The chance of befriending your Uber driver––for any reason other than the mutual desire for a five-star rating––isn’t overly likely for most people, and it is even less likely to lead to a collaborative piece of responsive installation art. But that was the case for Miranda July, the creative polymath (she counts filmmaker, actor, author and artist among her occupations) who struck up a conversation with Oumarou Idrissa during a drive to Malibu, where she was due to interview Rihanna. To her surprise, Idrissa had met the singer too, and after he provided photographic proof, they discussed their mutual fandom. “We talked about her, but we also talked about him and his life story,” she tells me over the phone from Los Angeles. “We both felt really excited; as if we were about to be Rihanna’s best friend, but in fact, we ended up being friends with each other instead.”

“We both felt really excited; as if we were about to be Rihanna’s best friend, but in fact, we ended up being friends with each other instead”

After their chance encounter, the pair kept in contact and July came to know more and more about Idrissa’s former life in Niger; his struggle as an illegal immigrant following problems with his student visa; and his subsequent US citizenship. During his undocumented stay he lived in constant fear of being discovered, which has left him plagued with perpetual anxiety and insomnia. As July puts it, “It’s like any kind of PTSD that lives with you [long term]. I think we can all relate to the things that haunt us and keep us awake. Those things that prevent us from being able to let go and relax.”

At one point, Idrissa’s precarious living situation led to a house-sharing arrangement with July. She offered him the use of her studio from 5pm to 9am, while she maintained her daytime working schedule. “It’s not like he was living with me and I was thinking ‘How could I make art out of this?’” she assures me. “It was a relationship with all of the ups and downs. We fought sometimes; it wasn’t perfect in and of itself.” Whether or not it was planned, their atypical friendship ended up being the resolution to nascent ideas for a project commissioned by the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London as part of The Future Starts Here, a major new exhibition exploring high-tech innovation. July began investigating the technology behind “smart curtains”, a catch-all terms for automated drapes that are controlled by smartphone apps, voice control or sensor systems.

“I had this idea that real people could trigger smart curtains and create a different meaning than they were engineered for,” she explains. “For a long while, I thought they would be activated by people in London because the piece is about real time, but I thought that was too far away if something went wrong.” In her quest for someone closer to her LA home, she was faced with the fact that most participants would be asleep when the show was open. Idrissa was the exception. “We’d already talked a lot about his insomnia and I realized that this was a way for me to understand his experience and convey how [emotionally] everything doesn’t just end up clean and tidy once you have citizenship.”

The resulting installation features four pairs of luxurious velvet curtains in different colours, which are activated by Idrissa’s activity, obtained through a range of data capture devices. His sleep cycle is represented in blue; his WhatsApp usage in brown; Instagram in green and Uber activation in pink. For July, there are some instant similarities. “To see the recognizable movement of waking up and checking Instagram right away, on a physical level that’s such a familiar action to me.” But she is also under no illusion that their lives share anything more than a passing resemblance. For one, he still suffers from an overwhelming sense of isolation. In the explanatory text that accompanies the installation he states simply: “I don’t have any close friends in America, so my phone is my everything.” He exchanges messages and photos with his twenty-one siblings every evening and used to speak to his mother nightly, before she passed away two years ago.

The idea of constant surveillance, however well-meaning, is somewhat unsettling, so it seemed impossible not ask July about her ethical concerns around the piece, not to mention Idrissa’s initial response to the prospect of such an unorthodox collaboration. July assures me he was extremely enthusiastic. “The truth is that Oumarou wants his story told any which way it can be. He’d be psyched if I was also writing a book and making a movie about him. He said that is why he told me his story on the way to meet Rihanna, he was like, ‘Ok well, why don’t you interview me too,’ so that is part of his interest.” July also stresses that the piece can run on a pre-programmed script, so he does not have to worry about constantly performing or trying to stay awake. If anything, Idrissa is the one pushing for authenticity. “He gets it, but he says, ‘It’s so much better when it’s live! That’s how everything is these days!’”

This notion of compiling data in what July refers to as an “emotional portrait” serves as something of an antidote to the covert processes used by social media and third-party apps to form consumer profiles of their users. It’s a pertinent subject, especially considering that many of us have signed away our privacy rights without really understanding the risks. Idrissa’s active participation moves a step beyond this quotidian compliance and instead serves as a vehicle for him to tell his personal story, albeit in an abstract, yet strangely intimate manner.

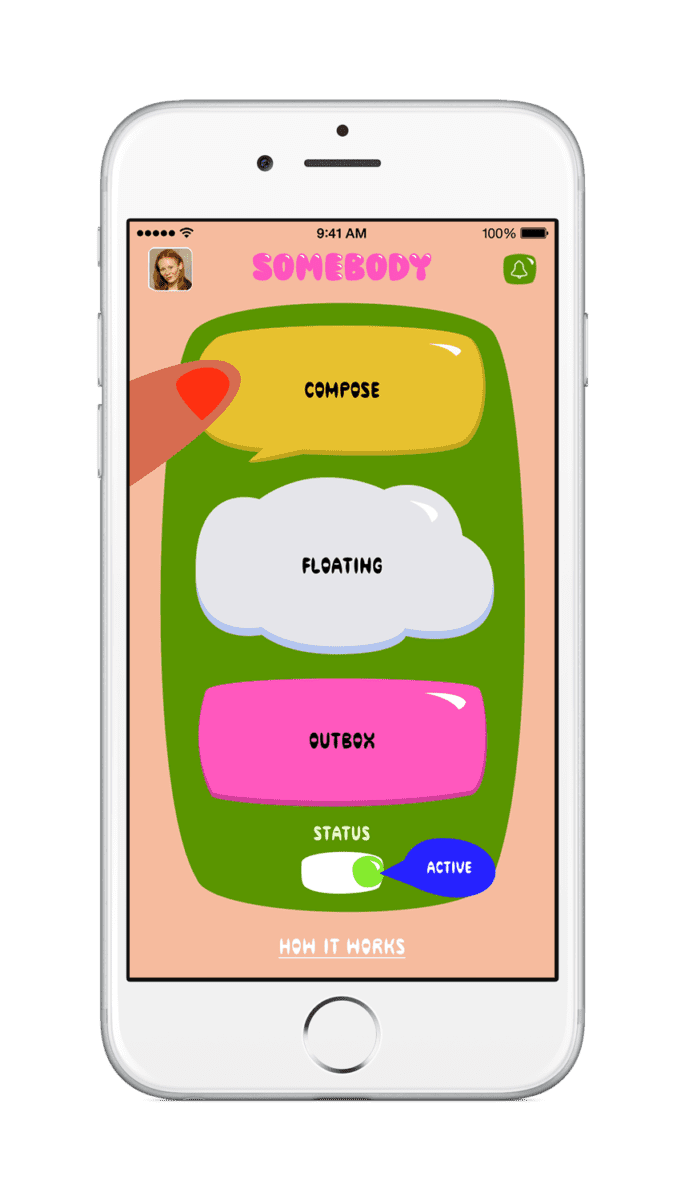

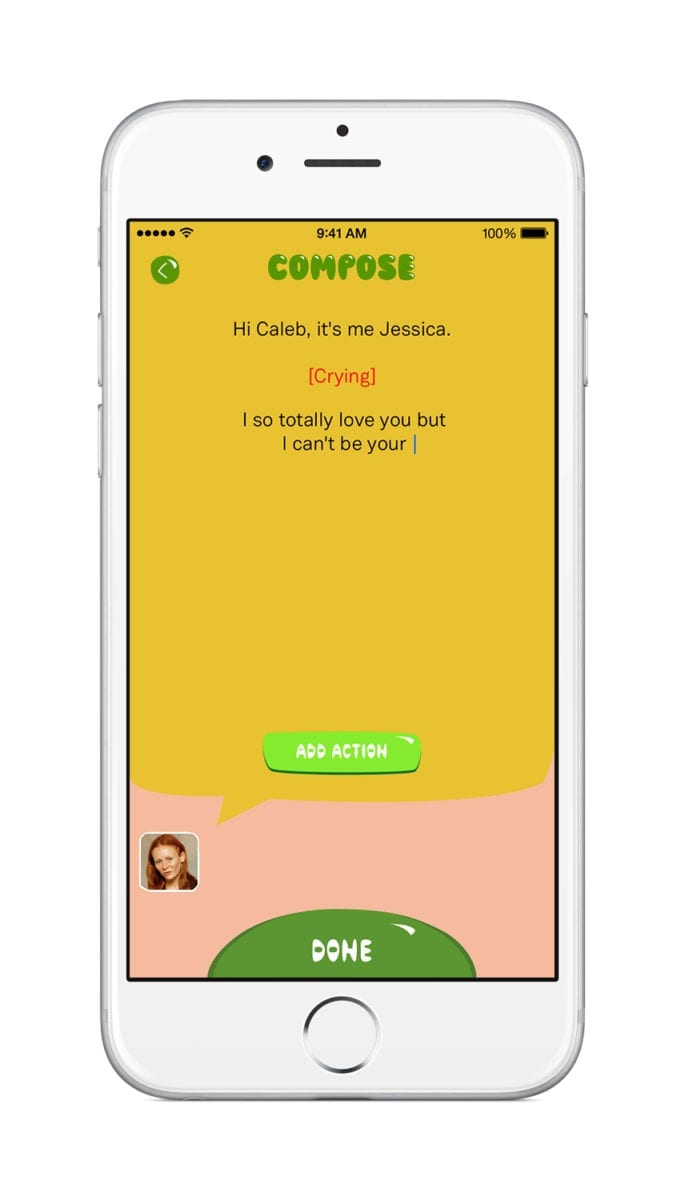

- Somebody, 2014. App

This commission is certainly not the first time that July has investigated unorthodox modes of communication in her practice. For instance, her short-lived app Somebody

straddled the worlds of messaging and performance art by inviting individuals to send notes through the interface, which would be relayed to another user who was near the desired recipient at that point in time. They would then operate as a “stand in” for the author, thus creating a strange triangular system that connects virtual and IRL communication. Her interactive sculpture series 11 Heavy Things

also relies on human interaction in order to be activated. These simple, white structures incorporate specific messages that invite onlookers to embody them through basic actions, such as sticking a finger through a hole or standing on a plinth.

Over a decade ago July also wryly encapsulated the shortcomings of early Internet communication in her 2005 feature film Me, You and Everyone We Know. In one of multiple plots, a middle-aged woman is horrified to discover that she has been conducting a chat-room romance with a young boy, after being seduced by his seemingly kinky obsession with “poop”. His creative use of a bespoke emoticon ))><(( otherwise known as the “back and forth” gained cult status among fans.

It is hard not to be nostalgic when thinking about these archaic forms of online interaction, back when dial-up and desktop sites reigned supreme. It seems a world away from our powerful, all-knowing smartphones and an almost incessant need to digest global information. Given the futuristic premise of the V&A show, I tentatively ask July whether her installation also approaches concerns around frenetic millennial phone usage and the anxiety it can induce, but it’s not an interpretation that she strongly aligns with. “It’s easy for that conversation to become about guilt; a sort of a self-obsession concept. “I have to get off my phone because I’m so important.” The assumption that your phone isn’t something vital is a privileged presumption because it assumes that you get to be close to everything that matters to you. Oumarou explained that before smartphones you had to rely on very expensive charge cards, but he spent that money because he would do everything possible to stay connected to his family.”

This cements the point that this work of art is, rather critically, about Idrissa as an individual. His friendship with July is authentic, and any opinion to the contrary is disproved when he calls her for a catch up during our phone conversation: “Oh my god, he’s calling right now––that’s so weird!” He also had his moment in the spotlight during a testing exercise over in LA. “Everyone was star-struck by him,” July says, with an air of pride. “He’s extremely well-dressed and very tall, with a real presence. He enjoyed getting to be a part of the piece in person, because he won’t get to see it when it’s running.”

In the same vein, there’s one final question I have to ask concerning the work’s title: I’m the President, Baby. Where does it come from? Apparently, it is a direct quote from Idrissa’s Instagram, dated 10 November 2016, two days after the presidential election result. Again, it relates to their friendship. “Our relationship overlapped in this very pointed way because he was registered to vote at my house, and it was so meaningful for him to participate. I was sort of nervous; I couldn’t imagine he was voting for Trump, but at that point people were doing weird things. So, I said, ‘Do you know who you’re voting for?’ and he replied ‘Oh, I’m with her,’ and I loved that, especially as not a lot of men in my life were saying it at that point.” The title also anchors the piece in time, a concept July was eager to communicate. “It isn’t just any immigrant story, at any time––it’s now.”

This feature originally appeared in issue 35

BUY ISSUE 35