In a post-pandemic world, our homes are no longer our homes: they’ve been forced to become classrooms, art spaces, recording studios, gyms, DJ booths, TV quiz show sets and so much more. Working from home doesn’t just mean tapping away at a laptop and a company-wide frustration with clunky remote servers. However, there’s one bunch of people for whom the new WFH is nothing new at all: those creating self-recorded music.

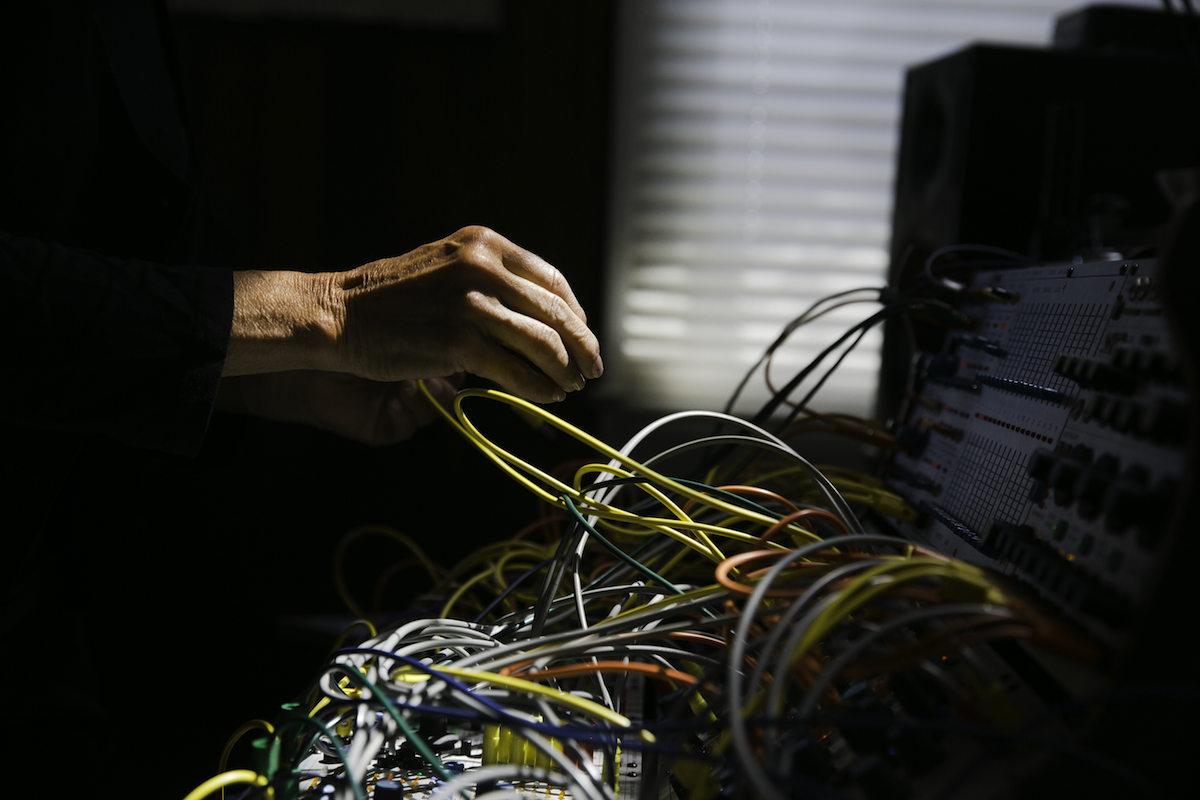

Eschewing the acres of knobs and dials of professional recording studios, these often obsessive types have reconfigured their living spaces into the setups that work for them. The way they do this is as varied as music itself: at one end, there’s the historic simplicity of a four track recorder (today’s equivalent might be a Mac laptop, with its free copy of Garageband and a single-input audio interface); at the other there are the homes that have the luxury of space to accommodate vast, sprawling masses of wires crisscrossing room-sized modular synths that look more like an old-fashioned telephone exchange.

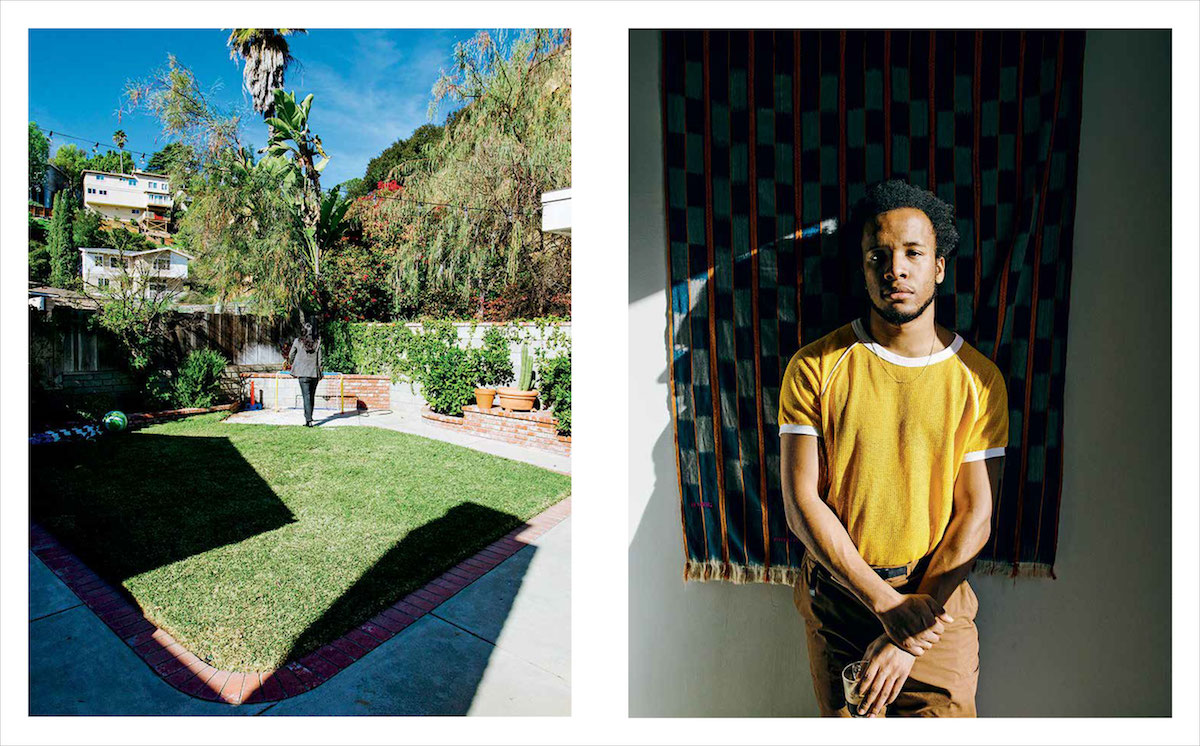

- Mirror Sound, spread

“We can learn creatively from others and ourselves through curiosity”

A new book by musician Spencer Tweedy (the son of Wilco frontman Jeff Tweedy), Grammy Award-studded designer Lawrence Azerrad (who heads up Los Angeles-based LAD Design) and photographer Daniel Topete looks at the multifarious ways in which contemporary musicians record at their homes across America. Titled Mirror Sound and published by Prestel, this gorgeous volume features photographs of 27 artists including Sharon Van Etten, Mac DeMarco, Yuka Honda, Bradford Cox, Eleanor Friedberger, Emitt Rhodes, Lætitia Tamko (Vagabon), Blake Mills, Cautious Clay, Dan Deacon, Juana Molina, NNAMDÏ, R.A.P. Ferreira, Ty Segall, Tune-Yards and tonnes more.

As well as focusing on the making and recording of music, this book is also about the inherent creativity of using space, and the joyful discoveries that are born of the limitations that come from that space also being a home. “It’s not a book about interiors per se but our environments and where we choose to create—there is a creative consideration and effect in that,” says Azerrad. He adds that the book also gently underscores the fact that certain impulses are shared between all artists, whatever their medium: “There’s an itch to push what is possible, a trust in facing risk, and an intention to share the outcome with others… We can learn creatively from others and ourselves through curiosity.”

The subtle links between music and design aren’t just apparent in how musicians modify spaces, but in their tools and the “hacks” they employ. The late cult psych-pop hero Emitt Rhodes, for instance, constructed an entire rig from paper plates. “In this kind of problem solving there is essentially design,” says Azerrad. “Creatively figuring out solutions to challenges on your own terms is design—just without the slick visual skin.”

The trio behind the book has been very smart with its selection of subjects: not only is there a genuine breadth of sounds, genres, artists’ backgrounds and geographical locations across the US; each musician presents an entirely unique approach to reconfiguring the domestic into makeshift (or indeed rather slick) recording studios. There’s a deft balance between lifestyle-leaning photography of charmingly eccentric people in their Moog-packed living rooms and shots that nerd out on guitar pedals, compressors and all (“we consciously didn’t want this to look like a music tech book,” says Azerrad).

It isn’t just about celebrating the “bedroom producer” either—a term that’s become ubiquitous in recent years, largely thanks to Soundcloud: the authors are keen to point out that self-recording does not equal lone wolf. More often, it means a good excuse to hang out with likeminded friends. Indeed, so much of the sort of music presented in the book is the product of just tinkering about, rather than calculated record label appeasement or chart-baiting.

But that’s not to say that much of the beautiful strangeness in the sounds many of these artists produce isn’t down to that amorphous but palpable atmosphere that emerges from voluntary isolation. “I think that the feeling of solitude is what makes my writing and recording sound the way it does,” says Melina Duterte, known better as multi instrumentalist Jay Som. “I guess the best work comes out of you when you’re in your favourite environment, in the environment that you feel best in.”

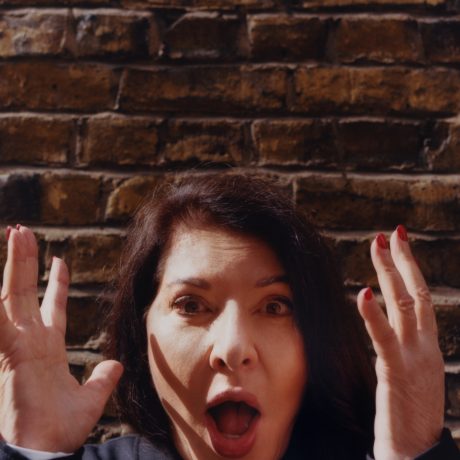

- Mirror Sound, spread

“I think that the feeling of solitude is what makes my writing and recording sound the way it does”

While Mirror Sound is squarely focused on music-making, the themes it delineates—inventive domestic modifications, working outside of conventional means, the idea of creative independence—are relevant across most artistic media, particularly right now as we vacillate between various levels of Covid-19 lockdown.

A key aspect is also the beauty of art that’s born of mistakes, limitations or both. As Carrie Brownstein of Sleater-Kinney (and more recently, co-star of TV show Portlandia) writes in the book’s foreword, “It’s a journey from the desultory to the intentional and back again: learning in order to unlearn.”