Eva Hesse and Hannah Wilke made Minimalism erotic. The New York-based artists, who are believed never to have met despite running in similar circles during the 1960s, both developed a distinct form of humanized, sculptural abstraction, evoking a raw sensuality that spoke to the subjective experience of the female body, with varying degrees of subtlety.

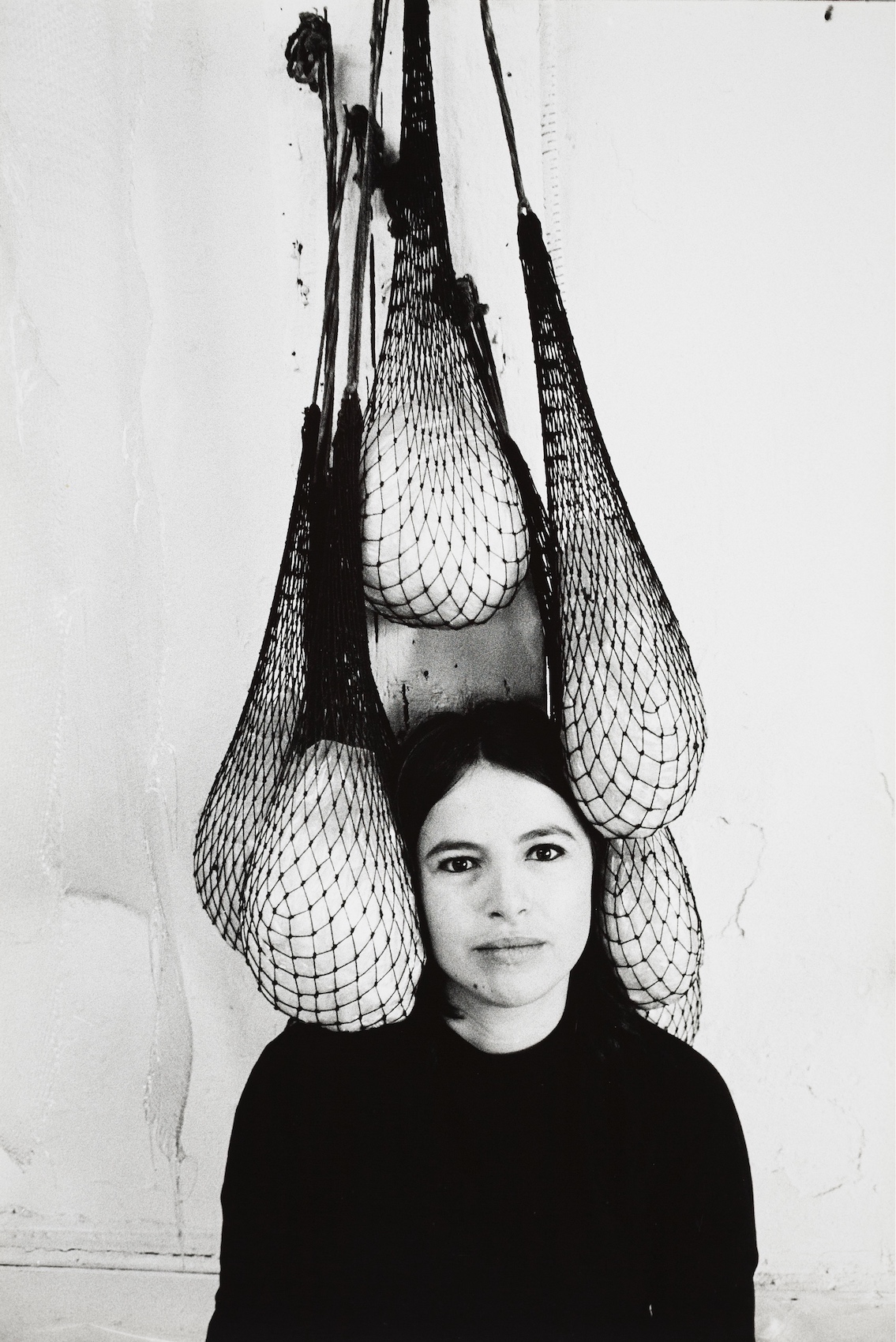

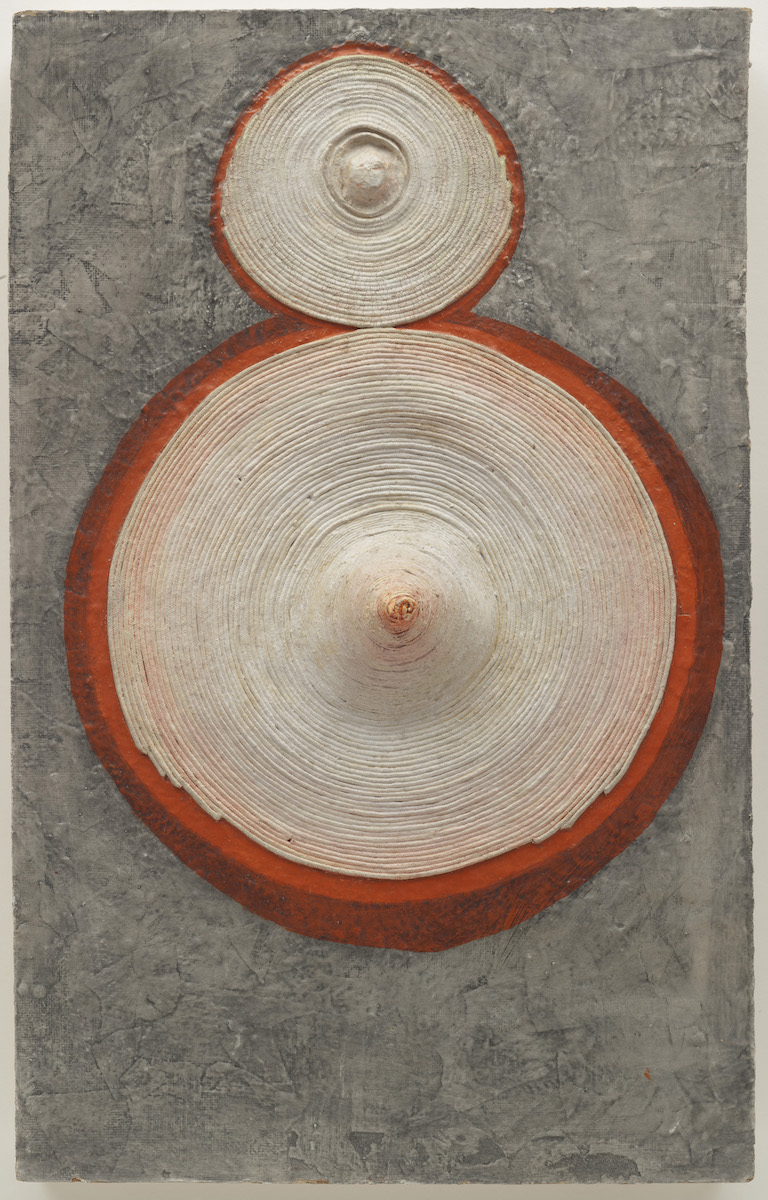

Eleanor Nairne, curator of Eva Hesse/ Hannah Wilke: Erotic Abstraction at Acquavella Galleries, explains that, “Hesse and Wilke shared in the desire to adopt and subvert the strict geometries of Minimalism; softening the language of cool detachment with a sense of physical touch.” For Hesse, this meant breaking free from the seemingly limitless potential of painting—which she had studied at Yale under Josef Albers—and engaging with the more tangible material possibilities of sculpture. She worked with industrial products such as rope, electrical wire and newly-available liquid latex, creating pendulous forms suspended in nets and suggestive mounds on relief-based canvases.

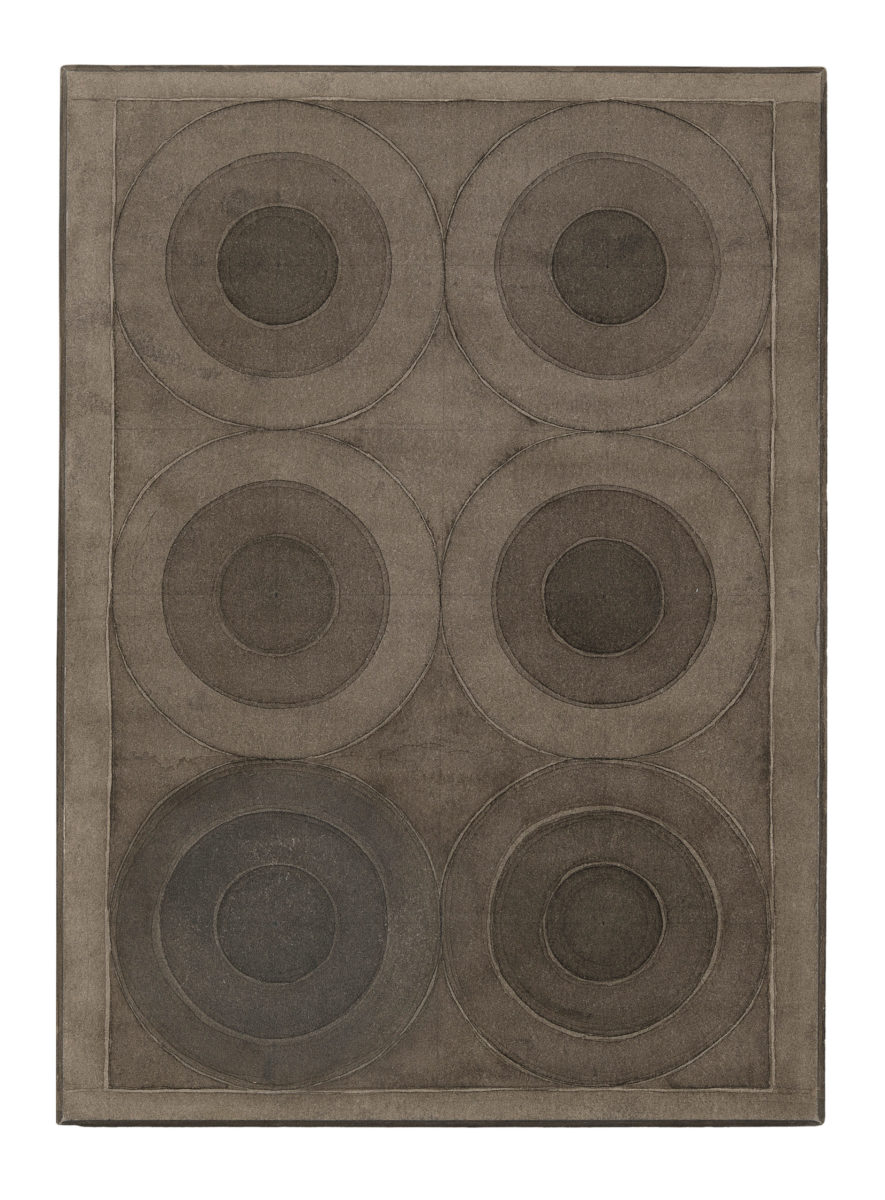

While no one can deny that Hesse’s work was designed to evoke bodily sexuality and even absurdity, the artist was always wary of representational interpretations, as well as the parameters of feminist discourse. When asked about her recurring circle motif by feminist critic Cindy Nemser she evaded any explicit meaning, stating that “I could make up stories for what the circle means to men, but I don’t know if it is that conscious. I don’t think I had a sexual, anthropomorphic, or geometric meaning. It wasn’t a breast and it wasn’t a circle representing life or eternity.”

Hesse was concerned that the notion of a work being identified as “woman” could stunt its impact and was at risk of being othered. At a time when the burgeoning feminist movement was beginning to take hold, she distanced herself somewhat, replying to Nemser’s request for accounts of sexual prejudice with the declaration that “excellence has no sex” and “the best way to beat discrimination is by art”.

It would be wrong to criticize Hesse’s position at a time when the very notion of being an acclaimed female artist was truly exceptional, although her refusal to deny the distinct allusions to testicles, breasts and other suggestive appendages does demonstrate the prevailing attitudes of the period. Sadly, we will never know if she might have later embraced more explicit conversations around gender politics, because she died of a brain tumour in 1970, possibly due to the harmful effects of her chosen materials.

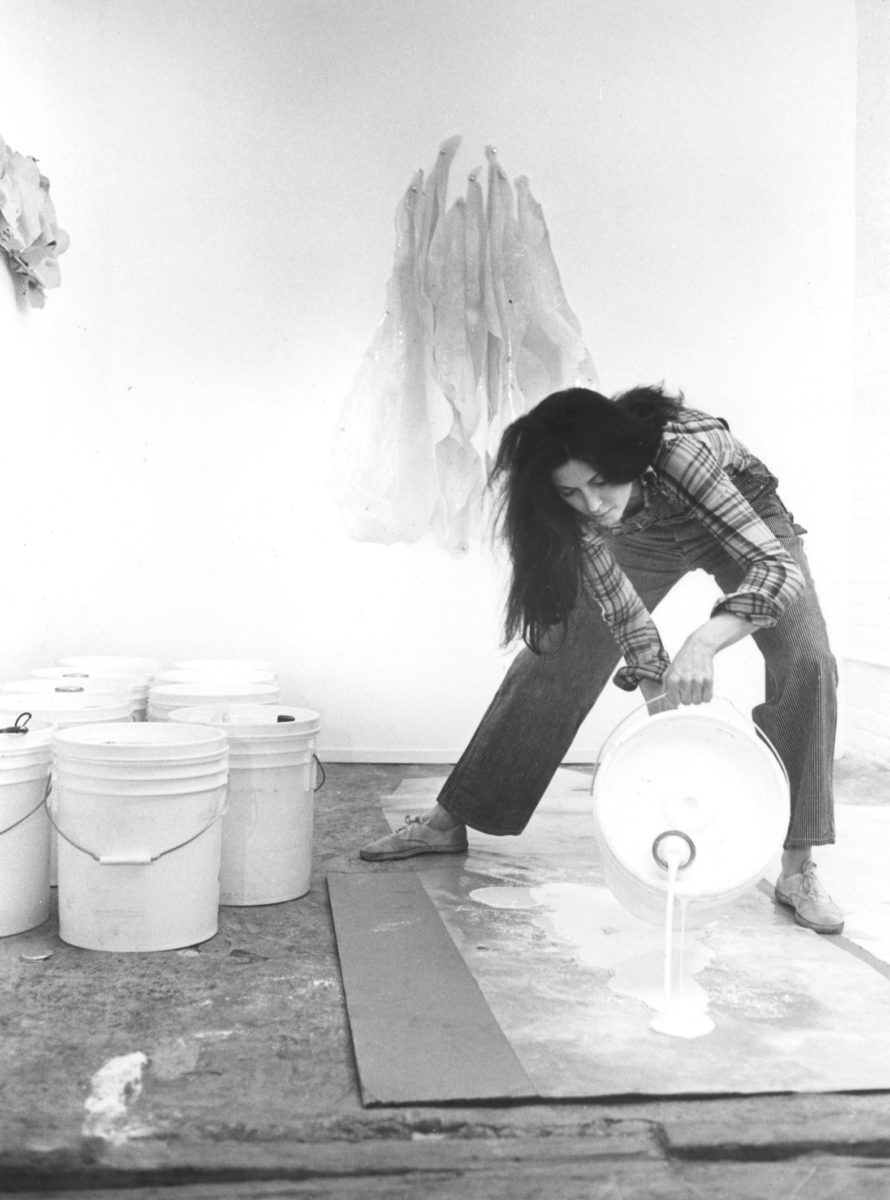

“I have been concerned with the creation of a formal imagery that is specifically female, a new language that fuses mind and body into erotic objects”

- Hannah Wilke pouring latex in her studio, 1974

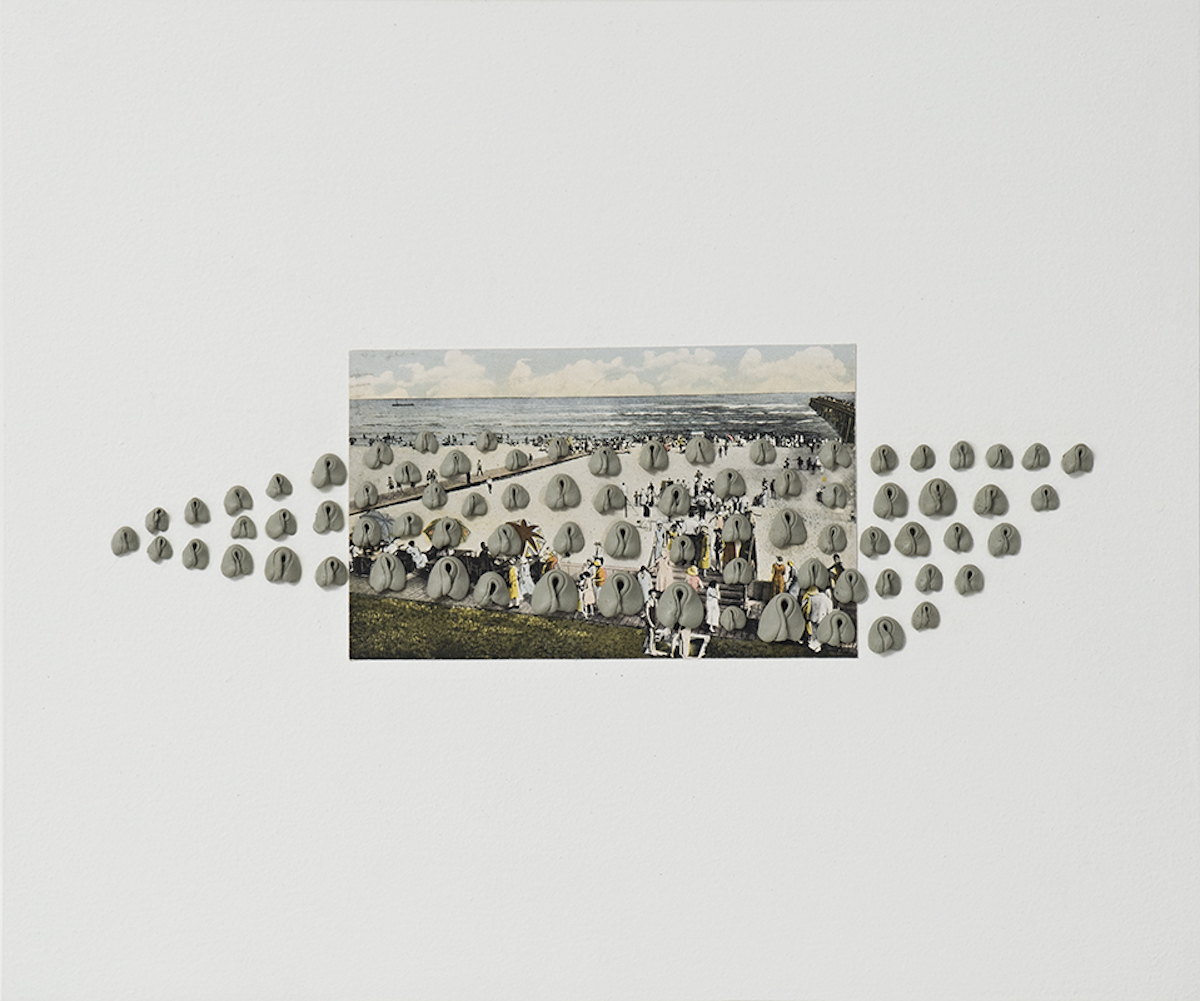

While Hesse’s oeuvre injected a new subtle sensuality into the minimalist aesthetic, Wilke made a conscious choice to boldly embrace her position as a woman: “I have been concerned with the creation of a formal imagery that is specifically female, a new language that fuses mind and body into erotic objects that are nameable and at the same time quite abstract. Its content has always related to my own body and feelings, reflecting pleasure as well as pain, the ambiguity and complexity of emotions.”

Her hand-folded sculptural forms immediately allude to vulva, even adorning her semi-nude body in the S.O.S Starification Object series, where gum chewed by visitors to MoMA were folded into labial shapes and stuck to her skin. As an attractive woman, Wilke sought to challenge preconceptions concerning the male gaze, gender constructs and the notion of sexuality and seduction, by presenting her physical body in direct dialogue with manifestations of female genitalia that are so often vilified as ugly or shameful.

A great fan of latex, Wilke managed to secure the durability of this ground-breaking material by creating her own compound containing Liquitex, and creating multi-layered, fleshy forms that are evocative of both vulva and flayed skin (make of that what you will). These sensual forms most accurately represent the bridge between Wilke and Hesse’s practice, where eroticism is evoked not only in the figurative associations of the work, but the very essence of its material.

Nowadays, it seems impossible not to consider the very formal qualities of sculpture in a way that is susceptible to the multifarious identities of the body, whether that be sexuality, gender, love, sex or violence. Hesse and Wilke were instrumental in developing a new vocabulary that has allowed younger generations of artists to challenge preconceptions around how and why a sculpture is created and what it has come to represent, from Phyllida Barlow‘s enormous assemblages formed from detritus, to Eva Rothschild‘s own latex and gaffer-taped creations.