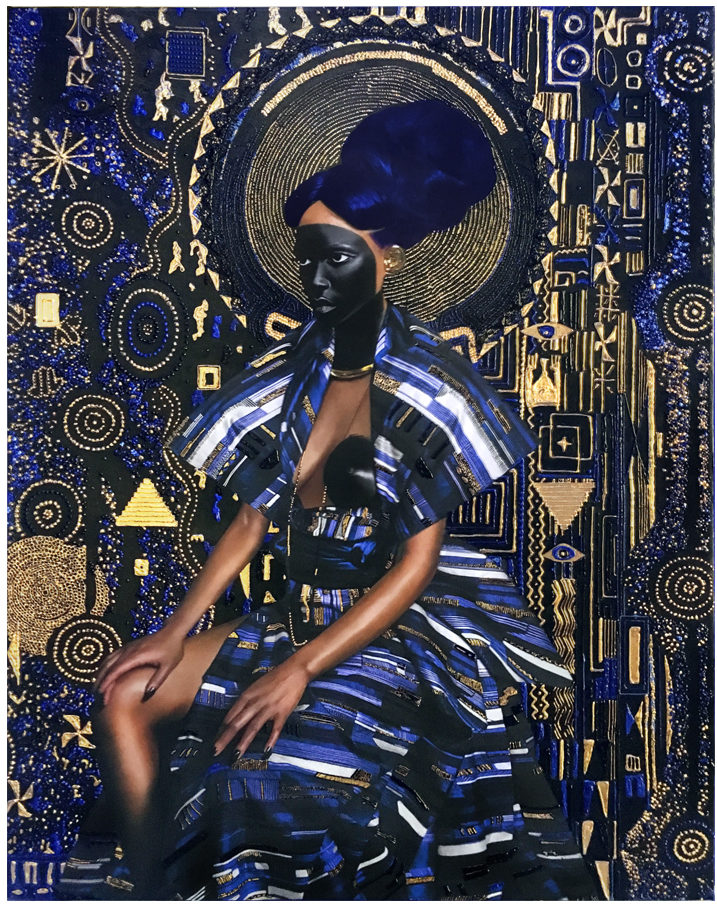

Lina Iris Viktor’s richly complex painting Fourth features on the latest cover of Elephant magazine. Informed by the mythological figure of the Libyan Sibyl, a prophetic priestess who became affiliated with the Abolitionist movement, it is inscribed with the interconnected histories of Liberia and the United States. I spoke to the artist about the inspiration behind the imagery and the importance of expansive storytelling.

This piece forms part of the A Haven. A Hell. A Dream Deferred series, which debuted at the New Orleans Museum of Art in 2018. Can you tell me a little about the original impetus for this body of work?

People might assume it is a personal investigation into my Liberian roots, but it is really more of a study in human behaviour and how, as a society, we have created situations that have been very detrimental to large numbers of people. It forms something of a cautionary tale. I wanted to unravel the narratives that connect Liberia with not only American history, but African American history.

I don’t think Liberia’s story is that well known [the modern-day country began as a settlement for “repatriated” former slaves from the United States] and people always say that it was not colonised, though I would beg to differ. It just wasn’t colonised by white Europeans! I was also told that there was no connection between Liberia and New Orleans, and the history of this entire migration is very poorly documented. However, I discovered that John McDonogh, a local slave owner, was part of the American Colonization Society that organised repatriation. His statue has recently been pulled down as part of the Black Lives Matter movement.

“An Italian painting of a Greek prophetess might seem completely removed from the story of Liberia and America, but all of these myths and narratives were imposed by European culture”

Fourth focuses on a central figure, which is based on the ancient Greek oracle Sibyl. What significance does she hold?

During the abolition of slavery, a lot of artists and writers exhumed this image of the prophetess—known as the Libyan Sibyl—who was the arbiter of ill-fated futures. Her likeness is found throughout history and in museums around the world, but she came to represent the fate of the African people and was aligned with figures like Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth. This particular composition is inspired by a mosaic, created by the Italian painter Guidoccio Cozzarelli in the 1400s.

She holds the book of knowledge in one hand, and a flower in the other. This is a reference to Chris Ofili’s Within Reach exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 2003. He used floral motifs to explore the idea of Black utopia and pan-Africanism, which has its roots in the activism of Marcus Garvey. However, while he never fulfilled his mission, Liberia is a real story of people repatriating back to the continent. So, I am approaching a different way of dealing with an issue that many other artists have considered.

You also paint parts of your body black, in this instance your face. Is this a specific commentary on the racialised idea of “Blackness”?

It began as a very intuitive process. There wasn’t one reason, even though I knew it could be read as provocative. I don’t see it as a direct response to something like “blackface” but rather the idea of pure black being a thing of beauty. It is a continuation of the ideas I explored in the painting Yaa Asantewaa [named after the Ashanti warrior queen] which is a commentary of Black figures in art.

Fourth is a densely rich multimedia work that features a huge range of patterns and symbols, not to mention resin, acrylic, ink, photography and 24 carat gold. How do you go about building such a complex composition?

I always begin by figuring out the concept or the narrative, which is based in a lot of research and sourcing materials, particularly textiles, which inform a lot of the motifs I create, because they are all inscribed with different information. That is followed by a photoshoot, where I intuitively wrap the fabrics around my body. After the very time-consuming editing process that image is printed, and I begin building the world around it. Much like painting by numbers, I consider how all the colours and patterns come together and are placed to tell that visual story.

There is a real sense of excavation in your work, you could spend hours peeling back every layer and discovering a new reference and subsequent story.

I strongly believe that everything is interrelated, but sadly we are all taught to compartmentalise our lives. In this instance, an Italian painting of a Greek prophetess might seem completely removed from the story of Liberia and America, but all of these myths and narratives were imposed by European culture. It is similar to the lore surrounding the genius of the artist, this idea that what someone creates must be unique and highly singular. When in fact, it is the sum of so many different sources of knowledge.