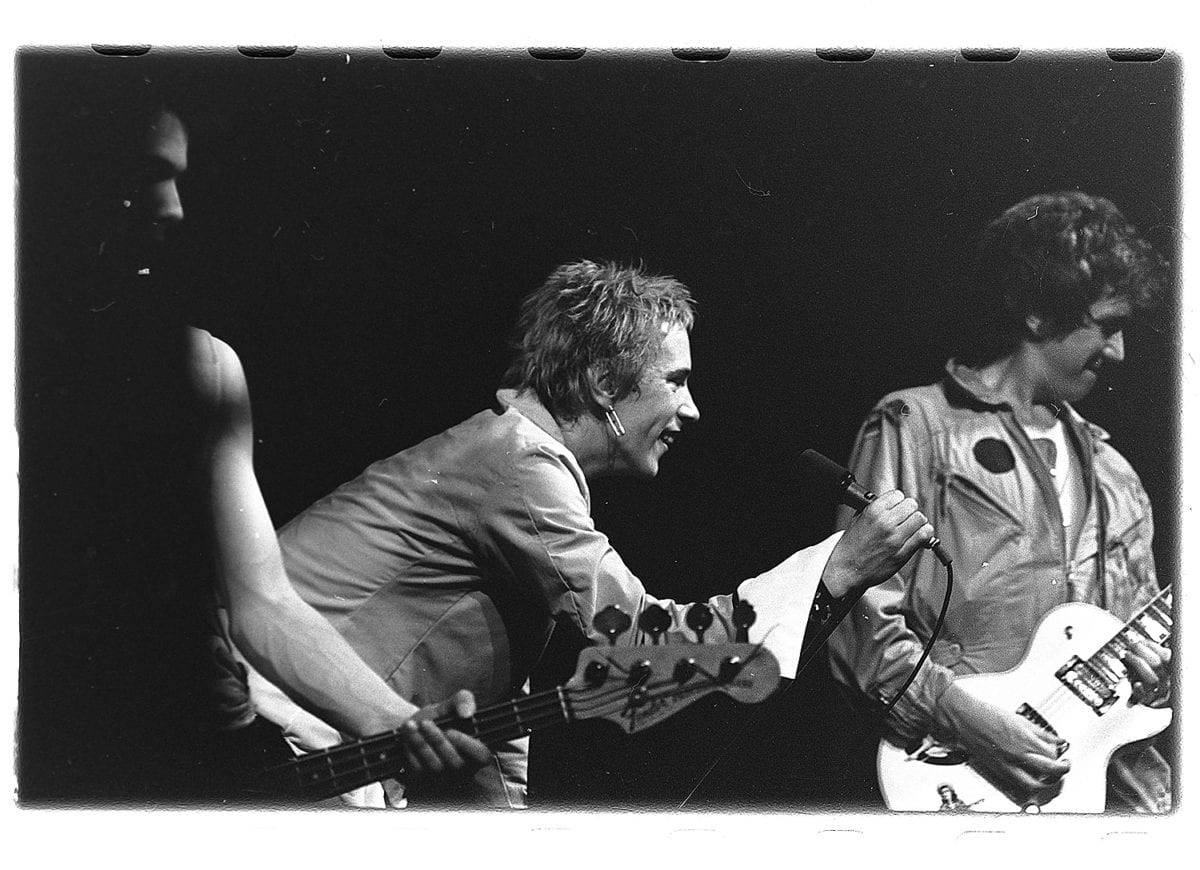

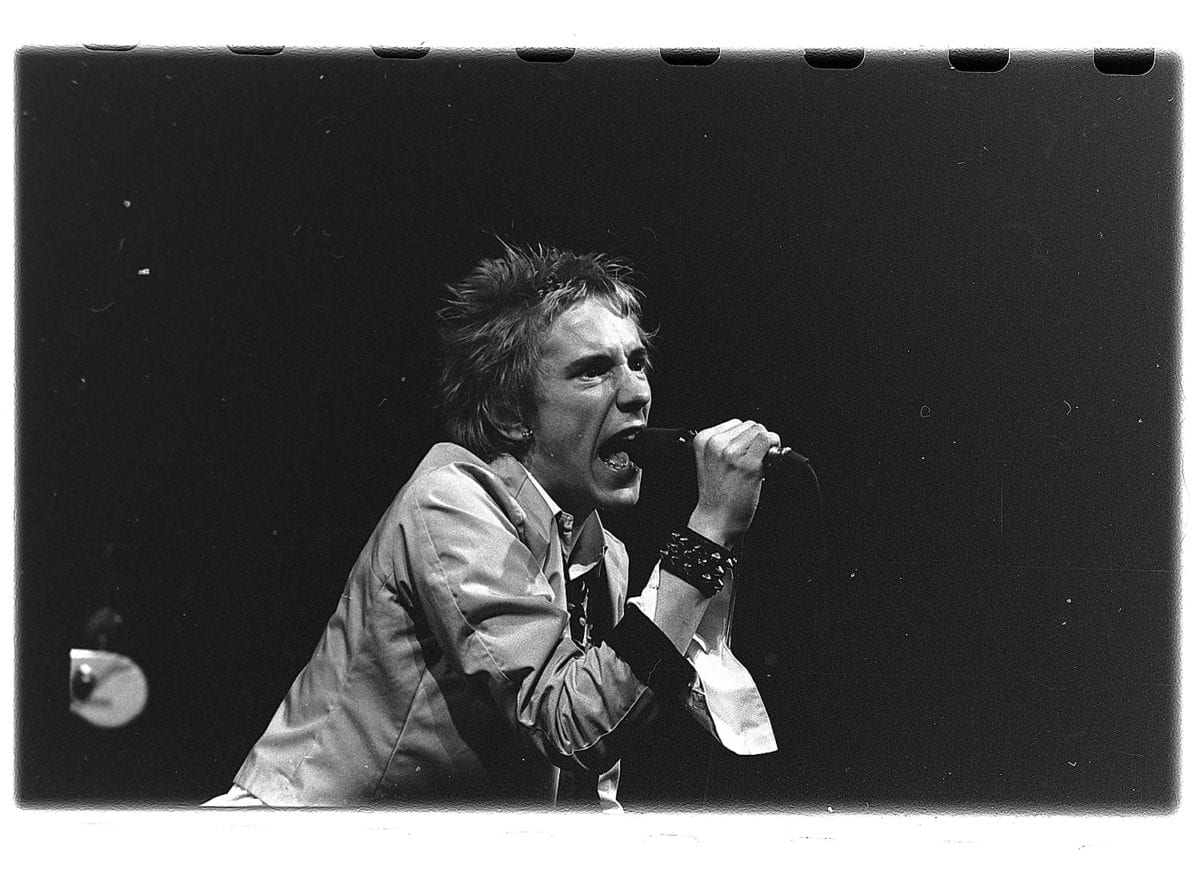

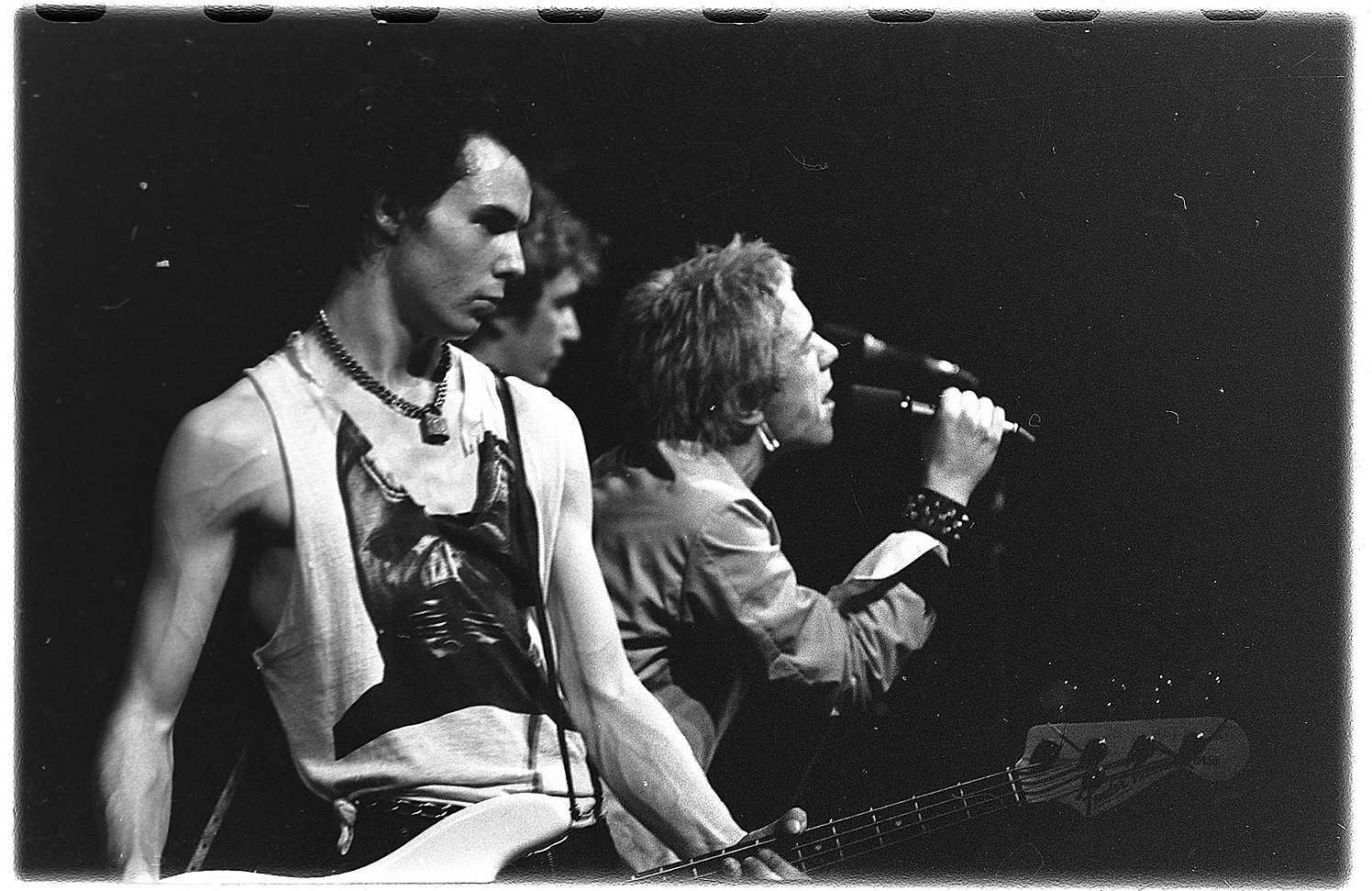

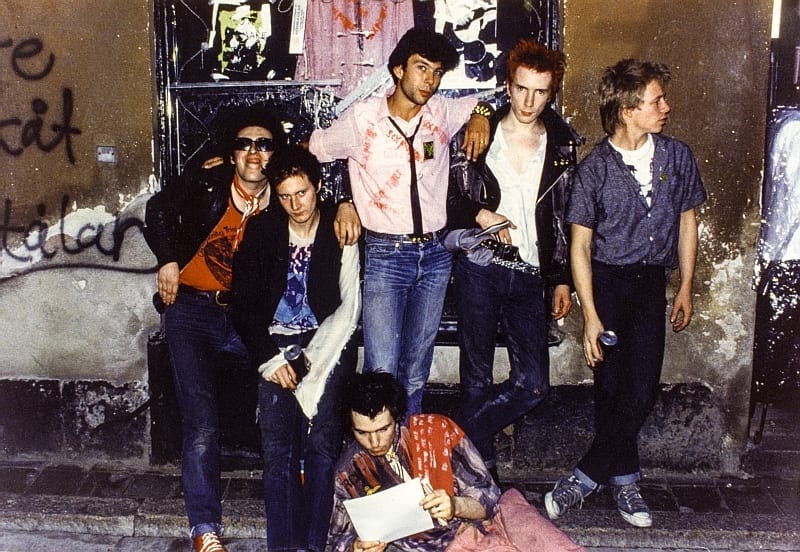

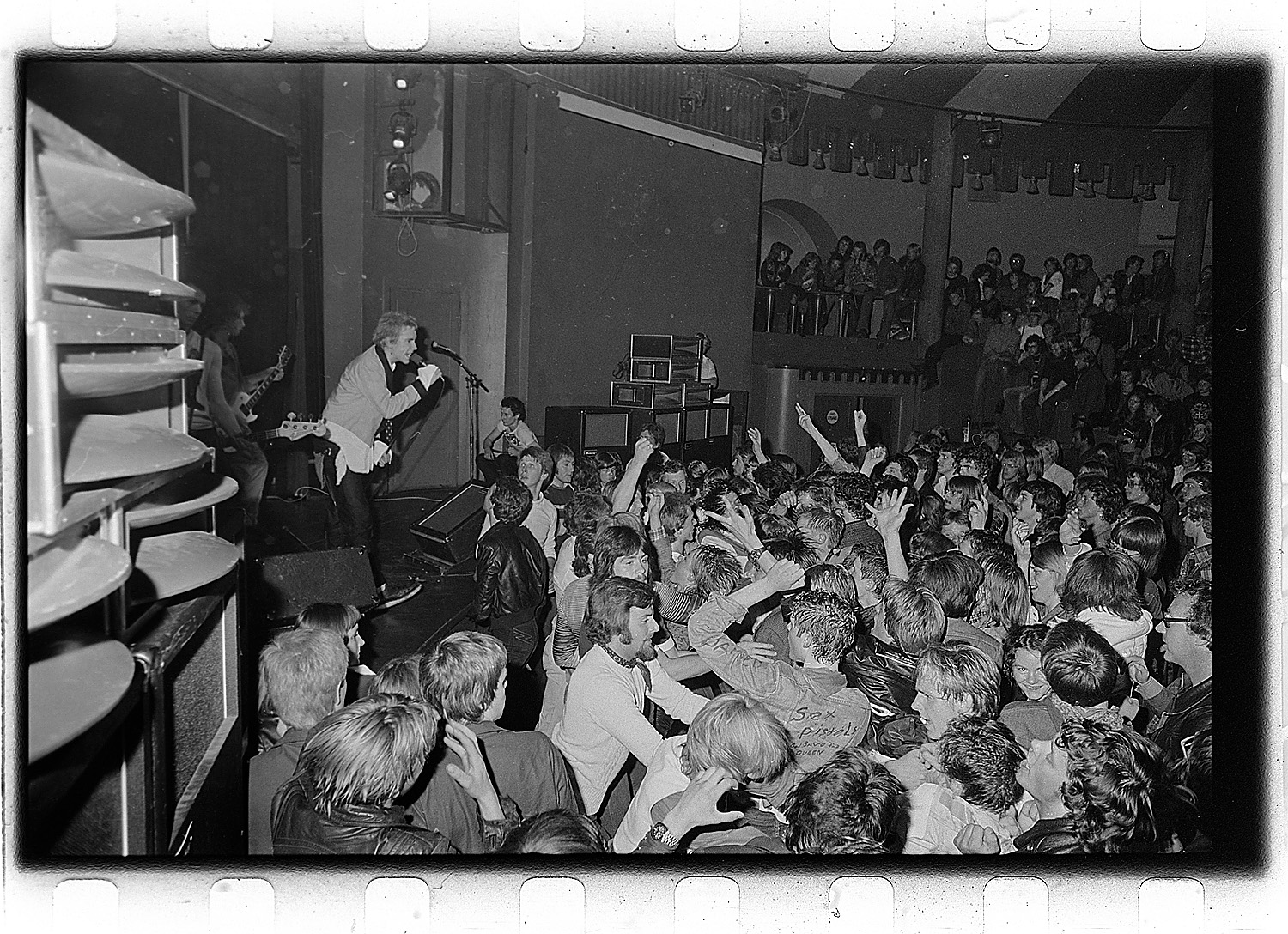

- Above and top: Arne S Nielsen, Sex Pistols play at the student union in Trondheim, 1977. Wikimedia Commons

Neil Spencer of the New Musical Express was present and intrigued. After speaking to the band backstage he wrote an eye-catching review of their performance, headlined: “Don’t look over your shoulder, but the Sex Pistols are coming.” Spencer registered their “small but fanatic following”, and made it clear that in a straight-up fight they’d shred the opposition. When a heckler shouted, “You can’t play,” Matlock countered with a curt “So what?” Apparently impressed by their shambolic cockiness, Spencer concluded his review with a message from Steve Jones: “Actually we’re not into music… We’re into chaos.”

“Queuing on Oxford Street, the fans attracted appalled scrutiny. Were they a circus troupe, a despondent indictment of dole-queue Britain, a cadre of fascists, the flotsam and jetsam of the baby boom?”

Their appearance at the Marquee struck Spencer as a Year Zero moment. Writing three decades on from the event, he recalled their restless attitude and startling look: “Spiky-topped, decked out in sloppy sweaters (Vivienne Westwood’s ‘thalidomide mohairs’), smutty T-shirts, skinny strides and safety-pinned Oxfam finds, they looked like they’d beamed in from a parallel, entropic Britain.”

King Mob on Oxford Street

From the moment of that Marquee appearance in February, the Sex Pistols were in demand. Ron Watts, a former teddy boy who now promoted acts at the 100 Club, booked them to play. The Oxford Street venue had history—as a haven for jazz enthusiasts and later for fans of rhythm and blues. Its bloodshot intimacy suited the Pistols, but the gig, on 30 March, was a mess.

John Lydon’s familiar truculence nearly caused the band to split up that night, but over the next three months they returned five times. By late June their performances had taken on a new tautness and bite. The audience gobbed and pogo-ed, and Lydon showered them with sarcasm, which was precisely what they wanted.

At the 100 Club the Sex Pistols spoke to a young and disaffected audience, many of whom traipsed into London from torpid dormitory towns. Queueing on Oxford Street, the fans attracted appalled scrutiny. Were they a circus troupe, a despondent indictment of dole-queue Britain, a cadre of fascists, the flotsam and jetsam of the baby boom? In their own eyes, the punks were mostly just kids having fun. Some, it’s true, struck an explicit note of political subversion, but for most what mattered was the present; they were the enemies of bombast.

“McLaren duped the media into thinking that a medium-size movement was massive—and lo, the media made it just that”

The band’s appearances at the 100 Club gratified Malcolm McLaren’s sense of history. Since the late sixties he had wanted to make a film about Oxford Street. It was a project that also appealed to his art school friend Jamie Reid, who would later create artwork for the Sex Pistols’ records and play a crucial role in defining the visual language of punk. McLaren had started work on the film with the £50 he received as a result of marrying Jocelyn Hakim, a French-Turkish Jew who needed to stay in the country, and it had stuttered along for eighteen months before being suspended, a victim of the very transience it had set out to document. It didn’t help that the main Oxford Street shops were reluctant to grant him access. Only Selfridge’s had let him in.

What fascinated McLaren about Oxford Street was its hyperactivity, a glitzy pageantry that seemed to strip shoppers of their humanity. At the same time he was intrigued by its gruesome past, above all several centuries of executions at Tyburn (“London’s largest free spectacle”). Another point of reference was the Gordon Riots of 1780, in which a resentful proletariat had risen up, briefly identifying itself as King Mob. That was the kind of story guaranteed to please McLaren, for whom Oxford Street seemed to promise a sickly mixture of commerce and violence, and his first attempt to pinpoint its character came with a manifesto: “Be childish. Be irresponsible. Be disrespectful. Be everything this society hates.”

University of the Streets

McLaren had been putting these principles into practice since his days among the beatniks of Harrow Art School in the mid sixties. Seven years of erratic further education, during which he’d seized upon the ideas of Andy Warhol and the Fluxus network, made him want to turn art’s theories of heresy into disruptive action. One notable escapade occurred in the run-up to Christmas in 1968, when he joined members of an avant-garde group, who’d reclaimed the name King Mob, as they descended on Selfridge’s in a mood of vituperative anti-commercialism. They presented children with toys while distributing flyers that bore a confession from Santa Claus—“It was meant to be great but it’s horrible.” The text was dense and splenetic: “No more midnight neon. No more conspicuous glitter for compulsive sightseers to gawp at the wonders of capitalism… This year Christmas can’t even pretend to be fun… Let’s smash the whole great deception. Occupy the fun palace… Light up Oxford Street. Dance around the fire.”

That reference to the “fun palace” was pointed. In 1961, theatre director Joan Littlewood and architect Cedric Price had given this name to a utopian space they hoped to create, a modern counterpart to London’s eighteenth-century pleasure gardens. Littlewood would manage a couple of times to try out her model of melding performance and public engagement—at Bubble City near St Paul’s in 1968, and at the Stratford Fair of 1975. Yet the period saw Britain’s cities fill up with blank space of a very different kind; its new landmarks were banks and shopping centres. To McLaren’s jaundiced eye, the idea of the fun palace was a symptom of the fizzy optimism of the early sixties, which had been superseded by crisis, bureaucracy, vapid consumerism and a sense of national inadequacy.

“Throughout his strange career, McLaren kept returning to the idea that pranks are profound. He was the Marcel Duchamp of British music, a jester standing next to the abyss”

Eventually McLaren would get to make his film and articulate in his own terms the desire to “light up” this portion of central London. In The Ghosts of Oxford Street (1991) he revisited his fascinated dissatisfaction with a stretch of town which, quoting the nineteenth-century essayist Thomas De Quincey, he likened to a “stony-hearted stepmother”. Serving up a characteristically weird and militant take on the past, he channelled an uncomfortable ambivalence as he associated Oxford Street’s dazzle with misery, boredom and loneliness, while celebrating its darker, more heroic yesterdays. He cast Welsh singer Tom Jones as retail magnate H Gordon Selfridge, John Altman (the villainous Nick Cotton from EastEnders) as an opium-addled De Quincey, and singer-songwriter Kirsty MacColl as Kitty Fisher, the high-class prostitute who is sometimes alleged to have eaten a slice of buttered bread topped with a £100 note.

Scams and Scandals

By 1991, of course, McLaren had made his mark as an Oxford Street impresario. He would speak of the Sex Pistols as his vulgar invention, an attempt to create cash from chaos. He saw them as part of Oxford Street’s long history of scams and scandals, certainly, yet also as a counterblast to the banality of modern living. “We wanted,” he said, “to create a situation where kids would be less interested in buying records than in speaking for themselves.”

Throughout his strange career, McLaren kept returning to the idea that pranks are profound. He was the Marcel Duchamp of British music, a jester standing next to the abyss. At Sex, the King’s Road boutique he ran with Vivienne Westwood, he sold T-shirts inspired by a news story about a rapist terrorizing the city of Cambridge; when he found out that the items had been withdrawn in his absence, he chose to print a new version of the T-shirt, which included a picture of Brian Epstein (who had died in 1967) and some text alluding to Epstein’s alleged enthusiasm for sado-masochism. His purpose? “I think those ideas really invigorated kids,” he told the short-lived New Music News, “and that’s all that was important… to annoy a few people, because they felt so lethargic.”

“That the Pistols sometimes sounded terrible when playing live only deepened their appeal. They made their fans feel that they had licence to sound terrible too”

McLaren’s disciples and admirers have tended to trace his ideas back to an interest in the Situationist International (1957-72). The Situationists’ leading light Guy Debord had argued that modernity and specifically capitalism had lured people away from reality; their lives were instead hopelessly passive, dominated by commodities and bereft of any sense of history. The solution they proposed, much to the liking of McLaren, was a mass awakening from consumerism.

The Great Enabler

Cultural historian Roger Sabin has observed that the link with Situationism was seized on only by a handful of cognoscenti and “never had a deep impact”. In similar vein, journalist Nick Kent is withering about the Sex Pistols’ svengali, regarding him not as a re-interpreter of Situationist rhetoric, but as a mere scene-stealer. For Kent, the essence of the band “didn’t miraculously emanate from Malcolm McLaren’s crackpot art-college concepts”. Instead it derived from Steve Jones, who was annihilating the memory of years of abuse he’d suffered at the hands of his stepfather.

Listen to the Sex Pistols now and you can’t fail to hear what made them, more than forty years ago, seem fresh and unsettling: a self-lacerating glee and festive despair. That they sometimes sounded terrible when playing live only deepened their appeal; they made their fans feel that they had licence to sound terrible too. Their enduring achievement is, of course, their sole studio album Never Mind the Bollocks. Not released till October 1977, it’s a relentless thirty-eight minutes of anthems, be it the feral singalong of God Save the Queen and Anarchy in the UK or the riffy majesty of Pretty Vacant (with its more than passing resemblance to ABBA’s SOS).

But it took McLaren, in Glen Matlock’s phrase “the great enabler”, to turn the Sex Pistols into a project—and one shaped less by his ear than his eye. In September 1976, as a grey autumn clouded memories of the parched summer, he and punk had their perfect Oxford Street moment when the 100 Club hosted a two-day festival. McLaren disliked that term, which he thought tainted by its association with hippies, so it was billed as the 100 Club Punk Special. He duped the media into thinking that a medium-size movement was massive—and lo, the media made it just that.

On the first night, the Sex Pistols performed. They were supported by the Clash, whose frontman Joe Strummer would soon afterwards tell journalist Caroline Coon that his first encounter with the band had been transformative: “Yesterday I thought I was a crud. Then I saw the Sex Pistols and I became a king.” Also on the bill were Siouxsie and the Banshees and Subway Sect; the next night was headlined by the Damned, with support from the Buzzcocks and the Vibrators.

The Filth and the Rury

John Robb’s Punk Rock: An Oral History identifies this as the moment when “punk went overground” and cites Vic Godard of Subway Sect: “Before the 100 Club festival, punk was like a secret society. Afterwards it got hijacked by everybody.” In the space between the before and the after, though, it seemed magical. Among those present were Vivienne Westwood, Chrissie Hynde, Shane MacGowan, Billy Idol and Paul Weller. For Michelle Brigandage, famously photographed in a leopard-print jacket at the head of the queue, seeing the Sex Pistols and especially Lydon “was like a religious experience”.

On 21 September, the second night of the Punk Special, the mood soured. Sid Vicious, who had not yet taken Matlock’s place in the Sex Pistols and had spent the previous night drumming for Siouxsie, tried to throw a glass at the stage as the Damned performed. He missed: the glass hit a pillar and a shard pierced a girl’s eye. He was swiftly bundled out of the venue and into a police car, ending up in Ashford Remand Centre. Punk acts were banned from the 100 Club. Yet Roger Horton, who’d run the venue for over a decade, soon relented. Strife was good for business.

“When Steve Jones had boasted that, ‘Actually we’re not into music… We’re into chaos,’ he’d not begun to realize how photogenic that chaos would prove”

Reports of the glass-throwing incident began a moral panic that would peak that December. Now signed to EMI for £40,000, the Pistols appeared on Thames Television’s teatime Today programme, standing in for their record-company stablemates Queen. During their interview with middle-aged and out-of-his-depth presenter Bill Grundy, Steve Jones said “fuck” three times and Lydon twice said “shit”. Many viewers were shocked, not least by Lydon’s blasé response to being asked what he’d said: “Nothing. A rude word. Next question.” Clive James, touching on the broadcast in the Observer that weekend, remarked, “This was the first time in history that a pop group had ever tried to bite the hand that fed it before it had been fed”.

Suddenly the nation woke up to what the mainstream media chose to characterize as a sordid cult. The Daily Mirror led the charge, reporting the episode beneath the headline “The Filth and the Fury!” The paper even claimed that one viewer had been so incensed he had kicked in the screen of his £380 colour TV. Soon commentators were highlighting punks’ zest for jaggedness and squalor, whether it was an eagerness to “defile” themselves with hair dye and extravagant make-up, a passion for “nasty” fabrics and for transforming bin liners and bog chains into clothing, or their apparent enthusiasm for fetishwear and kinkiness.

A Generation of Catalysts and Culture Warriors

The Sex Pistols invited outraged hyperbole, and one result of the media’s attention to their exploits was the impression that punk was exclusive to London. It wasn’t, and there is a dense and prickly history of punk’s provincial reverberations that’s still to be written. But the Sex Pistols represented the phenomenon at its most spectacular. When Steve Jones had boasted that “Actually we’re not into music… We’re into chaos,” he’d not begun to realize how photogenic that chaos would prove.

It wasn’t long before the Sex Pistols’ disgust turned inwards. Matlock argues that the Bill Grundy episode “drove a wedge right down the middle of the band”. But their brief reign of havoc shook up fashion, youth culture and, most obviously, music. Even if some of the spaces that opened up quickly closed down, sub-scenes developed. Punk sluiced away the last traces of flower power and ushered in an age of independent record labels, musical agitprop and jittery, often art-school-educated bands who said strange and unpalatable things in strange and sometimes palatable ways.

Punk also raised the status of the specialist music press, whose critics functioned as tastemakers and trend-spotters, activists and oracles, not merely mapping the contours of the culture, but shaping them. In Rip It Up and Start Again, his celebration of post-punk, Simon Reynolds notes that the new generation of music journalists “seemed to be made of the same stuff as the music they championed”. They were part of a wave of “catalysts and culture warriors, enablers and ideologues, who started labels, managed bands, published fanzines, promoted gigs and organized festivals”.

This punk spirit lives on. Although there are plenty of mouthy guitar bands who claim to be perpetuating punk’s rebellious energy, it’s perhaps more truly embodied in the small-label, DIY defiance of hard-edged electronic music, or in grime and drill’s urban reportage and rage about class. Punk attitude thrives in experimental theatre, among the art world’s more angular combatants and in radical politics and environmentalism. It’s marked by a disdain for orthodoxy and for bland professionalism, along with a delight in cut-and-paste creativity and the desire to invoke history for subversive ends. At root, though, it’s defined by a simple urge: to punch a hole in the washed-out fabric of normality. In it, and through it.