An eye for a vulva. A housewife Madonna. A misshapen face. A wig of condoms. A bloody tampon. These are some of the resounding symbols from Les Rencontres d’Arles’s exhibition, A Feminist Avant-Garde: Photographs and Performances of the 1970s from the Verbund Collection, Vienna. On show at Arles’s annual photography festival through 25 September are more than 200 works by 71 women artists who created during the era in which the personal became political, and debates around gender, discrimination and equality raged in the public sphere.

Curator Gabriele Schor has staged the exhibition around five themes key to the feminist movement of the day: women’s reduction to wife, mother, and housewife; resulting feelings of confinement; the questioning of beauty standards and representations of female bodies; explorations of sexuality; and debates around gender roles and identities. “The exhibition title refers to ‘an’ Avant-Garde, one containing a multitude of feminist movements, diverse in age, nationality, and culture,” says Schor, who has attempted to consider the feminisms within the exhibition “in intersectional terms”.

While the dearth of intersectionality within second-wave feminism has rightly attracted criticism and caused cultural dissonance between its pioneers and the activists of today, the photographs on display here pay homage to the period in which radical feminist image-making entered the art world. Provocative, iconographic, and shot through with irony and biting wit, A Feminist Avant-Garde sheds light on the artists who broke ground with their experimental approaches to gender politics.

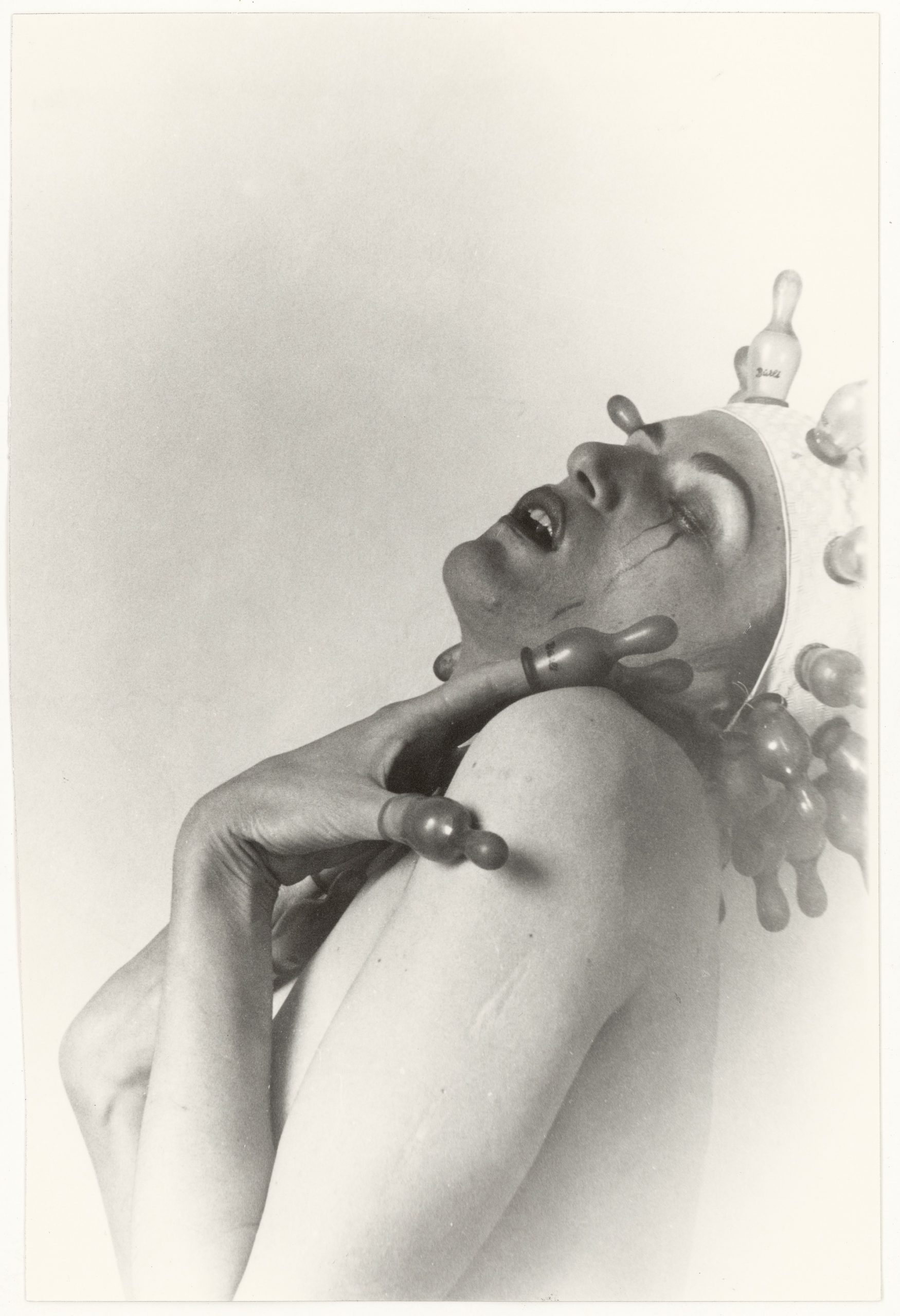

Renate Bertlmann, Zärtlicher Tanz, 1976

Irony is Renate Bertlmann’s weapon of choice. Since the 1970s, the Austrian artist has caricatured gender and sexuality with her absurdist photographs, sculptures and performances. In her tactile practice, she harnesses the suppleness of latex to highlight the malleability of masculinity and femininity: condoms and baby dummies are morphed into breasts and grafted onto wearable items, inverting phallic and maternal objects by turning them into erogenous zones. In this melodramatic self-portrait, Bertlmann poses in rapture (saint-like with her tears and halo of nipples) in a parody of eroticism and prescribed gender roles.

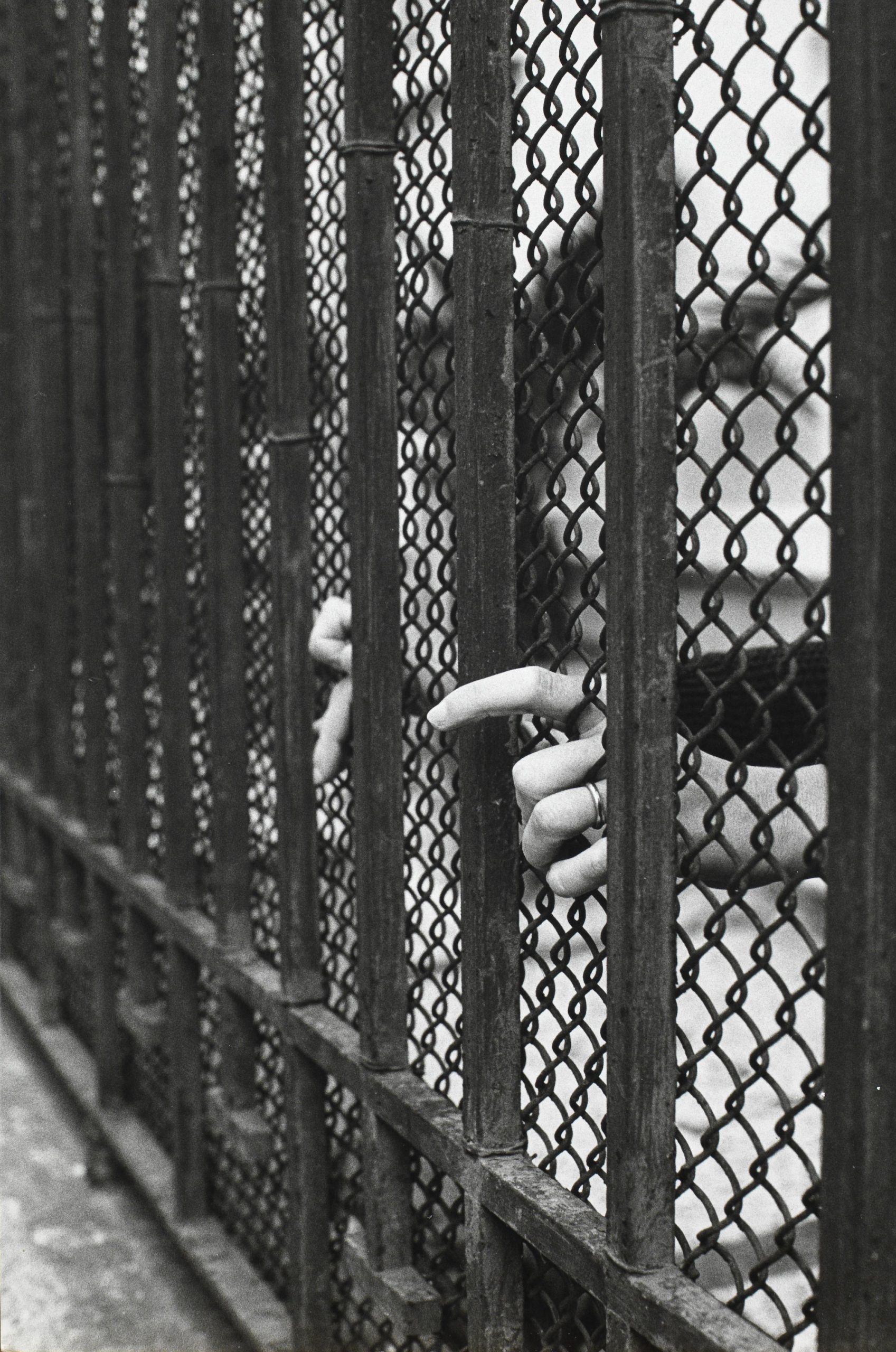

Helena Almeida, Estudo para dois espacos, 1977

Through her signature blend of performance art, photography, painting and drawing, Portuguese artist Helena Almeida created works that explore the push-pull of repression and emancipation. She often used her body, or fragments of it, as an object in her art, but resisted conventional terms of self-portraiture: “My body as a drawing, myself as my own work,” she explained. Ghostly hands reach through bars, chain-link fences and barbed wire in this series, which is explicit but no less stirring in its evocation of imprisonment.

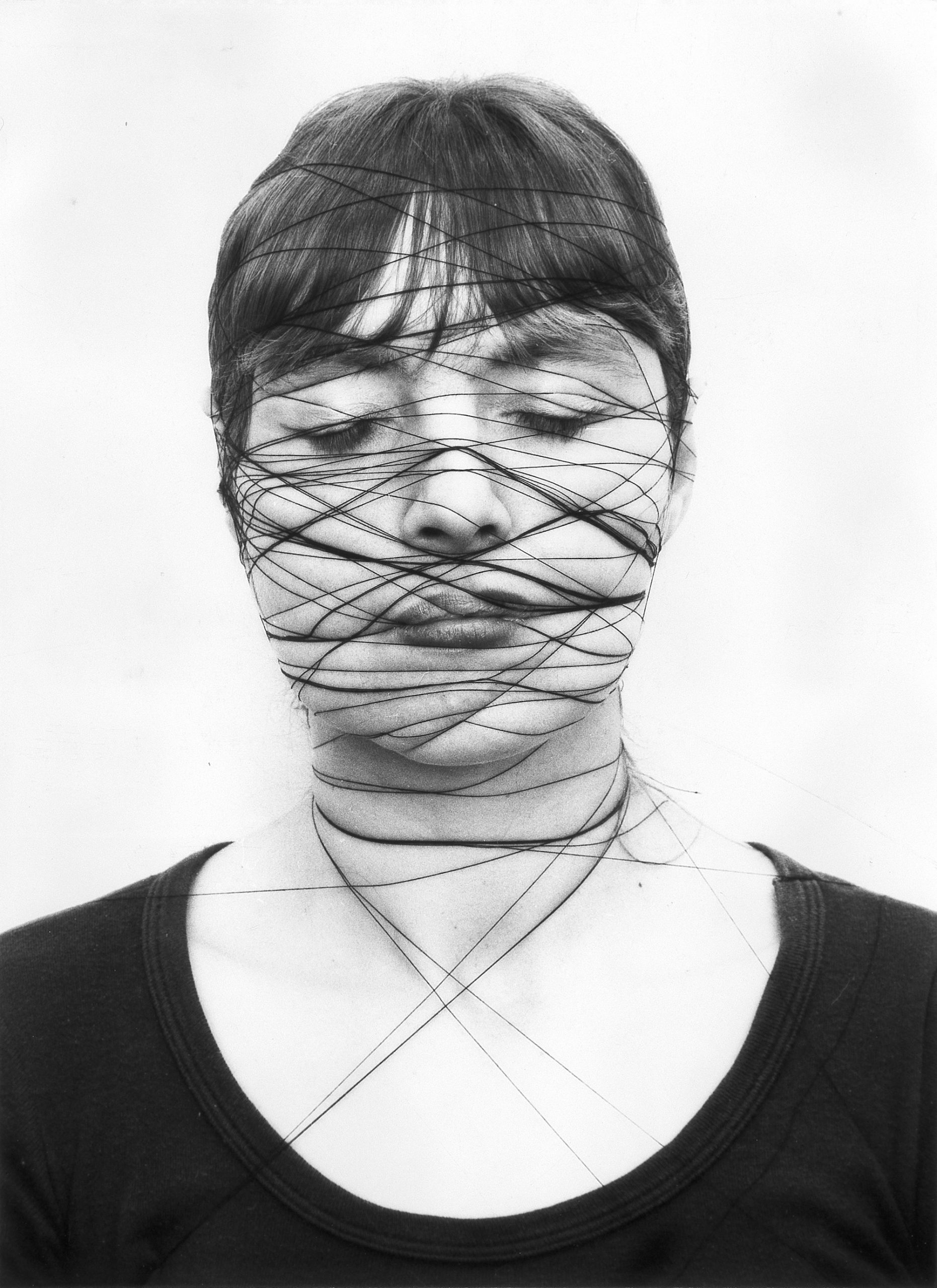

Annegret Soltau, Selbst, 1975

This uncomfortable image is from Annegret Soltau’s twelve-part photo-performance Selbst, in which the German artist was inspired to turn her drawings of women “that were enclosed, torn and split” into a “palpable experience”. She spun her face in black thread to the point of “deformation” and “pain”, before eventually reaching for the scissors and freeing herself. “It was created in 1975, which was a year of change for me as an artist as well as a woman in society: the private became political,” Soltau says.

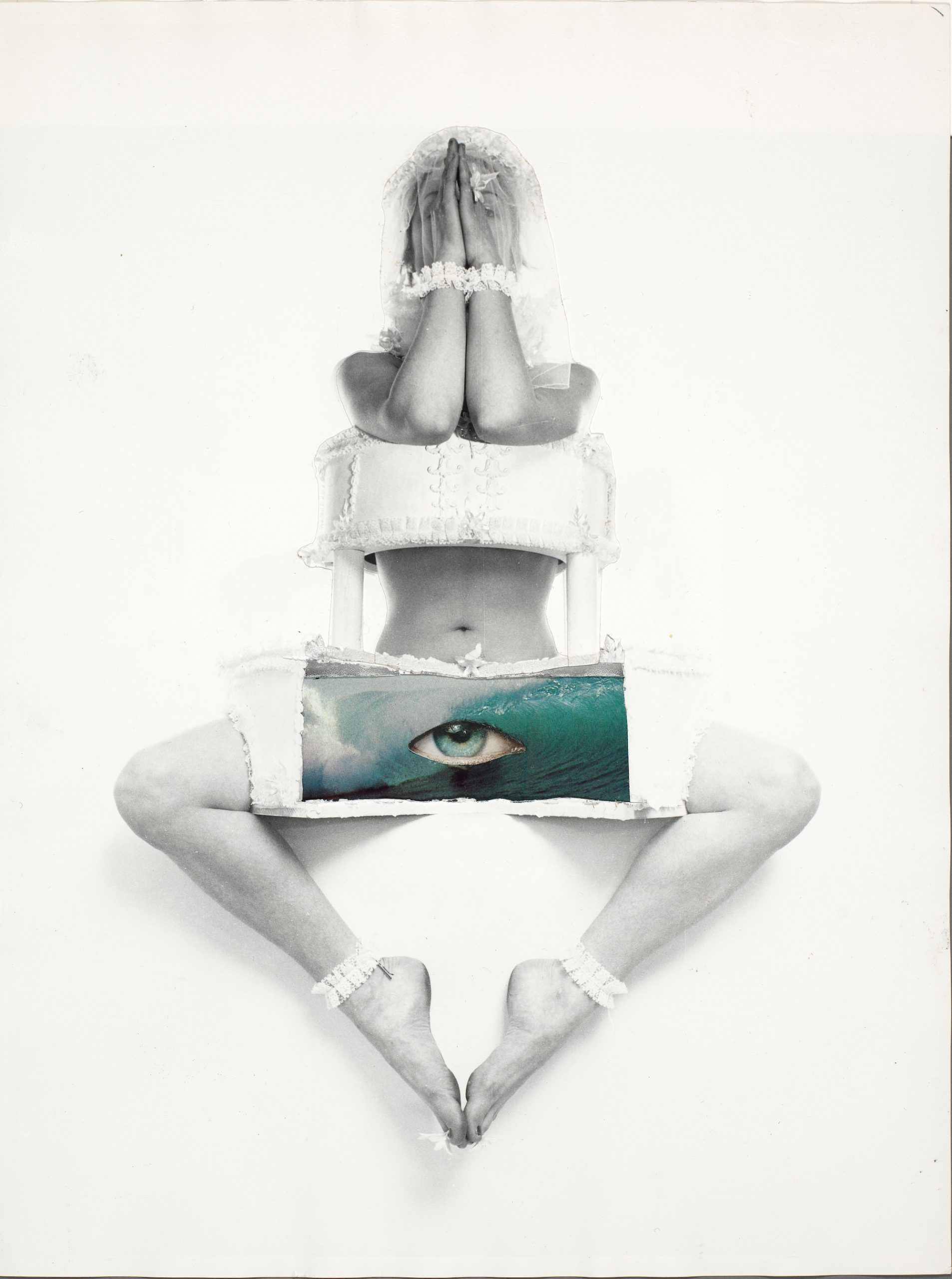

Penny Slinger, ICU, Eye Sea You, I See You, 1973

“I make artworks to bring the inside out and the outside in,” says British-born California-based artist Penny Slinger. Overlooked in the 1970s, her radical style of surrealist photomontage and provocative punk feminism has been rediscovered in recent years. This collage is from her Bride’s Cake series on food and eroticism, in which she posed as a bride/cake and created a “facsimile” of the traditional wedding album. While her face is obscured, the vulva becomes an all-seeing eye that watches the viewer: one of her acerbic symbols for revising the way in which women were seen and saw themselves. “It was both parody of a wedding ritual, and recreation from a woman’s point of view,” Slinger says.

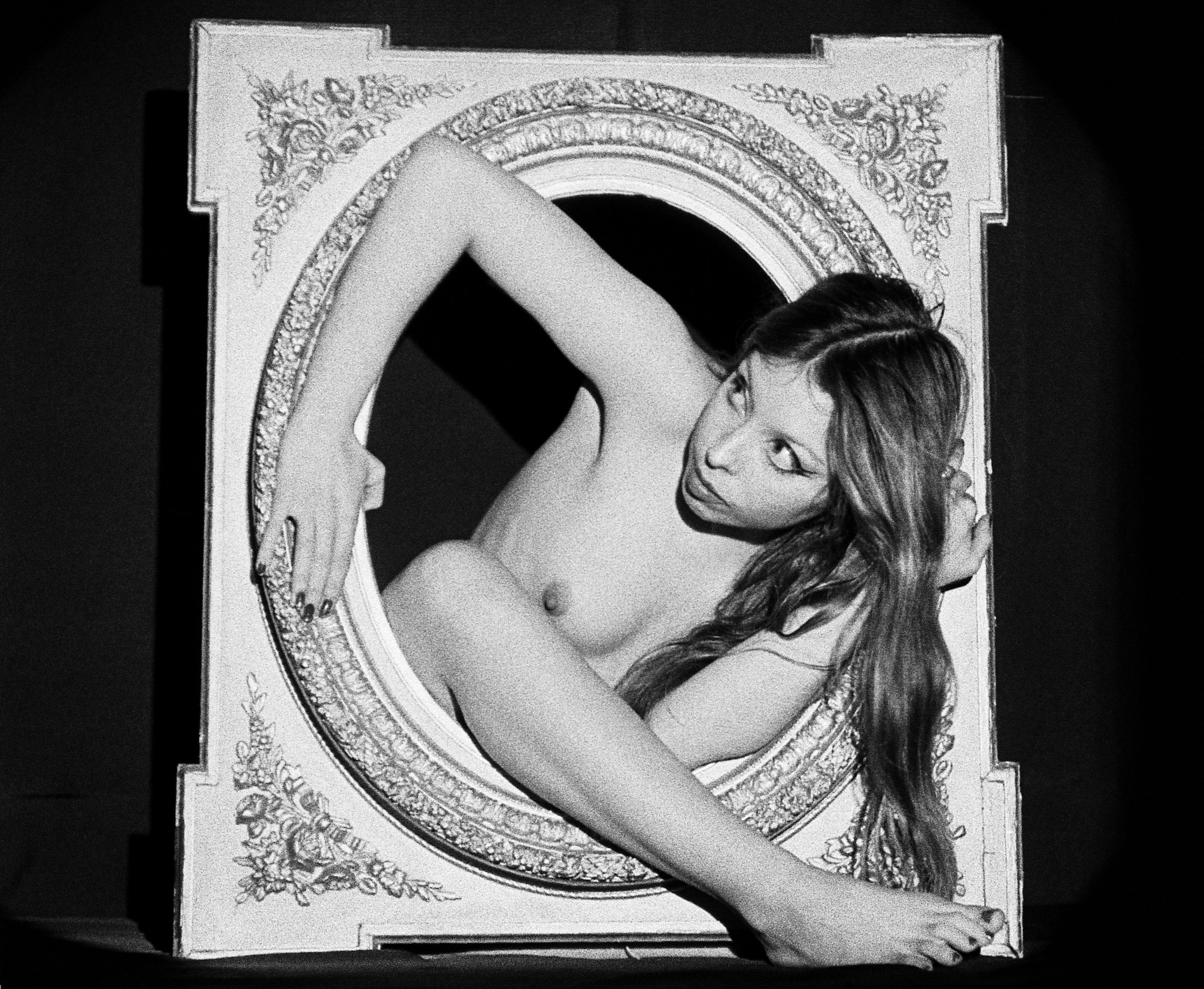

ORLAN, Tentative pour sortir du cadre à visage découvert, 1966

French artist ORLAN is known for radically changing her appearance through plastic surgery in order to “disrupt the standards of beauty”. But it wasn’t until the 1990s that she went under the knife, inspired by a life-saving ectopic pregnancy surgery in 1978,which she had filmed and remained fully conscious for. This early nude, Attempt to exit the frame with an uncovered face, can be viewed as a prophetic precursor to her later “carnal art”, which broke free from the white cube and transformed the body of the artist into an art object and site of debate.

Judy Chicago, Red Flag, 1971

Judy Chicago’s lithograph Red Flag is widely considered to be the first depiction of menstruation in Western contemporary art. It was created during her Early Feminist period (1970-74), in which she established the “central core” imagery now emblematic of her work. As Chicago explained in 1972, upon seeing the vagina as an “object of contempt”, “the woman artist takes that very mark of her otherness and by asserting it as the hallmark of her iconography, establishes a vehicle by which to state the truth and beauty of her identity.” More than 50 years later, the image of a bloody tampon being pulled from a vagina is still censored and tabooed.

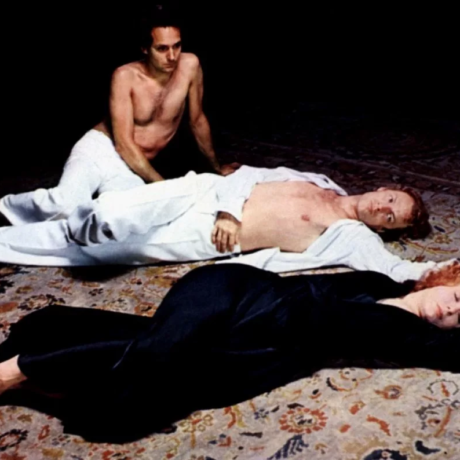

VALIE EXPORT, Die Geburtenmadonna, 1976

Avant-garde Austrian artist VALIE EXPORT’s photo-collage, The Birth Madonna, is a feminist reimagining of Michelangelo’s Pietà, a statue in St Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican City. Instead of holding the body of Christ in her arms, EXPORT’s subject sits empty-handed atop a washing machine, a blood-red towel gushing from beneath her. Michelangelo’s idealised depiction of motherhood is chopped up and confronted with the pain of childbirth and the crude realities of domestic labour. Rather than sealed in marble with her youthful beauty immortalised, EXPORT’s housewife is bodily and bleeding.

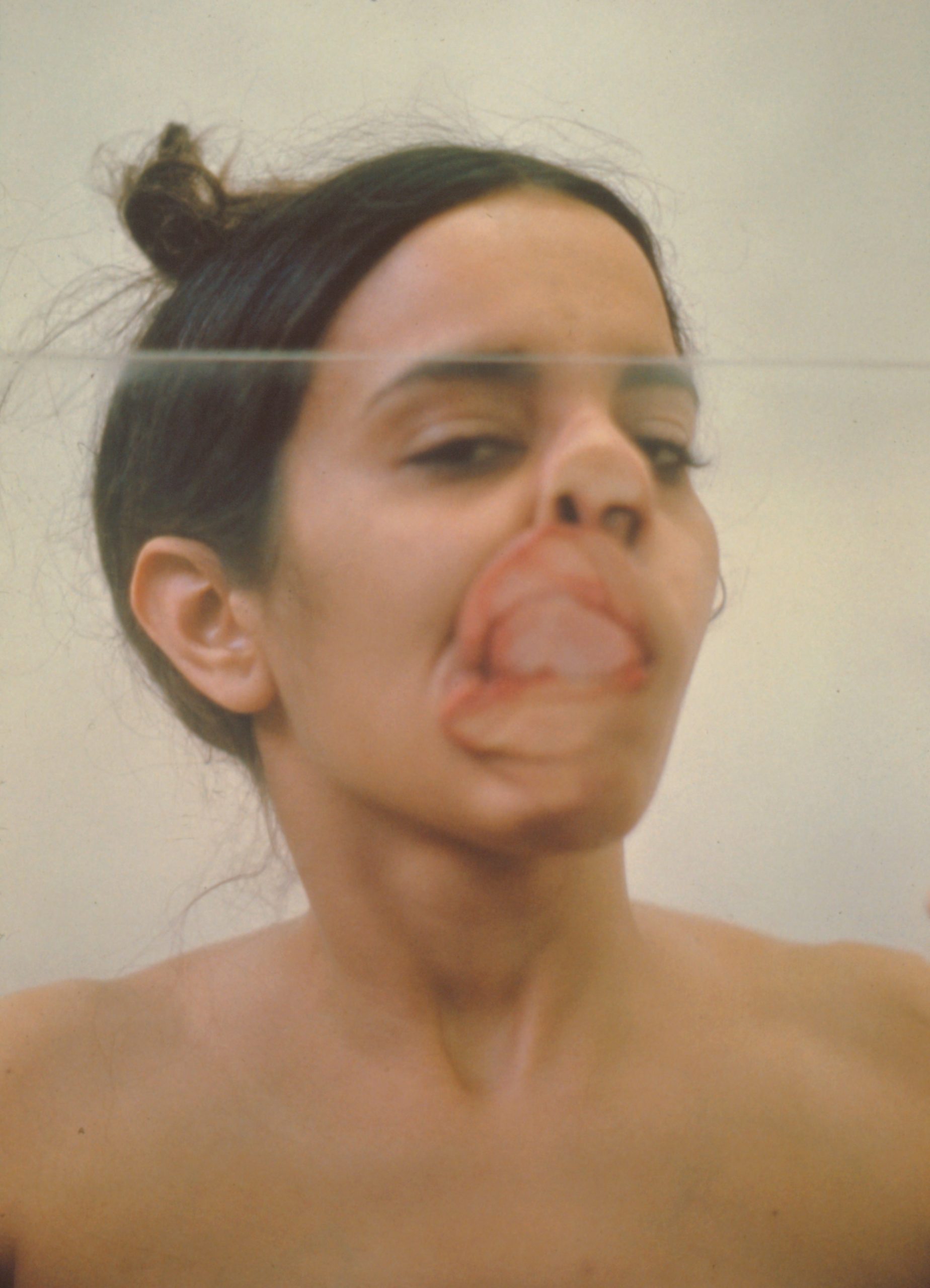

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Glass on Body Imprints), 1972

Created when she was a graduate student, Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta’s early performances confront themes of violence against women. She presses her face and naked body parts against a pane of glass in this disquieting series, documented through photography. Her distorted features evoke violent force and physical suffering. Simultaneously, in Mendieta’s reinterpretation of the grotesque, the deformation of the female form also signifies a rupture from the rigid expectations and pressures of the male gaze, something she felt keenly as a non-white woman in the US.

Lorraine O’Grady, Untitled (Mlle Bourgeoise Noire), 1980-1983

In 1980, conceptual artist and cultural critic Lorraine O’Grady arrived at a Black avant-garde art space in Manhattan wearing a gown made from 180 pairs of white dinner gloves and carrying a cat-o’-nine-tails whip decorated with white chrysanthemum blossoms. After smiling and offering the flowers to gallery-goers, she raised the whip (a reference to the slave drivers on Southern plantations) and lashed herself 100 times while shouting poems of protest against the exclusion of black people from mainstream art circles in the city: “Black art must take more risks.” With this “guerrilla invasion”, O’Grady’s fictional persona, beauty queen “Mlle Bourgeoise Noire” (Miss Black Middle-Class), made her debut, born from O’Grady’s anger at the racism and sexism that riddled the art world, as well as her own conflicted identity as the privileged daughter of Jamaican immigrants.

Madeleine Pollard is a Berlin-based journalist specialising in culture and current affairs

A Feminist Avant-Garde: Photographs and Performances of the 1970s from the Verbund Collection, Vienna is at Méchanic Générale as part of Arles Les Recontres De La Photographie until 25 September 2022