An upside-down smiley is the first image that I face at the entrance to London’s Science Gallery. The emoticon sets a brightly poppy tone for On Edge: Living in an Age of Anxiety

; it also appears like a signal to that “future” audience (teens to mid-twentysomethings) that most museums and galleries seem increasingly anxious to connect with. Youth experience is certainly key to On Edge; the Science Gallery (set within King’s College London Guy’s campus in central London) pitches itself as a convivial meeting-ground for art, science and health, and much of this latest exhibition is based on research and discussions with young people.

“For generations, we have romanticized the image of the ‘tortured artist’”

Anxiety is a pertinent theme (maybe even a “buzzword”, if we’re deeply cynical about pop psychology); it’s also primal, and universally relatable. That upside-down smiley, the motif for our modern times, holds my attention for a few seconds longer than feels comfortable: deeper and more disturbing than its simple topsy-turvy silliness suggests.

Above: Suzanne Treister, Post-Surveillance Art/NSA Sex Bomb, 2014; Below: Sarah Howe, Consider Falling, 2018

The UK mental health charity Mind defines anxiety as “what we feel when we are worried, tense or afraid—particularly things that are about to happen, or that could happen in the future. Anxiety is a natural human response when we perceive that we are under threat.” It is contradictory by nature: a defence mechanism and a destructive force; a pulse-racing impetus and a crushing impediment. It has always had a fascinating dynamic with art; the brilliant twentieth-century poet TS Eliot famously opined that “anxiety is the handmaiden of creativity”. For generations, we have romanticized the image of the “tortured artist”, and the intense beauty that appears to stem from pain: Edvard Munch’s legendary late-nineteenth century paintings, say, or the raw candour of Van Gogh’s brushstrokes.

We live in an “age of anxiety”—here in the West, in a fractious peacetime, with the knowledge of conflicts and atrocities exploding not too far away—just like our predecessors have, and our descendants almost certainly will. Anxiety is a state of perpetual emotion.

There are seemingly myriad elements to being on edge, and the compact Science Gallery presents an effectively streamlined, accessible range of multimedia expressions. Sarah Howe’s intro installation Consider Falling (2017) evokes a sense of derealization, when we feel detached from our surroundings or even our own bodies. We catch fragments of our reflections within the sharp angles and fragile structures of the piece; we also watch GIFs of other bodies on mirrored screens (nothing is viewed directly): the immediately recognizable signs of anxiety and self-soothing: a pinched lip, clasped arms. Social media is the insidious spectre of this age of anxiety. It tips us all into a heightened state (and for younger generations, it has always existed)—we are constantly switched on, and when we scroll through our news feeds, awake or insomniac, we consume interminable loops of cuteness and trauma.

“Social media is the insidious spectre of this age of anxiety”

Social media obviously also creates a vital platform, on which many individuals are bravely frank about their mental health—although the inevitable trolls among the responses usually indicates that the modern world really isn’t that “woke”. Climate change—a constantly trending topic, and a global trauma that appears to be carried on the youngest shoulders—is a pivotal aspect of On Edge. The exhibition encourages interactivity, via screens, woven material that suggests colourful strands of DNA and, more enticingly, a mini-library/desk where visitors are encouraged to write and read about their fears and aspirations for the world. The informality, and physical tangibility, feels welcoming here; teen activist Greta Thunberg’s book No One Is too Small to Make a Difference rests among the scattered papers. On Edge is political, but its nervous energy is channelled inwards: anxiety spiralling from that feeling of powerlessness, about our personal lives, or the world at large.

The sensory experience of ambience gives rise to some playful approaches here—in Benedict Drew’s sound and light installation, or the trippy riffs of Harold Offeh’s Mindfully Dizzy (2019): an audio mash-up of jazz pioneer Dizzy Gillespie’s music and talking therapies, developed with patients from the Bethlem Royal Hospital’s psychiatric intensive care unit and the charity Hospital Rooms

.

At points, it’s surprising what mundane yet deeply ingrained details might trigger our anxiety; watching Leah Clements’s meditative film To Not Follow Under (2019), which explores the fear of sleep, the scene of a swimmer under shimmering water makes me flinch at my memory of nearly drowning as a kid, and the aquaphobia that has never left me since.

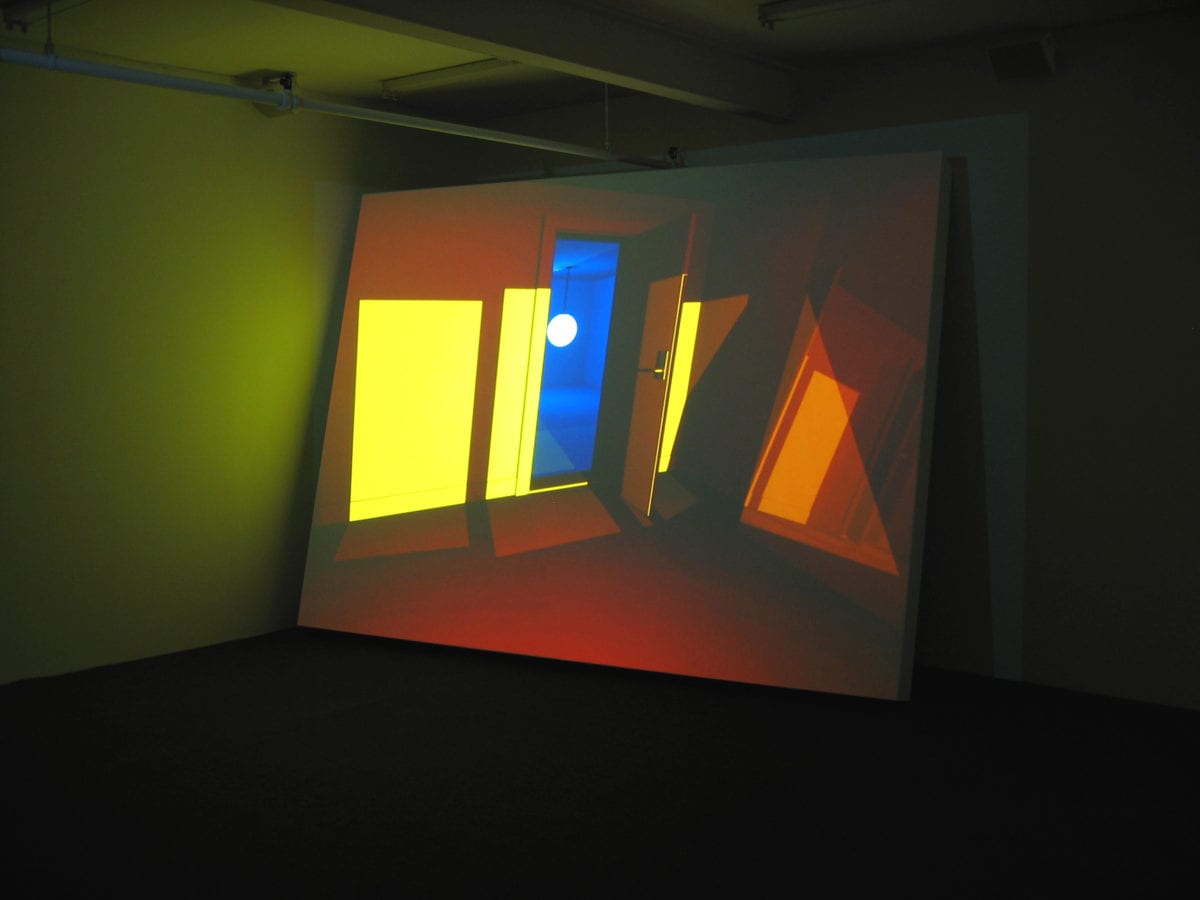

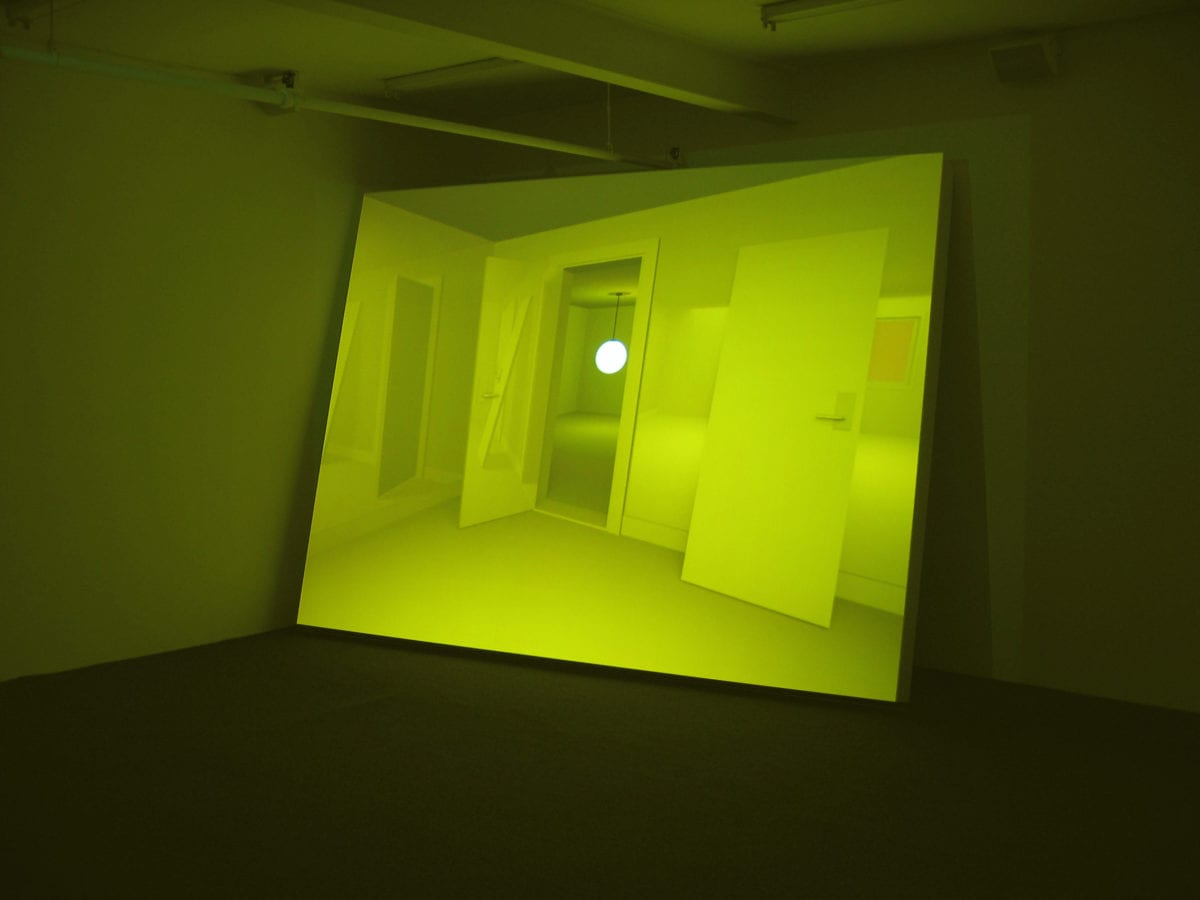

- Ann Lislegaard, Bellona (After Samuel R. Delany) 2005 © the artist

The need for headspace is acknowledged, but so is the significance of solidarity as a coping mechanism for anxiety. The painted slogans of With You, If You Need (Alice May Williams, 2019), are inspired by interviews with female football players. The typography recalls Ed Ruscha as well as contemporary sportwear brands, but the sentiments also feel movingly earnest and inclusive. The exhibition also appeals to its audience via a lively social programme, spanning “Weird Zines” to craft and running events. We might feel a natural urge for solitude; we shouldn’t feel forced to endure it.

“Climate change—a constantly trending topic, and a global trauma that appears to be carried on the youngest shoulders—is a pivotal aspect”

The cold, queasy 3D animation of Ann Lislegaard‘s Bellona (After Samuel R Delany) takes inspiration from Delany’s cult sci-fi novel, Dhalgren, and sends us back to a sense of disconnect. As I’m watching the film, I also glimpse the hubbub of the streets outside, and the pulse of the city feels oddly homely. As we live in an age of anxiety, art offers escape, therapeutic practice, but also reassurance: a shift of perspective that resets our reality, confirmation somehow that we are not the only ones who feel this way.