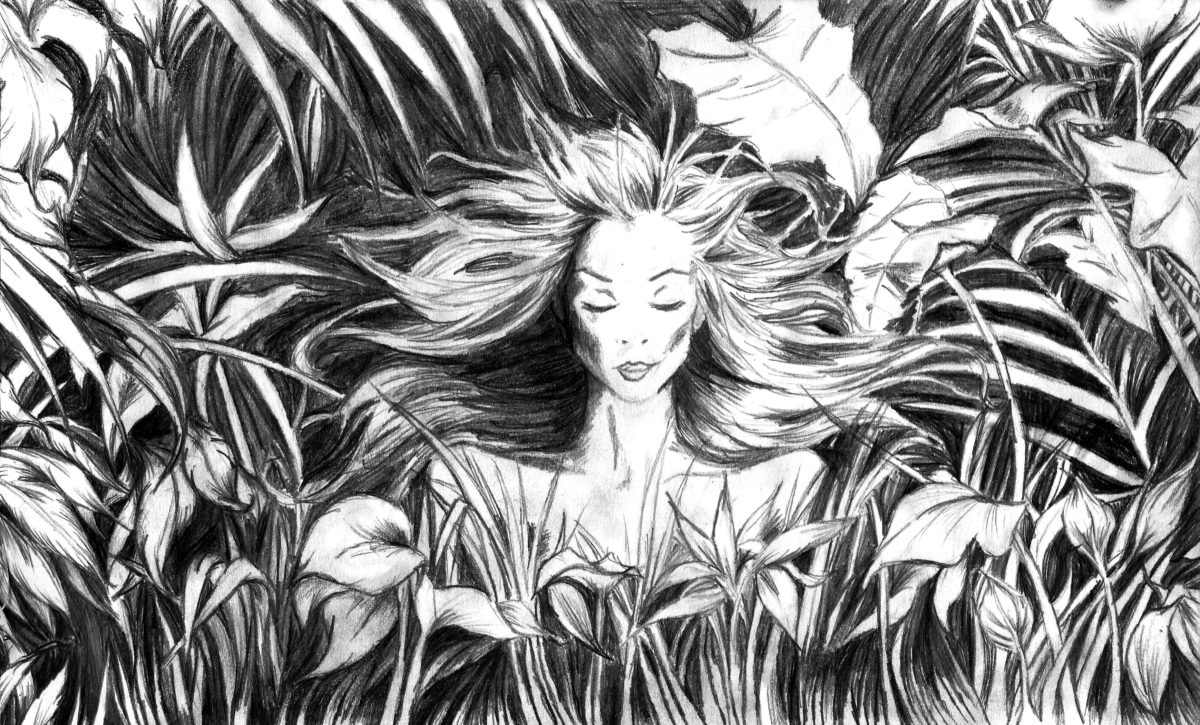

Eve, 2019

Laura Jean Healey is an award-winning filmmaker who uses the medium of film to explore the nature of the cinematic experience. Her particular focus is on the role and objectification of the female form on the screen. Her holographic film installation, The Siren (2012), shot underwater in slow-motion, won the Passion For Freedom Gold Film Award in 2014. She has recently been working on a new project, The (Un)Holy Trinity, exploring the representation of three legendary “unnatural women”: Lilith, Eve and Salome.

Can you summarize the concept behind your forthcoming work—a triptych of digital films, portraying Lilith, Eve and Salome, entitled The (Un)Holy Trinity? What do these three women represent, both in existing legend, and for you?

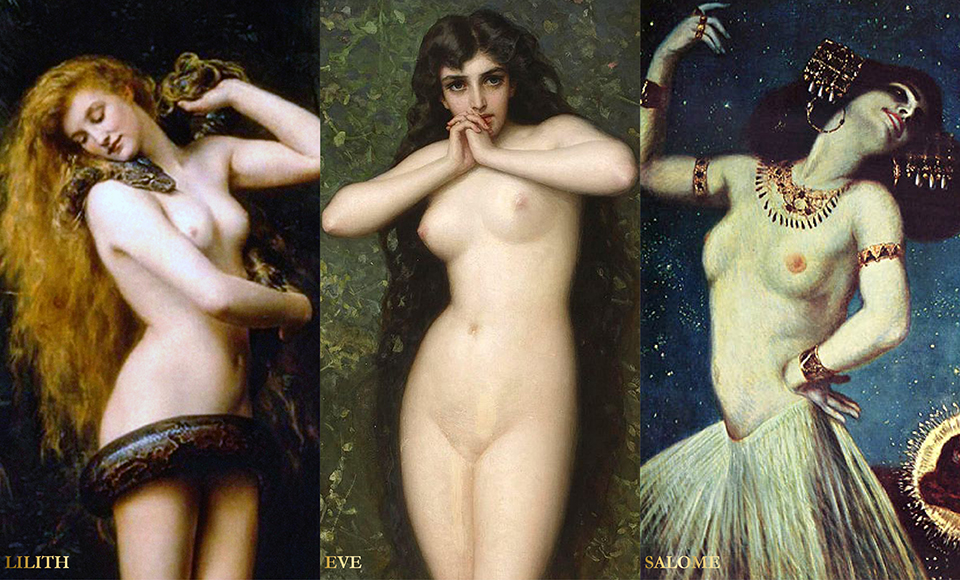

Throughout history, these three women—taken directly from the Bible (Eve and Salome), or inspired by the inconsistencies found within the book (Lilith)—have been vilified for their “unwomanly” actions and used to serve as a warning as to how destructive female sexuality can be if left unchecked.

According to Jewish lore, Lilith was the first wife of Adam. She was made in the same manner as him and considered herself his equal. When he wanted her to lie beneath him, she refused to submit, enraging both Adam and God. In her frustration, she fled from paradise and, in so doing, became a succubus (temptress of innocent men), breeder of evil spirits and child-murdering monster of the night.

“Throughout history, these three women have been vilified for their ‘unwomanly’ actions and used to serve as a warning as to how destructive female sexuality can be if left unchecked”

Eve, unlike Lilith, was not made as an equal to Adam. Even though both she and Adam ate from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, bringing about the Fall of Man, it was Eve alone who bore the ultimate responsibility and was punished with the pain of childbirth and being subjected to her husband’s will.

Salome was a young virgin, who danced for her uncle/step-father, in order to win the head of John the Baptist. In her desperation to possess him, she exerted a more dominant, “masculine” sexuality and was punished for this “monstrous” nature.

I have always been fascinated by these women’s stories. It is these cautionary tales of the “unnatural woman” that have been used to justify women being held back throughout history. Even today, women are often still inherently judged by these unfair and contradictory standards.

- Lilith, 2019

Each of the films comprise one single high-speed shot.

Yes. We are shooting with Panavision’s Phantom Flex 4K Camera at 500fps. This means that eleven seconds of live recording time for each, when played back at 25fps, will become just over three minutes of film.

What are some of your inspirations for the films’ visual styling?

The films will have a highly-stylized, cinematic look. The protagonists will be surrounded by rich foliage to create the feel of a painting—reminiscent of the Pre-Raphaelite and Symbolist art movements. I will use film noir lighting to create not only a sense of depth, but to contrast this darkness against the beauty of the image and invoke an uncanny sense of the foliage emerging from the shadows. The use of a long lens and a shallow depth of field will heighten the dream-like quality of the films, which will contrast jarringly with the innate violence of each of the women’s actions.

The hair of each character will also be very important. Within the history of Western art, hair has traditionally been associated with sexual power. Each of the women will have long, wild hair to convey her innate passion. Lilith’s hair, in particular, will move like snakes, writhing as it flows over her shoulders, echoing the many times she has been depicted in art as the snake that tempted Eve. Eve will have apple blossoms and leaves entwined in her hair, and Salome’s hair will be crimped into a wild mane, reminiscent of a lion, signifying her wild and savage nature.

The films will be premiered in collaboration with Sedition, in central London, on 7 March 2020—the eve of International Women’s Day. How significant do you feel this project is in the light of recent movements such as #MeToo and #TimesUp?

Highly significant. While movements such as these have helped bring issues to the forefront and give a voice to many who felt as though they had none, we still have a long way to go before women have the same rights and opportunities as men. By exploring how these cautionary tales have been used to restrict women throughout history, I aim to reveal the inherent hypocrisy and challenge these attitudes.

“It is these cautionary tales of the ‘unnatural woman’ that have been used to justify women being held back throughout history”

Your previous work, The Siren, which won the Passion For Freedom (PFF) Gold Film Award in 2014, and was recently used to raise money for the festival, was significantly censored by online social media platforms. How does this make you feel?

PFF’s film to promote their crowdfunding campaign used a short excerpt from The Siren, which depicts a naked woman underwater. It was taken down by Facebook, which considered it “unsafe” and in breach of its community standards. The only way that my film contravened these standards was the fact that you can see a woman’s nipples (apparently the vagina is OK, but not the anus, buttocks or female nipples). Facebook does, however, supposedly “allow photographs of paintings, sculptures and other art that depicts nude figures”. As The Siren

is an artwork, it was not in breach of any standards and, by removing it, Facebook was in breach of its own standards. After unsuccessfully trying to contact Facebook myself, PFF reached out to a number of reporters, and, within a few days, the film was reinstated and we received a generic message apologising for the “mistake”. While the whole situation left me feeling incredibly frustrated and helpless (there was no warning before the film was removed, nor any way in which we could challenge the ruling), what truly troubles me is the hypocrisy and blatant sexism that Facebook exhibits towards women. That my artwork was considered to be “unsafe” merely because it depicts a naked woman is a rather dangerous concept to be faced with in 2019.

You are launching a crowdfunding campaign. How critical is this to the making of The (Un)Holy Trinity?

I have applied to the South East Creative Cultural and Digital Support Scheme, which if successful, will give us 35 per cent of our budget. I am also working with Greenlit, a crowdfunding platform dedicated to film projects, to complete the budget and enable me to push this project further than any of my previous ones. You can find out more on the campaign or project websites.