It’s a fact that the Courtauld has reopened to the public following a three-year, £57m makeover, but I can’t help thinking about fiction. The protagonist of my forthcoming novel, Wet Paint, has been visiting the gallery once a week for the past four years. It’s a ritual, a routine that keeps her going.

She knows exactly where to go. She skips the prints and drawings on the first floor and, having climbed up another set of stairs, glides through the first five rooms straight to room six. She has a thing for Manet’s barmaid, you see, finds her mind catching on those heavy eyes, that jagged fringe. If she were to visit now, though, things would look a little different.

The renovation works, which began in 2018, are the most significant in the Courtauld’s history. That history began in 1932 when, together with Viscount Lee of Fareham and Sir Robert Witt, Samuel Courtauld co-founded the Courtauld Institute of Art in Portman Square, Marylebone, an independent college of the University of London offering courses in art history, curation and conservation.

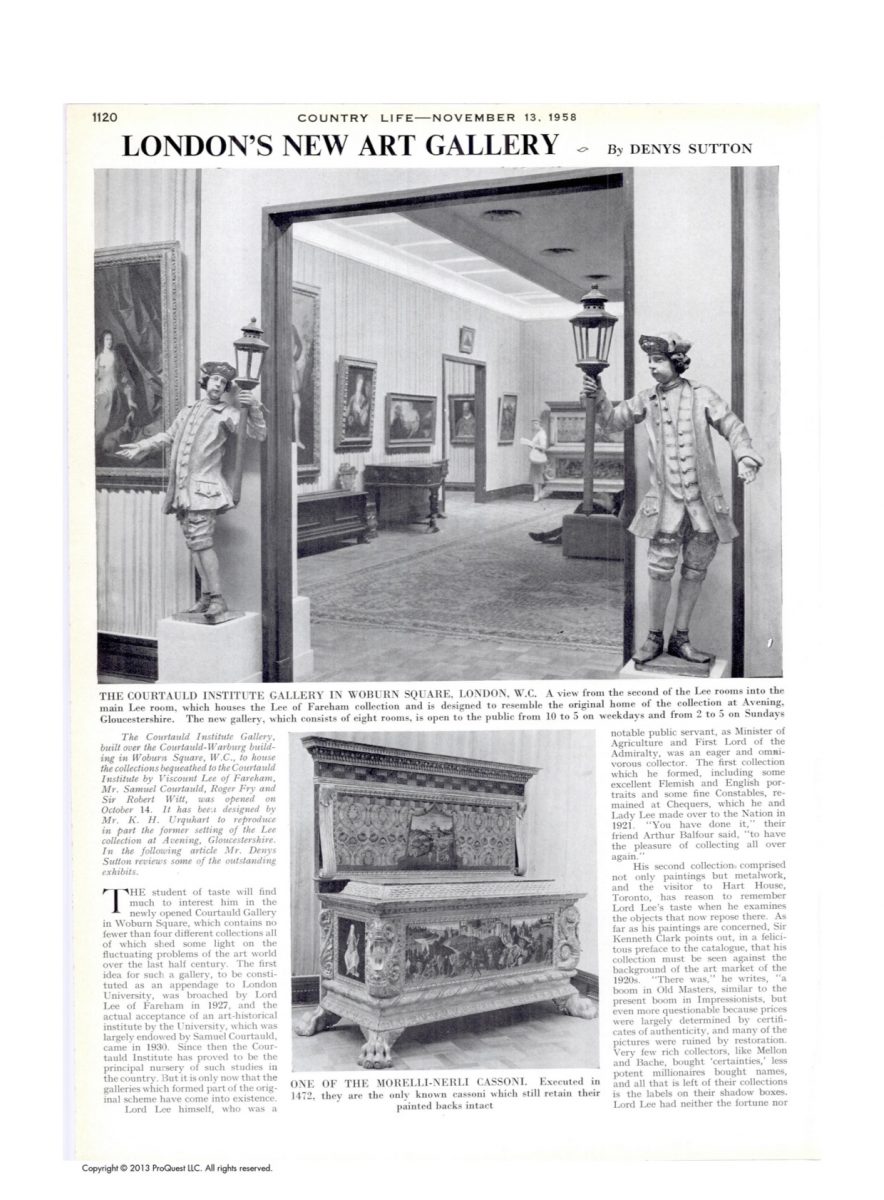

Comprising the collections of the three co-founders, the Courtauld Gallery itself was established in 1958. Roughly thirty years later, both institute and gallery packed up and moved to Somerset House, the neoclassical complex between the Strand and the Thames.

The aim of the modernisation project, says Deborah Swallow, Märit Rausing director of both the institute and the gallery, is “to make the building work seamlessly as one.” It’s unusual, and very fortunate, for a university to have its own collection, and vice versa. The plan, called Courtauld Connects, is to make more of that, to shore up the relationship between teaching, research and the artworks, and to make all three more accessible to the public.

“The renovation works, which began in 2018, are the most significant in the Courtauld’s history”

“Today, it’s about more than having a jewel-like collection in a jewel-like place,” says Stephen Witherford, director of London-based architecture practice Witherford Watson Mann. “It’s about the greater purpose, and that’s how you’re using your research skills, collection, curatorial programme, conservation and technical insight.”

Witherford and his team gained a good sense of what the Courtauld could be after they worked on the new prints and drawings gallery, which opened in 2015. “As we were nearing the end of that project, there was a competition to look at the whole building, which is what we ended up doing,” he says when I meet him at the site. “It came out of that seed.”

The studio’s proposal to open up the Grade I-listed building designed by Sir William Chambers in the 1770s chimed with the board, and together with Nissen Richards Studio, they got to work on reimagining the Courtauld’s visitor experience.

The game of spot the difference begins before you even enter the building. A series of subtle interventions have increased step-free access throughout, starting with the gentle ramping of the historic flagstones in the entrance off the Strand. Cross the threshold and your eyes will snag (in a good way) on the zingy metalwork of the spiral staircase, which has been given a lift with a fresh coat of Prussian blue.

There have been big structural changes (extending the galleries across the top floor and tunnelling through the brick vaults in the basement) and smaller modifications such as installing new environmental controls, widening doors and losing clunky picture chains.

“The core is very true to the Courtauld ethos: showing works in a way that allows people to take their time and look carefully”

The restoration of the building has provided an opportunity to rethink the curation, with masterpieces from the collection (ranging from the Middle Ages to the 20th century) thoughtfully redisplayed. “The core is very true to the Courtauld ethos, which is about showing works in a way that allows people to take their time and look carefully,” says Swallow, as we sit on a bench in front of Gainsborough’s intimate portrait of his wife, Margaret. “You’ll see, we’re not overloaded. The aim isn’t to show everything.”

The result is a gallery experience that gives both art and viewer room to breathe. Portrait of Margaret Gainsborough (c. 1778), for instance, hangs on a lilac wall panel in its very own niche. Free from fusty furniture, the gallery’s starry collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist canvases shines even brighter in the newly restored Great Room, the oldest purpose-built exhibition space in London.

“Today, it’s about more than having a jewel-like collection in a jewel-like place”

Two new galleries on the top floor provide space for temporary exhibitions. Specially commissioned for the curved wall above the spiral staircase, British painter Cecily Brown’s Unmoored from her reflection (2021) riffs on Manet’s Study for Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (The Luncheon on the Grass) (c. 1863). While Manet foregrounds a classic female nude, Brown’s expressive dreamscape focuses on two naked men. Elsewhere, a pleasurable jolt comes in the form of a small, cosy room with peachy walls devoted to the Bloomsbury Group.

“The collection is zipped-up tight together,” says American artist and Courtauld alumna Jann Haworth. “It makes for an experience that’s human-sized. You can grasp it.” It’s the human side of the institute that Haworth appreciates, too. In 1961 she arrived in London fresh from California with zero understanding of the British university applications system. “I just turned up at the Courtauld and said, ‘I’d like to go here.’”

“It was January, so it didn’t make any sense,” she continues, “but the person I spoke to was very accommodating and told me I could be a certificate student. I selected some courses, which were probably more than I could handle given that I went on to be a full-time student at the Slade shortly after. Still, the Courtauld was the first institution that took me in.”

“The collection is zipped-up tight together. It makes for an experience that’s human-sized. You can grasp it”

Though students and staff are yet to return to Somerset House from their temporary lodgings near King’s Cross, the institute and the gallery are gradually coming together. Physically the building is now a complete circuit, with the East and West staircases connected via the newly open spaces above and below. A new object study room invites students to work closely with the collection, while a learning centre welcomes school and community groups.

The work of the conservation department is highlighted in the Blavatnik Fine Rooms, which span the second floor and provide a light-filled backdrop to works from the Renaissance to the 18th century: following three years of structural restoration and surface cleaning, Sandro Botticelli’s luminous altarpiece The Trinity with Saints Mary Magdalen and John the Baptist (c. 1491-94) takes centre stage.

- The Courtauld Gallery. Photo: Alastair Fyfe

- The Bloomsbury Room at The Courtauld Gallery. Photo © Jim Winslet

The reopening has been a long time coming: there were of course delays due to the pandemic, and a medieval cesspit was discovered in the basement, which ironically sits below some new loos. The work isn’t over, but for now, what a pleasure it is to welcome home Cézanne’s cardplayers, Degas’s woman at the window and, of course, Manet’s barmaid.

You see them in a different light (literally) and in different positions against different coloured walls. Walking around, I notice things about the art that I hadn’t noticed before, and the same goes for the architecture, which, like the works, shines brighter. By the time I’m done, I’m itching to go back to the beginning and do it all again, which is the brilliant thing about this place.

“It shouldn’t just be checked off,” says Haworth, “It’s an again and again experience. It really is a companion.”

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, will be published by Trapeze in April 2022