It’s no great leap to assume that most photographers aim to take the perfect photo. But Aparna Aji has been on a different quest. Her aim? “To make something that was a mistake”.

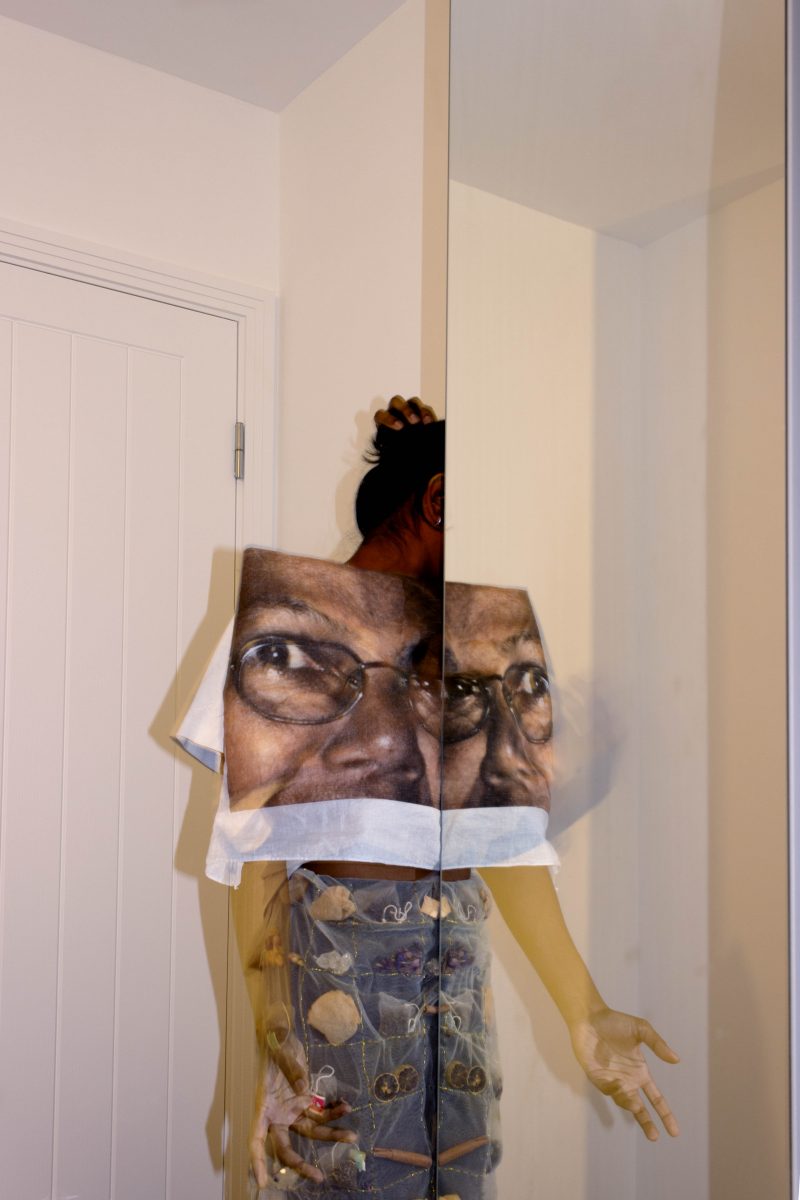

Growing up, Aji hadn’t seen images that reflected her life in India honestly and she internalised colonial perspectives of her country. The Central Saint Martins graduate was angered by the “outsider perspective” on “melanin-rich people” (she prefers this term to ‘people of colour’), as well as by age-old, stuffy rule books. So for her online series of images Three Nights Five Days Only, she “wanted to break all the rules of photography”.

“If there’s an alternate teenage me in an alternate universe, I would rather give myself these images than give her the images that were shown to me,” Aji says of her shots of India. She describes the series as “a letter to herself,” something she wishes she had when she was in conflict with her identity.

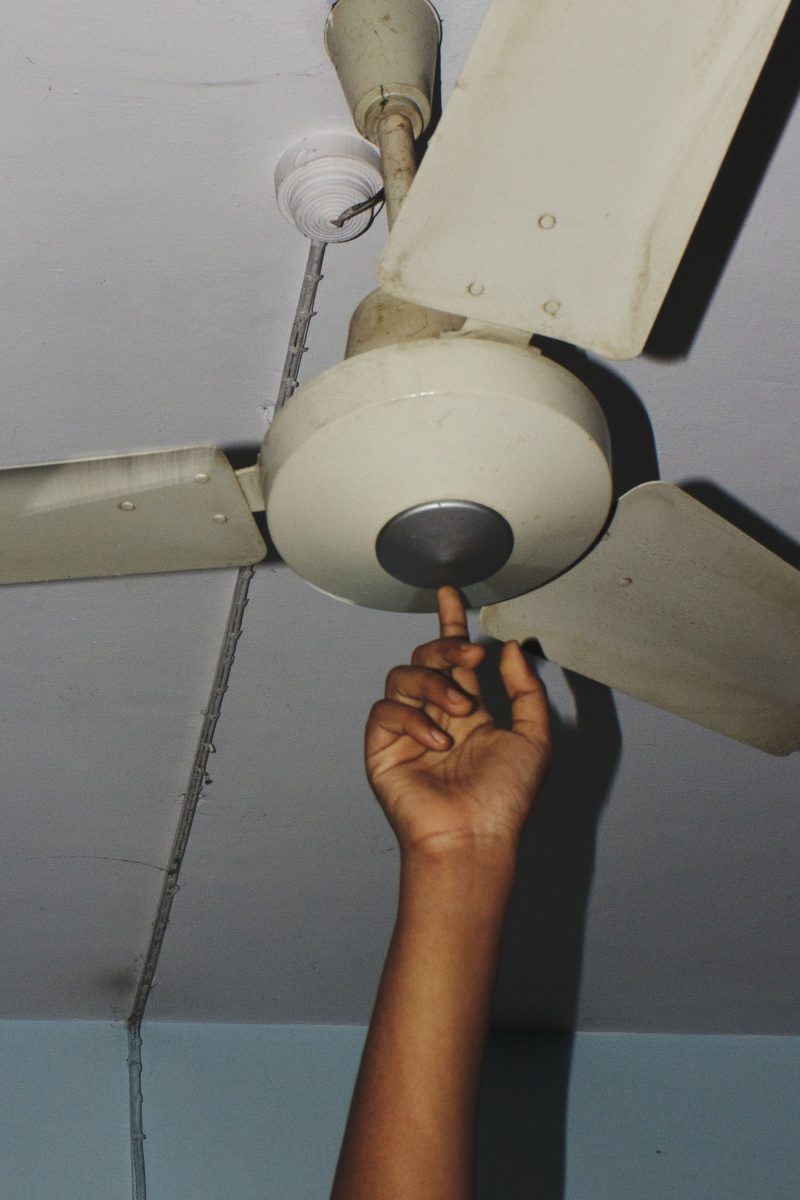

Leaving India at 18, Aji only started photography two years ago. One look at the theatrical series and it’s no surprise to hear that she has a background in styling and creative direction, and is currently working at emerging talent, fashion and music magazine Rollacoaster. This desire to capture the “little theatricalities of everyday” also stems from Aji’s fascination with vernacular photography, such as that of Erik Kessels, who makes books out of collected and found images.

“On-camera flash is a big no-no, but most of my pictures were on-camera flash… I just imagined I was my dad taking pictures of me”

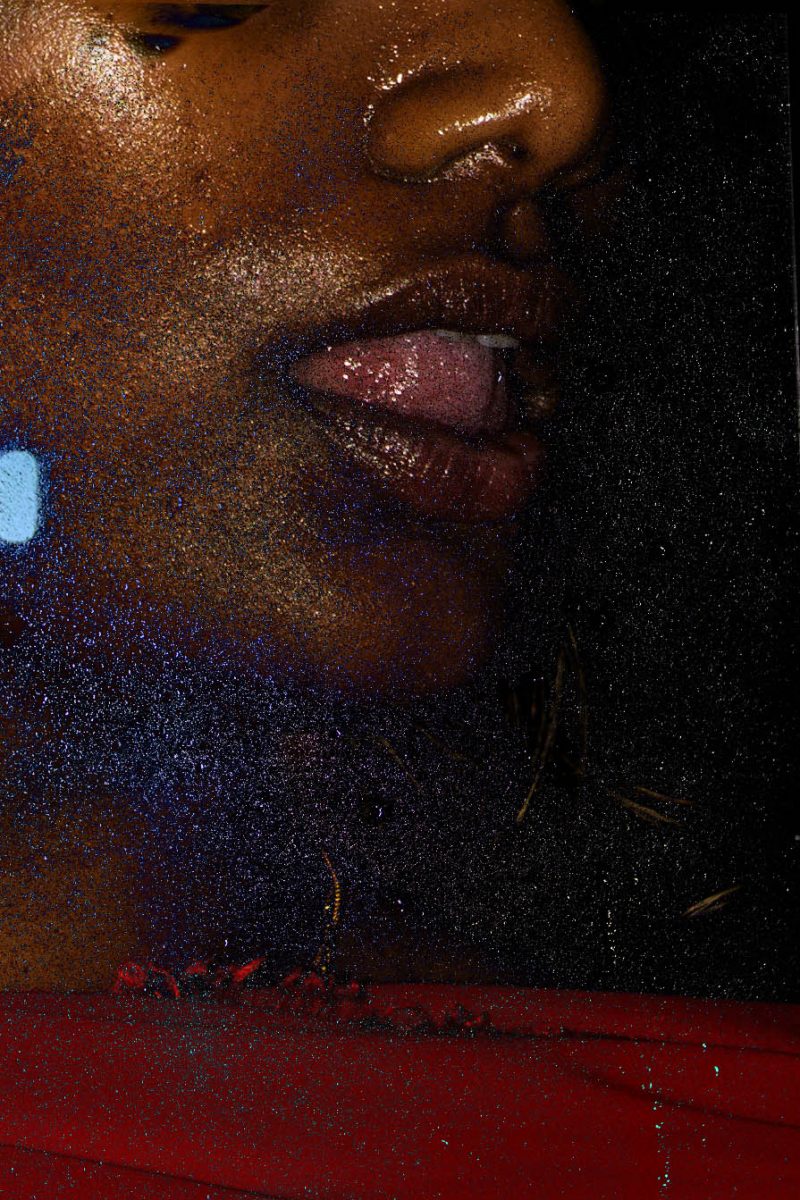

While Aji’s images shine a bright light on everyday moments that go unnoticed, something is always off, or not quite right. “I make a lot of mistakes in photography and so do my friends, and I find that really charming,” she explains. For this series, Aji admits that some “were actual mistakes, and some of them were intentional”. The beauty, though, is that you’d never be able to tell which is which.

Some images are off-focus or skewed, some have chemigrams and substances overlayed, because Aji spilled them on her scanner. She explains that “on-camera flash is a big no-no, but most of my pictures were on-camera flash,” in the same way that people take organic pictures of each other as a means of documentation. “I just imagined I was my dad taking pictures of me,” she reveals. It’s easy to see how the Instagram page @awkwardfamilyphotos also lent itself as inspiration for Aji.

“Everything about photography is colonial to me. The whole idea of image making started as a way to document us, these people in this faraway land”

Entering Aji’s world is like waking up in the midst of a fever-dream. Surreal and trippy, this series echoes the work of performance artists like Pushpamala N, whom Aji cites as a major influence for the way she challenged western ethnographic photography of India. Some of Aji’s images were staged while others were candid, an idea she borrowed from the surreal work of Sohrab Hura, as well as being conceptually inspired by the animated Japanese film, Tampopo.

“Everything about photography is colonial to me,” Aji argues. “The whole idea of image making started as a way to document us, these people in this faraway land”. As Aji rightly references, photographic ‘rules’ have been historically prescribed by western male photographers; “I’ve never seen a rule book from anywhere else,” she concludes. “It’s always a straight, white, male view on photography. That’s what I was deconstructing.”

Dalia Al-Dujaili is digital editor of AZEEMA, founder and founding editor-in-chief of The Road to Nowhere

Aparna Aji, Three Days Five Nights Only, is showing online