Jonathan Baldock‘s spirited, hands-on works speak to the human condition, starting from a deeply personal place for the artist but connecting with a much more universal concern of what it is to be alive. While he typically moves between textiles and clay, often creating monolithic works which elevate their traditional materials or items that can be worn in performances, his latest exhibition—opening this week at Stephen Friedman Gallery in London—is a little more intimate in scale. For this show, the British artist has followed a strict format, creating multiple “masks” from clay, at a human scale, expressing a variety of moods through allusions to facial features. As the viewer, you find yourself trying to sense what might be going on in the face that stands in front of you. While the works were inspired in part by the simplified visual/emotional language of emoji, these masks are more complicated beasts which, similar to our interactions with fellow human faces, don’t always yield simple readings. I met the artist in his East London studio, to find out more.

“I really feel like they are a mirror to my mood. I think some of them are happy, some are a bit disturbed; stressed; anxious”

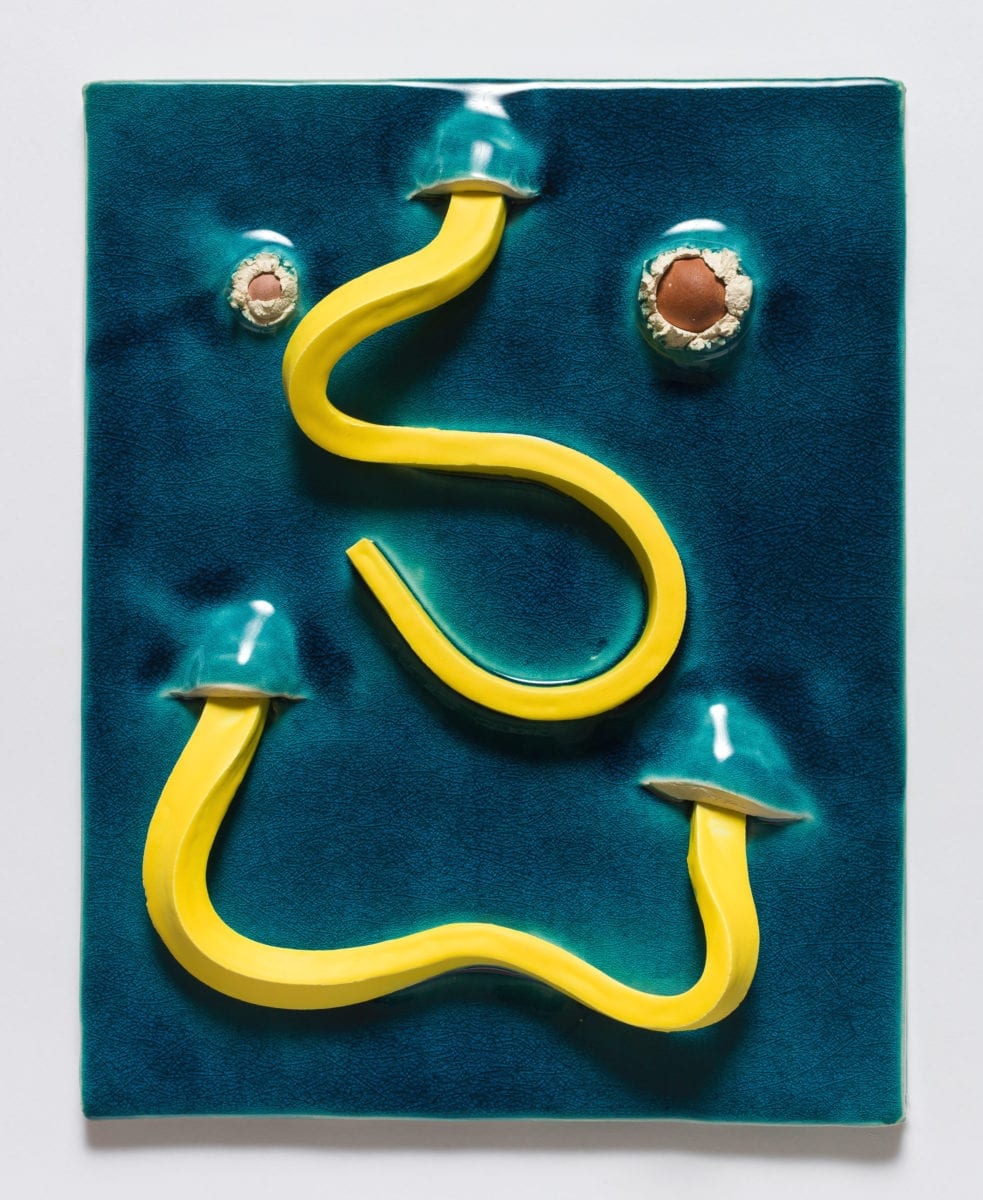

- Left: Maske 111, 2019; Right: Maske VII, 2019

Can you tell me a bit about the masks that you’ll be showing at Stephen Friedman Gallery?

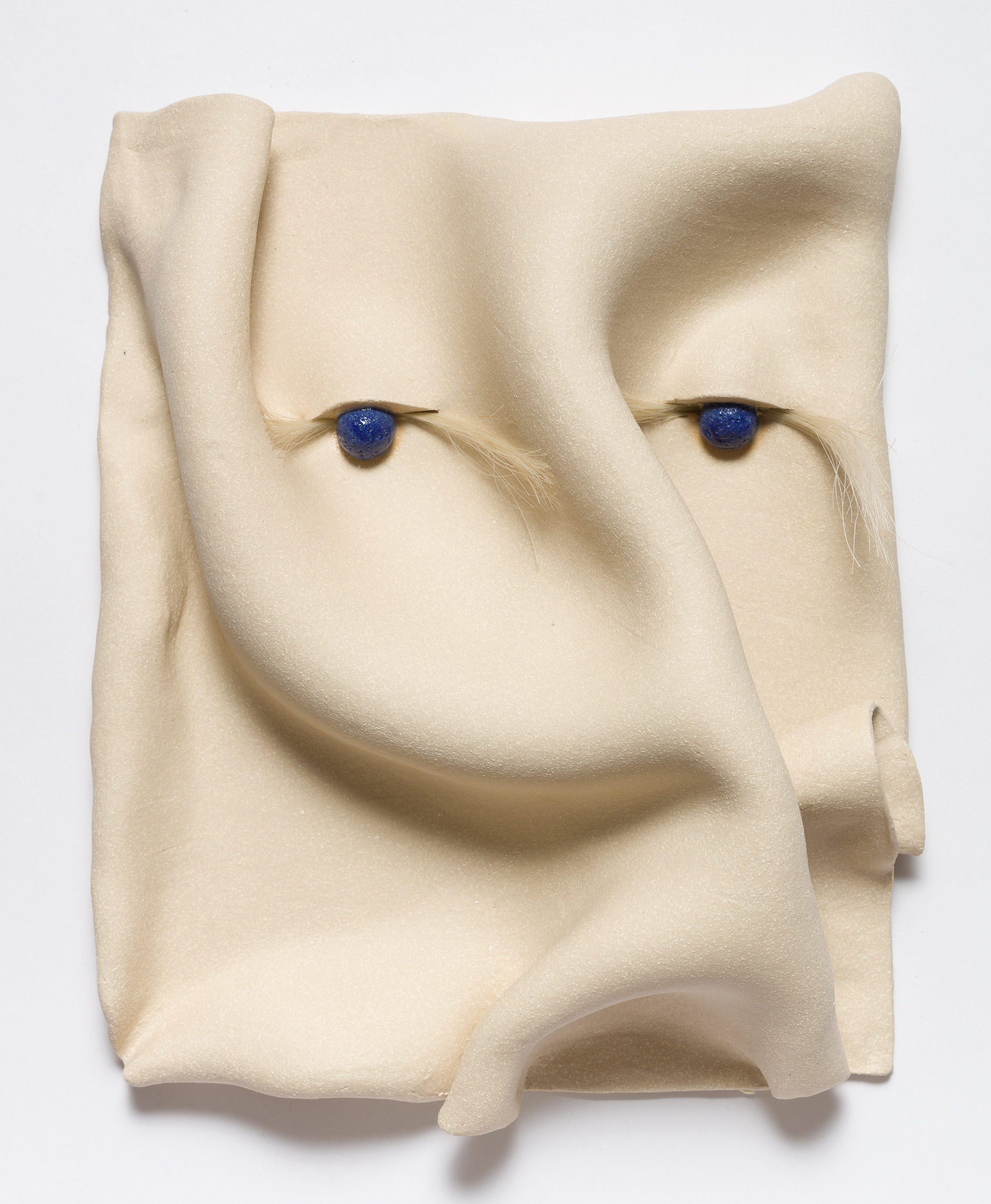

They are all made in the same format, they are all the same size, and then I change the clay, I change the glazes and I’m constantly experimenting with different techniques. I really feel like they are a mirror to my mood. I think some of them are happy, some are a bit disturbed; stressed; anxious. They can be very abstract but they all work on the basis that they are a mask. The thing I am constantly trying to play with is what you can do with two eyes and mouth. How far can you go within those contraints? And I’ve found out it’s pretty much endless.

I was looking at emojis a lot and thinking about the disconnect between a facial expression and how you feel inside. Emoji is the fastest growing pictorial language. Then I was also looking into the history of clay; I was in the British Museum researching ancient k-uniform, these Mesopotamian clay tablets that have a now extinct pictorial language, and I realised that they use clay as a means to communicate. These physical objects were performative as well, it blew my mind. Clay has this huge history since the earliest language, and in my work I want to be far more ambitious than making pots. So I mirrored that and started making my own language with clay. So these really are communicators of emotion.

Your work expresses all range of emotion, and often it has humorous elements too. What do you see the role of humour being here?

I make work that I think has to reflect and channel me. I use humour in the work in the same way I might use horror. It’s quite a theatrical way of making, and life is all of these emotions. If I am speaking about the body and what it is to be human, which I try to do in a very personal way, then I feel like I have to be all of those things. Things like humour… there is a hierarchy in the art world, and so being very serious and making work on serious topics is often put to the top, and is seen as having gravitas. But to have emotions and things like humour or love or all those more sentimental things… they are put to the bottom of the pile. And I can’t really get my head around why that is. I’m interested in the jester figure, the comic, and how we value that in society.

“These really are communicators of emotion”

I also love using colour but I feel the minute you start putting bright colours on things people switch to ideas of play, child mode. It really interests me how you can throw things out at people and if they don’t want to look any further, they really will just see it as that. Colour is joyful, there’s no doubt about it, but I’m always trying to play with the idea that there is more beneath the surface.

I do find your work really fun, it always puts me in a good mood, but there is often something a bit gross or uncomfortable about it as well. It’s like it connects with something that’s not quite right…

Children respond to my work really well, and I like that. When you’re a kid you can be drawn to dark things and gross things as well. Children pick up on taboos really quickly. You instinctively know that certain things are not to be said. There is something at the core of that which goes deeper to what it is to be human. And it’s interesting to channel that. We get so conditioned. As an adult you get consumed by finding your place, and you lose touch with some of the basics.

- Left: Maske XIII; Right: Maske XXIII

You obviously work with clay a lot, which feels like quite a connecting medium. It’s accessible and it’s something that many people will have worked with before, even if they are not practicing artists.

Although the work is based on me, my ultimate hope is that the audience responds to it. I am consciously thinking about how the audience will engage with it, how I can choreograph the viewer around it. I want the work to speak to people. It’s a visual language and all the materials I use are about the body and are a product of the body. Even though you haven’t made the work you can see how it was made. I do like the idea of the transformation of “basic” materials, but I hope you can connect with the physicality of it.

“I do believe in humble materials, there is a lot of power in them”

I used to do a lot of crochet with my nan, we’d watch TV and just crochet, and I loved it. So it was the sense of collective making, which is important, but also what I would describe as meditative making. Even though I did painting I always made work in textiles. I do believe in humble materials, there is a lot of power in them. People don’t often imagine that they could become something more monstrous and monumental and have that power. I want to make huge great towers out of ceramic, or monolithic sculptures, because I want the overlooked to be imbued with this power—and still have this fragility, which is very human: the cracks in the ceramic or the irregularity of a stitch.

It’s interesting that you mention crocheting with your nan, because you also spoke previously about how we used to live and work in a more communal way, and that we might be missing that connection as humans now. Do you hope for this more traditional way of people making things to be communicated in your work?

I have been working with textiles for over fifteen years and I am really interested in the history of making textiles and what working in textiles means. Since the Industrial Revolution we have had a huge disconnect with how we value fabric. With fast fashion its hard for us to see how important textiles are. It’s why I started learning how to spin my own wool and to have that connection. It really gives you a whole new appreciation of it. I use these raw hessians, which are a rustic ancestor of the original. I also use felt, which would have been heat pressed fur or wool many years ago. And then clay has just taken off in such a good way recently. I don’t know if it taps into something very primal, which is your body in the earth. I switch between the two mediums; when I have my textiles out I can’t use clay because it’s so messy. But if I have a bit of a block, I will get the clay out. I work in such an intutitive way with the clay.

Jonathan Baldock: Personae

27 September to 9 November at Stephen Friedman Gallery, London

VISIT WEBSITE