In the past few years, there’s been a remarkable uptake in exhibitions on queer subjects by large-scale artistic institutions. In London alone there have been group showcases like Queer British Art 1861 – 1967 at the Tate Britain (2017) and Kiss My Genders at the Hayward Gallery (2019), as well as the archive-driven Queer Spaces: London, 1980s – Today at the Whitechapel Gallery this year. Across the United States, and in New York in particular, this summer saw a roll-out of exhibitions in response to the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall Uprisings.

Queer cultural output, which has traditionally been censored, sidelined and ghettoised has officially made its entrance into mainstream institutions. At first glance, this feels like a win. Not only are LGBT+ perspectives being validated, but it represents a wider cultural shift in which queer aesthetics are finally being appreciated. Yet it’s hard to ignore the power dynamics at play. When larger institutions present the stories of marginalized groups, it can feel like a sidelined perspective is being offered up to the voyeuristic gaze of a public which wants accessed to these perspectives without necessarily giving anything meaningful in exchange.

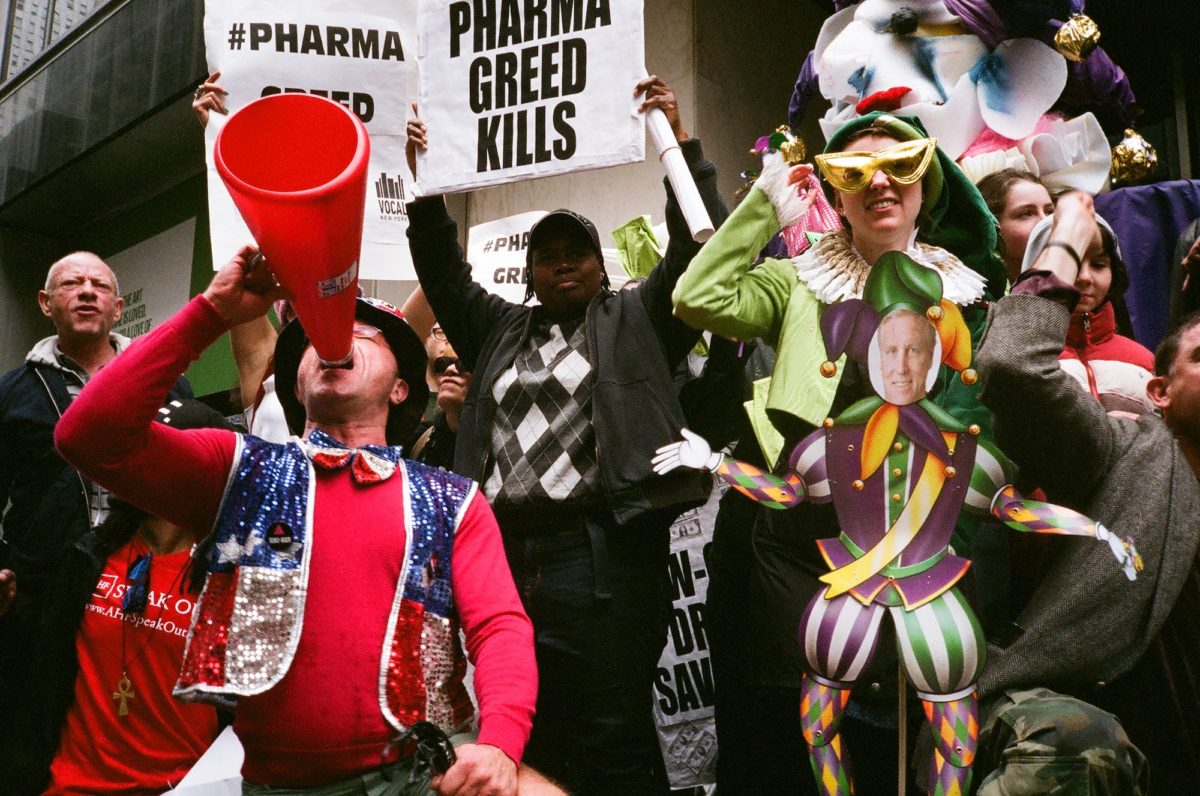

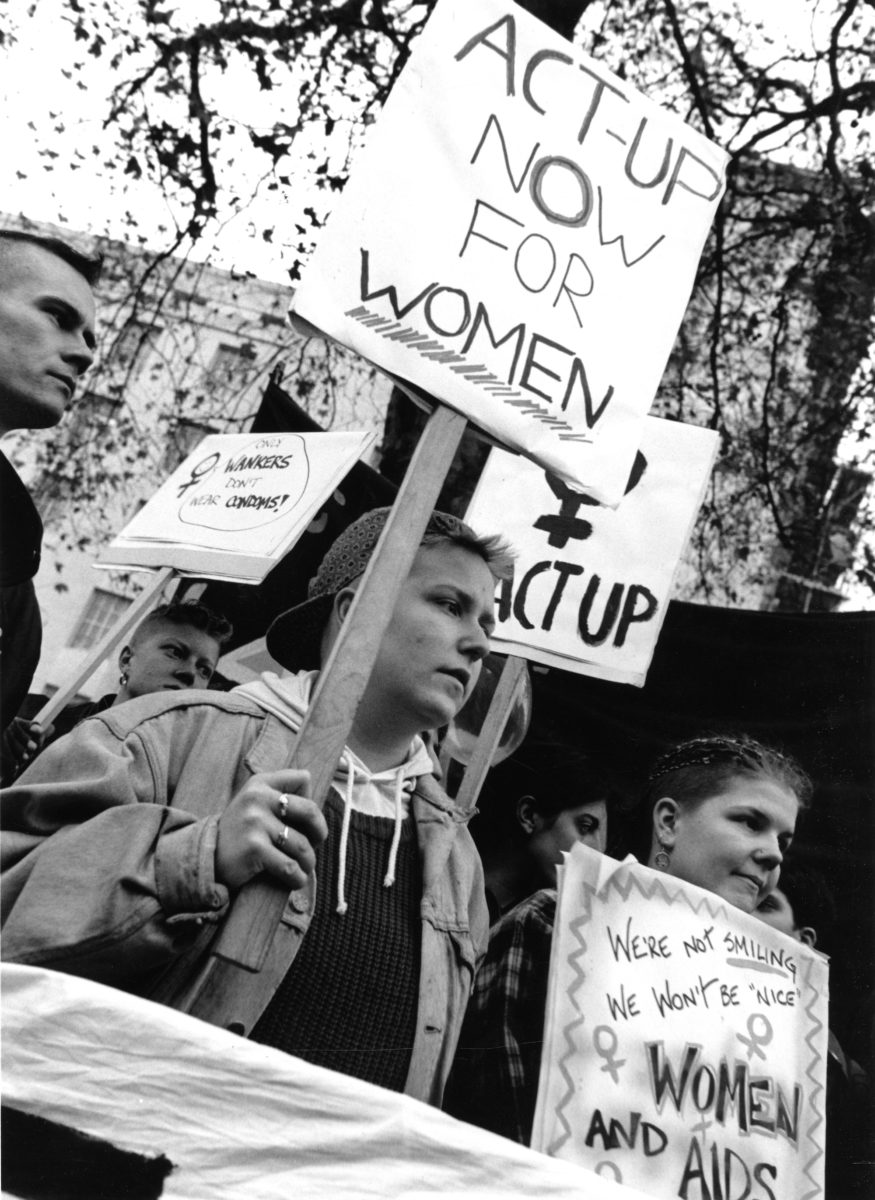

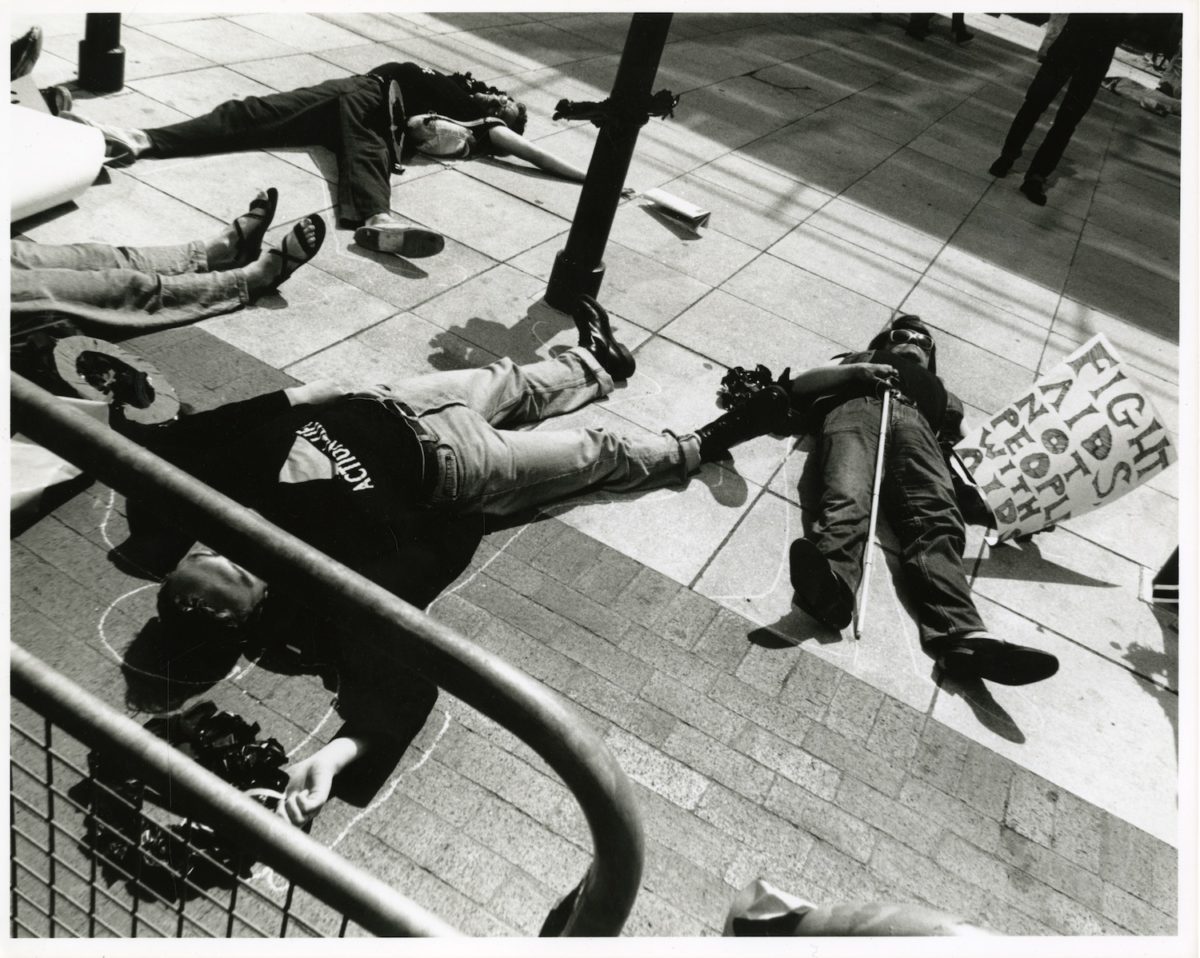

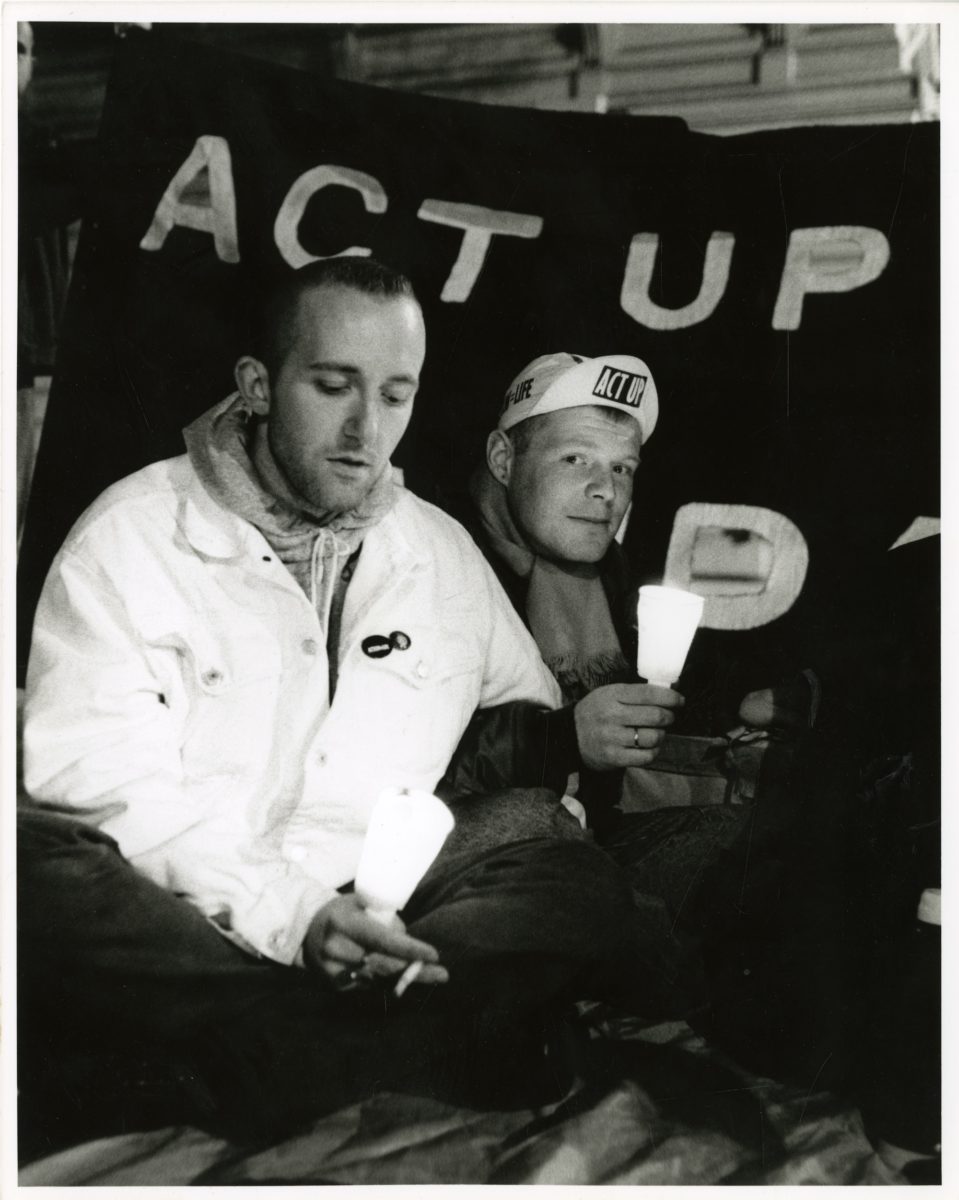

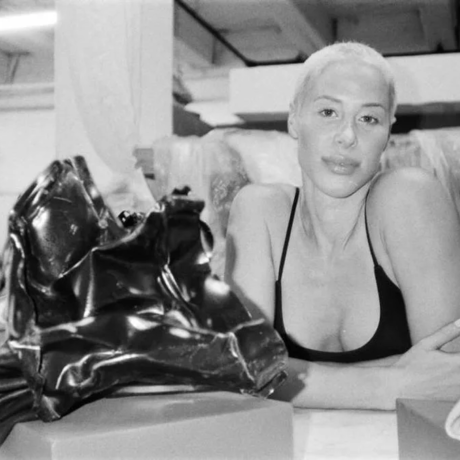

- Photos by Jacob Levi

“When larger institutions present the stories of marginalized groups, it can feel like a sidelined perspective is being offered up to the voyeuristic gaze of the public”

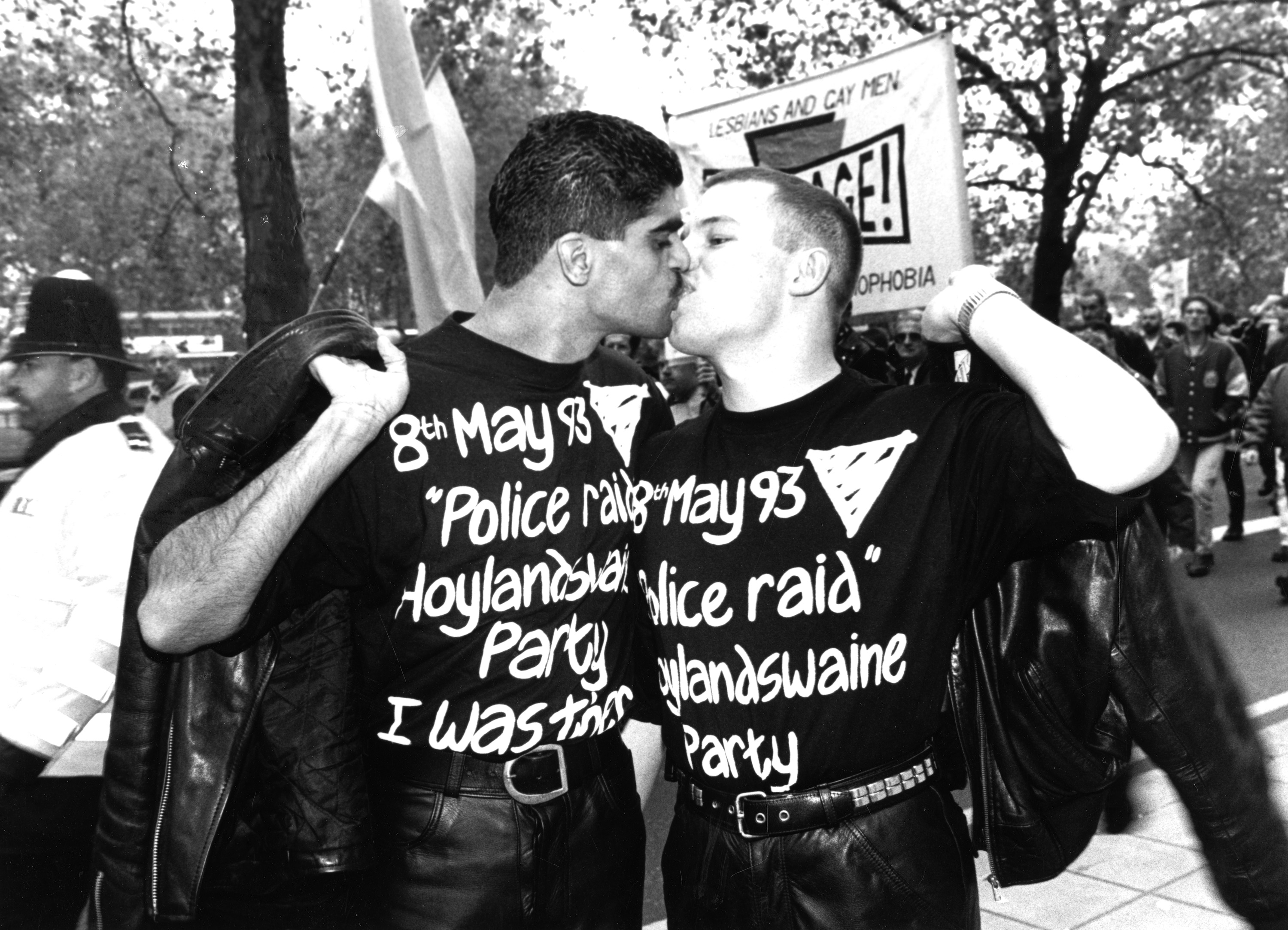

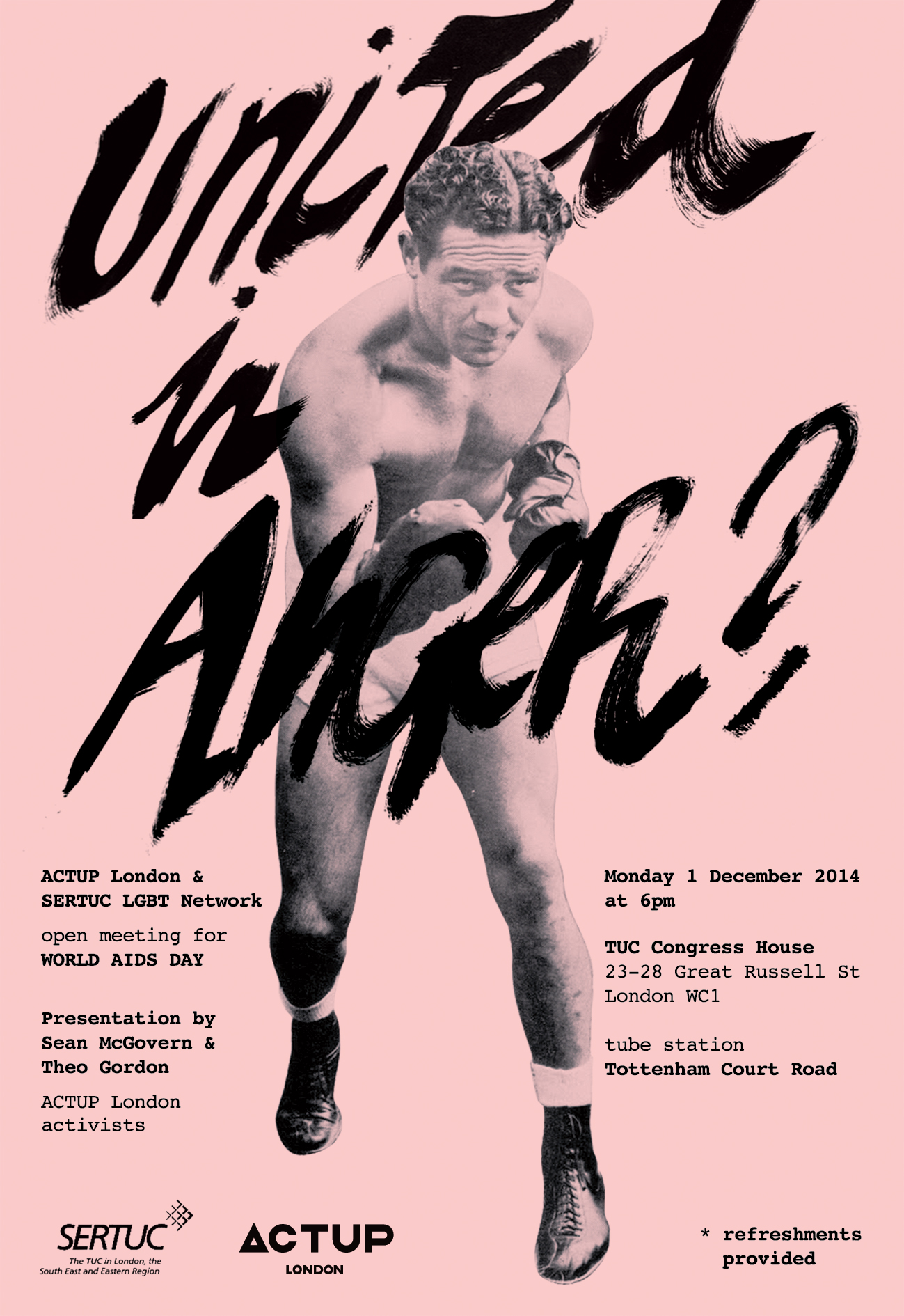

It was striking then, to see that East London queer bar Dalston Superstore would be hosting AIDS, SEX, QUEER POWER—”a herstory of Act Up London”— an exhibition presenting art and artefacts from Act Up London’s thirty-year-strong archive to mark World AIDS Day. Opened on 29 November and running until January 2020, documentary images of protests, placards and posters litter the bar’s walls. In a perfect symbiosis, this imagery is brought to life in a community space that itself — through its staff, customers, and the urban mythology that surrounds it — serves as a living and breathing archive of over ten years of queer life in London.

The cultural hub’s programming—running from club nights, to sexual health screenings, to a regular writing group—is generally diverse, but it still feels bold to hold an art exhibition here. To present this narrative of queer activism within a queer space enables the LGBT+ community to remain in control of their own histories, suggesting that they don’t need any institution to validate their stories and legacy. Moreover, the choice to house these documents of queer struggle in a traditionally queer space feels like an important recognition of the role of LGBT bars and clubs, both in building community and consciousness-raising.

The show’s curator, Emma Kroeger, explains that Dalston Superstore is intended to feature as a part of the exhibition, as well as its venue. “The work is understood as a living part of the venue, and it is an opportunity to reflect not only on the significance of the history being told, but also the importance of the space housing it,” she explains. “Without queer venues as cultural hubs, so much of this activism would not be able to take place.”

Kroeger explains that queer art doesn’t necessarily have to be shown in specifically queer locales, but there is a difficult balance that has, as of yet, not been fully addressed. On the one hand, she notes that seeing queer art in mainstream institutions does represent progress. “I think that it is really important that queer stories are finally being told by established institutions,” she says. “There is something really meaningful about seeing queer work that has historically been relegated to basements and underground spaces finally being recognized as important by the art world at large.”

However, she concedes that it’s important to be cautious, as galleries can sometimes act to consolidate pre-existing power dynamics. “I think there is still an implicit classism in the idea of this kind of subversive art being validated by the establishment. Why is it necessary to be validated by the establishment, and what kind of stories are being privileged?”

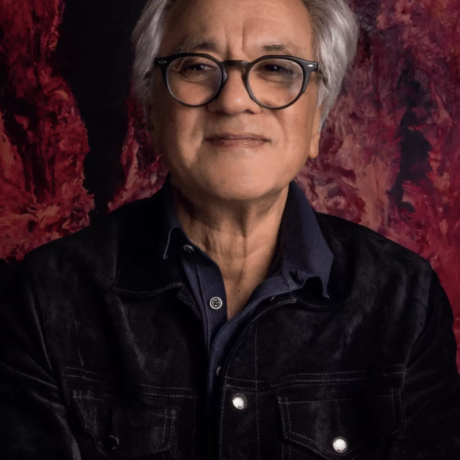

It’s inevitably difficult when queer narratives are represented in mainstream galleries, for a general public that isn’t necessarily familiar with the breadth of LGBT+ experiences, as some of the nuance can be lost. “It is often the case that minority voices are being silenced or ignored, and there isn’t a sensitivity to the complexity of the queer story,” Kroeger points out. As it stands, the artists most strongly associated with “queer art” are figures like Andy Warhol, Catherine Opie, Robert Mapplethorpe and Keith Haring—rather than the trans or POC voices whose voices and vital contributions shouldn’t be overlooked. As Kroeger asserts, presenting queer art in queer spaces could help correct some of this. “Having exhibitions in our own spaces means that we are in control of our own stories, and the ways in which they are told.”

Yet how feasible is it for queer art to step away from the gallery structure when gentrification means that queer spaces—saunas, bars and clubs—are closing at alarming rates? The comparative longevity of art institutions make them a more stable space for exhibiting and canonizing queer art, but this can only be done in a respectful way when galleries demonstrate an awareness and understanding of the queer structures and social spaces that inform the art produced by LGBT+ artists.

“To present this narrative of queer activism within a queer space enables the LGBT+ community to remain in control of their own histories”

With Queer Spaces: London, 1980s – Today – Gentrification, Sex and Queer Disruption, an exhibition that ran from April to August 2019, the Whitechapel Gallery arguably did just that. Drawing from the archives of different queer spaces across London, the show interrogated the ongoing status of the queer bar and gay cruising spots in LGBT+ communities, as well as the relationships between the gallery and the queer space.

Whitechapel Gallery Assistant Curator, Cameron Foote explains that the exhibition was a part of a sustained effort to bring greater diversity to the gallery’s programming through archive-focused shows. “Since 2009, Whitechapel Gallery has hosted an ongoing programme of exhibitions based around archives,” Foote says. “This show was part of a strand that brings lesser-known exhibition histories, as well as histories related to censorship, political oppression and feminist and LGBTQ+ struggles, to the forefront.”

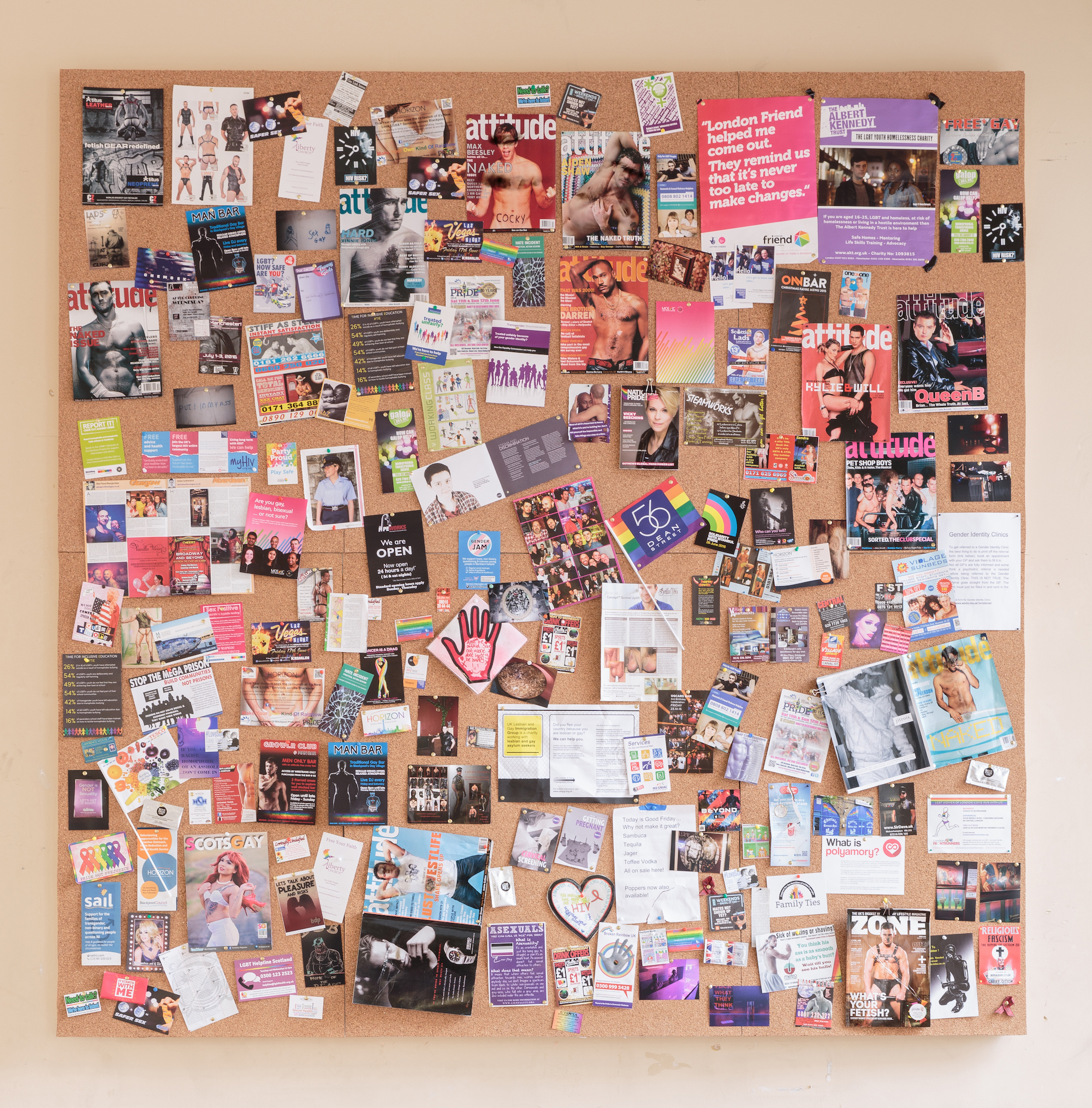

The curatorial approach set out to avoid reinstating a power dynamic in which a larger institution “saves” or preserves stories which have previously been overlooked. Rather, there was a more even-handed approach, and certain works were chosen for their ability to trouble the divisions between the gallery and the queer social space, flattening the distinctions between “high” and “low” culture in the process. In particular, Queer Spaces housed two works by Prem Sahib, whose work deals with an explicitly tactile, gay male sexuality and often makes reference to gay bathhouse or sauna culture. A work from Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings’s @Gaybar project, which brings together flyers, gay magazine cuttings and health information brochures from 170 gay bars across the UK, also featured.

“I think there is still an implicit classism in the idea of this kind of subversive art being validated by the establishment”

- Left: That Ray. Right: Soroya Marchelle. Both photographed at the Royal Vauxhall Tavern in 2018 by Léa L'attentive. Courtesy Léa L'attentive

Foote hopes that these works, alongside community events, “break down some of the hierarchies that can feel present in museum and gallery spaces.” Yet even if these boundaries do exist, the gallery space is perhaps able to offer a greater sense of oversight, where more are able to appreciate the full impact of queer art, social spaces and culture. What queer bars lack, particularly in times of gentrification and if they cater to women or BAME groups, is the funds and resources to do this on their own.

As Foote puts it: “While queer spaces in London and beyond provide a vital place for LGBTQ+ people to find community, socialise, and explore identities outside the mainstream, galleries and archives provide the unique and essential role of housing and highlighting in one place the cultural impact of queer spaces, past, present and future.”