Like all great cities, Rio de Janeiro is more than one place. There’s the gringo fantasy: girls in bikinis, sex, hedonism. There’s the white elite: luxury flats, servants, plastic surgery and holidays in Europe. There are the under-paid, under-valued Black women who work in those homes. There are the bohemians of Santa Teresa, up in the hills, living in old European mansions. The sex workers of Copacabana and Vila Mimosa. The all-night parties in Lapa. The sloths, snakes and monkeys in the Tijuca rainforest, overlooked by Christ the Redeemer. All of these Rios exist. There are hundreds more.

Everything is a bit over-the-top: the sun, the humidity, the blue Atlantic, the mountains, the sheer ridiculous beauty, the bawdy funk carioca music blaring from cars; the divisions between rich and poor, black and white. Cariocas drive quickly, walk slowly and talk loudly, in an accent as singular as Scouse or Geordie. One of my earliest memories is of watching a football match on TV. When Brazil scored a goal, the city seemed to shake with joy. Celebratory gunshots rang out from the favela.

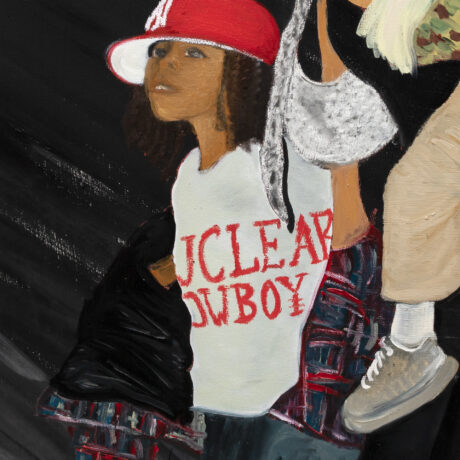

“Like all great cities, Rio is both beautiful and ugly”

Another thing that unites cariocas is the beach—most famously, Copacabana and Ipanema in the wealthy Zona Sul. I’m an Ipanema girl, but let’s not mention the Tom Jobim hit, because he wrote many more interesting songs about Rio. In Samba do Avião he sings from the perspective of someone looking down from a plane, admiring the glittering ocean and endless sand. “Rio,” he sings, “você foi feito pra mim” (“you were made for me”). On the beach, all kinds of cariocas gather to swim, sunbathe and consume endless drinks and snacks; usually Skol beer, cold mate tea and Biscoito Globo (crunchy, light tapioca biscuits), though you can buy almost anything—pastries, açaí, caipirinhas, Lebanese food, bikinis, jewellery—from the comfort of your sarong.

Ipanema leads to Leblon, the most expensive neighbourhood in Latin America, which leads to the Vidigal favela, nestling beneath the Dois Irmãos mountains. Apparently, the view from Vidigal is stupendous. I wouldn’t know, I’ve never been. I left Rio when I was a child, but it isn’t uncommon to spend your entire life in the city, going to the beach, admiring the twinkling lights of Vidigal as the sun comes down, but never venturing into the neighbourhood.

Around 1.5 million people live in Rio’s favelas—about a quarter of the population. Rocinha is the largest, but Cidade de Deus is the most internationally famous, thanks to Fernando Meirelles’ 2002 gangland blockbuster, City of God. It starred several young, Black actors from the neighbourhood, and turned its white, middle-class director into a star. A couple of years ago, the film’s lead actor, Alexandre Rodrigues, was working as an Uber driver. Some of his co-stars were far less fortunate. Like all great cities, Rio is both beautiful and ugly.

Luiza Sauma was born in Rio and lives in London. Her novel Flesh and Bone and Water is set in the two cities