In Jonas Mekas’s memoir I Had Nowhere to Go, he writes: “The twentieth century has produced millions of refugees, exiles, and stateless Displaced Persons.” The avant-garde filmmaker’s chronicle of his journey–fleeing his native Lithuania, being imprisoned in a Nazi forced labour camp, then drifting through Europe and eventually America as one of millions of Displaced Persons (DPs) after the war–is a central story to this year’s Documenta. The sprawling exhibition, this year itself displaced between Kassel and Athens, reveals a curatorial team grappling with political and social parallels between Germany and Europe’s past and present. Led by artistic director Adam Szymczyk, the curators have spent years carefully mining the histories of war and the imprint these have left upon communities. Themes such as immigration, the refugee crisis, and political and economic instability are addressed head-on, but there are also moments of subtlety and quietness which deal more abstractly with what it means to be a body or an object that is forcibly moved.

Mekas in fact spent time in Kassel in a DP camp established there, and his presence lingers throughout the city. A new feature-length film by Douglas Gordon, also titled I Had Nowhere to Go and screened off-site in a multiplex cinema, features Mekas reading from his memoir with a largely blank screen. Here, the physical dispossession experienced by Mekas is expressed through a dispossession of the senses, where the expectation of cinema to portray an image is ruptured. The viewer’s imagination has to work hard to create imagery that fills in the gaps, while the narrative jumps forwards and backwards in time, creating a further sense of precariousness. Gordon’s film questions how we either remember or imagine war to be, and how lives can be lived between places.

Documenta14’s overarching title is Learning from Athens, one that has proved contentious in its attempts to decolonise the exhibition’s Western European framework. The perceived takeover of the Greek capital by the German exhibition, in uncomfortable resemblance to German-led EU austerity within the country, also implies a certain reciprocation from Athens. In Kassel, the Fridericianum Museum, traditionally Documenta’s centrepiece, this year plays host to the collection of the EMST, Athens’s near-bankrupt and still-unfinished museum of contemporary art. The display here is an adapted museological study of the collection, which stretches from 1960s Minimalism to the present day, including a range of works from Bill Viola and Emily Jacir to Greek contemporary artists such as Chryssa and Janine Antoni. By placing the EMST at the heart of the exhibition, the exchange raises questions about what it means to view objects out of context–what it means to have an artwork without a permanent home. It is difficult here to fully understand the background to how and why these works were acquired and selected, when the wall texts–which are sparse–do not go into detail on the Fridericianum’s history as the first public museum in Europe and, briefly before that, the seat of Germany’s parliament. There are many discussions to be had on the need for public museums, and the presence of these institutions as places for conversation and exchange. Displacing a collection begins to raise some of these, but feels problematic and little explained.

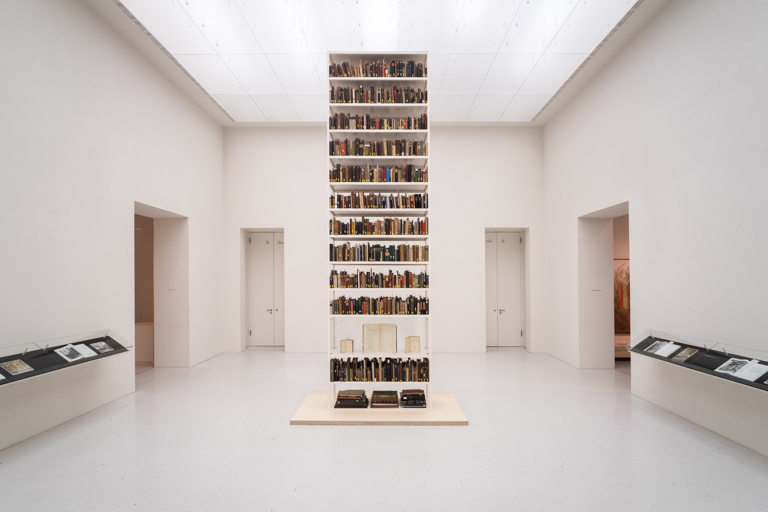

Outside, Marta Minujín’s The Parthenon of Books commands the Friedrichplatz square, a colossal sculpture-cum-library of banned books from around the world. The sheer number of copies of the Twilight series clinging to the Athenian columns is staggering in itself. Originally enacted in Buenos Aires in 1983, the work is a very literal depiction of the democracy of knowledge, which will then be broken down and the books distributed amongst people at the exhibition’s close. Again, the installation’s placement within Kassel is symbolic–the Friedrichplatz was itself the site of a Nazi book-burning during the war. Minujín’s work directly posits censorship as a form of dispossession and questions how access to knowledge can politicize both our minds and our bodies. In the Neue Galerie, another towering library by Maria Eichhorn displays books looted from Jewish collections that eventually ended up in German libraries after the Second World War. Much like Minujín’s work, books here are significant for their contents, but also for what they can come to represent as a displaced object. How can we reconcile the violent way in which a privately-owned object becomes a public object?

Seemingly private explorations of the body confront viewers in the Neue Neue Galerie, a concrete hulk of a former post office in the north of the city that foregrounds issues of labour. Maria Hassabi’s performance, staggered throughout the venue, with its main iteration upstairs against a pink carpet backdrop, returns to the core of bodily movement. Entitled STAGING, the performance ties in with many of Documenta14’s prominent tropes–industry, the body, and this idea of “scoring” or “staging” an artwork. Musical scores of archival dances and performances are dotted all around the city, displaying this visual programming of the human body. Hassabi’s performers move slowly, quietly, whiskers of movement that displace the body from where it was before. They twist into new positions that have been staged for them, in a rhythmic exploration of human motion.

There is so much on view around Kassel that sometimes these quiet artworks can get lost. It’s worth spending time with Ahlam Shibli’s photographic portraits of two groups of people who migrated to Kassel and the surrounding region; refugees from Eastern European countries after the war and Gastarbeiter, or guest workers, from Turkey and the Mediterranean who came to boost the German economy from the 1950s. Each image has accompanying text providing personal stories of xenophobia, entrepreneurship, romance, perseverance, and homesickness. In its subjects’ various responses to their new surroundings, from rejection to embracement and everywhere in between, Jonas Mekas comes to mind again. Displacement can be something physically inflicted upon a person, but also a state of mind that questions whether anyone really has a home in the first place. Documenta14 stages this unsteadiness for the viewer, splitting itself across two cities, numerous venues and multiple voices. As Mekas wrote while displaced in 1945, “Very little firm ground left under my feet. Everything’s moving… I don’t believe anymore in any final, categorical ideas. I prefer chaos, anarchy.”