Keith Haring in subway car, ca. 1984. Photographed by Tseng Kwong Chi

Keith Haring’s artwork triggers a kind of 1980s nostalgia that is immensely “on trend”. Somehow, it also transcends pure retro trip. That’s partly because Haring’s exuberant, emotionally direct blitz of expressions (throbbing hearts, human figures, “radiant babies”, barking pups, cartoon mice, triple-eyed spirits, UFOs, pop energy and political slogans) has deeply filtered into modern fabric, from fashion prints to club flyers. It’s also because his work arguably still represents pop culture at its most febrile.

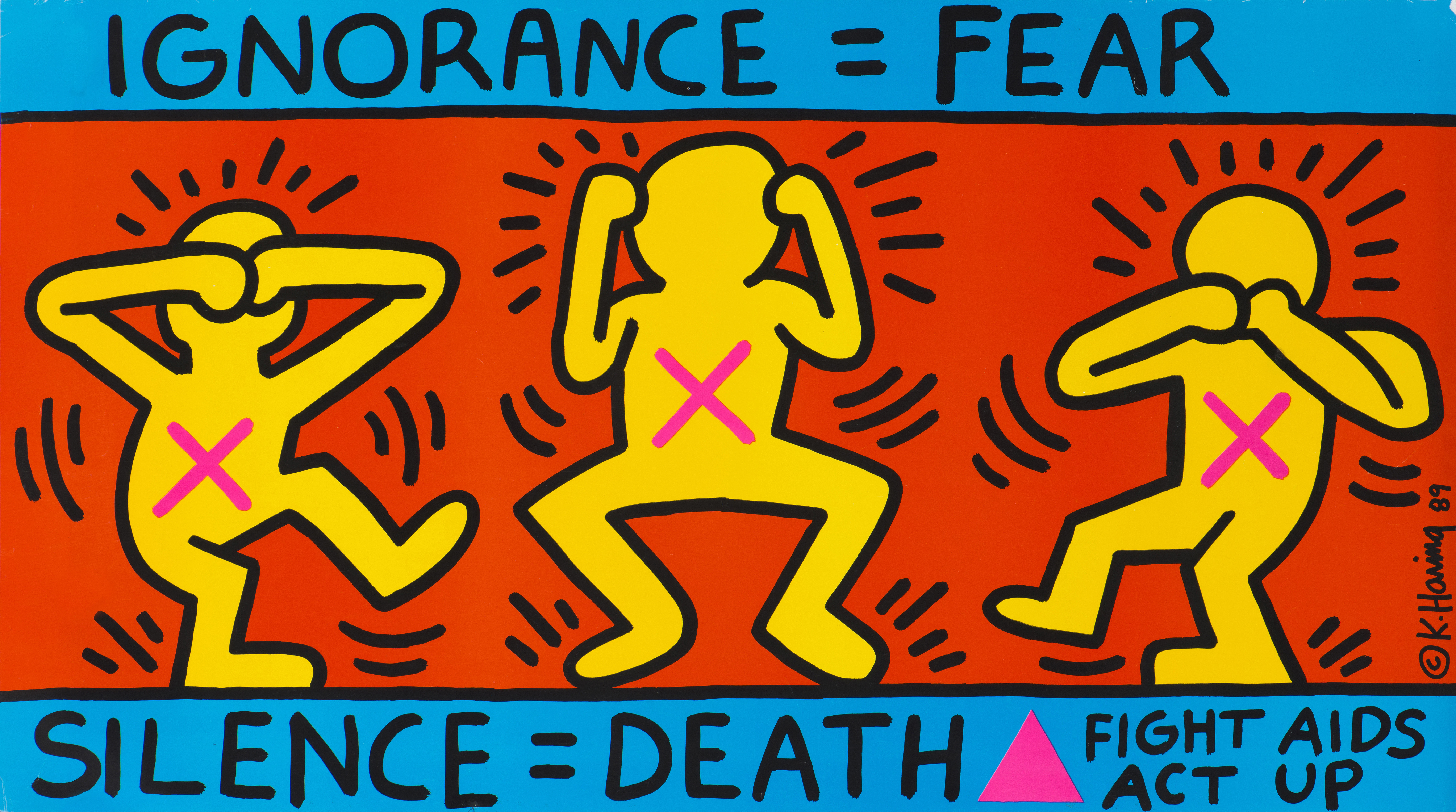

The urgency of Haring’s imagery is invariably associated with the brevity of the artist’s own life; he was just thirty-one when he died from Aids-related complications, in February 1990. In 2019, it seems strange to think that a major-scale exhibition dedicated to Haring’s work has never taken place in the UK before now. At Tate Liverpool’s newly opened show, much seems incredibly familiar, and nothing appears faded: the boldness of his lines, the invigorating colours, the way-out weirdness, the explosive joy and calls to action. Haring’s work summons an energy that dazzles in a chaotic universe (then and now), and it locks its viewers in a brilliantly inclusive rapport.

- Untitled, 1983

As a young kid in eighties Britain, I first really grasped that art could belong in the everyday, and that it could flourish anywhere (as opposed to being sealed in formal institutions), because of Keith Haring. I read about his work and New York scene, and his collaborations with pop stars and DJs, in youth titles like Smash Hits

magazine. His activist statements, championing social, racial and LGBTQ equality, and campaigning for education about drugs and HIV awareness, felt vital and inspiring, and sometimes unsettling. The atmosphere at school and in mainstream news reports definitely wasn’t “woke” back then; I recall daily casual racism and homophobia—as kids, we’d edge our way around this excruciatingly, but we didn’t really know how to challenge it. Pop music and pop art presented a much stronger example. As I hurtled towards my teenage years, it seemed like the whole world was coming of age.

“At Tate Liverpool’s newly opened show, much seems incredibly familiar, and nothing appears faded”

As a grown woman returning to Liverpool (a city where I’d literally taken my first steps as a baby), I walked into Tate to find myself wishing I could embrace or dance alongside Haring’s figures, or transfixed by the more disturbing tableaux. Obviously, so much of Haring’s art was created for streets, stations and public spaces; crucially, this gallery setting feels sympathetic, not stifling. There’s a sharp contrast of intimacy and scale, and a real thrill in experiencing the physicality of his original work up close, whether it’s late-seventies art school sketches (with bodies and organs emerging from harsh marks), snappy graffiti stencils (“Clones go home”) or beautifully preserved chalk-on-paper early-eighties NYC subway posters. The free range of materials is a total delight; the city itself becomes art—in one corner, Haring’s ink designs are tattooed over a yellow cab hood; elsewhere, his babies crawl over subway maps, and his shapes and dates sprawl over billboards and construction tarpaulin.

In a 1985 interview (with Sylvie Couderc), Haring described art as “something that liberates the soul, provokes the imagination and encourages people to go further. It celebrates humanity instead of trying to manipulate it.” There is fantastic happiness and humour in these works, and also a stinging sense of fury; when we see figures rise against apartheid and other injustices, sometimes snapping the shackles placed on them, they do not feel like dusty history lessons, but vividly pertinent prompts. As Haring’s friend and Dancetaria peer Madonna noted of his work: “There was a lot of innocence and a joy that was coupled with a brutal awareness of the world.”

Haring’s visuals can never really be divorced from music, rhythm or nightlife. Throughout this show, we hear strains of post-punk riffs and clips from seminal hip hop film Wild Style; we see Haring body-painting patterns onto Grace Jones (snapped by Andy Warhol), and succumb to the hypnotic patter of Art Boy Sin (1979). The physical centre-piece of the Tate exhibition is a recreation of Haring’s “black-light” installation from 1982; inside this compact space, it actually feels like the club beats (taken from a new compilation album on Soul Jazz records, The World Of Keith Haring) could have been louder and more bass-heavy—but the UV-lit paintings inside definitely pulse with love, life and heat.

“It celebrates humanity instead of trying to manipulate it”

Invariably, there is an uneasy end-note. Haring travelled widely (albeit never to Liverpool before now, it seems), and connected with technology as much as he critiqued it; it’s impossible not to wonder where he might have taken his inspirations had he lived longer, particularly when you view the increasingly complex abstractions of his late-eighties works, which reveal the global breadth of his inspirations.

The final room at Tate centres on his HIV/Aids activism, and it is almost head-spinningly evocative, including a series of ink-and-gouache drawings which depict the HIV virus as a kind of rapacious devil sperm, and his powerful public information posters for international grassroots group Act Up (“Silence = Death”). There is also further important context, in documentary footage taken after Haring’s death: Act Up’s harrowing Ashes Action protest from 1992, where bereaved campaigners marched with the ashes of loved ones failed by government prejudice and neglect, and literally scattered them before the White House. It feels right that we’re left feeling unsettled, and also invigorated—there is seemingly infinite lust for life in Haring’s images; they urge us to celebrate and activate, and they swirl before us in some kind of perpetual motion.

![Keith Haring, Untitled 1983 [X74582]](https://elephant.art/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Keith-Haring-Untitled-1983-X74582-1200x1183.jpg)