In a recent edition of the Spectator, resident cartoonist Nick Newman penned a cri de cœur for his profession, asking “Why does no one want to be a cartoonist any more?” The short essay addressed what he sees as the dwindling pool of new talent within cartooning—especially that of the political variety, traditionally found in Anglo-American magazines and newspapers. His reasons for this downward turn were, largely, self-evident: opportunities have narrowed; pay rates are static; digitalisation and social media are more lucrative platforms for content-sharing.

Newman also chose to include a cheap shot towards the young cartoonists to whom he was ostensibly attempting to appeal, writing that a fear of failure is deterring emerging artists from considering the profession. “Rejection is a way of life for even seasoned cartoonists,” he writes, “and today’s snowflakes can’t cope with it.” Newman then grudgingly recounts the story of a young hopeful giving up cartooning after being twice rejected from the Spectator. Perhaps he (in cartooning, it nearly always is a “he”) couldn’t find an encouraging mentor to nurture his aspirations.

“Cartooning has remained relatively unresponsive to the multiple revolutions within digital content, news and current affairs commentary“

Rather than take aim at the young, Newman might have considered why the tradition of political cartooning is so uniquely unsuited to the times we currently live in. With its reliance on caricature, accentuation and often narrow political subject matter, the form has remained relatively unresponsive to the multiple revolutions within digital content, news and current affairs commentary. Instead it clutches to tropes that have remained relatively unchanged for hundreds of years, and does little to demystify or widen the inner circles of what is a notoriously exclusive and non-diverse industry.

Newman longingly cites the twentieth-century giants of the craft: David Low, Sidney Strube and Percy Fearon. But if one is to look not backwards but forwards, it is possible to find the quality and creativity that is often mourned by traditionalists does exist within cartooning. While these mainly deviate from the mourned artistic and circulation models of the past, they are of no less value.

View this post on Instagram

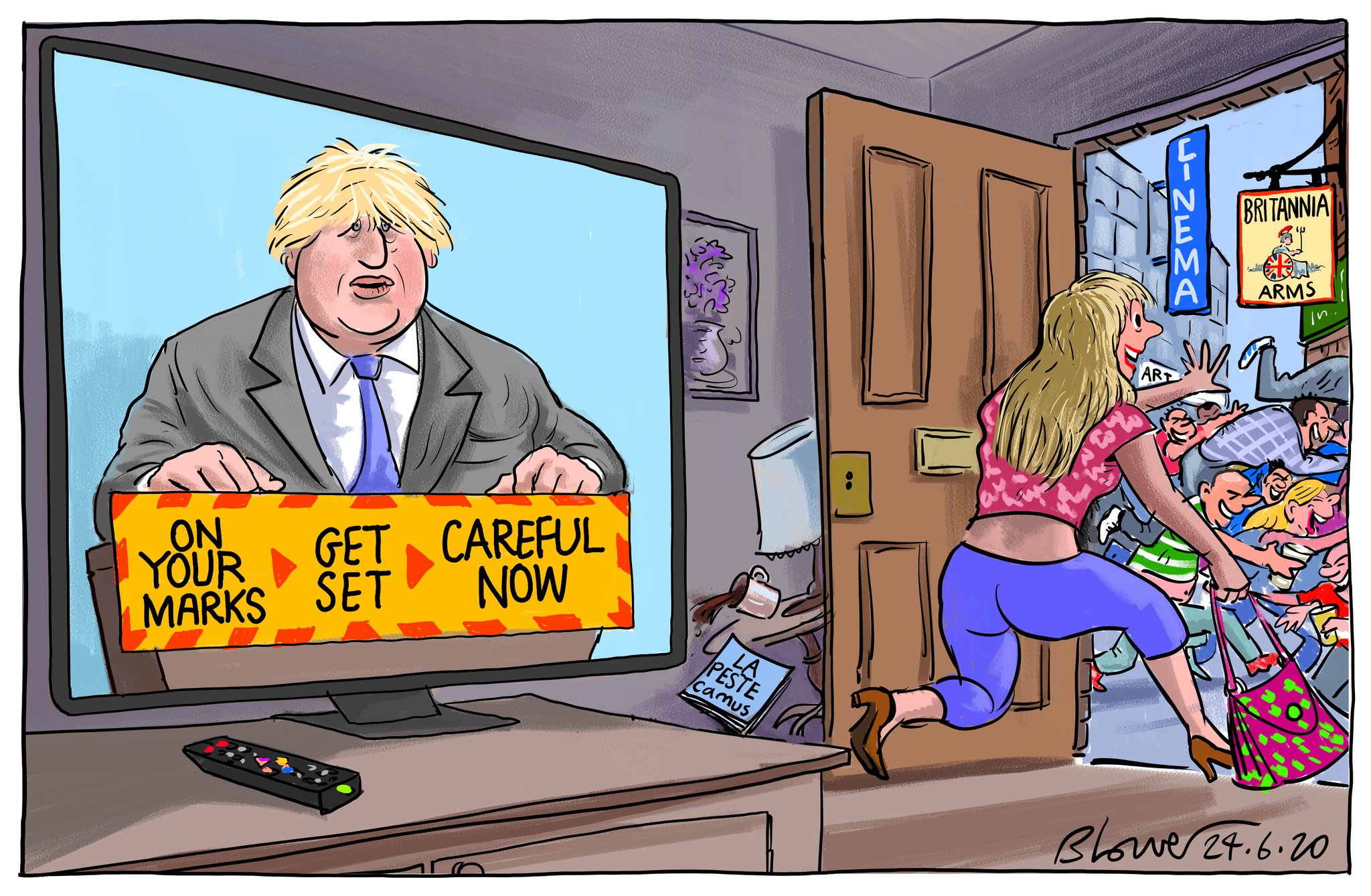

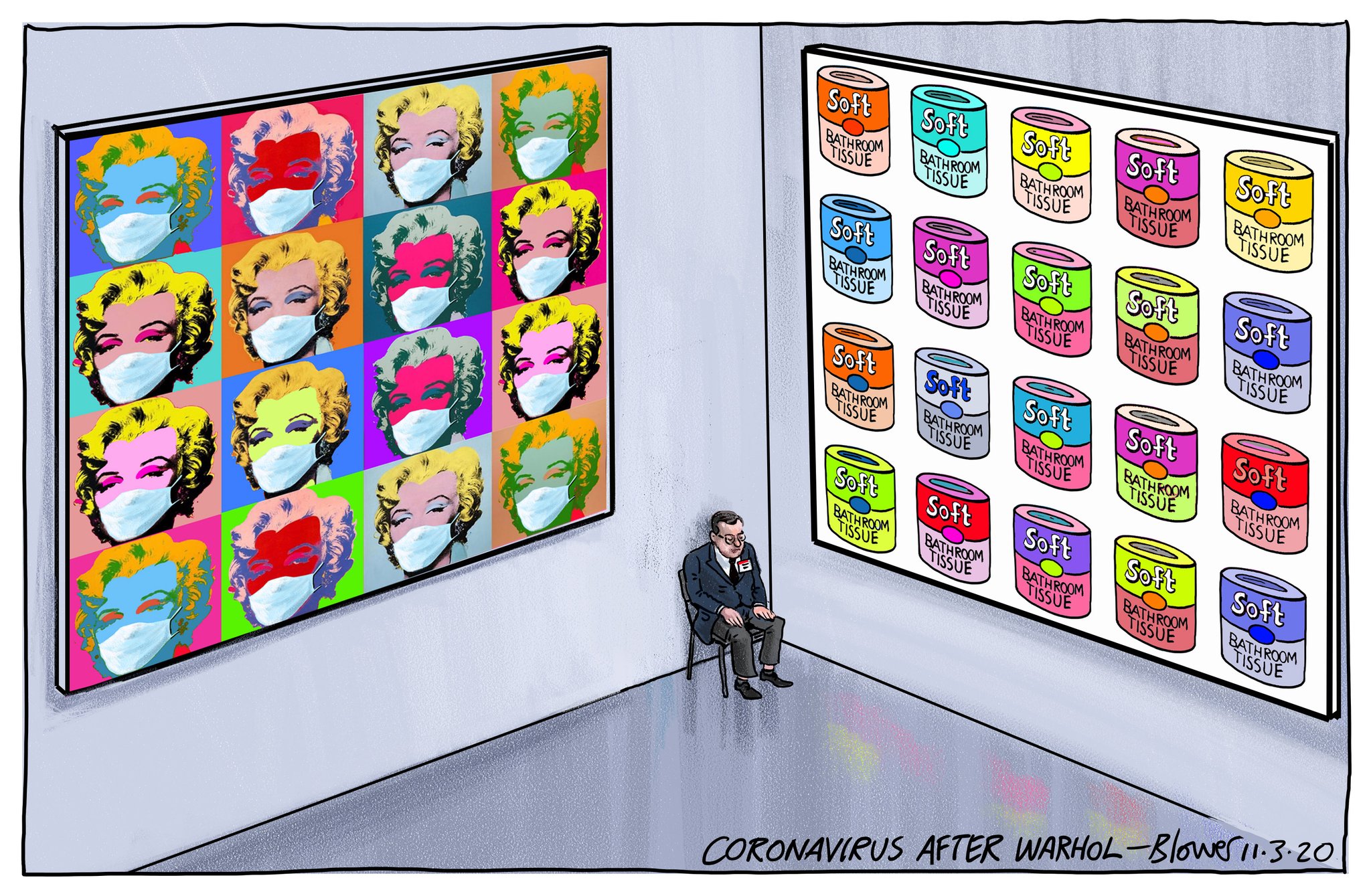

Like any other art form, political cartooning is subject to public taste, and in the face of changing times, it has the choice to either evolve or die. But unlike most other art forms, it is in the unenviable position of having risen to prominence via a now particularly unstable medium: print media. The coronavirus pandemic—which has caused several UK newspapers to record print sale drops of nearly 40 percent—has done little to help decades-long downward trends in circulation. It’s a similar story for magazines and periodicals, particularly older publications that enjoyed healthy print readerships throughout the twentieth century—though Private Eye, a key player in the UK’s cartooning landscape, is a steady and resilient outlier.

If the components of print newspapers are to be considered in terms of their suitability for digitalisation, cartoons rank somewhere close to the bottom. They may have the ability to capture a singular moment more effectively than text, but they score lowly in terms of interactive potential. Users are not interested in debating them in comment sections, and although they are often shared on social media (George Osborne, former Conservative Chancellor and editor-in-chief of the Evening Standard, is fond of his paper’s often limp efforts), they rarely go viral or convert a casual browser into a subscriber.

Contrast this with digital news stories, which are all now updated several times a day; live-blogs which are the highest trafficking items on many websites; and multimedia storytelling like video and podcasting—now heavily financed to reach new readers, sometimes at the expense of original photography and illustration. Often buried in the opinion pages alongside other digitally unfriendly formats—editorials, diary and notebook columns—cartoons are uniquely inflexible, despite their symbolic impact and biting political partiality.

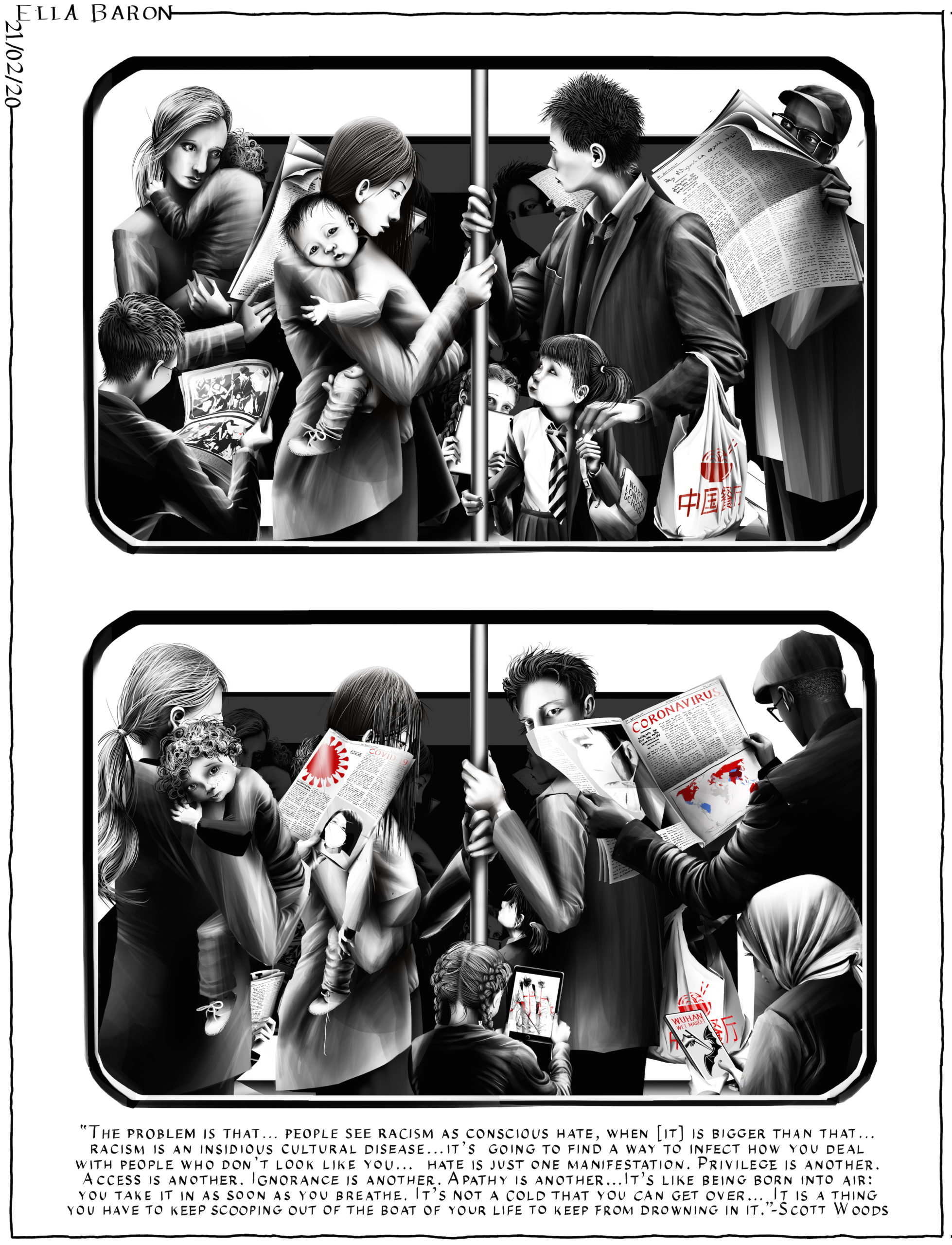

An update, if not an overhaul, of the fundamental artistic elements of cartooning could be a way to achieve the necessary cut-through to new audiences. Ella Baron, an artist at the TLS, brings a complexity to the form which is rarely seen within the broadsheet tradition. Her work often contains mystical, ethereal elements which allow her to tackle more than one subject simultaneously, and she avoids outright metaphor in favour of detail and universality. Balancing colour and black and white together, she also pairs lengthy captions or quotations to her images, breaking the golden rule of textual brevity which so defined twentieth-century cartooning. One image shows a Black woman seated in a full library, the sun beaming through a rooftop window onto her knee as she writes; a Toni Morrison quotation is pasted in capitals to her right: “I stood at the border, stood at the edge and claimed it as central…and let the rest of the world move over to where I was.” The work empowers, rather than diminishes, its subject.

“Artists are now working across a variety of media to supplement cartooning work, another reason for the supposed lack of talent in the pipelines“

Artists are also now working across a variety of media to supplement cartooning work, another reason for the supposed lack of talent in the pipelines. Henny Beaumont, whose cartoons have appeared in the Guardian and Canary, works as an illustrator, writer and graphic novelist alongside political cartooning. The age of the cartoonist on a seemingly interminable newspaper contract is well and truly over—artists are now increasingly monetising their own work through the internet and as freelancers.

One such artist is Alex Norris, a young cartoonist who uses Instagram to self-publish, and who Newman would likely consider to be a “snowflake,” for his short-lived foray into more traditional forms of cartooning. Interviewed on the BBC’s Newsnight for a feature on Newman’s essay, Norris articulated what many emerging artists are thinking: “There’s a lot more energy and excitement around a job on the internet,” he explained, citing the intimidating “old guard” of newspaper cartooning as a dissuading factor—a difficult circle to break into, even if it were a desirable place to be.

Norris was no doubt referring to a cartooning establishment which is notoriously male and white-dominated. The Guardian cartoonist Martin Rowson and several others boycotted the 2018 Political Cartoon of the Year Awards in opposition to the composition and sneering culture of the industry. In response to criticisms over a lack of diversity in the profession following the event, the organiser Tim Benson claimed that the current roster of long-serving male cartoonists “don’t employ themselves,” and that “women seem to be genuinely disinterested in political cartooning…and those who are, clearly do not have the talent or the temperament to compete with those on national newspapers.”

“Memes are able to intersect and move through various iterations for as long as they can speak to a particular phenomenon or group of people”

Commenting on Yvette Cooper’s speech on the night, Benson said that the Labour MP “ruined it at the end by virtue signalling on the subject of there not being enough female political cartoonists employed in the national press.” In a meandering blogpost on the state of cartooning, which addressed Mark Knight 2019’s image of tennis players Serena Williams and Naomi Osaka—an image widely accused of drawing on racist stereotypes—Benson bemoaned the supposed censorship of cartoonists wishing to depict non-white ethics groups, a school of thought that has grown awkwardly since the Charlie Hebdo cartoon and shooting in 2015: “If black people, or any other ethnic group, have to be treated differently from white people, is that not, in itself, a form of inverted racism?” he asked unironically. You get the idea.

A common argument about cartooning, and political comedy in general, is that the times we live in are too remarkable, or too absurd, to be satirised. This is a simplification. The reality is that the rules of signification have altered to suit the digital era. Consider internet memes: most rely on their amendability to stay relevant for long periods of time. Unlike cartoons, they are not a succession of discrete gags by a chosen individual but a snapshot of several jokes, trends or formats. Memes are able to intersect and move through various iterations for as long as they can speak to a particular phenomenon or group of people.

Political cartoons, in their traditional form, are static; their urgency diminishes over the 24 hour period until they become yesterday’s news. This is the reality that Newman misses. The future of cartooning lies in an update to the form, more open networks within the industry, and a greater embrace of the internet as a commercial and artistic tool. The answer is not further lamentation.