A large-scale painting of a bearded figure with black eyeliner, delicate straps on their shoulders and intense blue eyes extends across one wall of Manuel Solano’s small basement studio. The painting is based on the cover for Peaches’s 2003 album Fatherfucker, but this offers a gentler, more vulnerable version of the gender-blurring singer. “I’m deriving this painting from a portrait I did of my aunt wearing pearls. She was not very feminine physically, she was clunky, and I feel like she had to look girly and coy in order to play the part,” explains Solano, who identifies as transgender. “This painting of Peaches is the opposite, like stepping out of femininity and affecting masculinity to convey this grey area, this gender fluidity, which is something she’s always talking about in her music and in interviews.”

“I’m still alive and I’m still a big personality making big work”

Stuck onto the surface are pipe cleaners, tacks and threads. At a glance, their function could be decorative, adding textural elements to the painting; in fact they are vital tactile markers for Solano, who became blind six years ago aged twenty-six due to an HIV-related infection. At that point Solano assumed their career was over, but a friend persuaded them to take up their brush again. The result was a series of raw, vivid acrylic works on paper called Blind Transgender with Aids (2014). “The title was a provocation. I thought if anybody pays attention to these paintings it’s going to be either through morbid curiosity, like—‘Oh, let’s see what a blind person paints’—or through pity, and I was not going to have either of those. I’m still alive and I’m still a big personality making big work,” the artist tells me as we sit side by side on a sofa in their studio in the northern suburb of Satelite.

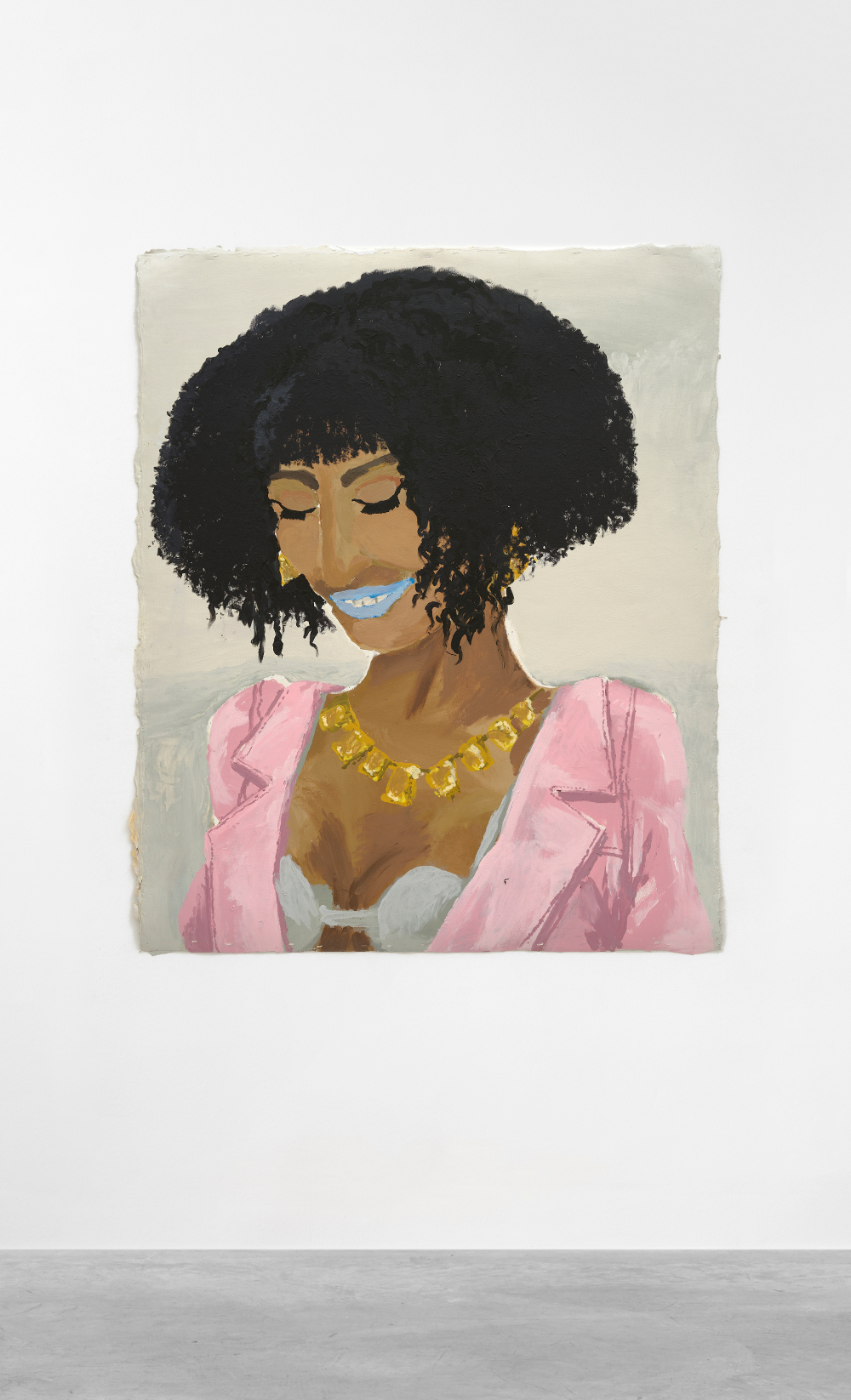

These expressive paintings span scenes, portraits and text. One diptych, Aquaerobics, depicts an outdoor pool class under a blazing sun, vibrantly conveyed in thick daubs of colour. Among the portraits there’s a lithe, ageless Cher in a Joy Division crop top with a massive tangle of curly hair, the actress Fairuza Balk, whose enormous red toothy mouth sails across her face like a listing ship, and a brave self-portrait, What’s Left Me, showing Solano’s body riddled with scabs. When the series was exhibited in a pop-up show, it garnered considerable acclaim: Solano was given an exhibition by Karen Huber gallery in Mexico and selected for the 2018 New Museum Triennial, an influential indicator of artists to watch. In the past few months Solano has had a show in Berlin, currently has their first solo US museum exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami and will be in a group show at Palais de Tokyo in Paris this summer.

Art addressing identity politics is rare in Mexico. While this is beginning to change, understanding of trans issues remains limited. Solano only began identifying as trans just before becoming blind and still feels confused about it. “I feel like I’m isolated from everybody. I’ve lived all my life as a gay man and I don’t feel like that’s worked out for me. I feel like I’ve never been comfortable in my own skin and everybody’s the opposite sex.” Solano didn’t knowingly encounter the gay community until the age of eighteen. The 2017 diptych Blood and Homosexuals is a humorous dig at narrow social attitudes, specifically those of their mother’s friend, who years ago asked them to make a painting “but nothing with blood and homosexuals”. It features a portrait of an androgynous figure alongside a squatting naked creature dripping blood, an interpretation of Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son (1819–23).

“If anybody pays attention to these paintings it’s going to be either through morbid curiosity, like—‘Oh let’s see what a blind person paints’—or through pity, and I was not going to have either of those”

The artist lives in an apartment above the studio, in the neighbourhood where they grew up, now largely cared for by Solano’s mother Claudia, an amateur photographer. She had given up her practice to raise her family but Solano and she have begun collaborating together. Solano’s family supported their creativity. Their obsession from an early age with fame and pop culture is reflected in the paintings. Michael Jackson was a particular idol. “It was clear he was super powerful. He could take his creativity wherever he wanted and people followed him. Instinctively I wanted something like that.” Solano attended La Esmeralda art school in Mexico and further studies in Lyon, France, where they were frustrated by having their work labelled as “homosexual”; Solano considered it to be broadly about the human condition and loss. “I didn’t realize how personal it was until I became blind. I see now that it was always about me, my loneliness, my feelings of not fitting in.” Even where Solano’s art draws heavily on films and music references, it’s always rooted in their own experiences and emotional responses.

A month before going completely blind, Solano made the video El Cuerpo Perdido (The Lost Body) in which they perform a slow painful strip before a webcam, removing their clothes to reveal a frail body ravaged by sores, before breaking down in tears at the end. Watching it evokes profound sorrow and discomfort at our own invasion of their privacy. “It feels almost too personal to this day,” Solano agrees, but says they needed to “put it out there”.

“I think I was put to a test and I passed it but I want to keep it a catalyst and not a limitant”

As horrific as the experience of blindness has been, Solano has wrung positives from it. “It helped make clear to me what my work was about and what I want from my work,” they note. It also tapped untested resources. When someone sent them a video profiling a blind painter who used tactile markers, without explaining the methodology, Solano taught themself and also developed a system for mixing colours. “I always keep my paints in the same spot and have a very limited palette: two blues, two reds, two yellows, two greens, a black, a white, one basic flesh tone and one basic brown. I make all of the combinations from that.” Having an assistant has helped, but they still find painting by touch exasperating and time consuming. Yet these recent paintings, characterized by nuanced brushstrokes and greater depth of perspective, display an assurance that was absent from the powerful but rudimentary Blind Transgender with Aids series, which was dashed off, sometimes several in one day. Whereas those paintings were inseparable from Solano’s biography, the works now stand on their own.

Among the five paintings submitted for the New Museum show, Solano presented I Don’t Know Love, featuring themself with cropped red hair and dungarees as Milla Jovovich’s character Leeloo in the 1997 sci-fi fantasy The Fifth Element. Against the backdrop of a bungalow surrounded by trees silhouetted in the setting sun, the protagonist stares fixedly over the viewer’s shoulder. The lonely atmosphere distinctly recalls Edward Hopper. Solano captures a similar ambivalence in Basement, their first greyscale painting, based on a scene from the 1999 horror Blair Witch Project. The painting, which wasn’t included in the final New Museum show, depicts a solitary figure with his back to the viewer. “That was despair, just wanting to get out of this basement. With all my success, I’m still disabled living in this situation where I depend on others for the rest of my life.”

Solano knows that art is their ticket to greater independence. And in pushing themself so hard to overcome the loss of sight, Solano seems to have discovered a new painting voice. “I think I was put to a test and I passed it but I want to keep it a catalyst and not a limitant,” Solano says. “I would say I have found a voice but it’s not the only voice. And it’s going to keep changing.”