Nature is intrinsic to Florence Peake’s art. The collaborative body is her primary medium. She has choreographed naked dancers cavorting in six tonnes of wet clay, and performed with her girlfriend and artistic partner, Eve Stainton, evoking the aesthetics of the common slug through reciprocal vulva painting, as well as striking poses that represent rock formations and landslides, in a work about ecological crisis, queerness and marginalization.

“The practices that inform my work often relate to the flux of weather, geology, the migration and extinction of species, as well as these movements through landscape—the blending of the body with another landscape,” says Peake when we meet in a London café. She is a feisty presence, full of laughter and effervescence. The artist is about to head off on a retreat in Dorset’s Jurassic coastal caves with a movement practitioner called Helen Poynor. She does this periodically when she feels an urgent need to reconnect with nature. “I really like the full immersion,” she explains, “that sense of dissolving your own physical body into another physical body, like a rock face—I don’t know whether I even exist any more.”

Some of the caves are narrow and you have to slither along to get deep inside the cliff, where you might have a two-hour window before it gets submerged in water. It sounds alarming for the claustrophobic, but Peake finds it exciting. “I get turned on by the rocks on that part of the coast, it’s very much an erotic experience!” she hoots with laughter.

Peake’s refreshing openness and sense of humour are vital in her work with bodies, which challenges conventional attitudes toward nakedness, sex and sexuality. Her experimental performances can be embarrassingly candid, but they are rigorously underpinned by feminist and queer theory, as well as other fields of knowledge.

Her expressive use of the body is exemplified in her bold take on Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, which she presented at the Palais de Tokyo, Somerset House and the De La Warr Pavilion, where last year she had her biggest solo show to date. For the De La Warr performance, Rite: On This Pliant Body We Slip Our Wow!, five dancers slowly erupted from the wet clay and performed an anarchic, primordial celebration of liberation and sacrifice. The audience, seated in the round, were given ponchos for protection as clumps of mud flew. Peake was inspired by parallels between the current fractious world climate and that of 1913, when the premiere performance of The Rite famously provoked riots in Paris, as Europe stood on the brink of war. Peake’s gloriously messy version, which nods to forebears such as Carolee Schneemann, proposes the body as a political site for protest and change.

Peake’s work taps into concepts of pagan ritual and earth-mother goddesses, ideas once unthinkable in the cynical art world, but Peake has long been interested in shamanism and spirituality. Her 2015 performance work Voicings, for example, explored the phenomenon of “channelling”, or embodying spirits from another realm. “It always felt quite hard to talk about those kinds of ideas which do relate to feminized practices and feminism. That was very much something that was shamed or repressed in the art world.”

Never one to conform, Peake turned down a scholarship to dance school, preferring to bypass what she says is a rigid, sexist system that grants funding and positions of power to men. “As a dancer you’re trained to be this open, pure vessel, a neutral body for the choreographer’s vision to be imposed on, so it’s fucked up in relation to patriarchy, and psychologically very, very challenging,” she explains. Peake was more interested in somatic movement practices that privilege internal experience, anatomy and physiology over imitation of movement.

“I definitely think we consciously use vulnerability. It’s almost as a form of soft activism”

A breakthrough came when she was invited to work with radical feminist choreographer Gaby Agis, who had collaborated with the legendary Michael Clark. Peake herself has worked with a wide range of performers, not just across dance but live art, opera and theatre too.

“Now it’s all trans-disciplinary, but back then you had to choose which camp you were in. I was also studying being a rebirther [someone who uses breathing as alternative therapy] and was torn between being a therapist and an artist.” Coming from a creative family—her mother is the sculptor Phyllida Barlow, her father the painter and poet Fabian Peake, and her four siblings are all artists—art, fortunately, won the day.

After years of hard graft, Peake’s star now seems to be in the ascendant, boosted by her acclaimed De La Warr show. She and Stainton were commissioned to make a work for the 2019 Venice Biennale’s first-ever performance programme. The result was an audacious, sexually charged duet, Apparition Apparition. When I bumped into the pair during the festival, they were downhearted after receiving negative feedback, but by the time we meet again a few weeks later, Peake has bounced back with typical resilience. “Afterwards I was so glad we went there and kicked against the context and did something really vulnerable that engaged with people on that level. I felt really strengthened by it, but at the time it felt exposing, like I was walking around with no knickers on!”

Apparition Apparition is undeniably graphic and in your face. At one point, Peake jumps onto Stainton’s waist and thrusts her breast into the latter’s mouth, in an inversion of the Madonna and child. At another, Peake strides over to Stainton, in a bridge pose, and fixes her crotch on her girfriend’s mouth. But none of these actions feel gratuitous; they are integral to their portrayal of marginalized intimacy asserting itself in an oppressive heteronormative world. That world is, moreover, threatened by ecological devastation, which the pair convey by entwining their bodies into briefly triumphant sculptures that then collapse like a rock slide and slump apart. “Apparition Apparition was quite dystopian in a way,” agrees Peake. “There was this feeling of descent, this impending horror. It was using our relationship as a medium and very much speaking to the horror of this time and how we process trauma in our relationship.

The performance began with the artists, clad in thongs, clambering among audience members, inviting them to draw marks on their skin with felt tip pens. “It’s to do with marking oneself to make oneself even more explicit, this idea of the peripheral body being able to come into the centre, but it’s also like this preparatory device to do with the audience,” says Peake. “There’s lots of references, these slashes could look like self-harm, so there’s an emotional quality to those marks, but it can also look like hair or veins. It very much relates to anatomy. There’s something very pleasurable about doing it.” This intimate exchange between audience and artists does in fact generate a sense of euphoria for both parties, and sets up a sense of trust from the outset. It’s a non-verbal language, bypassing the limitations of the word.

Trust is essential to Peake. She was part of an impromptu discussion on consent at Tate Modern in June, after seeing French choreographer Boris Charmatz’s 10000 Gestures performed there, where twenty-five dancers leapt into the audience and manhandled spectators. “A lot was assumed of us as an audience and, for me, it really is to do with what’s happening in the world at the moment,” she says. “There’s trauma here in the UK with Brexit and I felt there was an arrogance.” That’s not to say she wants the field of performance to become sanitized. “I do believe you can really do wild, wild things with audiences, but I think consent is key.”

Consent is very much at the core of Peake’s solo practice and her work with Stainton. They craft it in different ways—by making eye contact to create a sense of active engagement instead of passive spectatorship or by breaking down hierarchies between performer and audience. Their own relationship, which began with Stainton working for Peake as a dancer, is a case of such hierarchical levelling. “Florence always worries that I’m going to turn around and do a #MeToo situation because bit by bit the structure of how were working changed quite dramatically,” jokes Stainton. The couple got together during a dry symposium where they were due to perform; when the screen went up, they were behind it, kissing. So their relationship has had a public dimension from the start and they have explored the theme of performed intimacy with their audience.

“I do believe you can really do wild, wild things with audiences, but I think consent is key”

The exuberant performance Slug Horizons (2017–present), for example, involves the pair decorating each others’ genitalia, closely surrounded by the audience, and executing a series of slow, unwieldy scissoring movements, keeping their crotches attached. In some iterations, they have invited audience members to participate in the decoration. “I definitely think we consciously use vulnerability. It’s almost as a form of soft activism,” says Stainton. “It feels quite political to be in a queer relationship as two women; to be seen in this vulnerable way.”

With Apparition Apparition the pair disrupt the spectator/performer divide by starting off in the audience, asking spectators if they would like to draw on their bodies. “It still felt quite rebellious to be caring,” says Peake. “I think there is something very confrontational about it, for someone to actually come and ask you how you feel about something.”

2019 was a good year for Peake in terms of visibility and success. She had a joint show with Tai Shani at Madrid’s Centro Centro running until February of this year; she is also working on a new choreographed piece that draws from both Slug Horizon and Apparition Apparition, with Stainton. But, like many artists now, she is more interested in creating nurturing communities than reaping fame on her own. Peake plans to explore the idea of care and empathy further, building on her previous work around collective expression of emotion. “I’ve always been quite interested in psychic phenomenon,” Peake explains. “What is empathy in terms of how we set up care and transference between each other? The body is this huge resource of intelligence, trauma and conditioning. It’s not neutral. I’m curious about that transference between psyches and how we can start to form some kind of telepathic and empathetic movement sequence with a group of dancers, and create a language.”

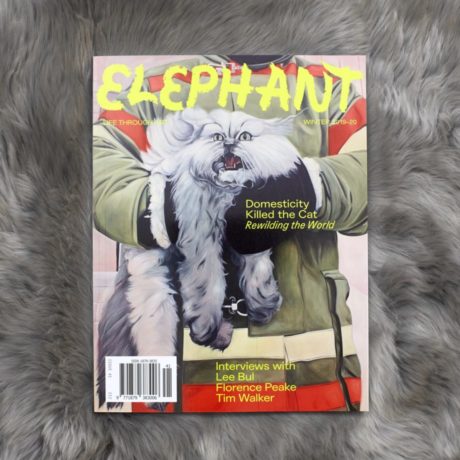

This feature originally appeared in issue 41

BUY ISSUE 41