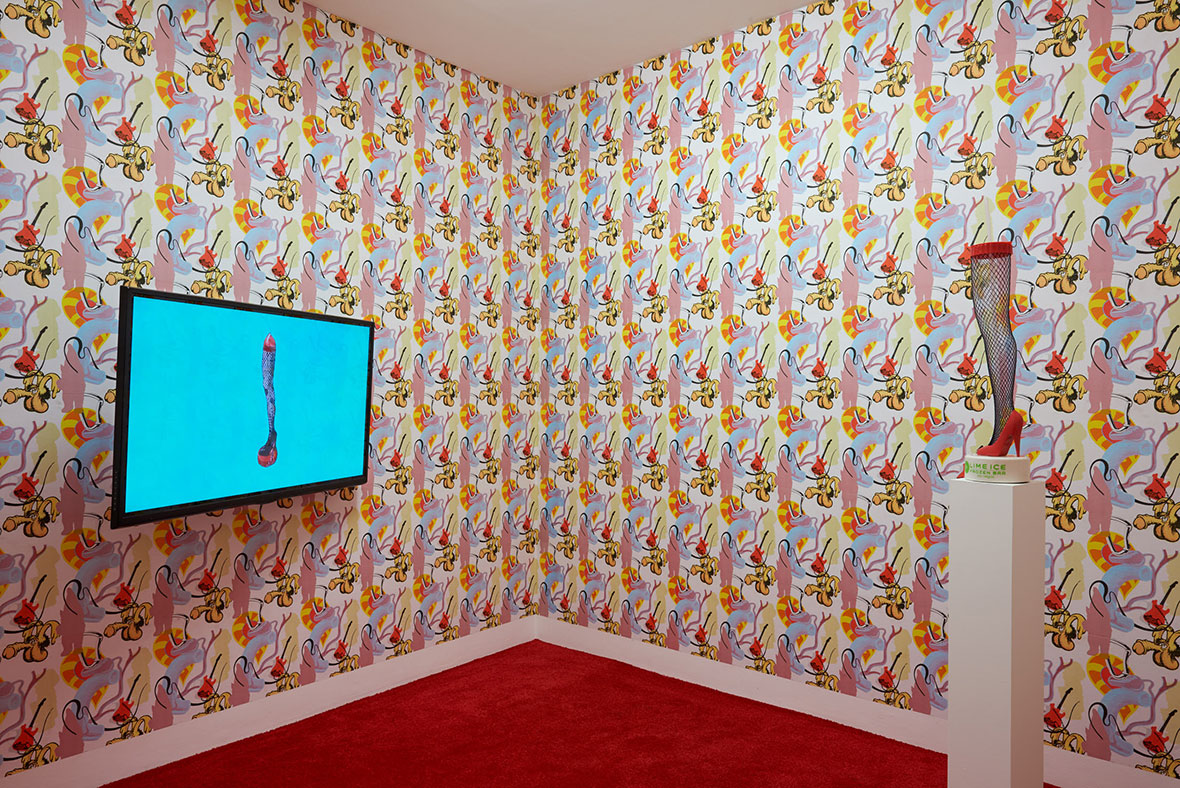

The Horse Hospital, London’s longest running, truly independent arts space, states clearly that it rejects “professionalism, strategy, power, selling out and the market”. Its refusal to bow to capitalist-led, homogenized culture is undoubtedly why it remains so celebrated. Founded in 1993, its diverse programme of visual arts, film, fashion, literature and music—with common themes ranging from LGBTQ+ artworks to witchcraft, horror and psychedelics—it’s hard to imagine this breadth of work being showcased anywhere else. With its range of shows from established and emerging artists alike, there is nowhere else quite like it—especially not in central London.

Last year the space announced that it was under threat of closure, with a 440 per cent rent rise by its private landlords Evannance Investments. This isn’t the first time the space has faced such threats: in 2001 and 2014, the building was saved from redevelopment only thanks to it being granted listed building status as a centre of cultural significance. But now, unless the space can negotiate a fair rent by the end of March, it will likely have to take the case to court and incur legal fees of up to £40,000. Or, more likely, it will have to close.

As an artist-run non-profit, the venue’s income is generated through its Contemporary Wardrobe Collection, established in 1978 by costume designer and Horse Hospital artistic director Roger Burton, which has over 20,000 items that are lent for use in film, TV, fashion shoots and museums. Previous wearers have included David Bowie, The Beatles and Kanye West; brands including Burberry, Gucci and YSL have used it as a research resource. Other income is generated from the rental of its space for events, and the sales of artworks, posters, films and publications donated by artists and other arts organisations. These revenue streams won’t be able to support the proposed new rent, and its future hangs in the balance.

The Horse Hospital’s battle feels like a significant bellwether for the state of the arts in the capital at large, as artists and art spaces alike struggle to keep afloat in a climate of rocketing rents and Brexit fallout. Post-2008-recession, landlord greed has run rampant and the Conservative government continues to demonstrate an apparent disregard for creativity—as evidenced in its curriculum changes and arts funding cuts. London’s gentrification is pushing artists out; Hackney Wick, for instance, once the warehouse-laden home to more artists than anywhere else in Europe, is now a sea of brunch spots and developer-commissioned “creative” hoardings for new-build apartments, both of which ape the area’s former artistic identity at five times the rent price.

“Property speculation and private development, aided by willing governments and councils, have forced the closure of these spaces for decades”

In their video work London and Landlords: An Unfinished Video History (2020), William Fowler and Matthew Harle point out that this isn’t a new problem: “Property speculation and private development, aided by willing governments and councils, have fragmented London’s communities and forced the closure of spaces like the Horse Hospital for decades.”

Jupiter Woods, an independent arts project space in South Bermondsey, has experienced these challenges first-hand. Founded in 2014 by six Goldsmith MA curatorial students, the group met by chance at an exhibition opening. They were offered a former house that had been converted into studios then left vacant and dilapidated—all for a total of just £600 per month in rent. While they received no arts funding for the gallery, the rent was made possible through some of the team taking up residence in the building, where the boundaries between life and work were blurred. They enlisted the help of friends and volunteers to redevelop it into a functioning space for exhibitions and residencies, with a show space, garden and three bedrooms.

Founding member Carolina Ongaro was keen to use the space to explore the idea of hospitality, asking how art and art economies can “function outside of the mainstream institutional structures of the art world”. It is an ideal exemplified by the live-in curators, who also rent rooms to friends in order to make the space financially sustainable. Over the years it has also been funded by small-scale grants and donations, although most of the work remains volunteer-based. Arts Council project grants serve to realise individual art projects, but those running the space long-term must survive through other means.

After her MA, Ongaro, who is now the only remaining founding member, worked at Thomas Dane gallery before quitting to run the space full time, briefly moving into one of the bedrooms. She now works with a skeleton team of associate director Katie Simpson and Katrina Black, who programmed literary, research and film screening events since 2018. With the surrounding area being rapidly redeveloped, times are uncertain for the space, which is currently closed until the summer.

In August 2018, London Mayor Sadiq Khan called on developers and boroughs to support the capital’s creatives for the good of the UK economy, in the wake of research that showed a shortage of affordable studios, rising rents and the insecurity of short-term leases threatens the future of the capital’s creative workforce. He cited research showing that in 2014, fifty-six per cent of artist studio sites were charging an average of over £11 per square foot; this has increased to seventy-nine per cent in 2017.

As artist Heather Phillipson pointed out alongside Khan’s call-to-arms, “Without affordable studios, we risk rendering art, like so much of culture, the preserve of a bland minority. If we want art to be inventive and inclusive, we must encourage artists… who may be from disadvantaged backgrounds or be working on the margins..” She added, “How we treat art may be one of the greatest measures of how we treat urgent and vital ideas right now.”

“How we treat art may be one of the greatest measures of how we treat urgent and vital ideas right now”

While many recognise the need for independent arts venues, London is an increasingly impossible place for most of them to survive. In the wake of Brexit, times are even more testing: a 2017 Arts Council study delineated “a widely held view… that funding for arts and culture is unlikely to be a priority for the government post-Brexit.” Many study participants spoke of the negative effects of lost EU funding and freedom of movement, leading to increased administrative costs, potential delays and a reduced talent pool of creative workers. The weakened pound is also a factor, as well as the fear that the Brexit result has made England appear to be a country lacking interest in intercultural exchange.

With its current unstable funding model coupled with London’s challenges, Jupiter Woods intends to shift its working model. But thanks to the area’s redevelopment, its future is uncertain. The goal is to use the spaces for more research-led purposes and meetings, considering broader ideas around how to work with others rather than just facilitating shows. “I want to push for more sharing of resources, and to collaborate on a much more practical level—not just on paper,” says Ongaro, who’s previously worked on collaborations between Jupiter Woods and big-name institutions like Auto Italia, South London Gallery and the ICA. “But it’s hard: we’re still working in the art world, and it’s highly competitive—it’s very hard to change mindsets and show that you can work positively by working together to find solutions.”

The original DIY, people-centred ethos of Jupiter Woods remains at the fore, with its focus on creating communities and knowledge exchange.

“How do you balance labour and freedom when the system expects you to be productive all the time? When you’re working with artists all the time, where does that research go?” Ongaro asks. “It’s about different ways of looking at the economies around work in financial and relational terms.” The project space has demonstrated that it can function without relying on the income generated from commercial gallery sales or official charity status. But, as she points out, that has only been through scraping by and with volunteer help. Ultimately, it can’t last forever.

The Horse Hospital

This deliberate eschewal of the art market is echoed in The Horse Hospital’s model, where they operate with a non-hierarchical staff structure and no formal job titles. They view their partnerships with artists, whether that’s in forming relationships, showing exhibitions or even just hosting one-off events, as collaborative ventures. “To my understanding, we had never had a predetermined agenda from the outset, aside from being an innovative space which programmes things that are otherwise marginalised and underrepresented,” says Letitia Calin, a member of their small team. “It’s not necessarily positioning itself in direct opposition to the institution but as an alternative to it.”

“How do you balance labour and freedom when the system expects you to be productive all the time?”

The Horse Hospital is not only unusual in its programming but in the space it occupies within the wider arts landscape. It sits in an otherwise no-mans-land area between independent, DIY and often-temporary spaces, and far more formal, established institutions like the ICA. What makes spaces like this and Jupiter Woods unique and vital additions to London’s art landscape is their freedom to operate and collaborate entirely on their own terms, with no set stream of grants, funders or stakeholders to appease. Calin describes this as “a shared resource rather than a service; it lies outside capitalist exchange values.” In the 1990s and early 2000s, many other independent spaces were forced to assume “business-like models to adapt to the neoliberal conditions needed for them to survive”, and many closed down.

She partly ascribes the Horse Hospital’s longevity to the way in which it offers support to artists and collaborators: “We’re not just a community in an abstract sense, we form actual friendships with the people we work with. It feels like quite a rare thing for institutions. It’s about actually treating people as human beings—with respect, openness, not assuming anything and actually listening. There’s no formality. Our process is about directness of accessibility and a basic level of humanity.” It is heartbreaking to see that spaces like these set up to fail, with increasingly impossible working models. “There’s no infrastructure to support organisations like this that aren’t commercially oriented,” says Calin. “There’s just no way we can see of existing in this landscape.”

However the founder and director of the non-profit Matt’s Gallery, Robin Klassnik, is far more optimistic. He founded the gallery in 1979 in Hackney as part of his artist studio. It has since moved through various locations, and is currently awaiting completion of its new purpose-built space in Vauxhall, which will house its exhibition spaces, archive and more. Like The Horse Hospital and Jupiter Woods, the gallery is effectively artist-run (Klassnik’s own work has been exhibited at sites including the ICA and Whitechapel Gallery). The key to the longevity of the gallery is simply that it “works consistently with good intellectual artists,” says Klassnik. “Most galleries come along then disappear, but we’ve never had pretences to be a commercial gallery.”

“We’re not just a community in an abstract sense, we form actual friendships with the people we work with”

Matt’s Gallery has not gone unnoticed. Klassnik received an OBE and Turner Prize commendation for his services to art, while The Guardian described Matt’s Gallery as “a little utopia” This is all in no small part thanks to its ability to spot groundbreaking artists, such as Turner Prize nominees Willie Doherty and Mike Nelson, Susan Hiller, Lindsay Seers and Benedict Drew. Similarly, the 2019 Turner Prize co-winner Tai Shani was a programmer at the Horse Hospital for a decade from 2006. Matt’s Gallery has always maintained a large physical space for its artists to work in alongside the show space. This decision is partly down to the fact that Klassnik’s “head works as an artist” rather than a curator, as he puts it.

When I ask if it’s harder today for artists to form spaces with a similar ethos to his, Klassnik argues that it’s quite the opposite. “Half of the art we talk about only happens on Instagram… a terrible machine”, he muses, arguing that it makes for fertile ground for interesting physical art spaces. Today’s artists all “want to be a celeb”, he laughs. “Nothing’s really hard if you truly believe in it and want to do it.” While he acknowledges that the cost of living has increased since the late 1970s, he is resolute that “to be a decent artist or gallerist you just have to believe in what you do.” How has he done it, then? “Passion, eating olives, and a very low salary.”

If only it were that simple. Olives will not be enough for the vast majority of spaces, and the Horse Hospital face the gloomy reality of becoming another casualty. Amidst a climate that is hostile not just to gallery spaces but to the very essence of independent culture, their unique platform for marginalized artists has never felt more important. It is a political environment that breeds a monoculture where only the privileged few are offered the opportunity to share their work. “It’s become increasingly clear that London has become about ‘creative industries’, not art—it’s for a certain class of people that can afford it,” Calin concludes. “There’s no real support for artists.”