In recent years, the landscape of filmmaking has transformed. While user-created content has been a mainstay for almost a decade with social media platforms such as Instagram, the recent rapid ascent of TikTok represents an irreversible closure of the gulf between creator and consumer when it comes to moving image. Whether it’s a Fleetwood Mac fan drinking cranberry juice or a twerking duck, it seems that everyone can have their 15 minutes of fame.

More often than not, that ‘fame’ is as much down to a smart video edit as it is the personality of the people in front of the lens or the nature of the content itself. Most people in the 21st century are consciously or unconsciously literate in the language of film in ways that would have been unimaginable for previous generations. It is no longer a craft shrouded both in mystery and prohibitively expensive equipment: the ever-increasing accessibility of editing software means that many of the tools that were once exclusive are now at the fingertips of non-professional video-makers. The latest global phenomenon that could permanently alter the nature of moving image art is, of course, the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Many will be viewing a film on the same screen that they use for work emails, television, social media and news”

Few would argue that the experience of viewing more traditional media, such as sculpture and painting, can accurately be replicated digitally. However, it is easier to make the case for video art that seamlessly transitions from gallery screen to laptop, or even phone. But for artists, curators and viewers, the reality of that switch is less than straightforward.

For the 2020 edition of annual London festival Art Night, staged in various venues across the British capital for one night only, the team instead commissioned a series of short online pieces termed “trailers”. The ten artists in the postponed festival programme were asked to respond to the question, “What do you feel like showing right now?” The richly varied resulting works included videos uploaded to YouTube (Mark Leckey, Alberta Whittle and Guerrilla Girls), sound pieces on Soundcloud (Philomène Pirecki, Imran Perretta and Paul Purgas), downloadable PDFs (OOMK) and posters (Sonya Dyer).

Although artists had just two months to work on the pieces, the video works—notably those by Leckey and Whittle—stand out as pieces that feel just as moving, strange and brilliant as if they were being shown physically. They don’t feel like a consolation prize or a flimsy facsimile of an onsite artwork. Their success is partly down to the usability and accessibility of the pieces: the familiarity of the YouTube interface slashes any barriers to entry that more custom formats, often with heavy bandwidth requirements, might have.

Another reason that these films resonate is their brevity.

“There was a proliferation of digital projects that seemed to come out very quickly,” says artistic director of Art Night Helen Nisbet, reflecting on the first lockdown in the UK. “I certainly felt like I wasn’t ready or able to look at them. For a long time, I just wasn’t engaging at all.” The Art Night team soon realised that the commissioned artists already had “so many ideas, and a feeling that was very much of the moment,” she says. “By asking the artists, ‘What do you feel like showing?’ the onus wasn’t on them to make anything that aligned with the traditional idea of what a digital online work might look like. It was just what they feel like showing, given the context and what’s going on in the world. It’s more like a flavour of the artists’ mindsets at that moment in time.”

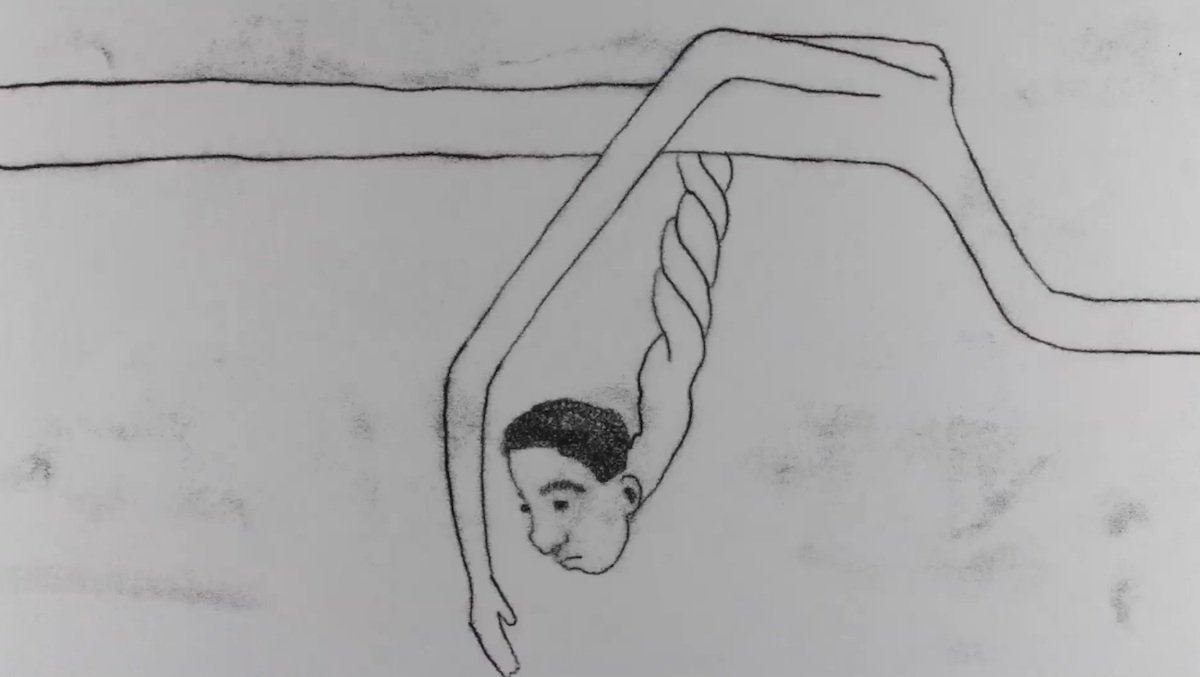

- Isabel Barfod, Hear Me Out (stills), 2020. Courtesy the artist and Artists Moving Image Festival, LUX Scotland

- Sharon Hayes, Fingernails on a blackboard, 2014, still. Shown as part of Give Birth to Me Tomorrow, from Artists Moving Image Festival, LUX Scotland

Timing is of the essence when it comes to programming artists’ films online. When adapting the usually Glasgow-based Artists Moving Image Festival (AMIF), Kitty Anderson, LUX Scotland’s director, decided to run the films online throughout the year (from January to November, programmed around the lunar calendar), rather than showing everything in just a few days. “We’re more interested in making things meaningful than just making them available,” she says. “First of all it’s about getting them online, but then it’s creating an opportunity for discussion, and with that, building the community and other kinds of relationships (which of course are currently online) to investigate the work and pull threads together through everything we’re doing.”

These adaptations take into consideration the limited attention span of digital audiences. Many will be viewing a film on the same screen that they use for work emails, television, social media and news. It takes a cognitive shift to engage with it as a gallery or cinema site too. Art films demand the full attention of the viewer—something that most people are not accustomed to bestowing on a single object, let alone one as multifunctional as a phone screen. This fact was made plain in artist and writer Alexander Storey-Gordon’s review of Alchemy Film Festival last May, in which he described watching films while on the toilet: “I am a consumer on my sad throne choosing when and where I give my attention, and the festival is simply one of many competing media.”

“We’re more interested in making things meaningful than just making them available”

The immersion of artist films among the other vast swathes of online content is not ideal, especially when compared with the focus of a darkened gallery screening room. “Since we were not able to go and see exhibitions and generally artworks in person, moving image pieces seem to sort of fill up the content gap of different art institutions and art initiatives in their online digital programmes,” says Milan-based artist Natália Trejbalová. “I’m glad that this medium and practice has got more attention, but the problem is that we watch these pieces in the same virtual space, laptop, and advertised through social media platforms, where we absorb an enormous quantity of moving image content (YouTube, Instagram and TikTok). That’s not a neutral environment. How can you concentrate if the rules of attention are completely different in this environment?”

Of course, one of the main advantages to online events is accessibility, both physical and in terms of global reach. AMIF screenings at Glasgow’s Tramway space can usually cater for around 150 viewers. Online, they attracted around 800 from as far afield as Mexico, Canada and New Zealand.

According to Greta Hewison, production coordinator at Film London’s Artists’ Moving Image Network (FLAMIN), the Jarman Awards found a similar positive response when its 2020 award-winning films were screened online. However, the limitations of viewing on a laptop at home make it “a very different experience,” she concedes. “Artists working with the moving image think about all aspects of their work in great detail, right down to the quality of the soundtrack. It’s probably going to sound very different on a laptop than it is in a physical screening space where they have a sound system, and they’ve got technicians that are trained to think about the best, most optimised way of displaying work.”

Another consideration is digital inequality: not everyone has access to a computer or smartphone, and those without are “more likely to to engage with artists’ moving image better at a free screening event in their local art centre,” says Hewison. “I think people are going to be considering more of a hybrid way of presenting work in the future.”

“Now that people are used to so much moving image content on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok, it’s not a neutral environment”

The exhibition of art in people’s homes inevitably means ceding control of how it is shown. Everything from the volume to the screen size and image resolution to the level of distractions around the viewer is totally out of artists’ and curators’ hands. Anderson suggests that screening organisers should make it clear what is being asked of their audience (prominently displayed runtimes, for instance) “so that they are able to reduce those distractions as much as possible.” While newer platforms like Twitch might seem tempting, there is a general agreement in the industry that the viewing experience is both easier and smoother when using familiar, easily-navigable hosting platforms such as Vimeo.

Online and onsite film experiences also offer different opportunities for connection for both artists and viewers. While online platforms mean that people can potentially interact with others from across the world, there remains an argument that such connections can’t possibly replicate those of real-life encounters. Nisbet says that she feels anxious about the possibility of losing the “kind of intense contemporary art experiences in municipal spaces like high streets, libraries and working men’s clubs, or what it might mean to lose that feeling of bodies in space. Some artists and some works really need that, and we’ll never be able to replicate that through a screen.”

Some artists argue that a good piece of art will work just as well on a phone screen as it would when shown in a cinema or gallery. “Coming from media arts, you always say, ‘Does this fit a festival? Will I be okay with it shown on just a big screen?’ I almost don’t see any difference watching it just on a phone screen as in a festival where you can’t be present,” says Belgium-based artist Aay Liparoto. “People use phones as a legitimate screen, it’s just a different size. If a piece is powerful, then the screen doesn’t really matter. What you’re saying and the story you’re telling can still be totally transfixing on a phone.”

However, if a piece is conceived as a multi-screen work, or utilises sound design in a spatial manner then it won’t create that same impact at home. While artists are now having to consider these limitations during the making of their work, another huge shift in process has been the restrictions around movement and crowds that the pandemic has engendered.

For Trejbalová

, such restrictions have meant that she’s adapted her work in practical terms, but she is resolute that the pandemic hasn’t changed her approach conceptually: “I still prefer to think about the piece in terms of the best possible conditions it can have. For me, the piece exists in the projection. I fought to make it something you can see online, but that’s almost more like the documentation of an exhibition, similar to if it was photographed, rather than being the piece I intended.”

“People use phones as a legitimate screen, it’s just a different size. If a piece is powerful, then the screen doesn’t really matter”

She adds: “One of the biggest differences between an art film based in an art space and one based at home is the projectors. I like to consider the actual projection as a sculptural object. You can’t do that when you present a video online.” This, coupled with the lack of control over how works are presented, is “very frustrating”, she says, not least because viewers aren’t engaged in a “conscious act of concentration” as they would be in more formalised arts settings. “I don’t know if the diffusion of the medium is a good thing, there’s a possibility that all the moving image production just levels down to meet the criteria of other content we meet in the same virtual space,” she reflects.

For Liparoto, however, their work has always taken into account what they term “versioning,” long before Covid-19. “I don’t normally necessarily have a 100 per cent fixed idea of how a work has to be shown,” they say. “As an artist, I believe in versioning every work: there’s not just one way or space for showing it.”

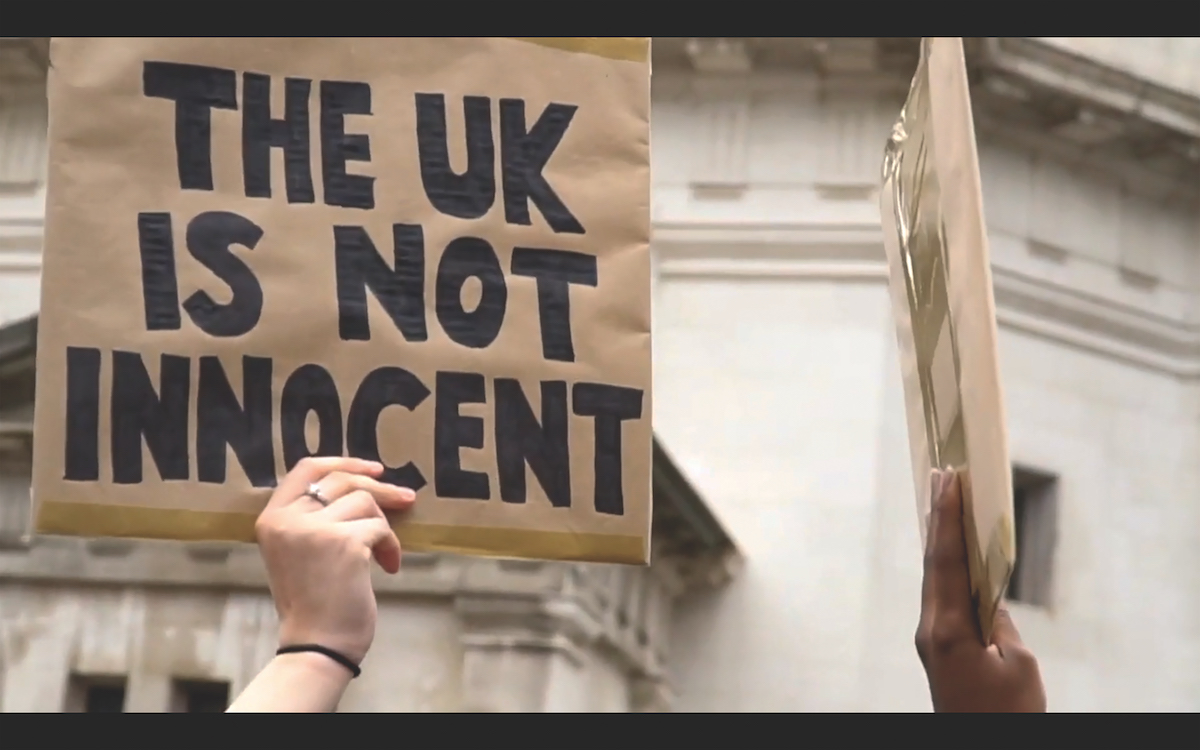

- Both: Alberta Whittle, Holding the Line (stills, as seen in Art Night's trailers), 2020. Courtesy the artist

With more than a year of the pandemic now behind us, the phrase “new normal” is thankfully less common. However, it remains relevant when applied to the showing, curating and funding of future moving-image works. All those interviewed for this piece agree that artist screenings are unlikely to return to what they were pre-Covid. The term “hybrid programming” is often mentioned in discussions around the future of artists’ film.

“If we’re not scarred by this and re-addressing the way we work, then there’s something wrong,” Nisbet says firmly. “This has brought so many opportunities and learnings in terms of how we can properly make things accessible, especially to people outside of major cities and towns. I have no doubt that most projects will now be considered with a much longer lead time. It’s very hard to imagine what an emergency situation might look like until you’re in one.”