“I still have a suitcase in Berlin,” crooned a world-weary Marlene Dietrich in 1955. She was pining for the ghosts of an absinthe-fuelled Weimar-era German capital, but it was all but gone by then. And while the glitter of that particular Berlin—snuffed out by a dictatorship, bombing, and decades of division and economic frailty—never quite returned, the city is still caught by a fever of creative energy in transience. Crossing its canals at any time of the day, its sidewalks and parks are ripe with leisure-seekers. The sense of fleeting romance encompassed in Dietrich’s lines still carries in the air.

Acoustically, Berlin and its bricolage of imperial bel-étages, factory-cum-clubs, and Soviet-era promenades are tinned with the hard-edged sound of days-long parties rippled by electronic music. Many who visit or live here can recall racing around the city’s wide expanses, Lola’s shock of red hair from the 1998 techno-laced thriller Run Lola Run trailing like a shadow. She tears around Berlin corners trying to save her lover from a sequence of fateful options, in a movie all about choices.

I remember hearing Âme’s pulsating Rej at Berghain within the first months of moving to the city. Its harrowing beat washed over me in a transcendent experience (the club is nicknamed ‘church’). In that surreal moment where the track glides up a cliff of building sound, before crashing back into a minimal flicker, I knew that I wanted to carve a reality for myself here. Back then, I only had a large roller bag worth of things stowed at a friend’s apartment in the old west neighbourhood of Neukölln. I was thriving off a budget diet of €2 Turkish pizzas, supplying my nights with Späti-bought Club-Mate and small bottles of vodka––well aware that I was a cliché of Berlin tourism, but still not quite able to escape its sweaty clutches.

“Berlin is a place for self-actualisation, and it has emerged as such time and time again”

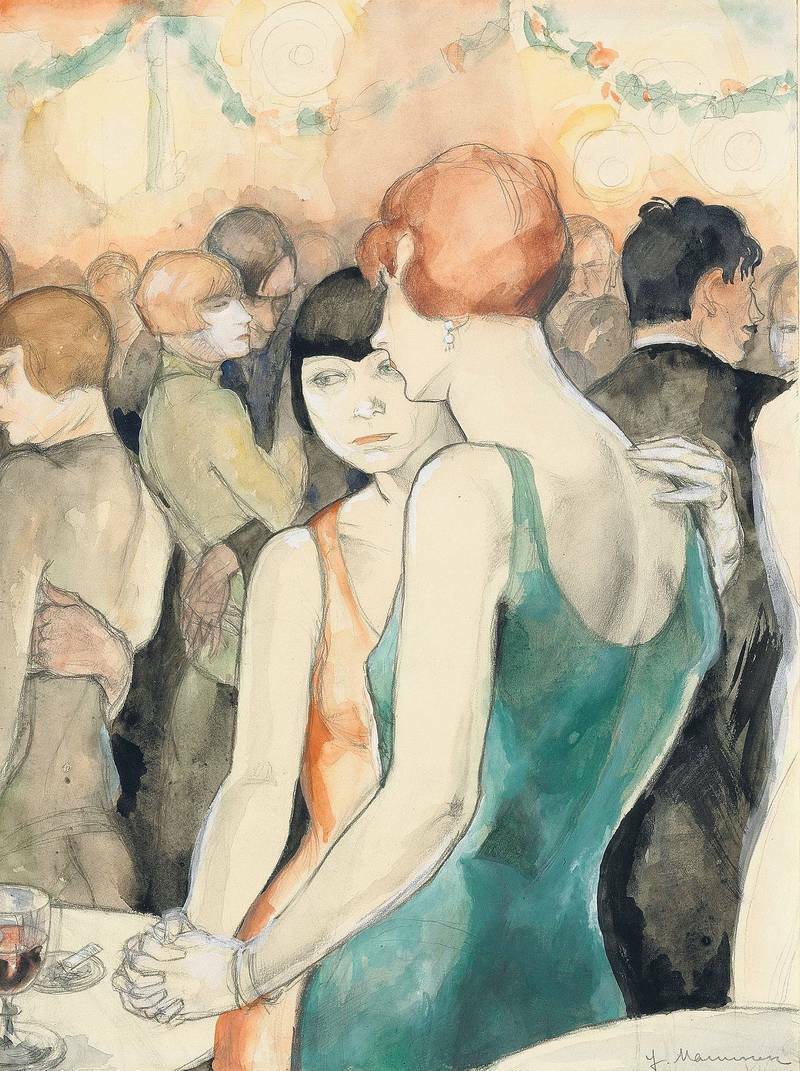

Berlin is defined by its locals and a storied past, but it has a historic allure to newcomers. Like Dietrich, people the world-over seem to have an attachment; one finds an easy enough membership here. I can’t help but compare the bodily tensions in Jeanne Mammen’s 1928 watercolour Zwei Frauen Tanzen (Two Women Dancing), to Wolfgang Tillmans’ photography of parties from the early 1990s, where men are embraced in reverie. Their representational rules may be different, but they echo a similar spirit. Berlin is a place for self-actualisation, and it has emerged as such time and time again.

What calls to its lineage of free-spirited visitors, perhaps most famously epitomised by Sally Bowles, the English-born cabaret dancer in Christopher Isherwood’s 1939 novel Goodbye to Berlin (given wider fame by Liza Minnelli in the 1972 movie Cabaret), is the very idea of being able to come and go under the city’s fluid identity. Bowles is last heard from in the book by way of a postcard from Rome with no return address, but she has a suitcase here too.

Maybe, then, it is most fitting to end this trip at one of the most iconic sites in the city: Tempelhof, the former Nazi airfield which is now a large and mostly treeless park. It encompasses the reuse, the razed past, the re-appropriation and the pleasure. You’re here on the tarmac, beer in hand while the sun sets, whether you’re arriving, departing, or somewhere in between.

Kate Brown is a writer and curator based in Berlin. She is the European editor of artnet News and co-directs the non-profit art space Ashley Berlin