Elephant and Artsy have come together to present This Artwork Changed My Life, a creative collaboration that shares the stories of life-changing encounters with art. A new piece will be published every two weeks on both Elephant and Artsy. Together, our publications want to celebrate the personal and transformative power of art.

Out today on Artsy is Casey Lesser on Pablo Picasso’s Guernica.

I grew up mixed-race in a suburb of Seattle, born to two immigrants who wanted nothing more than for me to be an American in the most abstract sense of the term. Whiteness was the default, and often felt like the goal. Still, the day-to-day inconveniences of racism are as evident now as they were then. I move train carriages when I’ve been told, through words and through actions, that people like me have no place in spaces like these; I’ve left jobs where I was made to feel like tolerating racism was part of my quarterly performance goals.

When I walk into a room and made to feel unwelcome, I wonder why I am there, and leave if no clear objective materializes. It would be wonderful, I think as I enter an all-white space, to not have to consider whether the sour look on someone’s face is because they now have to watch their words around me. When I try to explain the tiny psychic costs of worrying what my presence might mean, many people plead, “Why must everything be about race?” I couldn’t agree with them more. Why must everything be about race?

I can’t imagine a world without racism; instead, I picture one where racism is less insidious and widespread. In the same way, it is easier to talk about the history of art with fewer male artists than it is to remove their presence altogether. Rather than erase them, the focus can be turned to their female counterparts. My university professor in Seattle offered a class on just this, constructing a recent history of the arts while circumnavigating the legacies of men. In our classroom, Krasner was more important than Pollock; the lectures focused on Ana Mendieta, not Carl Andre. We covered Louise Bourgeois, Jenny Holzer, Yoko Ono

and, most importantly for me, Adrian Piper.

“Whiteness was the default, and often felt like the goal. Still, the day-to-day inconveniences of racism are as evident now as they were then”

It was Piper’s work that taught me to ask the questions that I want answered, rather than to answer questions that should never have been asked. Born into a mixed-race family in 1948 and privately educated from high school through university in New York City, Piper was also accustomed to existing in majority-white spaces from an early age. These spaces are ruled by specific codes of conduct, many unspoken and often unquestioned. In her early series of performances, Piper began to explore what existed beyond their limits.

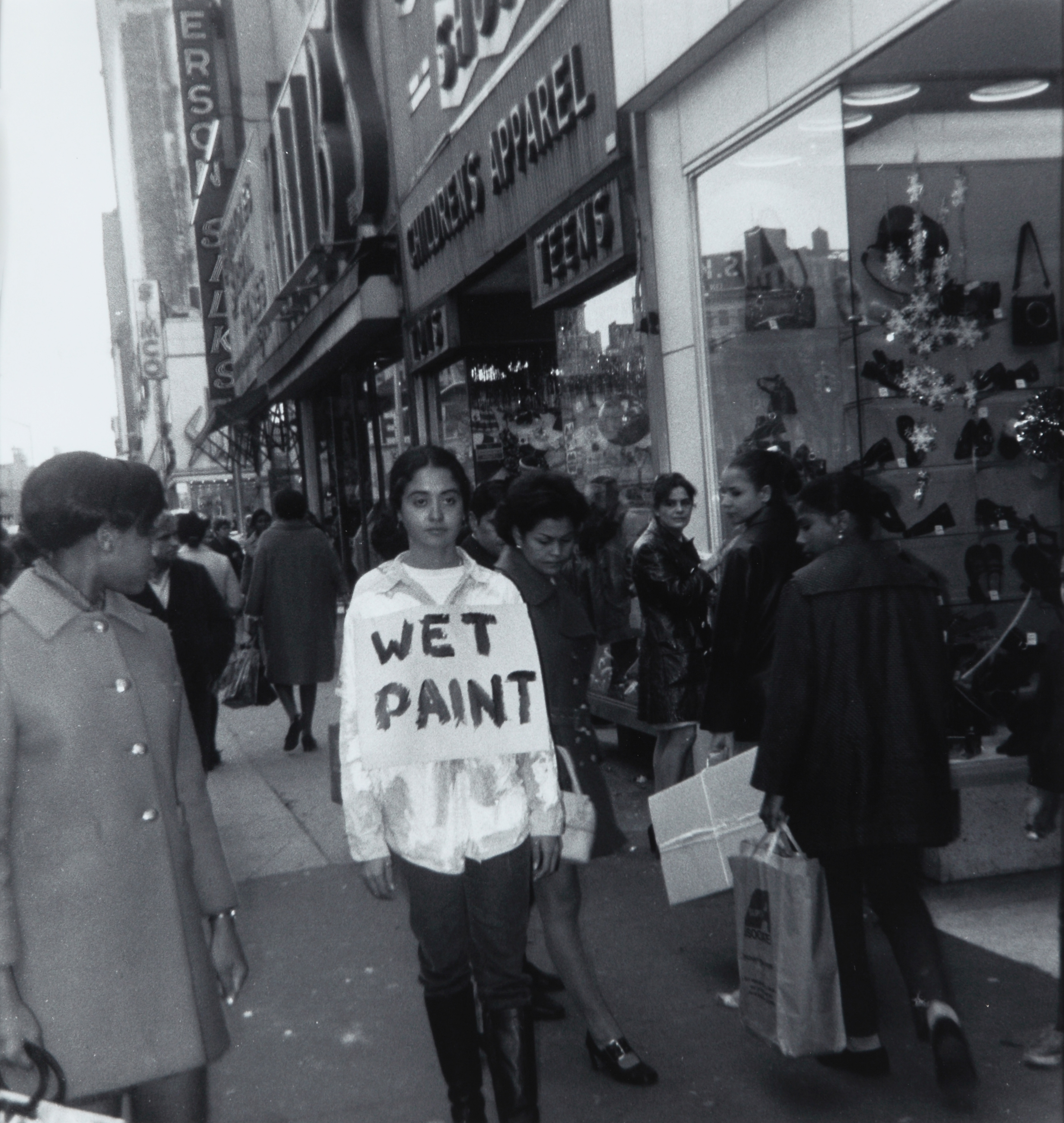

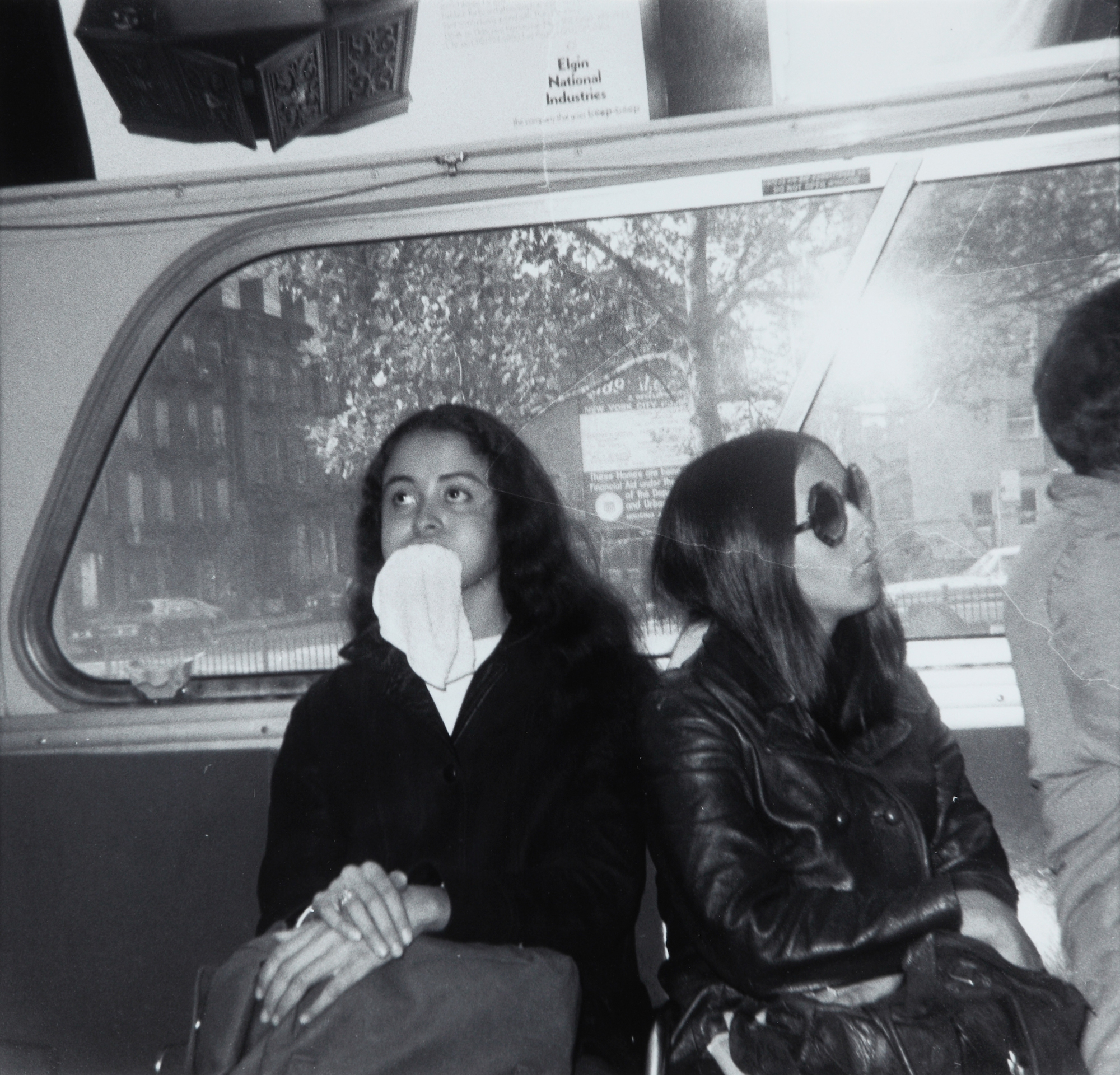

She called these performances, staged during the early 1970s, Catalysis, after her ability to “catalyse” or affect audiences. In one, she caught the D Train during the New York rush hour in a coat carefully marinated in eggs, vinegar, fish oil and milk. In another, she went shopping at Macy’s dripping in white paint and wearing a sign that read “WET PAINT”. She filled her purse with ketchup and fished out a comb, a mirror or loose change while on the bus and in public restrooms. She shoved towels into her mouth and stared back at people on the street, her face bulging with excess.

Her interventions were out of the ordinary, but they also proved how lenient a working definition of the ordinary could be. When she asked someone on a subway platform for the time, they gave it to her. “You know you are in control, that you are a force acting on things, and it distorts your perception,” she said in an interview with Lucy Lippard in 1972. “The question is whether there is anything left to external devices or chance. How are people when you’re not there?”

I have often wondered what others say when I’m not in a room. It’s not because I care what they think (although I do), but because I want to know what my presence precludes and what my absence cultivates. It would be optimistic to think that when I’m not in a room, people are filled with a desire for me to be there, or to imagine that they give much thought to the conditions that have kept me from being there. It’s more realistic to assume that many are, in fact, relieved by my absence.

It is true that I can be an unforgiving sparring partner in disputes. My experiences of race and racism are non-negotiable, and my patience for simple questions that require complicated answers is limited. I do not care what your racist family members said over dinner, and I will loudly tell you so in polite company. In majority-white spaces, I have been introduced with a disclaimer, like a bathroom door that won’t lock or a dog that bites. I no longer make a habit of fitting in with others who will not go out of their way to accommodate me. Increasingly, I refuse to make myself convenient.

I’m still unpacking the collateral damage of whiteness. When I first discovered Piper’s work as a university student in Seattle, I was still working through the independence of adulthood. I could question how structures and systems like whiteness had formed my perspective; I could try to unpack its effects on my work and myself. I began to reconcile whiteness as a condition for success and whiteness as a system in which I had to work. My body was policed, I realised, but that didn’t mean it had to be political.

“Covered in ketchup or wet paint, Piper and her body weren’t convenient—they were as much of a contradiction and a logical inconvenience as they were an obscenity”

When asked if she found that the power of the Catalysis series had to do with her being a woman and being black, Piper said, “As far as the work goes, I feel it is completely apolitical. But I do think that the work is a product of me as an individual, and the fact that I am a woman surely has a lot to do with it”. She continued: “You know, here I am, or was, ‘violating my body’; I was making it public. I was turning myself into an object”.

Covered in ketchup or wet paint, Piper and her body weren’t convenient—they were as much of a contradiction and a logical inconvenience as they were an obscenity. But for the people with whom she interacted, Piper and her body became a new benchmark—a metric of what could exist within their understanding of ordinary.

The better part of a decade has passed since I was introduced to Piper’s work. I’ve moved countries and continents. I’ve grown older, maybe smarter, but mostly more tired. People still pull faces when I enter the room, and I still wonder quietly wonder if my body is repulsive, as Piper’s was when soaked in cod oil or smeared in ketchup. Racism is still a day-to-day inconvenience. But, like Piper, I now know that I can be one too.

Did an artwork change your life?

Artsy and Elephant are looking for new and experienced writers alike to share their own essays about one specific work of art that had a personal impact. If you’d like to contribute, send a 100-word synopsis of your story to office@elephant.art with the subject line “This Artwork Changed My Life”.

Head to Artsy to read their latest story in the series, a piece on Pablo Picasso’s Guernica by Casey Lesser

READ NOW