It started in China in 1982. When the US artist Robert Rauschenberg was in Jingxian for an extraordinary residency as the country began opening up to the West, he fell into conversation with a Chinese cook. What Rauschenberg learned that day sowed the seeds for an ambitious project, even by the artist’s high standards. Called the Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange or ROCI—pronounced “Rocky” after the artist’s pet turtle—the project exemplified the Rauschenberg genius for creating art anywhere out of anything. His can-do spirit, and belief that art has the power to overcome geo-political divisions and foster peace, seems more relevant than ever as an increasingly polarised world emerges from lockdown.

The highlight of Rauschenberg’s first visit to China was due to be a working trip to the Xuan paper mill, said to be the oldest in the world, for a project initiated by the Los Angeles print studio Gemini G.E.L. Despite permission from Beijing the artist and his team hit a roadblock. Suspicious local officials feared the Americans would steal their paper making secrets. One excuse was that the workers were nude when they stood in the vats of paper pulp (the irony was not lost on the bisexual artist). Barred from the mill, Rauschenberg had to send instructions to the craftsman.

One day while “quarantined” in a VIP compound, the artist got talking to the chef and discovered he had not seen his family for years, although they lived only 20 miles away. Travel required special permission for the Chinese, not just foreigners. “Bob started thinking at that point that if these people didn’t know what was going on 20 miles away, they certainly didn’t know what was going on 2,000 or 10,000 miles away,” recalled his assistant, Donald Staff, who went on to coordinate ROCI.

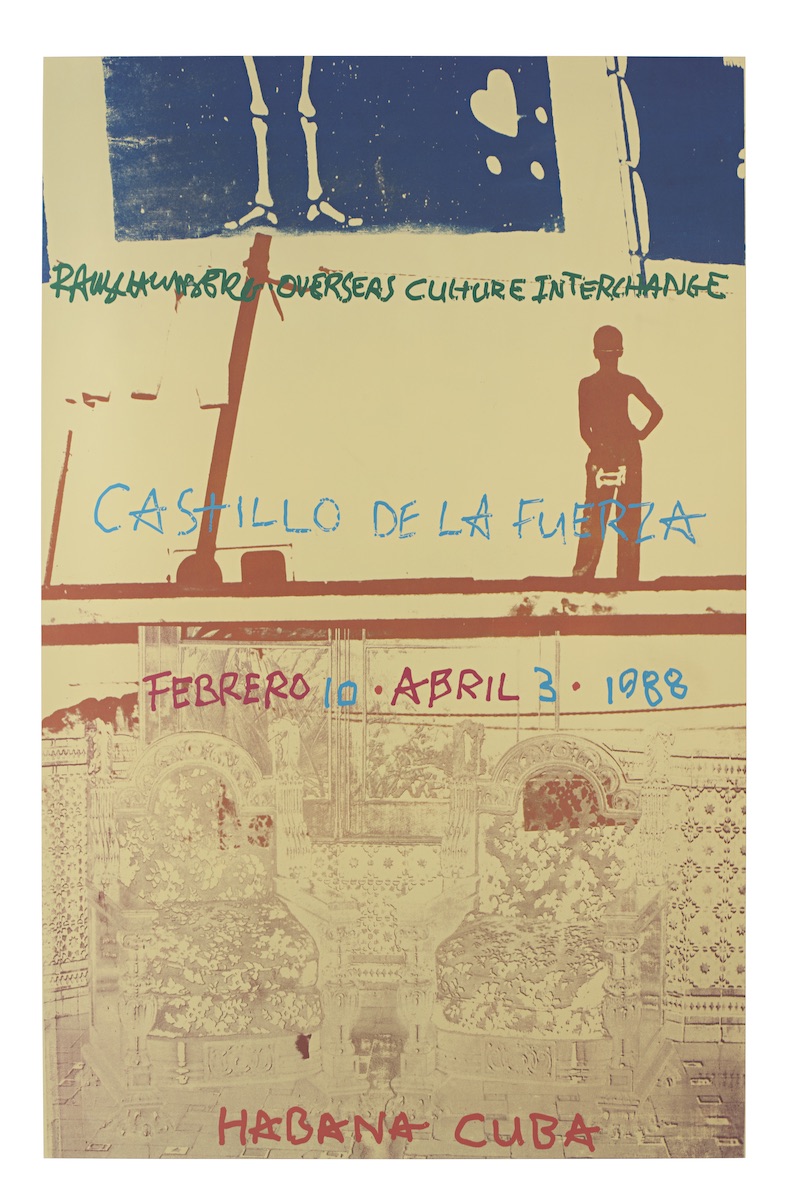

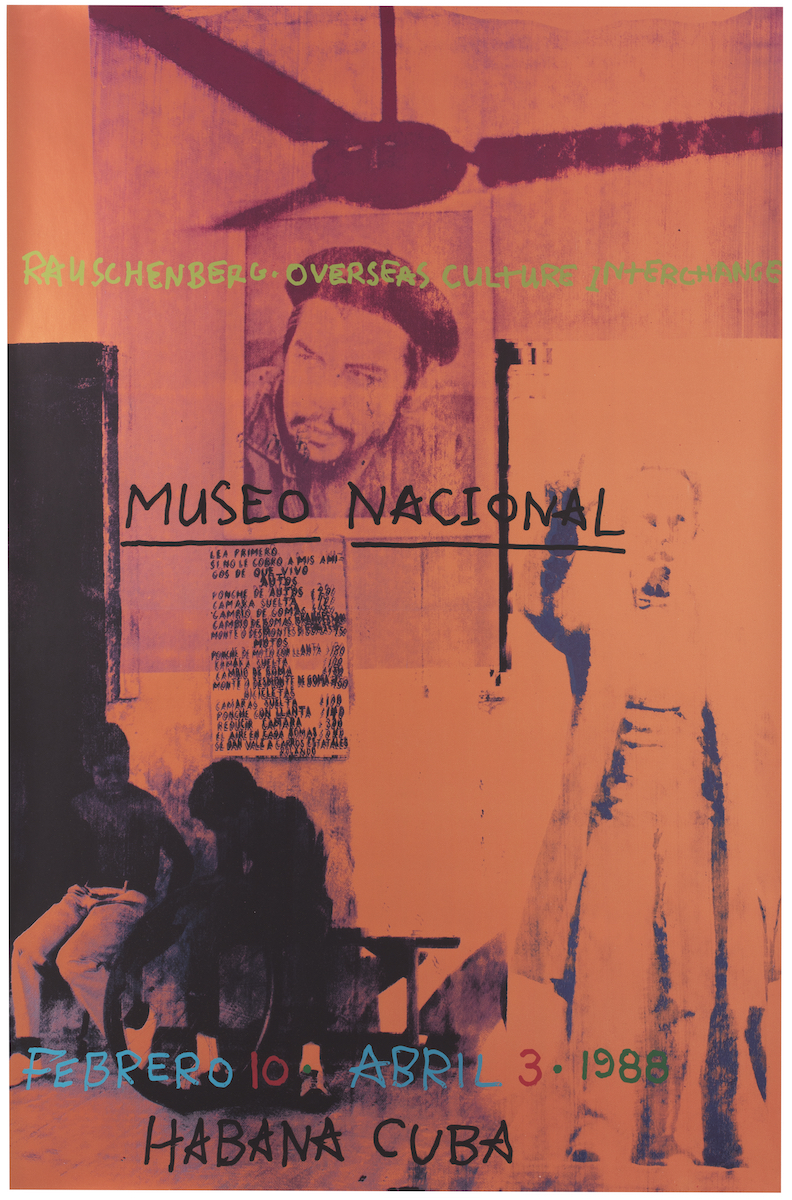

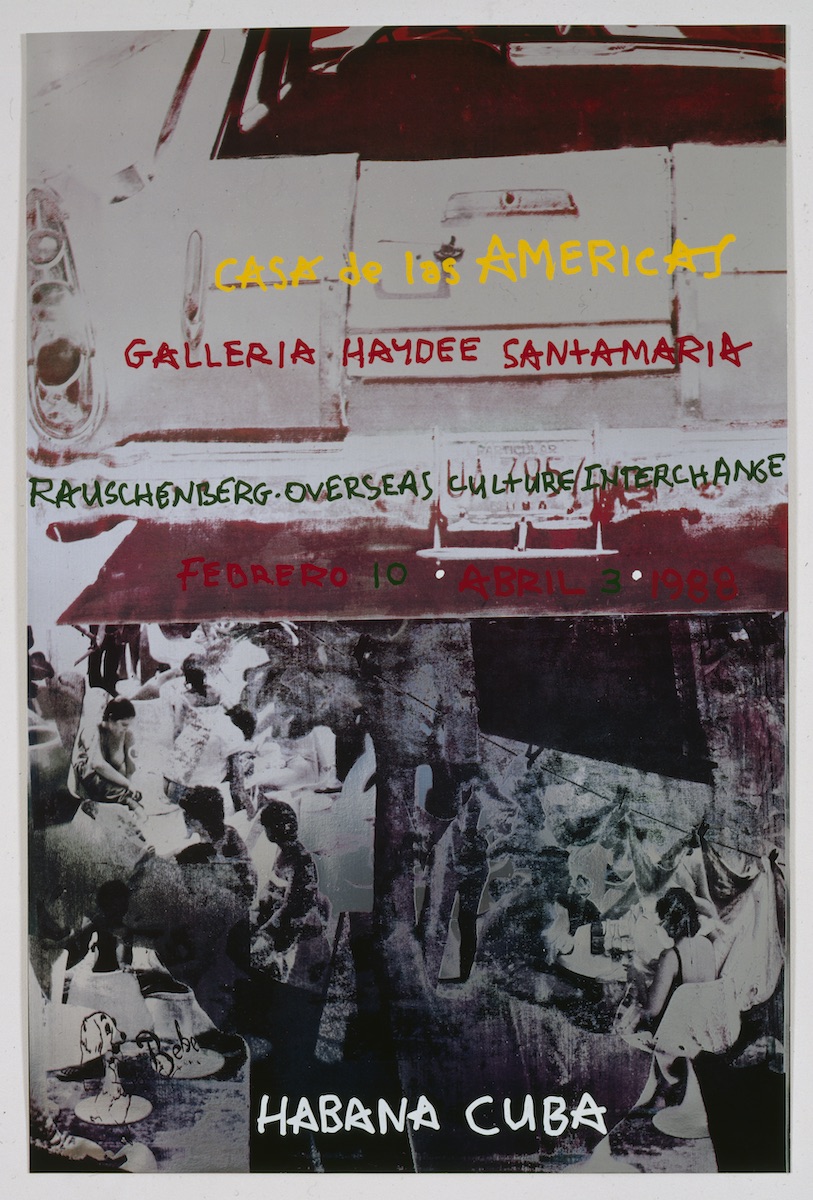

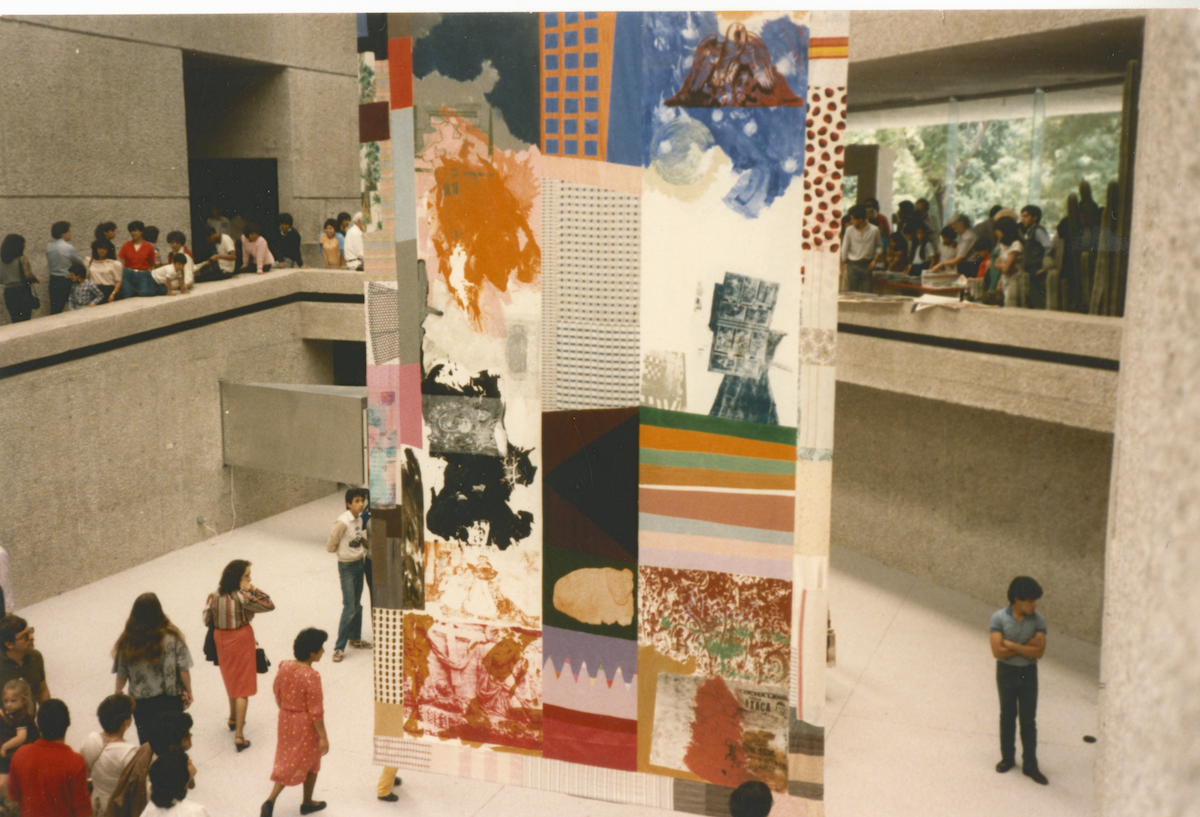

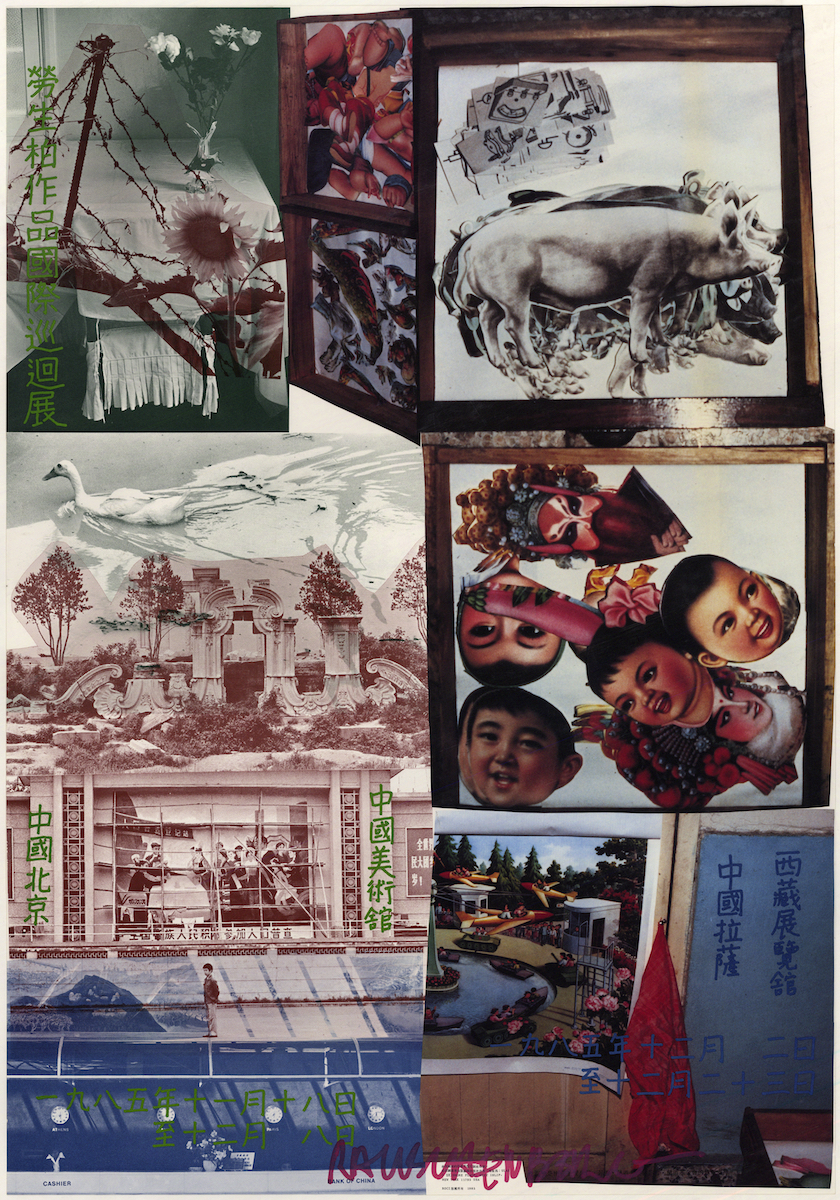

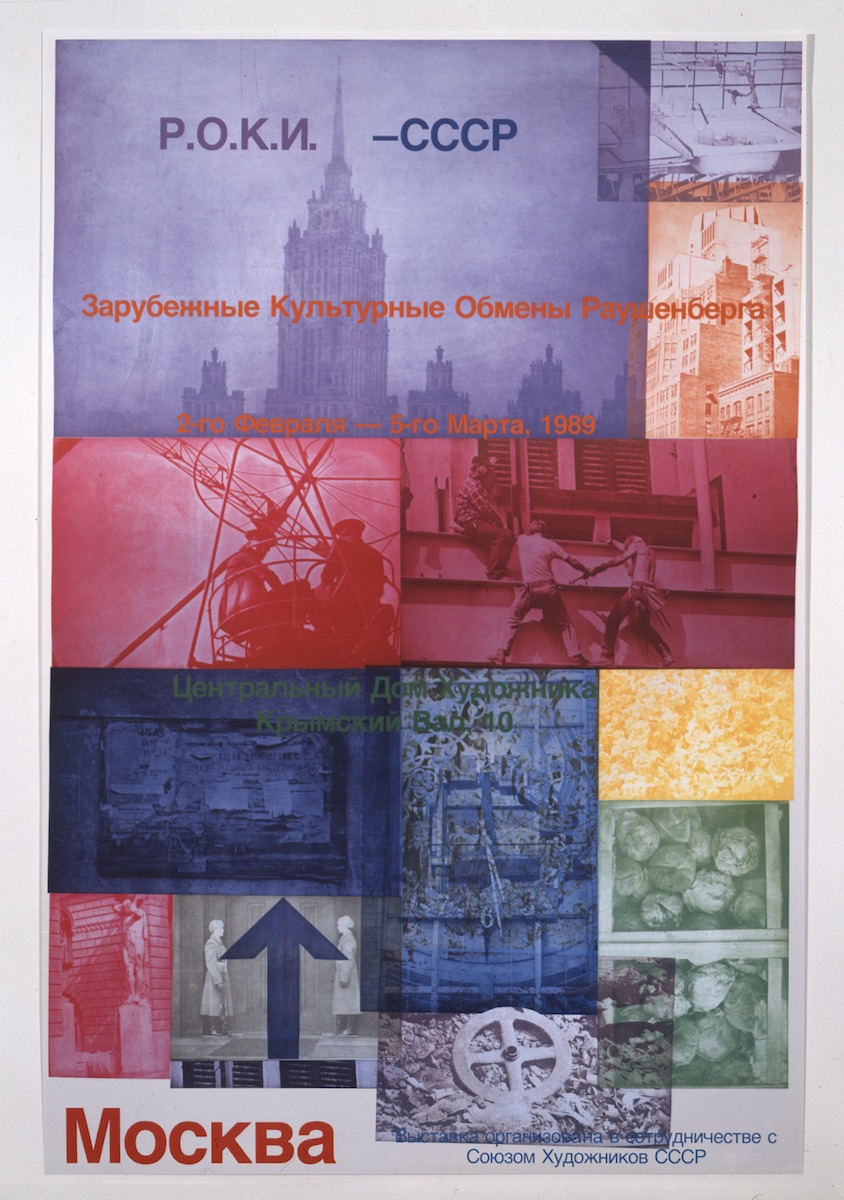

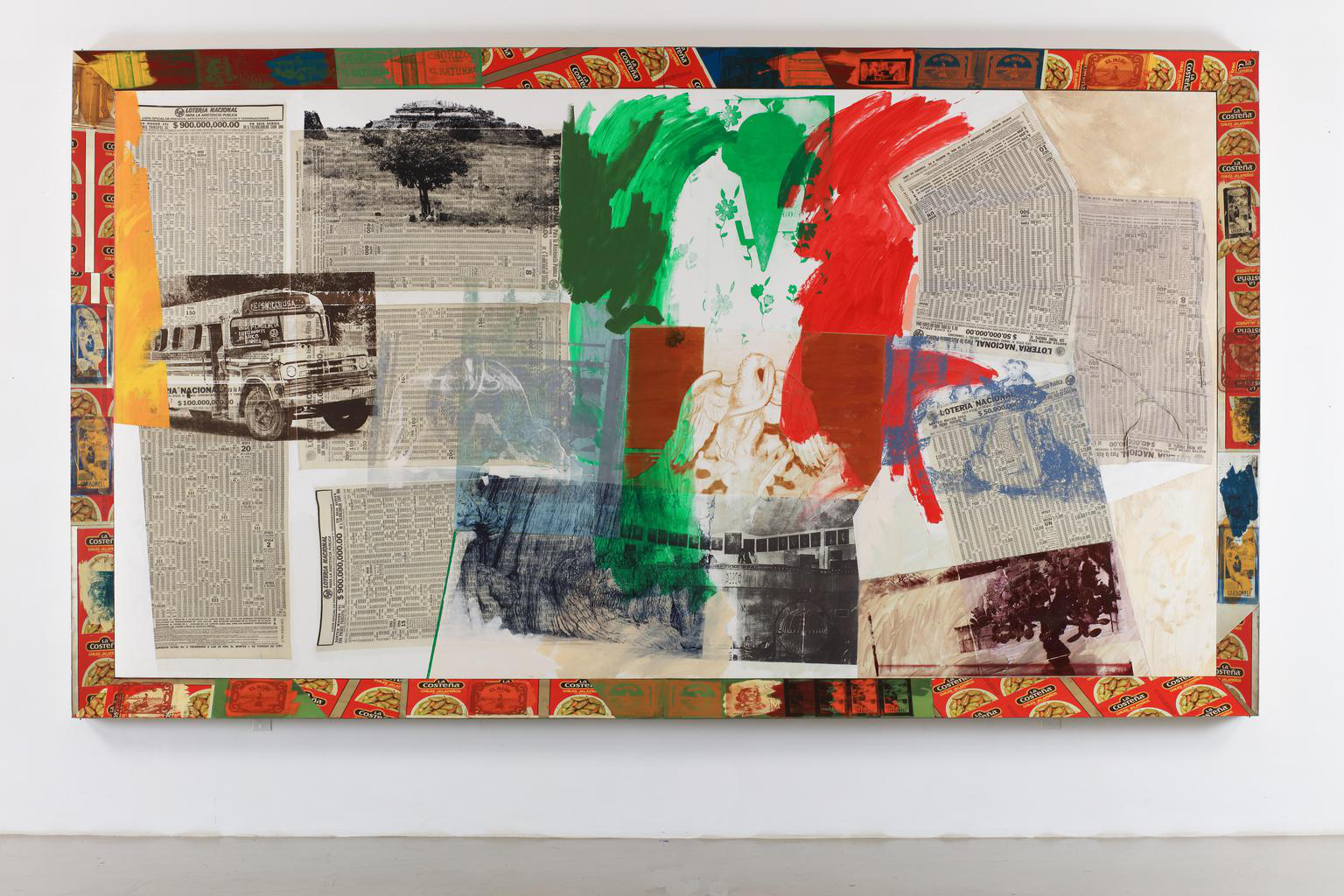

The subsequent series of large-scale, politically-engaged exhibitions travelled to ten countries and was seen by more than two million people around the world from 1984 until 1991. Rauschenberg sought out political hotspots, with Castro’s Cuba and General Pinochet’s Chile among the most controversial venues. Venezuela was tricky, then as now. The artist typically made the works featured using locally sourced materials and images, while in 1984 ROCI China included pieces produced in collaboration with the Xuan mill papermakers. It was the first solo show by a western artist allowed by the Chinese Communist Party. It made a huge impact, drawing 300,000 visitors in its three-week run, and influencing a whole generation of contemporary Chinese artists.

The ten-country tour, which culminated in a show at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, generated 125 works of art, which at the time Rauschenberg refused to sell. He would donate one in each country, intending it for a public museum. ROCI also resulted in some of the worst reviews of his career; he was accused of American imperialism and self-aggrandisement, but carried on undeterred.

“It was a ‘slightly naive but well-intentioned approach to activism’”

“A number of countries he scouted around the world did not have the adequate infrastructure to host the exhibition,” says David White, the artist’s curator from the 1980s, who is now the senior curator of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, “though this was of little concern to Rauschenberg himself”. For ROCI Sri Lanka, for example, he proposed works strapped to elephants that would parade through the main streets.

“He even preferred this idea for its dynamism, and the possibility of swapping out the works on a daily basis, so that the event would continually metamorphose,” White says, adding, “Sadly, the more prudent members of his team vetoed the idea.” Sri Lanka, like Saudi Arabia and Senegal, were among the countries on the ROCI bucket list that never took place.

Rauschenberg’s gallerists were aghast. Ilena Sonnabend called ROCI “professional artistic suicide,” and Leo Castelli reportedly held back payments for the artist’s work to try to stop the money going to fund the project. Remarkably, ROCI was largely self-financed by Rauschenberg, who rejected official funding from host countries, and soon realised that corporate sponsorship—be it from tobacco companies or businesses linked to the arms trade—would compromise the project. To keep the show on the road (it cost an estimated $11 million in total) he sold his art. And when the proceeds from his own work, plus an early Jasper Johns, Alley Oop (1958), and Warhol’s Dick Tracey (1960) were insufficient, he mortgaged his homes and studio in Captiva, Florida.

It was a “slightly naive but well-intentioned approach to activism: to bypass political hostilities between these particular countries and the US, and connect with artists on the level of shared interests in making and process,” says Catherine Wood, Tate’s Curator of Contemporary Art and Performance.

She says that ROCI was a culmination of a collaborative way of working that can be traced back to Rauschenberg’s time at the multidisciplinary Black Mountain College, the American off-shoot of the Bauhaus art school. Another formative experience was working as a set and costume designer on the Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s world tour of 1964. It was a “good out-of-town rehearsal for ROCI,” the artist once said.

“Rauschenberg used the form of the exhibition as a means to infiltrate and subvert geopolitics”

“Rauschenberg developed a practice of ‘improvisation’ with found materials that was borne out of his work with [Merce] Cunningham and John Cage,” Wood explains. “He applied the same aleatory principles they were experimenting with at Black Mountain to how he utilized found objects. Not just using the things he found—the umbrellas, mattress springs, clocks—as material for collage but following their ‘implications’ to set them in motion. Sometimes literally, with a working fan or lightbulb embedded in the canvas.”

Wood says that Rauschenberg’s fascination with the skills of the artisans he met in other countries also led him to purchase their handicrafts and incorporate them into his own work. “He used copper from Chile, fabric from Jakarta, ceramics and paper from China, and Japan,” adds José Castañal, a Paris-based director of Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, which represents the artist’s foundation. “Through his trips he started using all these crafts that are now so acceptable in the mainstream.”

Rauschenberg’s critics at the time accused the artist of cultural aggrandisement, a Neo-Dada turned neo-imperialist. His appropriation of local cultures is no less problematic today. But others recognised the US artist’s generosity and the spirit of altruism of the project. The alternative could have been a straightforward retrospective to burnish brand Rauschenberg. “The spirit of the endeavour, mobilising art as a vehicle for peace and mutual understanding,” is more inspirational than ever, White says. “Rauschenberg used the form of the exhibition as a means to infiltrate and subvert geopolitics.”

As the sustainability of big touring exhibitions and biennials looks increasingly problematic post-pandemic, some curators are looking to commission new works through residencies and research projects rather than ship existing pieces around the world. Simon Wallis, the director of the Hepworth Wakefield, says the emphasis of the second Yorkshire Sculpture International in 2023 will be more on commissioning new works in-situ.

Rauschenberg was a maestro of invention on a tight deadline and budget. He famously came to the rescue of the Trisha Brown Company in Naples in 1987. When a set by the artist Nancy Graves did not arrive in Italy in time, he volunteered to create one. He went to a local scrapyard, hauled back a bed frame, railings and other metal parts, before riveting them together in the theatre. After the performance the set was dismantled into individual works in his “Gluts” series. A child of the Depression, Rauschenberg’s art exemplified the ethos of “waste not want not”.

“A child of the Depression, Rauschenberg’s art exemplified the ethos of ‘waste not want not’”

The London-based artist Peter Liversidge, whose Thank You NHS installation caught the media’s attention during the peak of lockdown, reused cardboard—a favourite material of Rauschenberg—for the placards. The work was directly inspired by Allan Kaprow, who collaborated with Rauschenberg on “happenings” in the 1960s. Liversidge recalls that although as a young art student he was influenced more by “Outsider artists”, Rauschenberg was always there in the background, “a bit like the Rolling Stones”.

Like many artists who have benefited from working “on the road”, Liversidge says that being immersed in a foreign country can be liberating. He fondly recalls a residency at one of Ellsworth Kelly’s former studios in upstate New York, which was a turning point in his career. The Rauschenberg Foundation runs residencies at Captiva, to help spread its magic.

A lifelong liberal Democrat, who in 2000 made a campaign poster supporting Hillary Clinton, Rauschenberg would have been appalled by the Donald Trump presidency and his default position of blaming immigrants and foreigners, in particular China, for the USA’s problems. The artist would have delighted in defying the US President, just as he did the CIA and FBI when he pulled off ROCI Cuba despite the US blockade of the island. According to Staff, “[Rauschenberg] was probably the best artist politician since Rubens.”