It’s more than a year since my daughter Athena was born. Looking back, I recall my preparations for parenthood with a flush of embarrassment. Not because I failed to prepare, but because my approach was that of a DIY enthusiast, eager to learn tricks and life hacks or acquire stylish labour-saving contraptions. All the while I felt I was missing some essential piece of information. I half-expected a little door in my head to pop open and reveal a secret store of imperishable wisdom. I now understand that I was looking inside the wrong part of myself.

A month before my wife Tess’s due date, I became fixated with eighteenth-century images of family life. Not the early, starchily formal ones, but the more relaxed, intimately affectionate sort of portraits done by Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds, in which accentuating domestic harmony and children’s playfulness was at least as important as drawing attention to the sitters’ heritage and power.

Why the eighteenth century? Because, I suppose, it’s “my period”—the one I’ve researched and written about most. Those inverted commas are meant to suggest a certain queasiness; I’m a little sick of the assumption that my knowing about Samuel Johnson and Voltaire and the novelist Frances Burney precludes my being aware of, say, Cindy Sherman or Childish Gambino.

Still, there’s no escaping the fact: in advance of Athena’s birth I returned to Gainsborough and Reynolds, Angelica Kauffman and George Romney. Then, as the historical scope of my curiosity broadened, I noticed details that had previously eluded me or examined works that in the past hadn’t held my interest.

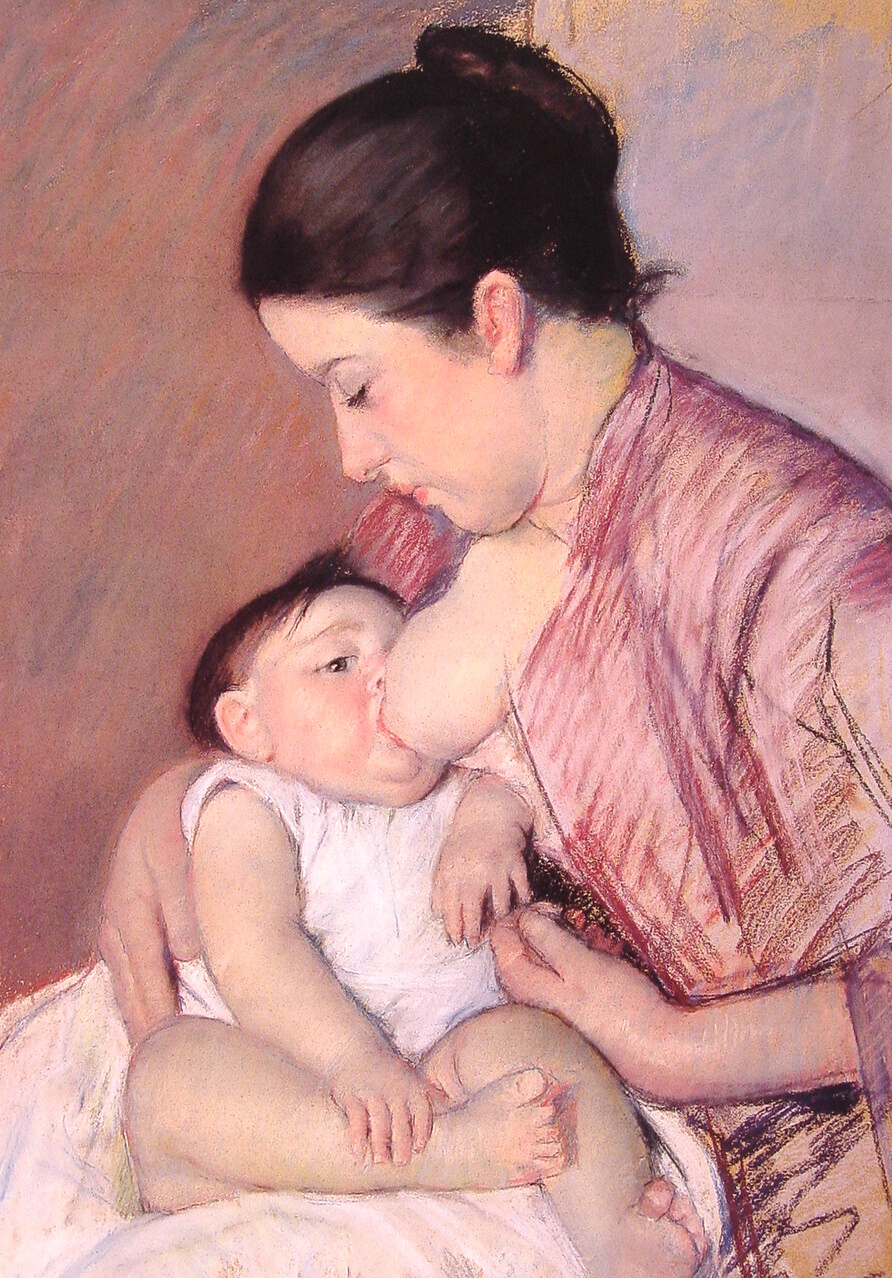

For instance, I’d never looked closely at Mary Cassatt’s images of nursing mothers: their serenity, their attentiveness, their sheer enjoyment of maternity. I knew Thomas Lawrence’s The Calmady Children, without ever having fully appreciated its peachy vitality, and for the first time I was both stirred and scared by the way the younger child, Laura Anne, gives the impression that she might this very instant throw herself in any direction (including ours). I had for years been vaguely familiar with Miriam Schapiro’s “femmages”, acrylics incorporating scraps of ribbon and other fabrics, but suddenly I was fascinated by her piece Father and Daughter, in which the father—a cross between matador, dancer and curtain sample—shepherds a daughter who’s got herself up to look like the world’s most obtrusive spy.

“I’d never looked closely at Mary Cassatt’s images of nursing mothers: their serenity, their attentiveness, their sheer enjoyment of maternity”

Of course, to prepare for parenthood I didn’t just snoop around galleries and ransack Google Images. I read books. I went to classes. I talked to my many friends who’d had children. I looked (once) at a scary website where people apparently go to insult strangers’ approaches to childcare. I watched quite a few YouTube videos, interspersing the relevant ones with guilty pleasures—Roger Federer’s twenty greatest shots or the antics of impossibly fluffy dogs. I attended a breastfeeding workshop. I gratefully accepted gifts from all and sundry; Tess’s hairdresser gave us an extraordinary selection of baby outfits, including seven hats, and the mother of one of her childhood friends knitted ten cardigans that looked like baseball jackets and were all the same size. I bought audiobooks for the occasions when, as I correctly foresaw, I would have my hands full. I laid in extra supplies of cloths and cotton wool pads. I repeatedly tried to picture what lay ahead.

Yet nothing prepared for me how emotional it would be. I’m not talking about the terror and elation around birth itself, or the honeymoon glow of the first two weeks, but about the sudden jags of wonder, pride and fear. The moments in which my consciousness of infancy’s magic and mystery competes with a sense of my vital and abiding responsibilities as a parent.

These moments’ defining quality is this: they make my heart hurt, gloriously. When I hang up Athena’s little socks to dry. When she sees a swan for the first time—or a strawberry, or the Jack Russell in an episode of Frasier. When I hear her tootling away to herself, unaware that I’m listening, and when I finally manage to wrestle her nappy into position and she coos “da-dada” as if to reassure me that despite various minor errors I’ve passed this particular test. When she adjusts the angle of her sun hat, confidently calls a ring-tailed lemur “duck”, hides shreds of kitchen towel in her bib so she can eat them when my back is turned, or rearranges her birthday cards on the mantelpiece as I remove dried-on mango from behind her ear. When Tess gets home from the office and Athena flaps her arms as if trying to take off. When she holds my cheeks, moves in for a kiss and then—surprise!—bites the tip of my nose.

“Nothing prepared me for the moments in which my consciousness of infancy’s magic and mystery competes with a sense of my vital and abiding responsibilities as a parent”

Even the act of writing about these episodes makes the feelings expand inside me. Today, reeling from her attempt to feed me a prune she’s twice dropped on the floor, I decide to show Athena some of the works I’ve written about in this column over the last year. The one that amuses her most is David Černý’s Miminka, a trio of bronze babies with slots where you’d expect their facial features to be. But the one she comes back to—experiencing an attraction that puzzles her a little—is Joseph Wright of Derby’s The Air Pump. There’s a lot going on in the picture. Yet she seems to respond above all to its emotional climate.

It’s one of those paintings that seem to look not only at us, but into us. The central figure is an amateur scientist, laying on a demonstration of a bizarre natural phenomenon, as was so popular in Wright’s day. He enjoins us to become involved—to participate in a moment of entrancement and enlightenment. Naturally, Athena is intent on just this, and, at the risk of over-interpreting her attention, I’d suggest that she sees in Wright’s painting the drama of discovery. Maybe she already grasps that learning about the world is at once exhilarating and distressing, because it unsettles what we think we know.

Yet that’s not all. Because as I look with her at a reproduction of Wright’s painting, I feel drawn into it in a new way—by the silver-haired man and his haunting appearance, yes, and also by her. This, I recognize, is now an ineradicable feature of my life: not simply looking at everything, but looking at it and simultaneously looking at it being looked at.