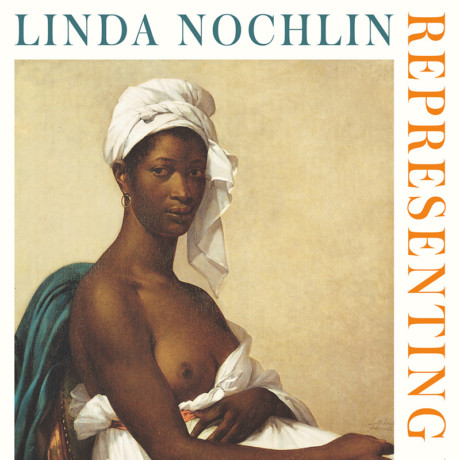

Male painters are often “sentimental, traditional and cliched” when it comes to portraits of female experiences—writes Linda Nochlin, the brilliant mind behind that much-quoted 1971 ArtNews essay (with a title that would make the clickbait generation proud)—Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? Although that essay is not included in Representing Women, the book brings together a collection of equally seminal but lesser-known writings by the American art historian—originally published two decades ago in 1999, the book has been out of print for years. Nochlin passed away in 2017, aged eighty-six.

It’s perhaps unsurprising that Thames and Hudson are reviving this title twenty years on, with a new audience and fresh market. The discussion around the female gaze, female representation and visibility is fervent, as well as the socio-economic climate shifting notions of gender and its relationship to power. Nochlin’s comeback is timely. Although the essays in Representing Women are rooted in a discussion of eighteenth and nineteenth-century painting, Nochlin’s field of expertise, it’s hardly limited in scope. Her core ideas have inspired new theoretical and practical thinking around the role of women in the arts and in society, tackling thorny issues from the use of female sexuality and nudity, portraits of motherhood by men and women artists, and the depiction of violent, angry and self-empowered women, “the most extreme exemplar of a feminine being as independent agent of her own destiny.”

Nochlin makes a clear separation between the representation of women, and women artists, and women in the world. This fundamental clarification is crucial to understanding what we now might refer to as the “female gaze,” as the artwork, the artist and their function are so often conflated and confused, with meaning subsumed by medium and vice versa.

“Why were there so few male nudes by women artists, and so many female nudes by males?”

It’s not just Nochlin’s ideas that are radical. She does away with dry academic methods and employs a direct, sometimes anecdotal and personal “bricolage”. She’s open-ended and asks a lot of questions—not shying away from giving her own opinion but also leaving space for us to think with her. It’s perhaps a force of habit, having spent decades teaching revolutionary feminist classes at Yale, CUNY and Vassar. In a wonderful memoir that serves as the introduction to Representing Women, Nochlin recalls how, in 1969, the personal and the political came together, as they often do: she had a baby, and discovered the Women’s Liberation movement in the US.

It’s particularly thrilling when Nochlin deconstructs the works of apparently “avant-garde” artists, cherished names like Courbet and his “excessively erotic” views of women. Failing to identify with Courbet’s languishing nude women or with his lascivious gaze, she illustrates with panache why it is so important to be able to locate oneself in great, celebrated works of art. It is via Courbet that she raises the fascinating and still unresolved question about the use of female nudity: “Why must transgression—social and artistic alike—always be enacted (by men) on naked bodies of women?”

In painting, that is a very significant issue. “Why were there so few male nudes by women artists, and so many female nudes by males? What did that say about power relations between the sexes, about who was permitted to look at whom? And about who was objectified for whose pleasure?” It was only in the second half of the twentieth century that images of female nudity and sexuality by male artists began to be challenged by art historians like Nochlin.

“She’s open-ended and asks a lot of questions—not shying away from giving her own opinion but also leaving space for us to think with her”

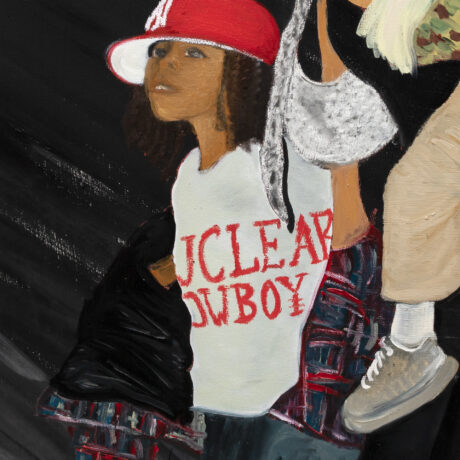

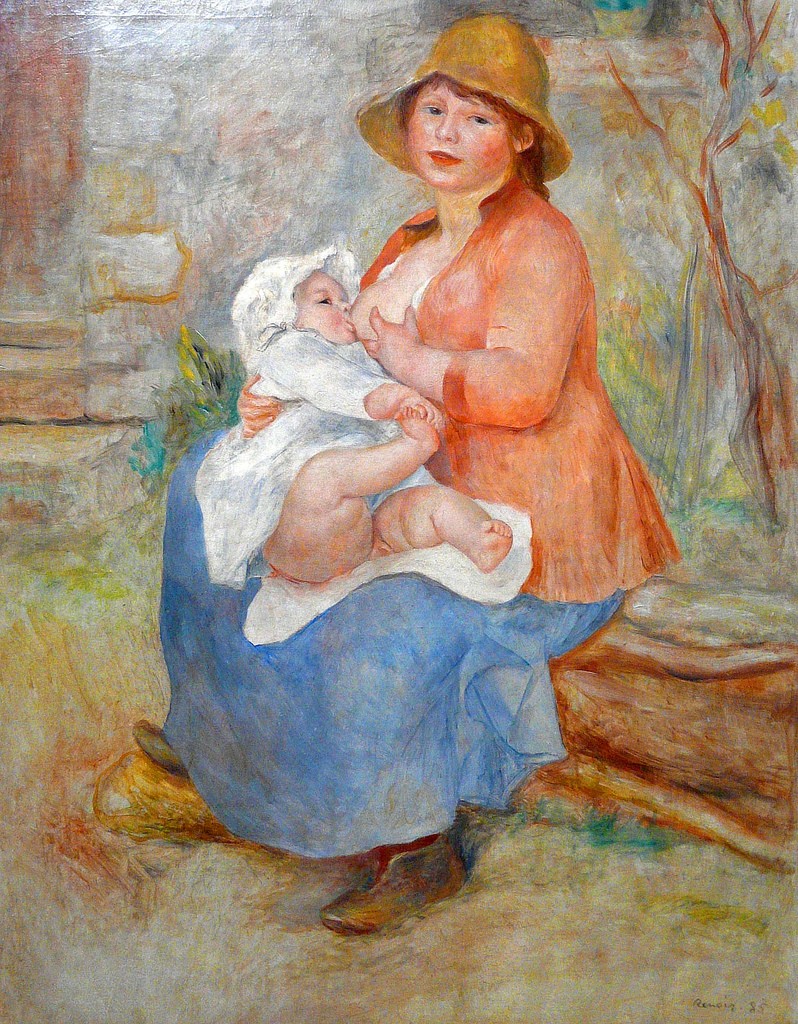

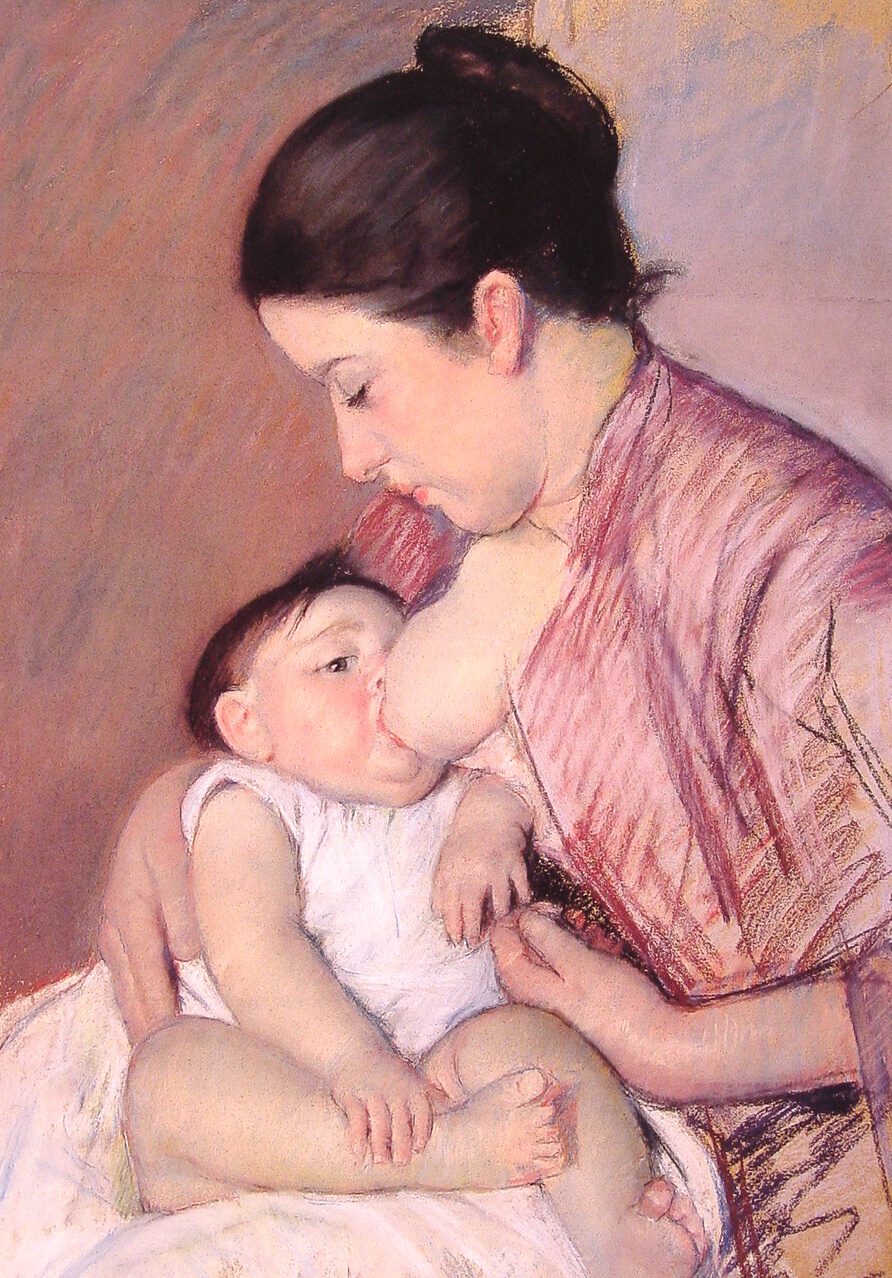

Elsewhere, Nochlin deals presciently with topics that are popular again in art—universal themes like motherhood, comparing works by Dorothea Tanning (currently on show at Tate Modern) to Renoir’s wife nursing their infant. Juxtaposition is an effective method Nochlin returns to—not without humour. Her 1972 “Buy My Bananas”—a photograph of a hirsute man holding a tray of the fruit at penis level, is reproduced side by side with the nineteenth-century photograph, Buy My Apples, of a woman naked (save for a pair of knee-high socks) holding a tray of apples at chest height. As Nochlin deftly demonstrates, it is often up to the women artists to break with tradition.

But would Nochlin have supported the idea of a “female gaze”? Probably not; as she makes clear when she writes about Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro’s Womanhouse (1972), she does not believe in a feminine style. But that’s not to say she doesn’t agree with “supporting the work of and the working lives of contemporary women artists.”