The national pavilions at the Venice Biennale are probably the most famed aspect of the world’s oldest art festival. What began as a symbol of staunch nationalism, projecting a thoroughly Eurocentric outlook, has become a point for contention and celebration in equal measure. Increasingly, the teams behind these pavilions attempt to explore the multiple facets of cultural identity and notions of nationhood, all the while vying for attention within a pressure cooker of contemporary art spread across the Giardini, the Arsenale and further throughout the city. The prospect of exploring all possible national presentations is more than a little daunting. Here are five of the best examples we found.

France

The buzz from Laure Prouvost’s Deep Blue Sea Surrounding You spread quickly in the opening week, with lines snaking across the Giardini, past the pavilion’s traditional entrance, and through a basement door accessed via a rather overgrown path. Visitors are invited to take a mask (printed on the back of the introductory handouts), before being led into a surreal world of aquatic wonder.

Described as an “escapist journey”, this installation is meticulously crafted to resemble a liquid dream state, first with a strange room filled with ephemera suspended within a resin floor (as if you are walking on a rather junk-filled sea) and then with a fantastically bizarre film projected within a shell-grotto cinema, enveloping you in a mystical journey that follows fantastical humans as they make their own journey to Venice’s floating shores. In two adjacent rooms beyond, strange relics featured in the film reveal themselves, from a strange breasts sculpture formed of Murano glass to the young man silently clutching it.

United Kingdom

In what can only be described as the antithesis of a maximalist art show, Cathy Wilkes’s painstakingly restrained installation invokes hushed voices and careful consideration. This respite from the throng (with only a limited number of people allowed in at a time) consists of everyday objects such as a plate, plant pot or a piece of dirty lace.

They are placed among eerie sculptures that allude to androgynous human figures, some with swollen bellies, others with minimal expressive features drawn on their otherwise blank faces. The impulse to “get” this work is tempered by a complete lack of written information, which obliges the viewer to stop, look and draw their own conclusions—something that often terrifies the art world jet-set.

Ghana

Ghana’s national pavilion debut is a tour-de-force, presenting six artists rooted in “Ghanaian culture and its diasporas”. The space’s earthen architecture is designed by David Adjaye, with work presented in elliptical spaces that manage to feel like vignettes into individual yet interconnected worlds.

Ibrahim Mahama’s mixed-media installation A Straight Line Through the Carcass of History fills the air with the aroma of dried fish, while El Anatsui’s enormous bottle-cap-and-copper sculptures crawl across the walls. Meanwhile, paintings by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, as well as studio photographs from Felicia Abban—widely viewed as Ghana’s first female professional photographer—trace a lineage of joyous portraiture.

Canada

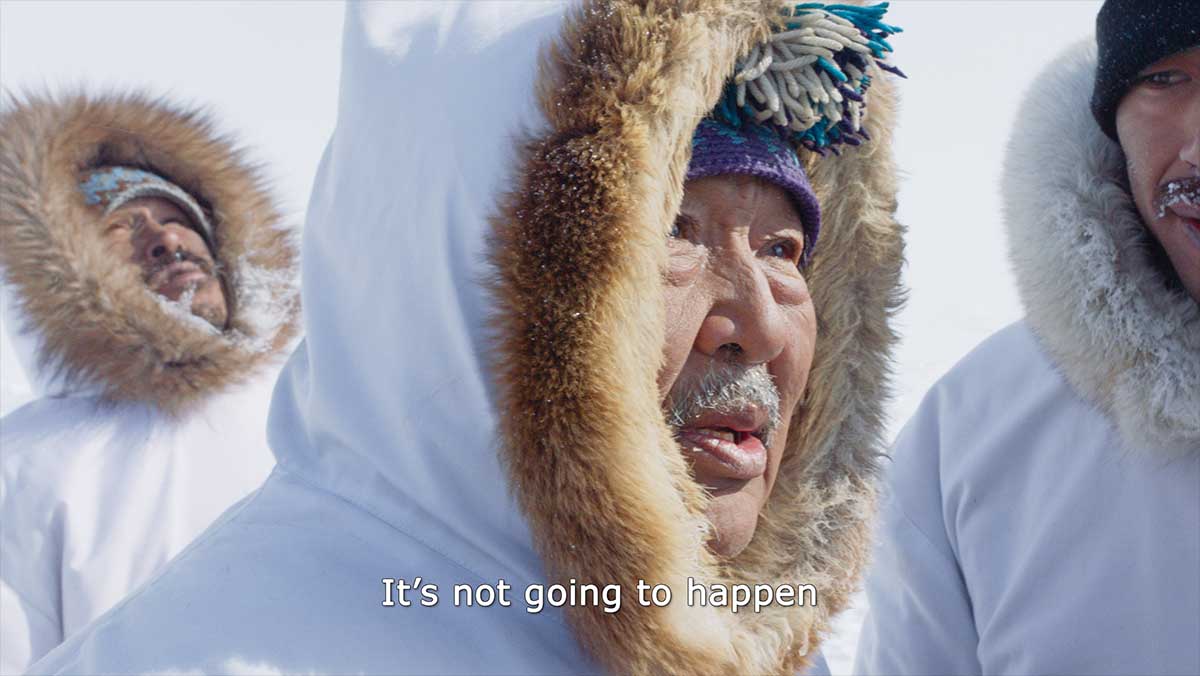

For the first time Canada has presented an indigenous group at the Biennale. The Isuma collective presents One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk, a film that recreates an encounter on Baffin Island in April 1961 when one Inuit family was ordered to move off the land.

It depicts the tense and fractured communications between the Inuit patriarch and a government official, with a dialogue that presents both the harsh realities of colonial oppression and occasional hilarious outbursts borne out of frustration. Along with this video installation, Isuma presents a comprehensive online catalogue that celebrates the United Nations’s International Year of Indigenous Languages, and Silakut Live from the Floe Edge, a series of live webcasts from the land around Baffin Island, which is under threat from mining companies.

Brazil

Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca’s filmic project Swinguerra has been in the making for several years. They have worked collaboratively with dancers who have embraced the swingueira dance phenomenon in Northeastern Brazil, which embraces cultural identity, expression and desire, and often offers an outlet for marginalized communities.

According to Wagner “Swingueira is a sort of updating of a set of traditions such as square dancing, the samba school and the trio elétrico [mobile sound systems], practiced autonomously and independently by youths who get together regularly in sports courts on the outskirts of Recife.” The resulting installation features portraits of the dancers in formation, and a film that captures the raw energy of these ferociously choreographed renditions in full swing, as well as their intense, collaborative practice sessions.