It was 1981. Manchester reeled from the loss of Joy Division’s Ian Curtis, while Studio 54 prepared to reopen in New York. Thatcher may have been tightening her iron grip but General Franco was dead and a radical clubbing scene was exploding in Valencia that would, for a while, establish the Spanish city as the country’s party hotspot.

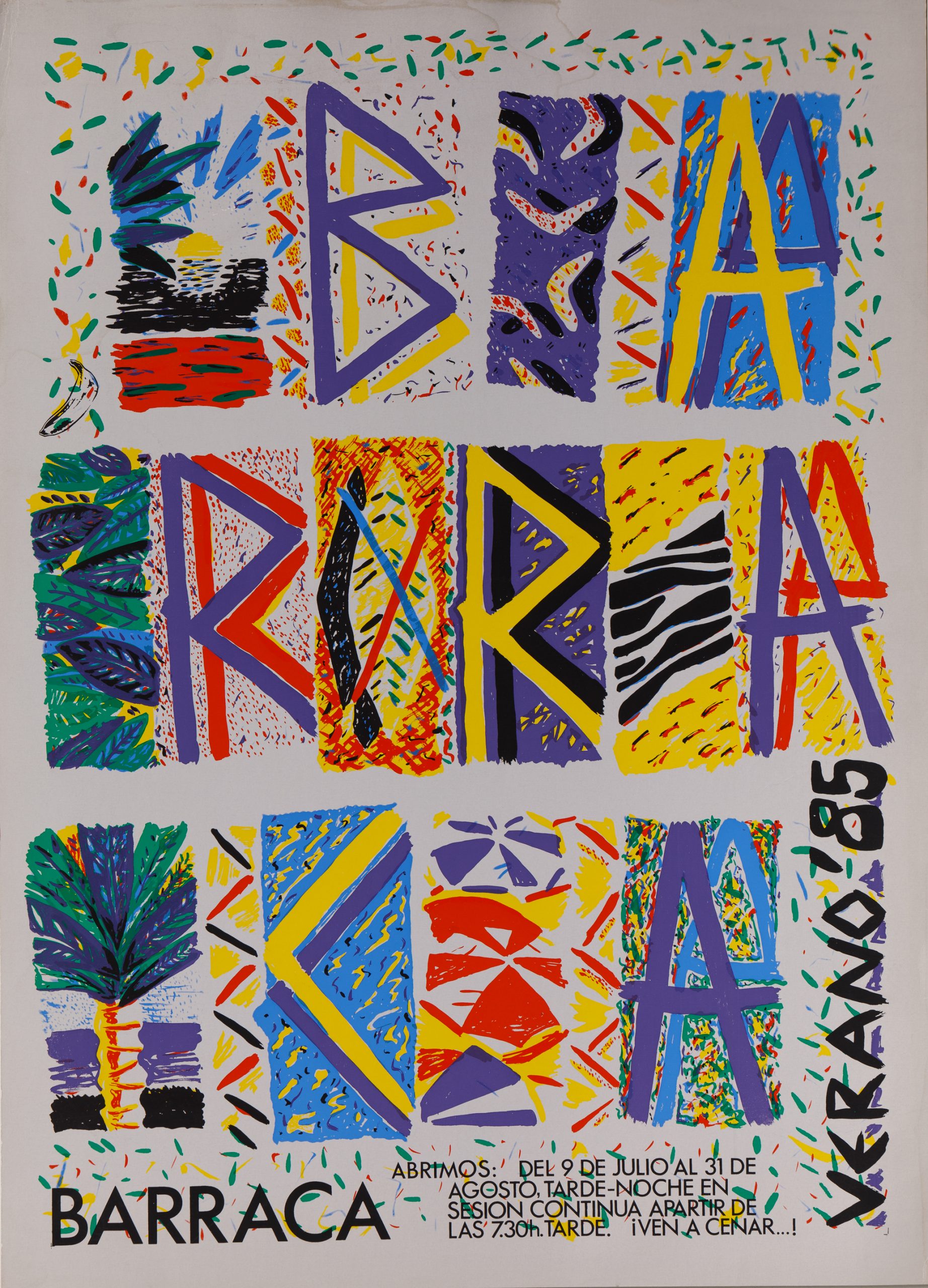

It started with an unofficial party circuit that came to be known as ‘La Ruta’ (The Route). Say the names of nightclubs from the era like Barraca, Chocolate, ACTV and Spook to Valencians today and you’ll stir nostalgic memories of wild weekends on the dancefloor. Together, the various venues made for an explosive combination of sounds, sights and styles that drove partygoers loco.

“This was the first clubbing scene in Spain,” says Antonio J Albertos, one of the curators of Ruta Gráfica: Designs for the Sound of Valencia, a new exhibition at Valencia’s Institute of Modern Art (IVAM) that shines a light on this peculiar moment. “There was so much eclecticism: live music, DJs, theatre performances, fashion shows.”

- Left: Daniel Torres, 1981; centre: Armando Silvestre y Elisa Ayala, 1989; right: Armando Silvestre y Elisa Ayala, 1989

Looking past the partying, the exhibition focuses on the aesthetic culture associated with the nightlife. It features 132 posters used to publicise Valencia’s weekly parties. Mixing collage, illustration, painting, photography, screen-printing and more, the creators of the eye-catching pieces range from the prolific designer Javier Mariscal (part of the Memphis Milano movement) to the all-female design collective Grupo DequeDéque, painting a picture of the cutting-edge artistic creativity that fuelled Valencia’s iconic party scene.

“This was the first clubbing scene in Spain. There was so much eclecticism: live music, DJs, theatre performances, fashion shows”

The iconography associated with this subculture also manifested in stickers, badges, flyers and other pieces of merchandise that circulated across Valencia. In the exhibition are 86 flyers belonging to Moy Santana, from a collection of 2,000 pieces he has amassed since his youth. “I was too young to go to the parties myself, but you would still find these flyers everywhere, in bars and shops,” he explains. “Their aesthetic caught my eye so I started collecting them.”

While the movida madrileña in Spain’s capital made waves with live rock bands, Valencia was all about nightclubs and the curatorial function of the DJ. “In those days, if you wanted to hear certain types of music, you had to go to nightclubs,” explains Alberto Haller, director of Barlin Libros and co-curator of the exhibition. “So the role of the DJ was really important, it formed part of people’s education.”

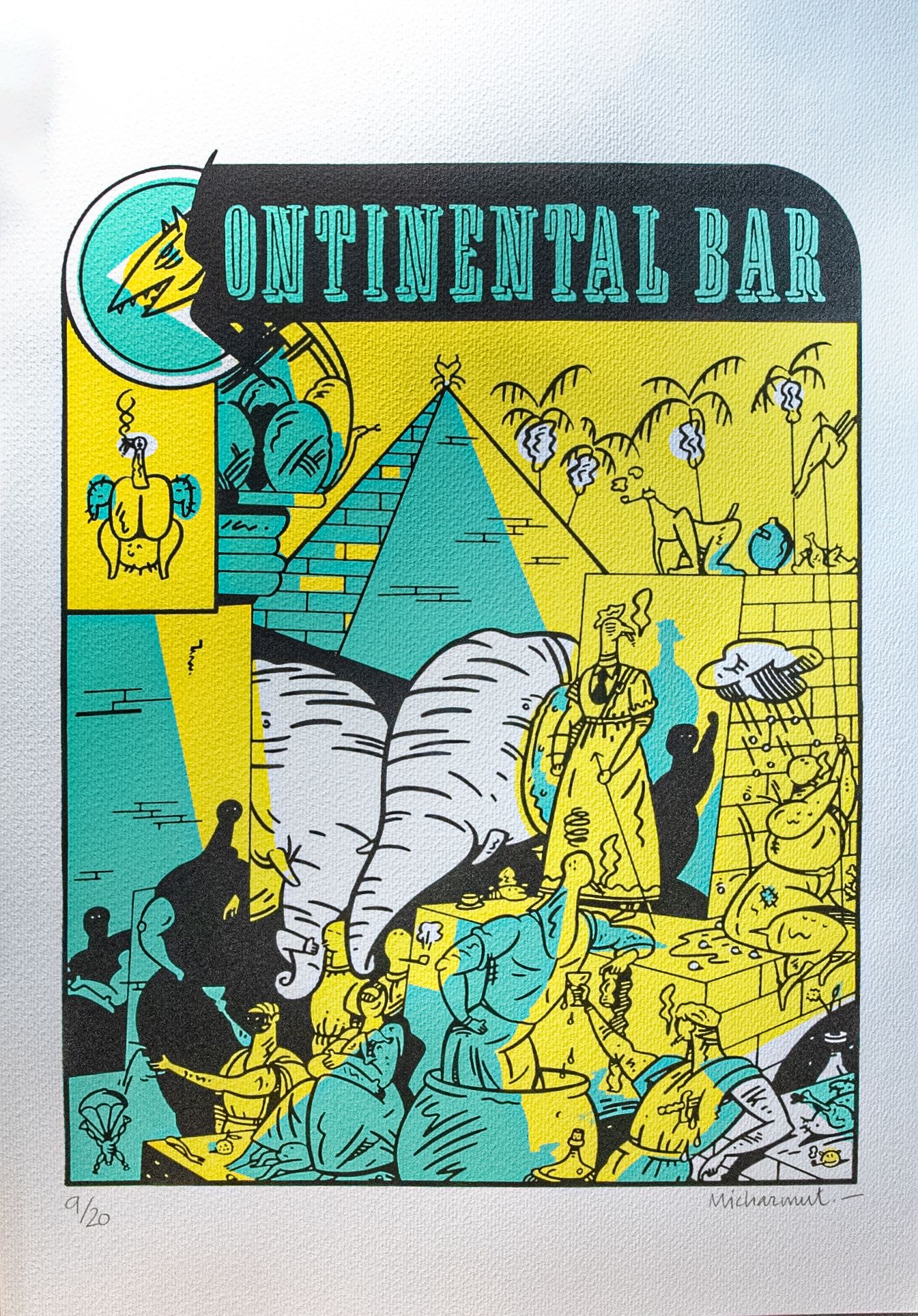

While the clubs pumped out their mix of new wave, post-punk, synth pop, techno and EBM, Valencian artists like Sento Llobell, Micharmut and Daniel Torres were emerging as pioneers of illustration, a generation later known as the Nueva Escuela Valenciana (New Valencian School). The owners of the city’s nightclubs looked to the creative vision of these young artists to create promotional materials to help keep the dancefloors packed.

Torres’ posters depict the slick outfits and funky hairdos paraded at the nightclub Metropolis. Today, he recalls how the key to this scene’s success was the doorway it opened to international music. “If you wanted to hear the latest music from Paris, London or Amsterdam, you’d go to Metropolis,” he says.

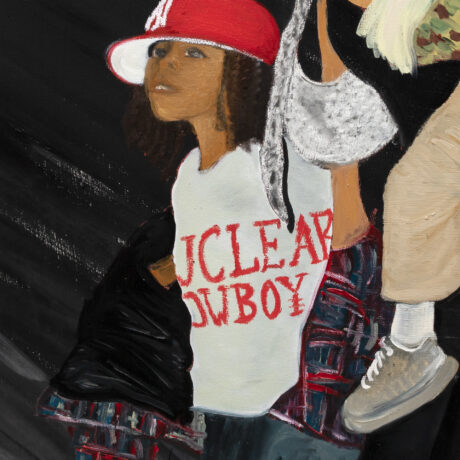

Torres and his peers of the Nueva Escuela were trailblazers of Valencia’s línea clara, a style of illustration deriving from Belgian ligne claire, pioneered by the likes of Tintin creator Hergé. The parties they attended were also gathering places for all sorts of quirky, creative types: “illustrators, designers, architects, musicians: we’d all see each other there,” says Torres. And the crowds weren’t lacking in style: images like El Hortelano’s poster for Spook vividly depict the various tribes that the sounds of Valencia brought together, from new romantics and psychobillies to punks and mods.

“The parties were also gathering places for all sorts of quirky, creative types. ‘Illustrators, designers, architects, musicians”

Artists and screenprinters Elisa Ayala and Armando Silvestre remember how the thrill of going out partying in Valencia went hand-in-hand with a new impulse in artistic creation. “There were so many different influences”, says Ayala, “and in the 1980s they exploded into a new way of making. There isn’t one rational style.”

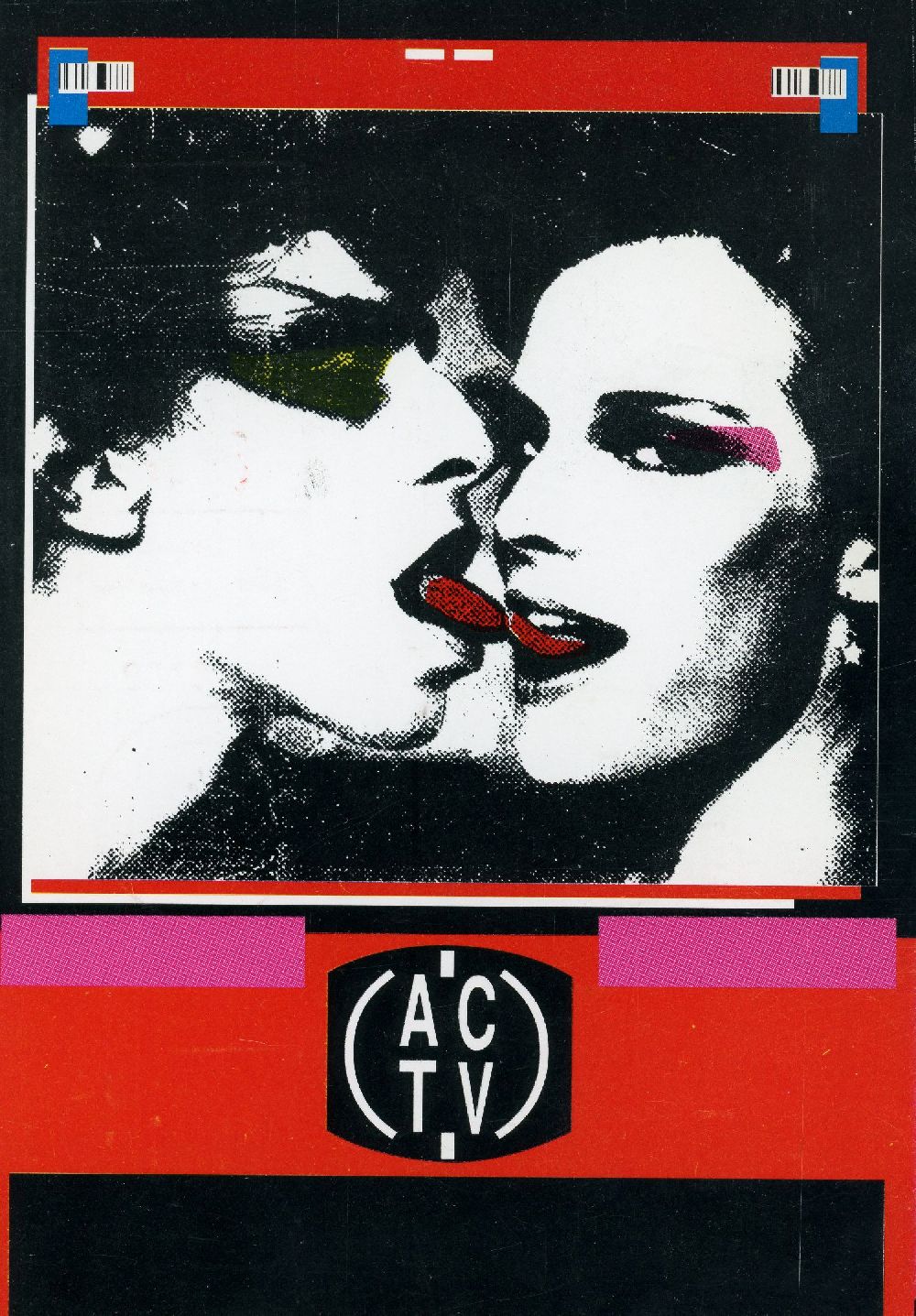

The duo’s one-off, handmade pieces for venues like Barraca, Chocolate and Espiral are a pastiche of distinct visual styles, from vintage pin-up girls and models in fashion magazines to pop art and comic strips, as well as transgressive twists on iconography of traditions like Semana Santa (the holy Easter week) and Valencia’s annual Fallas festival.

“In those days, if you wanted to hear certain types of music, you had to go to nightclubs. So the role of the DJ was really important”

Later works by Quique Company for ACTV indicate an evolution towards branding, with one established logo for the venue and a distinct look creating a unified sense of the venue’s identity. The images feel punky, queer and industrial, with an interest in the evolving role of visual technology such as video cameras and television.

By the 1990s, Valencia’s dance scene started becoming synonymous with rowdiness, drugs and bakalao: a heavy, commercial, high-tempo mix of electro and techno. It soon dwindled amidst a climate of panic around wild clubbing lifestyles, but despite this demise, La Ruta won enduring cultural relevance by pushing the boundaries of creativity and pleasure.

Following the end of Franco’s rule of Spain in 1975, such hedonistic cultural eruptions were products of the nation’s new-found liberty. “After 40 years of dictatorship,” explains Albertos, “people wanted to express themselves freely, in all creative and artistic aspects.” Inextricable from its political context, La Ruta captured a radical moment of change in Spanish history.

“After 40 years of dictatorship, people wanted to express themselves freely, in all creative and artistic aspects”

Often overshadowed by Madrid and Barcelona, this was Valencia’s moment to prove itself a dark horse of avant-garde contemporary culture. “What happened in Valencia is similar to what happened in Manchester,” says Haller. “In a provincial city, distanced from the national media focus, there’s more freedom and possibility to develop something original.”

In a curious revisiting of the past, IVAM’s exhibition and book unearth a buried part of Valencia’s history, casting fresh eyes on its otherwise muddied memories. While La Ruta made Valencia’s name as a clubbing capital, it also reveals it as the hub for a pioneering generation of visual artists that would be instrumental in the city’s fame. “There was a desire to bring to life what people had been dreaming of, to embody what we had in our minds,” says Elisa Ayala. “It was artistic on every level.”

Agnish Ray is a writer based between Madrid and London

Ruta Gráfica: Designs for the Sound of Valencia is at the Valencia Institute of Modern Art until 12 June, as part of World Design Capital Valencia 2022