What artistry lies behind a dinner party? Throughout history, this food-focused act has involved elaborate performances and immense decadence, from the outrageous sugar sculptures beloved by the royal court at Versailles, to the “experiential” dining offered by celebrity chefs such as Heston Blumenthal

—I have, I confess, listened to an iPod playing the sound of the sea, while eating sashimi and edible sand.

Gathering to eat is often considered the source of community, discourse and celebration. The notion of artists, writers, revolutionaries and great thinkers coming together over a dish and lashings of booze is celebrated the world over, and despite the fact that the basic instinct to feed those you love should be the most natural action in the world, a dinner party can often be an elitist event, enjoyed only by a select few.

Esther Choi’s new culinary book Le Corbuffet was inspired by a menu crafted by László Moholy-Nagy for Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus visionary, before he relocated to the USA in 1937. The “Gropius Dinner” includes turtle soup, boiled scotch salmon in lobster sauce and iced nectarine melba. It was a glamorous affair, according to the author, and she was so inspired by this bill of fare that she decided to reconstruct the dishes for a group of friends and subsequently began creating her own courses designed to capture the essence of various artists and architects (and narrowly avoided murdering a turtle in the process).

“Each page features what is tantamount to food porn”

Choi refers to her dinner parties as a “social experiment”, as well as a “domestic food situation”, which became known as Le Corbuffet, a pun derived from another great (and undeniably sexist) architect, Le Corbusier. Choi insists the word play is a feminist action (one wonders how, exactly) and her over intellectualization of a good old knees-up is not entirely convincing. I’m not sure that making elaborate dishes for your mates is a “form of resistance”, especially when compared to Michael Rakowitz’s Enemy Kitchen food truck, or JR’s dinner table staged over both sides of the US-Mexican border

.

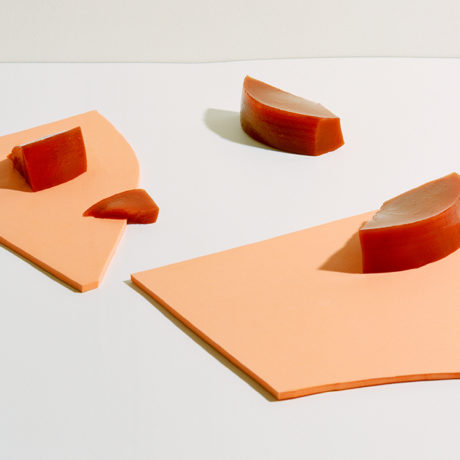

- Left: Elsworth Kelly Tomato Jelly © Esther Choi / Prestel Publishing; Right: Rhubarbara Kruger Compote © Esther Choi / Prestel Publishing

However, if you look beyond the theorizing and get to the actual recipes, you will be pleasantly surprised. Each page features what is tantamount to food porn. Meats are piled delicately, salads are scattered, and jus is gently drizzled in a manner that transcends traditional food photography. It’s utterly mouth-watering, and all these shots have been constructed and snapped by Choi herself.

The methodology for each dish is mixed, flitting from the aesthetic considerations of Ellsworth Kelly via tomato jelly, to the conceptual basis of Lawrence Weiner (guess what food stuff she used), all the while shoe-horning in rhyming or wittily crafted titles. Some might call the approach incongruous, but it really doesn’t matter, because it’s damned good fun.

William Eggleston Strata © Esther Choi / Prestel Publishing

The joy sparked by recognizing each artist-drawn inspiration is reward in and of itself—Flan Flavin! Fischi and Weisscream! Robert Rauschenburger!—and most recipes, despite their extravagant staging within these pages, are within the reaches of a so-so cook. There is an exuberant, almost frenetic approach to this recipe collection that is strangely approachable in its utter madness. Whether or not anyone will actually make these dishes is debatable, but you can happily enjoy this book as a bizarre work of art in and of itself.