Elephant and Artsy have come together to present This Artwork Changed My Life, a creative collaboration that shares the stories of life-changing encounters with art. A new piece will be published every two weeks on both Elephant and Artsy. Together, our publications want to celebrate the personal and transformative power of art.

Out today on Artsy is Wabwire Joseph Ian on Aïda Muluneh’s Knowing the Way to Tomorrow.

For me, the choice was straightforward; it was the aftermath that hurt. I was completely ill equipped to deal with the physical disconnection that followed an abortion in my early twenties. Just graduated, in a newish relationship and living paycheck to paycheck, I was certain this was not the right time to have a child. I saw it as a practical, medical procedure I was undergoing that had nothing to do with my emotions, and desperately wanted it to stay that way. It was only in the months and years that followed that I was hit with a paralysing hatred towards my own sexuality, which seemed both irrational and inescapable.

Abortion should always be a personal choice. It is something many only tell a few people about, and it is obscured by shame and secrecy in public discourse. Despite this, the reality of termination is far from private. It begins with the protesters who crowd outside the clinics. Walking alone through a dense group of them on day one was the first time I felt scared and vulnerable about something which, up to that point, only my partner and doctor knew about.

Leaving the surgery on the second day, I felt as though I was overdosing. In the carpark, dripping in cold sweat and overcome by nausea, the only thing I could think to do was lie down on the pavement and breathe heavily as people walked past my outstretched feet. My partner eventually coaxed me up, and we headed home for a painful and melancholy evening.

I was working as a model at the time, and two days later I had fittings booked for a regular client. I needed the money and was embarrassed to tell my agency what had happened. So with the effects of the procedure far from over, I found myself squeezing into a pair of skin-tight white jeans to walk up and down in front of a buyer. As soon as I left, I got a call from my agent. I had put on weight and the rest of my dates had been cancelled. I didn’t say what had happened, just mumbled that I was sorry and desperately promised that I’d lose the weight soon.

In the end, I lost over two months’ rent. I found myself furious at my body: for ruining a job I had worked tirelessly to maintain, for placing me in a precarious financial situation, and for having a function that meant I was the one accepting the consequences for two of us. Compounding this, I didn’t feel I had the right to feel anything, as it was a choice I made for myself.

Over the next few years, it only felt more complicated. No matter how much I reminded myself that I didn’t judge other people who had gone through this, I couldn’t reconnect. I was numb and unresponsive, as though my flesh had no nerves running through it anymore. I spoke to a therapist who suggested that it is possible to for the physical and psychological processing of grief and trauma to be misaligned. I felt as though my body was on its own path, one which I didn’t understand and couldn’t access. The more I tried to reason with it, to make it want physical closeness, to get over it and feel powerful again, the more shut off it became.

“I was numb and unresponsive, as though my flesh had no nerves running through it anymore”

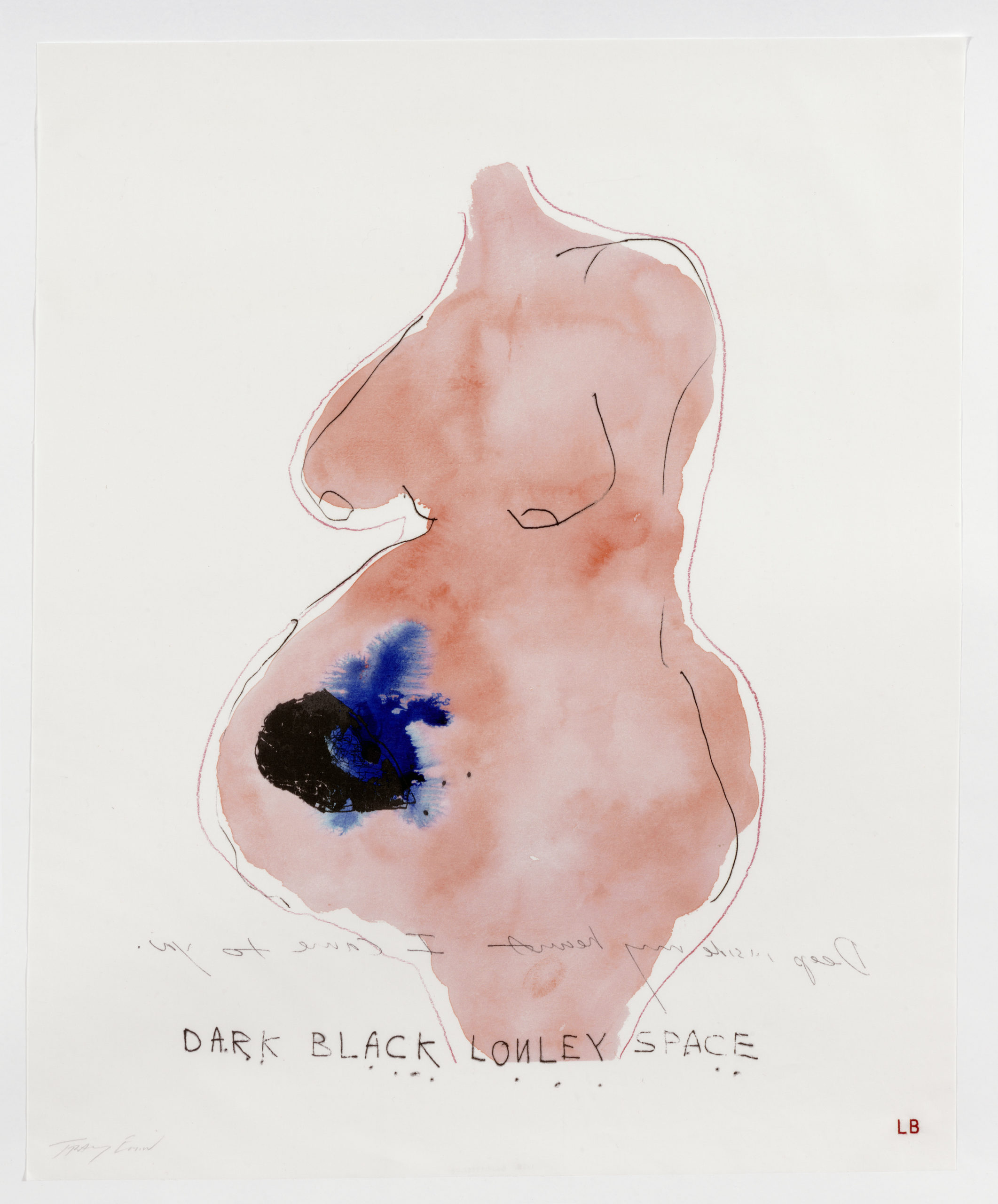

I visited White Cube’s all-women, surrealism-inspired Dreamers Awake in 2017, and amidst the array of works on show by artists such as Sarah Lucas, Mona Hatoum and Kelly Akashi, I found myself glued to Deep Inside My Heart (2009–10), a collaborative piece by Tracey Emin and Louise Bourgeois. The painting shows a female torso with a big blotch of midnight blue ink sitting heavy in the womb area, and thin tendrils bleeding out into the mass of stomach that surrounds it. “Dark Black Lonely Space” reads the text underneath, in Emin’s distinctive, spidery handwriting. The woman depicted in this work doesn’t have a head. She doesn’t have arms or legs. She is a pair of breasts, a swollen stomach area and a painful, gaping void.

Seeing these strong and highly sensitive artists come together—one who has been vocal about her own abortions and one who made many works about motherhood—gave me the opportunity to accept this as a loss for the first time, and one I didn’t necessarily need to understand intellectually. It is unclear whether this image is about abortion, miscarriage or infertility; the inky marks connect purely with the feeling of hurt and emptiness within this part of the body. The supposed “choice” of the woman in this work is not important, nor is her personal situation. This piece moves beyond the political and focuses inwards. In this internal world, pain is pain and loss is loss. It doesn’t need to make sense, and she doesn’t “deserve” to feel or not feel anything.

I was also moved by the dignity of her presentation, something that had felt missing throughout the whole experience for me. She appears to be totally alone in her own space. Her naked body, bloodied on the inside, doesn’t look as though it is carrying shame. It was one of the first artworks I ever really engaged with that connected with abortion, and seeing this gut-wrenching yet somehow serene piece hanging in White Cube normalised the subject for me.

I thought of how many people feel this dark ache snaking through their bodies, a confusing mix of guilt, detachment and internalised stigma, with little to see for it on the outside. The work made me feel held and seen, as though I could let go for a moment and just let it wash over me. This wasn’t a riddle to work out, or a feeling to fight against; I was going through an intense physical reaction, and it was alright to sit with it for a while.

“I thought of how many people feel this dark ache snaking through their bodies, a confusing mix of guilt, detachment and internalised stigma”

As I looked at the work again and again in the weeks that followed, I realised that I had never connected to my body as that of a complex woman, one that had possibilities aside from pornographic sexuality. I hadn’t felt worthy of the kind of sensitive, adult body painted by Emin and Bourgeois, and as I witnessed this depth within my own physicality, I had no idea how to relate to it. I acknowledged how much social pressure, embarrassment and judgement I had absorbed from outside of myself during my teens and early twenties. I saw that this event had been the final straw in long feeling that my desires led to damaging places. Sex was unavoidably tainted.

Emin has been one of the principal artist voices on abortion and female sexuality, and the stigma that surrounds it, fearlessly putting her own story out there and no doubt helping many others in the process. In 2009 she wrote about how she felt viewing one of her exhibitions as a successful artist: “My mind was thrown back to 1990, coming round from the anesthetic after having my abortion, and that overwhelming sense of failure, failure as a human being and failure as an artist.”

Both Emin and Bourgeois depict pain in a visceral way, evoking deep and internalised traumas. They both remove the female body from societal expectations of purity or projected, palatable sexuality and embrace it in all its messiness. Each artist centres the subject in their own way; their work is political, but the viewer is invited to engage with an intuitive, personal narrative, rather than an academic debate.

It can be difficult to see something that is so polarized in public opinion as being full of emotional grey areas. Amongst those I know who have had terminations, no one has had the same experience. Some hate to see it dramatised and others want much more sensitivity around the subject. I will be forever grateful to have lived in a country where a safe and legal procedure was an option at that time, and I know my position is a privileged one.

As destabilising as this period in my life was, if I were to go back and make the choice again, I would do the same. That doesn’t change the fact that it shifted something massive in my body, conscience and understanding of myself as a woman. Perhaps I won’t ever fully heal from something that had such a hefty impact on me as a young adult, but this work opened up a space of acceptance and reconnection, and I return to it often.

Did an artwork change your life?

Artsy and Elephant are looking for new and experienced writers alike to share their own essays about one specific work of art that had a personal impact. If you’d like to contribute, send a 100-word synopsis of your story to office@elephant.art with the subject line “This Artwork Changed My Life.”

Head to Artsy to read their latest story in the series, a piece on Aïda Muluneh’s Knowing the Way to Tomorrow

READ NOW