It’s easy to see the transactional mechanics of more traditional disciplines like painting, sculpture, photography, and even video; but more difficult to comprehend the buying and selling of pieces that are based on viewers’ presence, and as such, ephemerality. Another matter inherently problematic to the selling of such work is, as Zabludowicz Collection programme director Maitreyi Maheshwari, told ArtNet in 2017, many such artists are “keen to reject the forms of market-led commodification of artworks, which is still very much focused on material objects”.

Isabella Maidment, curator of contemporary British art at Tate, spoke to us about how the gallery’s acquisitions of performance art transform the role of the curator—traditionally “keepers of objects,” she says, “but [with performance art] you become more of a producer. It’s amazing how it’s shifted over the last ten years or so.” Tate’s senior curator of performance Catherine Wood told Artnews that the institution’s acquisition of performance pieces exemplified a shift in emphasis away from “valuing material objects towards thinking about how a work can be encountered through time, or how a document of a past action can simply fire the imagination.”

The one artist who’s probably had the most impact when it comes to the buying and selling of performance art is Marina Abramovic, who had no small part to play in capitulating the medium from fringe oddity to mainstream darling. It’s Abramovic, too, who seems to be the most “collectible” of such artists—little surprise, perhaps when you consider that her blockbuster 2010 MoMa show The Artist is Present, which spanned 250 hours, attracted 850,000 visitors, no shortage of celeb love and was even spun out into a feature-length film documenting the project.

“The most obvious solution to the buying and selling of performance is through documentation”

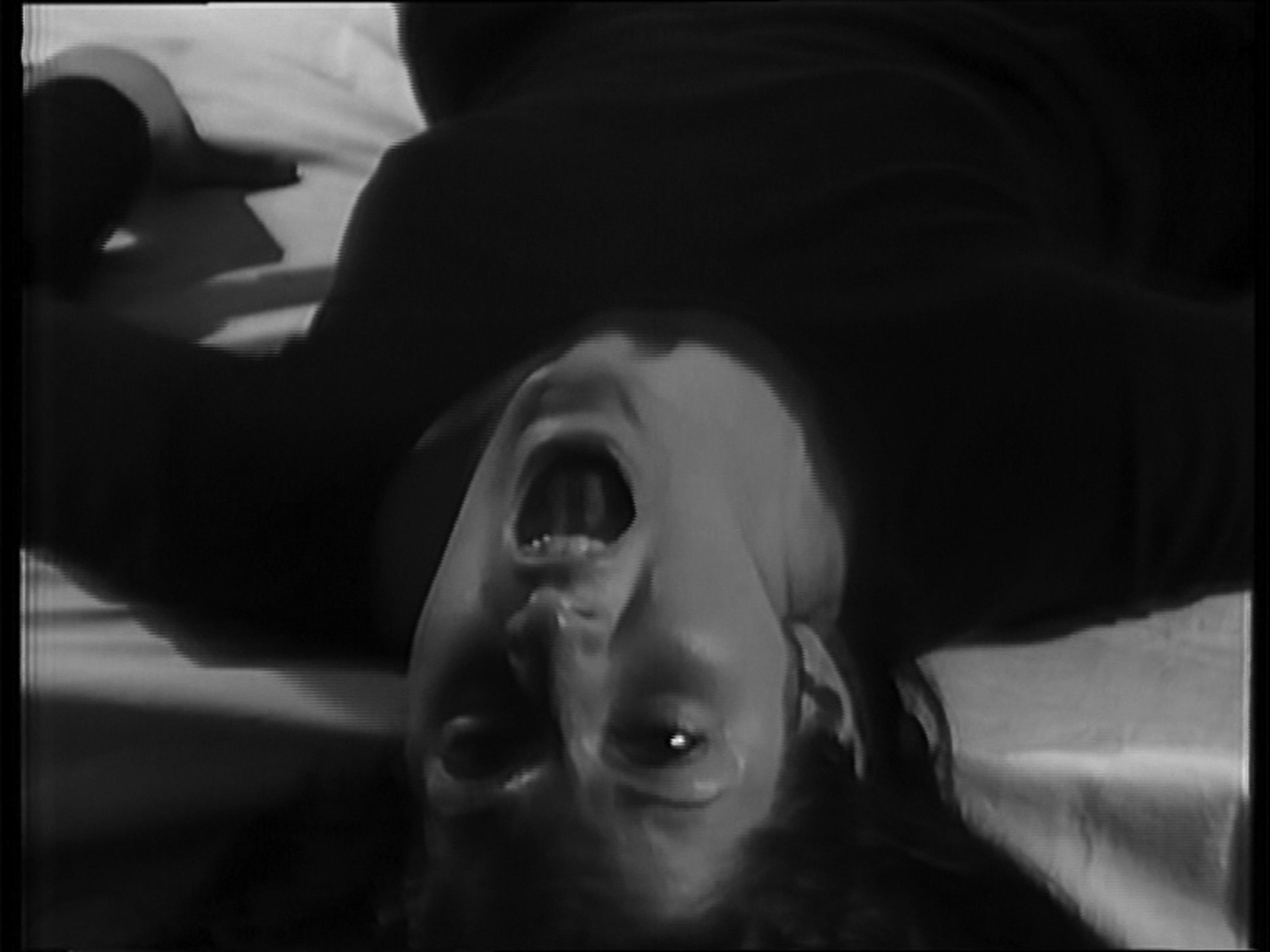

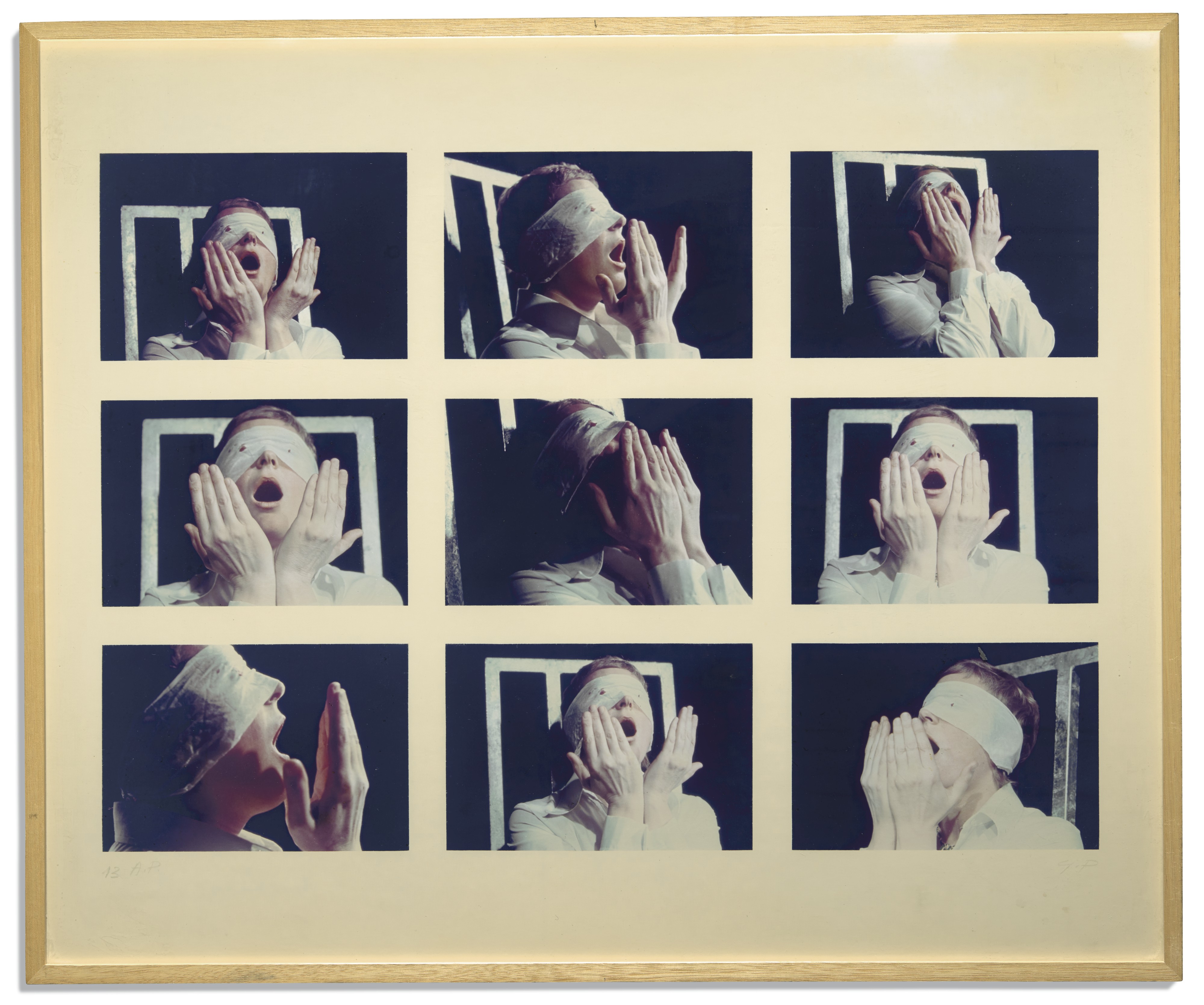

But how, aside from these vast commissions, do artists actually make money from performance? The most obvious solution to the buying and selling of performance is through documentation, such as photographs of events or video pieces, or even props that were used—though this would seem to be relevant, perhaps, to only the more established artists, with decades of art-making already behind them.

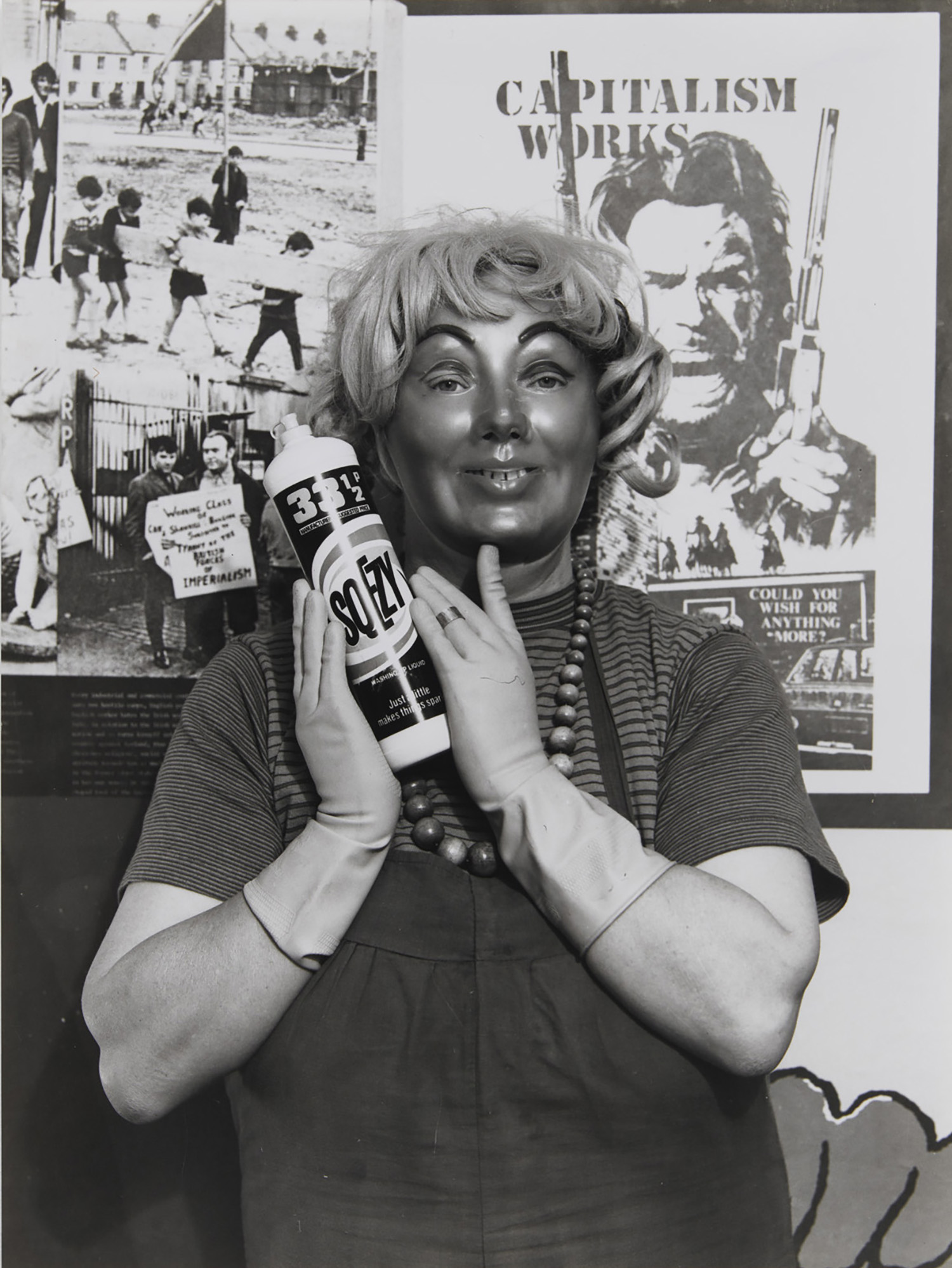

And even if an artist does sell such documentation, it can be argued that such pieces are in no way a reflection of the action itself. According to Richard Saltoun, founder of his eponymous London gallery which specializes in conceptual, feminist and performance artists, “it depends from case to case” on how well you can get a sense of the artwork, without having actually seen it as it were intended.

“The documentation is, on the one hand, an entry-point to a performance or action, but it’s also a standalone body of material that can be enjoyed and appreciated on its own—it’s not acting as a kind of poor substitute for something that’s no longer there. Some documentation and archival things are as interesting as the performances themselves; but not because they stand in for it, but they offer a different understanding of an artist’s working methods.”

© The Estate of the Artist; Courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery

That hasn’t stopped the sale of performance art has in recent years proving to be enormously profitable. The David Lewis Gallery in New York, for instance, has sold many performative installations and individual works by multimedia artist Dawn Kasper to both public and private collections; through fairs including Frieze New York, Art Basel Miami, LISTE Art Basel, and Artissima.

“Some documentation is as interesting as the performances themselves because they offer a different understanding of an artist’s working methods”

As for what sells best when it comes to physical pieces relating to performance art, Saltoun says that it’s obviously the pieces by the most famous artists; but also works that are “independent from the action or performance, that could look just as good as a photography fifty years later as the original performance fifty years ago. In these instances, they’re well choreographed and photographed—that great moment where those things work together to represent the action and work with an autonomous life.” He adds, “There’s an increasing interest in women artists, who were very important in the development of performance art.”

Tino Sehgal, however, is famously outspoken in his refusal to allow documentation of his work. His work is sold by giving permission for his “situations”, as he terms his pieces, to be repeated through a set of rules that he provides. For all his strictness and control—his rigid focus on his art as encountered that can only be experienced in the present—Sehgal has carved a comfortable and rather traditional little corner for himself in the art world: he’s represented by Marian Goodman Gallery, and MoMA bought his work Kiss for $70,000 in 2008.

Quite what they have acquired is tricky to comprehend: Kiss is, of course, a “situation”—but one that sees a heterosexual couple on the floor, kissing and embracing, moving together with slow choreographed motions. They’re trained dancers, rather than just amorous chancers; but nonetheless, their motions were designed to be a one-off: ephemeral. Perhaps, as the cynics among us would say, it is just like first flushes of true romance.

So how can you buy it, let alone display it after the event? As Artsy explains it, Sehgal sells his work by “transmitting the work’s blueprint to his gallery representative. The purchasing collector or institution is then given those instructions verbally. And they may only re-stage the work with the aid of Sehgal himself or with one of his team members’ guidance. If Sehgal quits the art world or when he passes away, the legal right to stage his performances will vanish with him.”

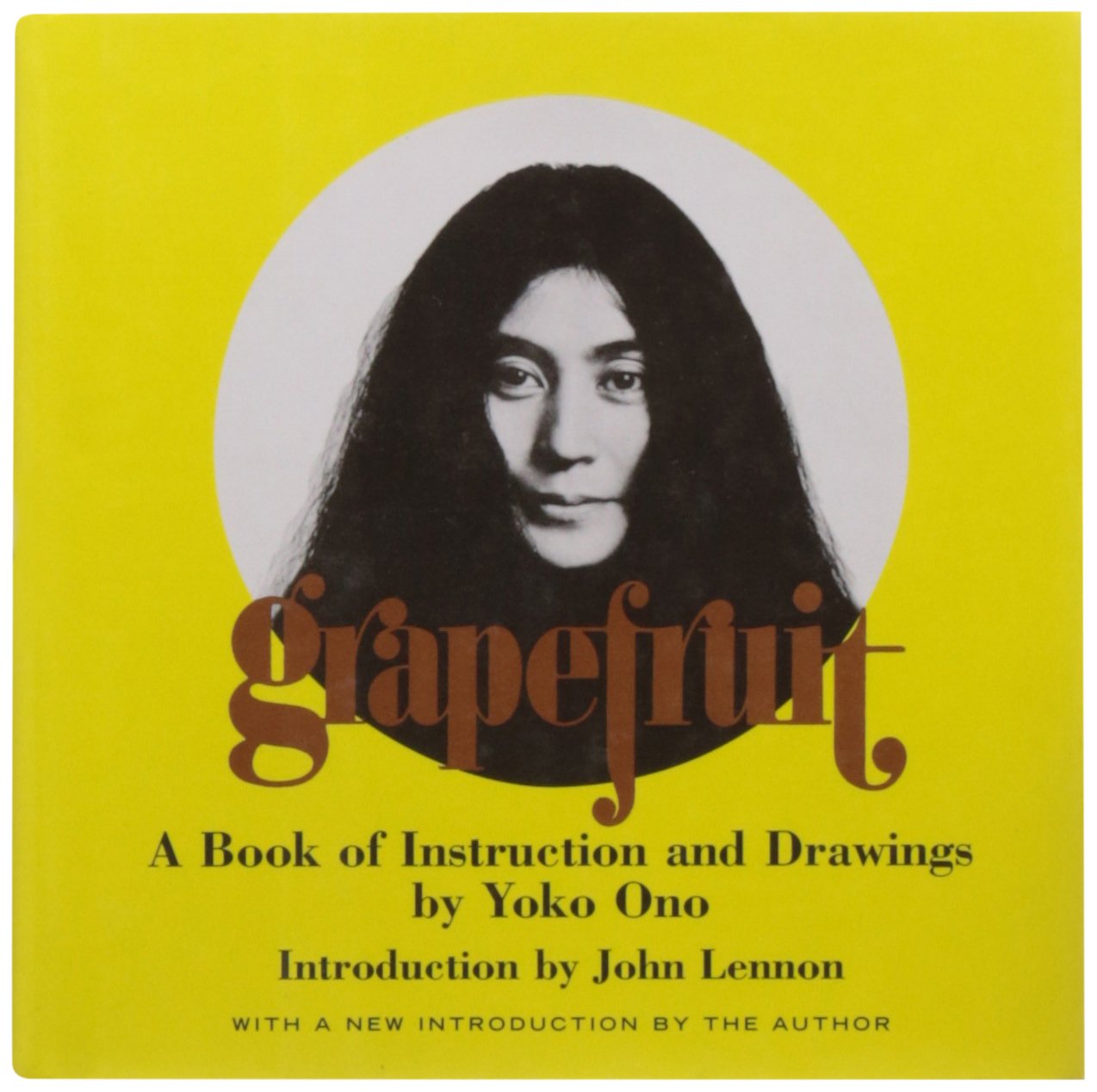

Other artists who are best known for their work in the performance sphere have made pieces that are far more physical in their realization as sellable objects, or at least movements that can be housed or shown again, or indeed, bought; such as in photographic editions or books—like Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit.

Theaster Gates, meanwhile, made the money to fund his 2015 Stony Island Arts Bank project—which saw the artist convert a derelict bank in Chicago into a cultural space composing visual art galleries, events and a library for books and vinyl records—in a rather innovative way. Though the property was purchased for just $1 (around 82p, in UK currency); the renovation was funded through 100 brick-like blocks, created from salvaged marble elements of the building and inscribed with the words ‘In ART We Trust’, which he dubbed “bank bonds”. These were sold at Art Basel in 2013 for $5,000 each.

Marina Abramović cashed in on her 2005 work Seven Easy Pieces, which was staged again at the Guggenheim and involved seven reenactments of other performance pieces—two of her own and five by other artists such as Gina Pane, Joseph Beuys and Valie Export—performed on seven consecutive nights (for which, of course, the artist was paid). She’s certainly savvy when it comes to monetizing her work: the artist’s longtime dealer Sean Kelly has said that photographic prints documenting her work sell for anywhere from $25,000 to $500,000. In 2014, Abramović was paid $150,000 to work with Adidas on a World Cup ad, and told Bloomberg she spent $50,000 making the film.

Of course, not many performance artists can claim to be as much of a “brand”—and as such, as highly paid—as Abramović. Many artists rely on a vast number of other performers to realise their pieces; who are often unpaid, or paid poorly. In 2015, artists Brennan Gerard and Ryan Kelly partnered with the Guggenheim Museum in New York on the piece Timelining, part of Storylines: Contemporary Art at the Guggenheim, which aimed to promote labour standards for themselves and the other performers.

“Not many performance artists can claim to be as much of a “brand”—and, as such, as highly paid—as Abramović”

The piece saw ten “couples” (not just romantic partners but pairs of siblings, other relations and a mentor/mentee) recite stories about their shared histories in the space’s rotunda floor. Gerard and Kelly created a large document setting out how the performers would be paid, and ensuring that it had a life after the event itself. The piece was acquired by the Guggenheim; part of a number of performance art pieces it has purchased.

Speaking to the New York Times, the artists said that they saw performer compensation “as a blind spot in how performance was entering collections,” since “the labour of the work is inextricable from its aesthetic content.” Gerard and Kelly had learned that in 2010, museums were paying performers an average of about $20 [around £16] an hour—which they viewed as far too low a figure. That rate applied to several major 2010 shows including Marina Abramović’s piece at the Museum of Modern Art and Tino Sehgal’s at the Guggenheim. The establishment agreed to pay performers in Timelining a better rate than the then-New York living wage of $13.13 [around £10.50] an hour, and take into account the necessary preparation before the performance.

The issue around money and performance art isn’t just tied to how to sell or buy it but that, in so many cases, performers involved in pieces are often either compensated poorly or not at all. The notion of poorly paid, or unpaid labour in the art world is hardly unique to performance art: for years debates around assisting, interning and so on have rolled on with apparently little resolution. So, the answer to how to really monetize performance art? Get really, really famous.