The art of sculpture is perhaps most vulnerable to clichéd ideas of hyper-masculine creativity. To sculpt is still often assumed to be solitary act of strength and violence, where a hard material is reformed through imposed will (which of course relates to a whole string of cultural histories concerning the patriarchy and colonialism). Barbara Hepworth, one of the few twentieth-century female artists to be suitably acclaimed during her lifetime, says it best: “[People] still think of sculpture as a male occupation: because, I suppose, they have a misconception of what sculpture involves. There is this cliché, you see, a sculptor is a muscular brute bashing at an inert lump of stone, but sculpture is not rape. No good form is hacked. Stone never surrenders to force.”

The Arts Council Collection hopes to dispel this narrative by presenting fifty female-identifying artists, including Hepworth, in a touring exhibition beginning at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Each of them have pushed the language of sculpture into entirely new territories. Here are just a few names who have blazed the trail.

Phyllida Barlow

Despite years as an influential educator as well as an artist, Phyllida Barlow had to wait decades to receive the recognition she deserved. Her expansive, all-consuming assemblages have since filled Tate Britain and the British Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, where she playfully reconsidered architectural space with massive sculptures born from utilitarian materials.

Barlow not only busts the myth that motherhood can stifle creativity but cites having children as a source of inspiration: “I became so fascinated by touching and feeling a baby when you’re cleaning or washing it, and all the wonderful, nonverbal contact you have with this creature, I think it got into the work in the form of a real exploration of touch.”

Anthea Hamilton

Anthea Hamilton steeps herself in research before realizing sculptures and installations that reference everything from disco to kabuki. In Elephant’s Issue 40, she explains that she constantly questions the act of looking and “how that looking has been informed”, which includes expansive interrogations of our visual history. For example, a recurring pair of Perspex legs, traced from her own body, reference pop culture icons Jane Birkin and Christine Keeler and the hyper-eroticized work of Allen Jones, thus raising questions around sexual agency and the gaze.

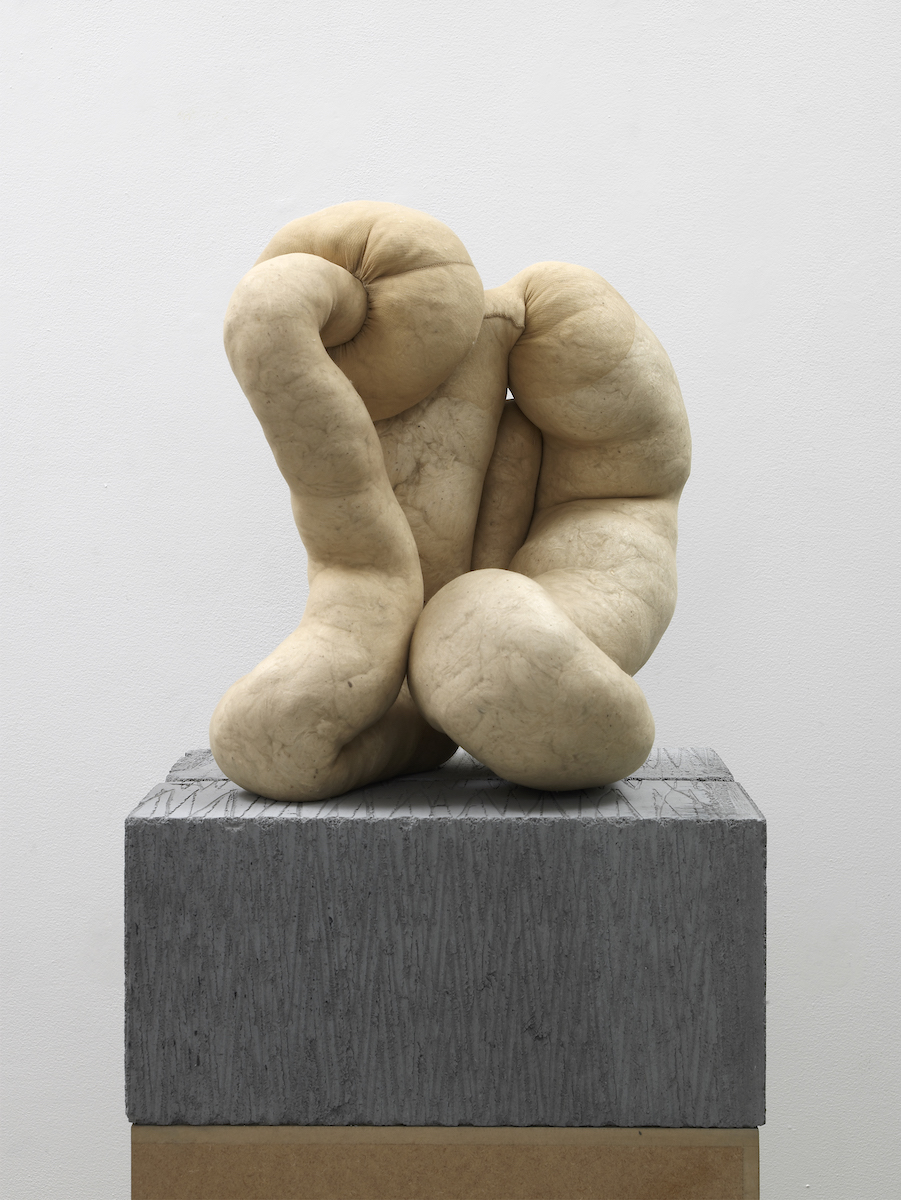

Sarah Lucas

As a member of the Young British Artists, Sarah Lucas upended the notion of what art could be, by utilizing sex and humour to provoke (who could forget her Self-portrait with Fried Eggs). Her radical sculptural style, created from every-day objects such tights, furniture and even cigarettes, has truly endured, with strangely sensual figurative forms offering entirely new readings of the female body.

Rachel Whiteread

Negative space has served as a key subject matter for Rachel Whiteread. While the notion of intangibility might seem abstract, she has solidified it, giving it emotion, memory and meaning through ambitious projects such as Ghost House, which saw the entire interior of a London home cast in concrete. Her work challenges the way we see spatiality, especially in close quarters, and reject the traditional notion that sculpting is an exercise in subtraction.

Rana Begum

When we think of sculpture we naturally think of dimensionality, but for Rana Begum, colour and light serve equally important roles. Her work draws on minimalist abstraction, urban architecture and traditional Islamic art, to question ideas of perception. Despite her broad collection of references Begum explains that, “I have found that gender and race are ever present, sometimes feeling like a determining factor in what I can do or how far I can go. I have had to push very hard in order for my work to stand alone and not be viewed through the lenses of gender, race or religion.”

Holly Hendry

Holly Hendry takes the unseen and overlooked aspects of our existence as a starting point, from chewed gum, industrial piping and rock strata, to our own internal fleshy workings. Her democratic approach to materials, which includes everything from Jesmonite and ash to silicone and eyeshadow powder, prove that a minimal, purist approach is not the only way to produce concise and conceptually engaging sculptural forms.

Liliane Lijn

Mechanisation is a key component for Lilian Lijn, whose “poem machines” were conceived as a way to “see sound”. Similarly, her spinning, illuminated cone-like structures serve as an antithetical approach to the bodily entrapment she felt as a young woman, who was trying to make art among the macho sensibilities of the Parisian surrealists. She identifies the cone as a feminine structure, but it has more to do with the mind than the body. As well as being a powerful artistic voice, she sought to rewrite the prevailing narrative by addressing gender imbalance via curatorial practice, in the exhibition Hayward Annual 1978, which was deemed radical simply for having more female than male artists on show.

Breaking the Mould: Sculpture by Women since 1945

An Arts Council Collection Touring Exhibition, at Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, dates to be confirmed