Who gets to talk about periods? The answer, for the most part, seems to be no one. The notion of sanitary care is still predominantly the realm of hushed conversations and embarrassed glances, from the moment the rumblings of puberty hit the school playground, right into adulthood, when asking around for a spare tampon still fills many with dread. On the whole, the hysteria surrounding any sign of menstrual blood—particularly in the media—is still baffling. Take, for example, the fact that it wasn’t until 2017 that Bodyform took the “drastic” step to include a red substance akin to blood in its UK adverts, as opposed to the strange blue liquid that was previously deemed appropriate.

“The visualization of menstrual blood is deemed radical at best, and disgusting and vulgar at worst”

On the whole, menstruation is still deemed a dirty word. The notion of a monthly bleed is still used to societally shame women, to exclude them and to render their needs, their desires and their voices, null and void. There are religious and cultural connotations the world over that associate the cycle with being “unclean”, and the visualization of menstrual blood is, for the most part, deemed radical at best, and disgusting and vulgar at worst.

Bizarrely, my quest to consider periods within a visual arts context was brought about by Anish Kapoor’s new exhibition at Lisson Gallery in London, where an array of crimson and carmine canvases, some spattered and oozing, others painted in wide strokes, apparently reference menstruation, signifying a journey that the artist refers to in an interview with Artnet as being “in pursuit of my feminine self”. I can’t help but feel my skin crawl. An investigation of blood-like substances is nothing new to Kapoor, but this encroachment into a female domain that is so sensitive, anxiety-ridden and often derided seems both callous and ill-considered, particularly when you contemplate the contrasting censorship that women and female-identified people face when trying to visually explore the political battlefield of the body.

Take, for example, the confounding approach towards imagery by Instagram. While new modes of sanitary care might be promoted on the app (sponsored posts for new brands of menstrual cups or period-proof pants are abundant) most users will find that any blood that is in close proximity to a vagina will be censored. One case to hit the headlines involved poet and author Rupi Kaur, who found that her image of blood seeping through her leggings and onto the bedsheet was removed back in 2015. This bizarre erasure follows a stream of issues surrounding Instagram’s censorship of the natural female body, from banning images of breastfeeding mothers (the lines are still murky despite claims that nipples are allowed for the sole purpose of nursing) to realistic portrayals of body hair.

“I’m interested in women being shamed for just having functioning parts”

The relative dearth of artworks exploring periods makes sense in a culture that tends to have a homogenous and disparaging view of menstruation. Women still often face speculation that a self-assured attitude or downright anger should be mistrusted on the grounds of it being “that time of the month”, and the huge range of experiences that make up menstrual health are rarely given due consideration, from those who do not bleed for myriad reasons including age, health, contraception and gender identification, to those who have been completely crippled by conditions that take years to diagnose and treat.

The most immediate visual example of a period that springs to my mind is Judy Chicago’s Red Flag, which shows a woman pulling a bloody tampon out. It is a powerful presentation that still packs a punch, because it shows the forceful and graphic reality of wrenching this foreign object from your body, an action that familiar for so many of us, but is seldom visualized. Another work by Chicago, Menstruation Bathroom, presents a pristine white tiled room filled with period equipment and their used counterparts stuffed into a bin. The artist explains, “Under a shelf full of all the paraphernalia with which this culture ‘cleans up’ menstruation was a garbage can filled with the unmistakable marks of our animality.”

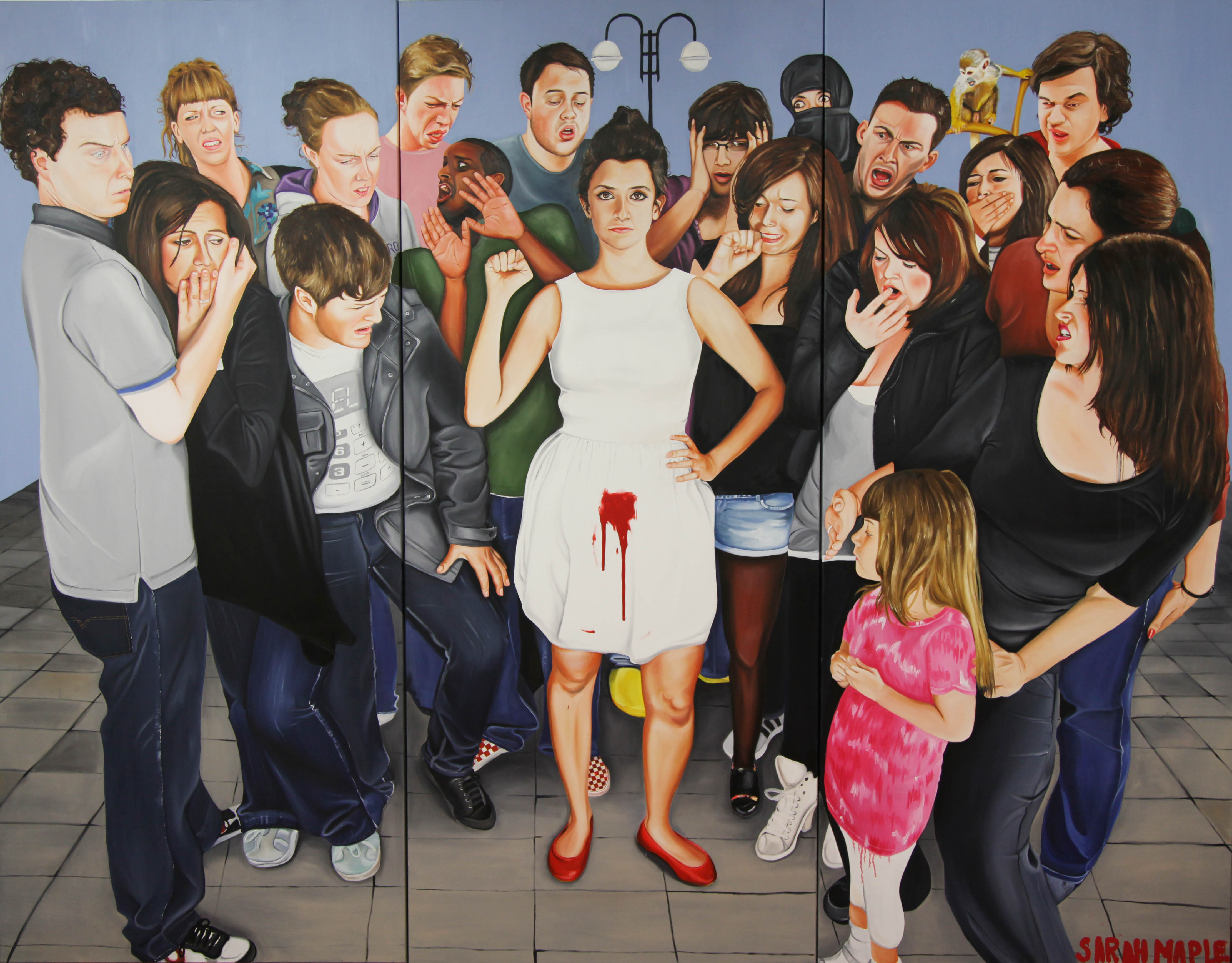

Other artists have directly referenced various unsavoury (and downright juvenile) reactions towards periods as a reason for depicting the subject. For example, Carolee Schneemann’s Blood Work Diary documented each day of a cycle in response to her partner’s revulsion at the sight of it. Likewise, Sarah Maple’s painting Menstruate with Pride presents the artist in a white dress, defiantly showing a crotch-level blood stain, while a crowd of people (men and women alike) look on in revulsion and horror. As she explained in an interview with the Guardian, “I’m interested in women being shamed for just having functioning parts.”

Similarly, Casey Jenkins made headlines for her performance Casting Off My Womb, back in 2013. The act consisted of knitting with white wool inserted into her vagina, which naturally led to some sections being dyed with her blood. Three years later, she repeated the action, but this time she included incantations of the thousands of hateful comments she got in reaction to the previous performance, which questioned everything from her hygiene to her sanity. She also programmed old knitting machines to reproduce the vitriolic statements using her menstrual wool.

Other defiant works include Sarah Levy’s portrait of Donald Trump painted with her blood, in reaction to his statement that Fox News anchor Megyn Kelly had “blood coming out of her whatever” while she was chairing a Republican debate. The furore around the artist’s choice of material is testament to how period blood is the ultimate taboo when it comes to bodily fluids and is a relatively rare example of it being used as an outright substitution for traditional mediums.

Most of the wider conversations around periods tend to point towards a lack of infrastructure or appropriate subsidies, and still suffer at the hands of apathetic governments and institutions that would rather ignore “women’s problems”. Australia was the first nation to end VAT on sanitary products at the beginning of the year, but the UK still upholds the five per cent reduced rate that is apparently mandatory for so-called “luxury items”. Concessions have been made though. Scotland began providing free sanitary products in all schools, colleges and universities last year, and Philip Hammond recently announced that they will be available in all English secondary schools, from September.

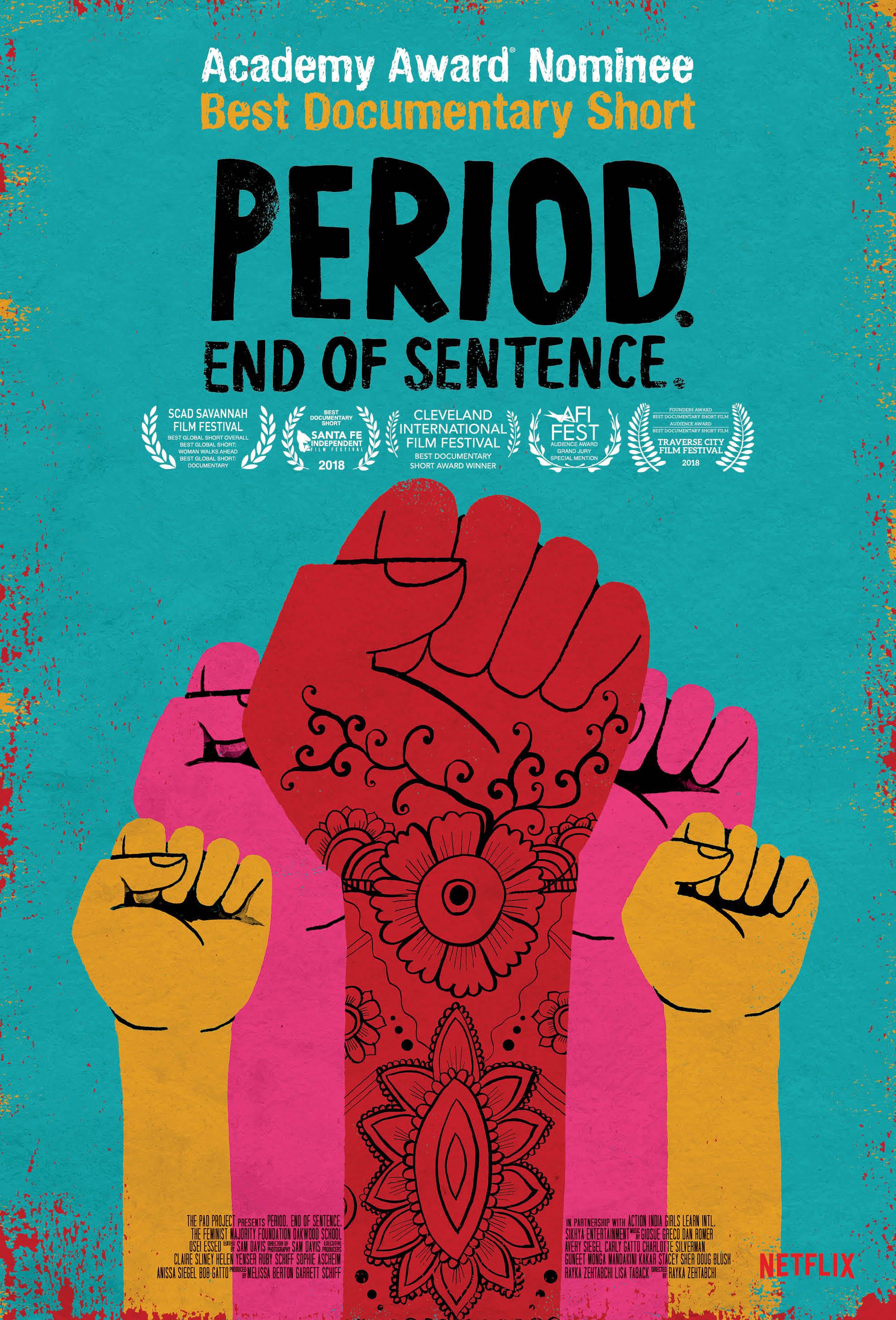

As many argue that these items are a necessity, UK charities such as Free Periods and the Red Box Project have sought to end “period poverty” in schools across the board, where pupils regularly miss class because they can’t afford appropriate menstrual products. The Oscar-winning documentary Period. End of Sentence also brought the work of The Pad Project to light, demonstrating the emancipating power of an affordable pad-making machine for developing communities (both in terms of destigmatization and microeconomies). As these kinds of initiatives begin to open up new conversations around periods, the parameters of visual culture expand too.

For example, some artists and photographers have looked to presenting periods in a less conventional way, which moves the narrative away from the somewhat clichéd images of stained pants, domestic bathroom and insufferable advertising trope of a grinning woman rock-climbing, swimming and doing pilates while bleeding. These include Megan Winstone’s recent photo series for G_IRL magazine, which includes a model visibly wearing a sanitary pad. By presenting this item in a high fashion context, it is normalized, and even a bit glamorous.

- Ottilie Landmark, Blood 7 & 11. © the artist

“We don’t talk enough about this topic which is literally part of every woman’s life in one way or another”

In a similar vein, Ottilie Landmark’s beautiful, semi-abstract images of blood collected from both her partner are somewhat ambiguous but offer visual signifiers that connect most people to the idea of menstruation. The MA fashion communication student wanted to examine the substance in its purest sense, complete with clots and varying shades: “I didn’t try to make the blood into something it wasn’t. I was mesmerized by the colour and the shapes just happened naturally as I went along. I think that it’s nice to take the period blood out of the typical context of ‘stains on underwear’ because it becomes something in itself this way. Most people think it is period blood, but I like that it poses doubt.”

She adds, “I think that we don’t talk enough about this topic which is literally part of every woman’s life in one way or another. Also, I guess I am tired of being met with the typical face of disgust from people when periods are being discussed. Instead I want to be able to speak openly about women’s health issues and fight against taboos.”

This kind of work will hopefully trigger new conversations, that will not only discuss the act of bleeding, but the entire menstrual cycle, a topic that is still woefully neglected and under resourced in medical diagnosis and discussions around mental health. Recently, on World Menstrual Hygiene Day, plenty of platforms took to discussing not only the topics surrounding appropriate period care, but the deep-rooted physical and psychological issues that come with the cycle, from the physical impact of endometriosis, to Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. At the end of the day, menstruation is about a lot more than bleeding, but tackling this visual taboo is an important and vital step in giving voice to female bodies.